Back to selection

Back to selection

“No One Knows How Much Work Went Into Getting It Right”: Editor Neil Meiklejohn on Wild Wild Country

Wild Wild Country

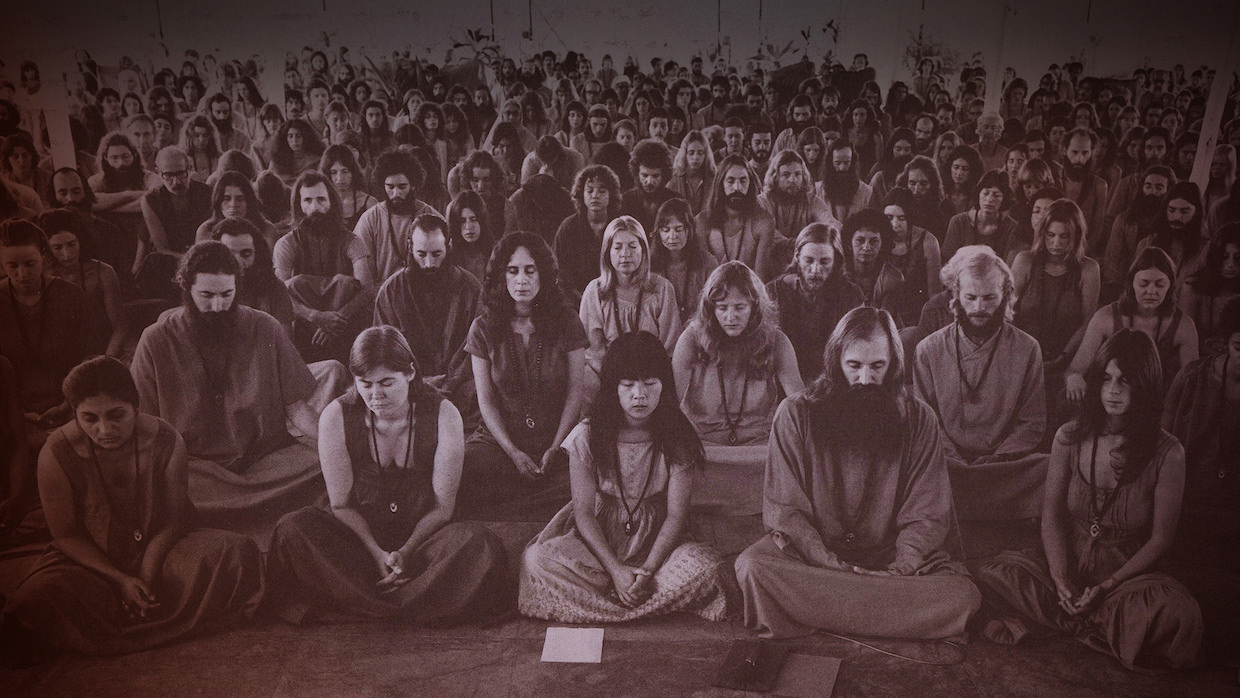

Wild Wild Country Led by one Rajneesh (also known as Bhogwan), a group of Indian believers arrived in 1981 at Wasco County, Oregon. The tensions between the new arrivals and the locals, leading (among other things) to the largest biochemical poisoning in US history on 1984, are examined and fleshed-out in the six-part Netflix series Wild Wild Country. Editor Neil Meiklejohn discussed his latest collaboration with Chapman and Maclain Way prior to Wild Wild West‘s premiere at Sundance.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the editor of this series? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Meiklejohn: I have edited and collaborated with the directors, Chapman and Maclain Way, on many of their projects, so working together on Wild Wild Country was a natural fit. I met Chapman and Maclain when they were working on their first documentary feature film, The Battered Bastards of Baseball. They needed editing help to get their film ready for Sundance and they reached out to me. From the moment we met, we just clicked.

I think it is our personalities; we appreciate each other’s sense of humor. Chapman and Maclain are both incredibly generous, thoughtful and have impeccable taste. In the bay, I saw their tireless work ethic and dedication to creativity. As a team, I think our greatest strength was that we always wanted every scene to be the best it could be and we always had a ton of fun getting it to that place. You need to have that chemistry to spend hundreds of hours together in a dark bay and the filmmaking process is always best among friends.

Filmmaker: In terms of advancing your project from its earliest assembly to your final cut, what were your goals as an editor? What elements did you want to enhance, or preserve, or tease out or totally reshape?

Meiklejohn: From the beginning, I wanted the audience to feel like it was on the ground, or sitting on the shoulder of one of our characters during that time. I wanted Wild Wild Country not to be a look back into history, but a re-living of it. The audience gets to experience the magic of the ranch and feel the excitement of seeing the Bhagwan for the first time and the dread of the farmer watching hundreds of his new red-clad neighbors driving through town.

I also wanted to convey the grandness of how these ordinary people were confronted by extraordinary situations. Our characters are transformed from the moment of getting off the plane from India or tending to their ranch in central Oregon, and then suddenly being on the national news. I wanted to convey not only the steps it took to get there, but also how quickly all the characters’ lives changed and their worlds spun out of control. I wanted the audience to experience what this was like, to feel their excitement or confusion, and walk in their shoes.

To illustrate that experience I was also careful to include intimate moments from the archival footage as well. For example, while the attorneys are battling it out in front of the news cameras, off to the side there is a guy trying to make a buck selling Bhagwan t-shirts in front of the court house. Both are equally important in the overall feeling of what it was like to be there. I combed through the footage with a magnifying glass to help find these smaller but equally special moments in time to create the experience of being there.

