Back to selection

Back to selection

“We Process Our Memories In a Dreamstate, Building Meaning Between the Absences”: Samara Grace Chadwick on her Hot Docs Doc, 1999

1999

1999 1999 is one of the most haunting documentaries I’ve ever seen, which perfectly suits its subject matter. Director Samara Grace Chadwick returns to the small Acadian town in New Brunswick, Canada that she left as a teenager after a wave of suicides shook her high school over a handful of years, though the actual events always remain somewhat mysterious and opaque. A portrait of a group of people who, just when they were beginning to live, came intimately face-to-face with the finality of death, 1999 is not an investigation but an immersion into the emotional flux of a community struggling to cope with loss and a period of time when the unimaginable became a regular occurance. Chadwick is too smart and subtle a filmmaker to simply invite her subjects to recount traumatic episodes or to try to excavate the past for journalistic truth. Instead, the movie immerses you in a very particular milieu and moment in time= and by doing so sheds light on universal emotions and a period of life that all of us who are fortunate enough to make it to adulthood can relate to. Deceptively simple and associative, 1999 is a philosophical mediation on memory, sorrow, uncertainty, adolescence, and rebellion.

1999 was produced by Parabola Films, Beauvoir Films and the National Film Board of Canada and was an official selection of Visions du Réel. It plays Hot Docs this weekend.

Filmmaker: You made a film that could be described in a very sensationalistic way, but there’s nothing sensational about it. It never becomes become maudlin.

Chadwick: Yeah, thank you! I think one of the first notes I took when I began the project was “it’s a film about suicide that is not a film about suicide.” It was clear from the very start that there were absences inherent to the film: the voices and perspectives we would never know, and absences that were traced around my own instinctive aversion to describing the way these kids died. While filming, I spent three winters living in Moncton at my dad’s, and it became evident that in addition to those absences, there would be a constant tension between what remains and what is erased: what is gone, what is forgotten, what is deliberately abandoned, what is too horrific to name. I was curious to build a film around these very blatant holes, and yet to weave subtleties around them. It was an interesting starting point because ultimately I feel that this is a film about language and memory, and memory works in a really interesting, and somewhat similar way: we process our memories in a dreamstate, literally, building meaning between the absences. Maybe that’s why the film kind of feels like a dream?

Filmmaker: Yes, it’s totally a film about memory, first and foremost. That’s how I described it afterwards to a friend.

Chadwick: When I began 1999, I was finishing my dissertation, and was coming from ten years steeped in academia. So my original writings about and approach to the film were really theoretical. Thank goodness, I ultimately got rid of all of that heavy theory though the one core idea I retained was my interest in how the brain physically, biologically, registers memory. How trauma exists physically in the brain and in the body. I’m fascinated by how, by remembering, we inscribe physical pathways in the brain, pathways that divert us from other possible memories. From what I understand of neuroscience, neural pathways are transformed by how frequently they are used — and we all seem to have a tendency to trudge through a certain memories, certain pathways, at the expense of all the other possible interpretations of that story.

Filmmaker: And we dig those ruts deeper every time we go back to it.

Chadwick: Exactly! We all know the cliché, “The most pure memory is the one that you never remember.” Or the one that you’re remembering for the first time, which was also part of my process: how to get people to a state where they were in a stream of consciousness, returning to a space of intact memories. Remembering for the first time. And then there was also this idea that by remembering in a space of trust and comfort, in acknowledging trauma, we could almost flood the brain with endorphins, and raise us up from these really downtrodden, heavily worn down ways of talking about things, and actually allow for more subtle, scintillating, compassionate way of telling our own stories.

Filmmaker: Which is why it’s not so much that you interviewed people, but rather that you’re in conversation — or you’re even setting up conversation between others — so there’s that spark where you trigger each other’s memories, or have things that you’ve forgotten come back in a flash.

Chadwick: The film centers around these stories that we began telling ourselves about ourselves at age 14 or 15, and how we continued to do so until our mid 30s.There’s this revelation, in some subtle way, that we’ve become certain adults as a result.

Filmmaker: There are so many obvious things that are not said. You never tell us how the kids killed themselves, you don’t tell us how many. It sort of puts the viewer in a bit of a fog.