It was also important to show that for many people living on the ranch, this was the greatest time in their life, living in utopia. I think the series has a bit of a Guillermo del Toro-esque sentiment to it: a fantasy world with all of these rising tensions and collisions surrounding it. As the editor, I wanted to make sure the magic of the ranch did not get lost in the conflict.

Our team also decided early that Wild Wild Country was not going to pick sides but rather show the perspectives of the characters as they experienced the events surrounding Rajneeshpuram. My goal as editor was to have the audience experience what the historical time like was for our characters and let the viewers make their own decisions. For me, it was a very freeing decision not to have the “good guy” or the “bad guy,” but to focus on the experience, not some agenda.

Filmmaker: How did you achieve these goals? What types of editing techniques, or processes, or feedback screenings allowed this work to occur?

Meiklejohn: Early in the edit, I realized that each scene was really two or three scenes. What I mean is that to show everyone’s perspective, I had to establish a “point/counterpoint” or “action and reaction” style so that the viewer hears Rajneeshee perspective on an event, issue, or topic and it is followed up by the outsider (the townspeople or law) perspective. As the two or three usually saw the matter quite differently and to meet the goal of giving weight to each perspective, I treated them almost as different scenes. I used different music cues and editing styles to help illustrate the contrast in perception. As the story got bigger and bigger, and the ranch began to disintegrate, more and more voices got involved; it became a bit of a balancing act to show the many perspectives of the characters on complicated issues. This battle between our characters is really the backbone of the story and it illustrates the heart of the conflict around Rajneeshpuram, a clash of cultures.

To experience this battle in the moment, the decision was made to lean heavily on raw archival news footage so the viewer can feel the camera moving in the cameraman’s hands, and can feel the shaky chaos as the reporters run to the scene. Stylistically this worked. We had footage from multiple decades with very different looks which created a collage of different types of imagery. At the time of Rajneeshpuram the media was transitioning from film to video, I embraced the beauty of the different types of footage available and used it as a story telling technique. The passing of time could actually be seen in our footage as the film technology evolved.

Feedback was a giant part of the process, Chapman, Maclain and I were constantly sharing with our executive producers and Netflix to get feedback and see what was working and what was not. On a story as big as Rajneeshpuram that involves a tremendous amount of research and deals with intense socio-political issues, outside perspective is needed to just ensure clarity.

Filmmaker: As an editor, how did you come up in the business, and what influences have affected your work?

Meiklejohn: After graduating from the University of Colorado Film School, I moved to Los Angeles to work at Rock Paper Scissors as a production assistant — running tapes around town, picking up dry cleaning, all the usual P.A. tasks. It was my first post college job and I have worked my way to editor at the company. It has been a great experience; I have had the opportunity to work with and be mentored by the best. Storytelling is what editors do and I have been exposed to the entire gauntlet of filmmaking, from feature films and TV to commercials and music videos. On every project you learn something and hone your craft, I think being able to work in so many mediums has allowed me to meld all of these different worlds into my editing. On a project like Wild Wild Country, you have to craft a story out of hundreds of hours of archival and interview footage, and the experiences I have gained from working in all of these other mediums has helped me.

Filmmaker: What editing system did you use, and why?

Meiklejohn: I work on Adobe Premiere Pro, the editing system that I have fallen in love with and what I use on all of my projects. For Wild Wild Country, with archival footage from many sources and formats, a system was needed that could handle all the formats allowing us to work quickly and focus on the creative not the technical.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to cut and why? And how did you do it?

Meiklejohn: I think the most difficult scenes were the legal battles because they required the most explanation. They are delicate scenes because they are so important to the story but can easily get wordy and boring. In episode one, the Government and a land use watch-dog organization bring a case against Rajneeshpuram, arguing that their city violates land use laws and needs to be torn down. It is early in the series and is the catalyst for the legal conflicts against Rajneeshpuram. The Rajneeshees were in danger of losing their City. This scene had to be right to show how this would be devastating to Rajneeshpuram and to illustrate how Oregonians were putting this much pressure on the Rajneeshees. It is a pivotal scene in understanding the chaos that follows. Many of the interviews and much of the archival were heavy on legal jargon, so it took a lot of work to bring out the emotional impact. In retrospect, it is a small scene but no one knows how much work went into getting it right.

Filmmaker: What role did VFX work, or compositing, or other post-production techniques play in terms of the final edit?

Meiklejohn: Wild Wild Country had very little VFX but Method helped with some graphic scenes and they did our titles. We had a few After Effects-type scenes where we fly through graphics, pictures and documents to give a unique feel to the scenes and to provide a lot of information quickly.

Filmmaker: Finally, now that the process is over, what new meanings has the series taken on for you? What did you discover in the footage that you might not have seen initially, and how does your final understanding of the series differ from the understanding that you began with?

Meiklejohn: I think the biggest take away is how much the story is still relevant today. The issues surrounding Rajneeshpuram (immigration, freedom of religion, land use, and cultural differences) are major issues in our news today. The Rajneeshpuram story is an American story and asks the viewer to take a serious look at the foundation of this country. I am also surprised how much I do feel for each character. On one hand, Rajneeshpuram seems like a ’80s Burning Man or an adult summer camp I would have loved to visit. On the other hand, I clearly understand the citizens of Antelope and the shock to these retired people who were completely invaded by a cult. Not everything is black and white and there really are two sides to every story.