Chadwick: The way I thought about this was inspired by a little word that I really like, the word “obscene.” And the way these kids died was obscene. But obscene also in the original sense of the word which is “off stage.” So, you know, in Greek dramas the really violent things — like someone getting their eyes gouged out would happen “obscene” because they were too hard to stage. But the act of removing a scene from sight allows everyone to almost collaborate with their imaginaries… It’s almost like language, it’s like the opposite of the naming and the material, it’s allowing things to linger in an imaginary space, one in which everyone has a personal interpretation, one that is deeply stirring, emotional, unknowable.

The imaginary is important too because, none of us saw — we all have images of these people and how they died — but none of us saw. But we’ve thought about them so much that there is an imaginary, there are actual physical memories. Lots of people recounted very vivid recurring dreams.

The other absences we worked around in the edit were often the moments where people are either super expository, or when they cry on camera. The moments when the really explicit thing is said: “This is how this person died,” “this is me crying because of the betrayal I felt.” In my experience, many films isolate these moments with the sense that, “this is where the magic happens, this is where the thing is said.” Or to use horrible industry language “where the blood is shown.” But Terra [Long], the editor, and I came to the realisation that when the thing that is said is exactly what is said, there’s nothing more in that scene than those words and the weight of them. Again, it’s like tracing the contours of the thing without falling into it.

Filmmaker: So there’s also something obscene about being so direct. But it’s also kind of predictable. Last time we spoke you called this the “banana/banana theory of editing.” Someone says banana, and you show a banana.

Chadwick: Yes, banana/banana is a person saying “I was so sad.” And then they cry. We sought instead to convey that they were sad and that they were traumatized without really seeing them cry or ever having them say, “I was traumatized.” Instead, Terra picked up on the moments when their lips quiver, when they swallow down a thought, when their eyes show they are elsewhere in thought. She has a deep intuition for finding the moments information is hinted at — and you know it, as a viewer, because you have that human intuition too! Viewers have that capacity, without information being shoved at them. It’s actually a lot more effective and beautiful I think, because the information is contained within the moment without being said. It invites affection from the viewer instead of prescribing it outright.

Filmmaker: The film takes you back to being a teenager, when your world is your high school, it’s not your job to figure everything out, things are happening to you that are bigger and beyond your control. And, that’s part of why, while it’s not exactly lighthearted, the film does have a levity.

Chadwick: This is one of the main very hardcore surgeries we did in the edit — half of the interviews in the rushes were with what we called adults, which are the people who were adult in 1999. During early rough-cut screenings, as soon as one of these adults came on to the screen they carried a certain authority that completely deflated the magical adolescent liminality present in the interviews with the kids, the people my age. It was like the two generations could not coexist. When they were presented together, both of them became banal. The adults became too dogmatic and rigid in their attempts to decipher — they almost had too many words. And then the kids also became, in contrast, too naïve, and the enchantment of their experience was compromised. And so, we cut all the adults out.

Filmmaker: It’s so funny because these “kids” are people in their mid 30’s. They’re not kids, but you have them returning to that state of mind.

Chadwick: One of the guidelines that I set for myself was, “We’ll never know more than what I and the other people in the film knew at the time.” There’s nothing more, there’s no more information revealed than our experience. I could make the film through my own perspective and that felt like the only responsible way to make this film is to not in any way purport to knowing more than I knew, or to offering any supposed objectivity. I hadn’t originally planned to be in the film, but it felt like the only respectful way to do it was to acknowledge that it was —

Filmmaker: Yours.

Chadwick: Completely limited by me. That I could never extend beyond my own knowledge and my own — my vantage point…

Filmmaker: At one point one of your friend in the film makes a very provocative comment that you don’t answer. She says, “What’s the point of remembering?”

Chadwick: Trauma is a blockage in so many ways — it’s like the cliff where language drops off. We don’t know how to talk about it, we don’t know how to talk to one another, it’s where the memories get buried, it’s where people stop being able to connect with one another, it’s isolation. And suicide is like the ultimate blockage, it’s the drop off into nothing. I see the act of remembering as flow, it’s like bringing oxygen back into the spaces that have gotten compacted and heavy or bringing shape, scale to feelings that are a total abyss.

Filmmaker: In the film you leave that question hanging provocatively, you do not answer it.

Chadwick: That’s just my answer, and I think everyone else has a different answer. But I think viewers might leave the film with the answer in the sense that it’s an invitation to remember certain experiences still lingering within them, especially teenage things, because the film really does somehow takes people of all ages back to high school.

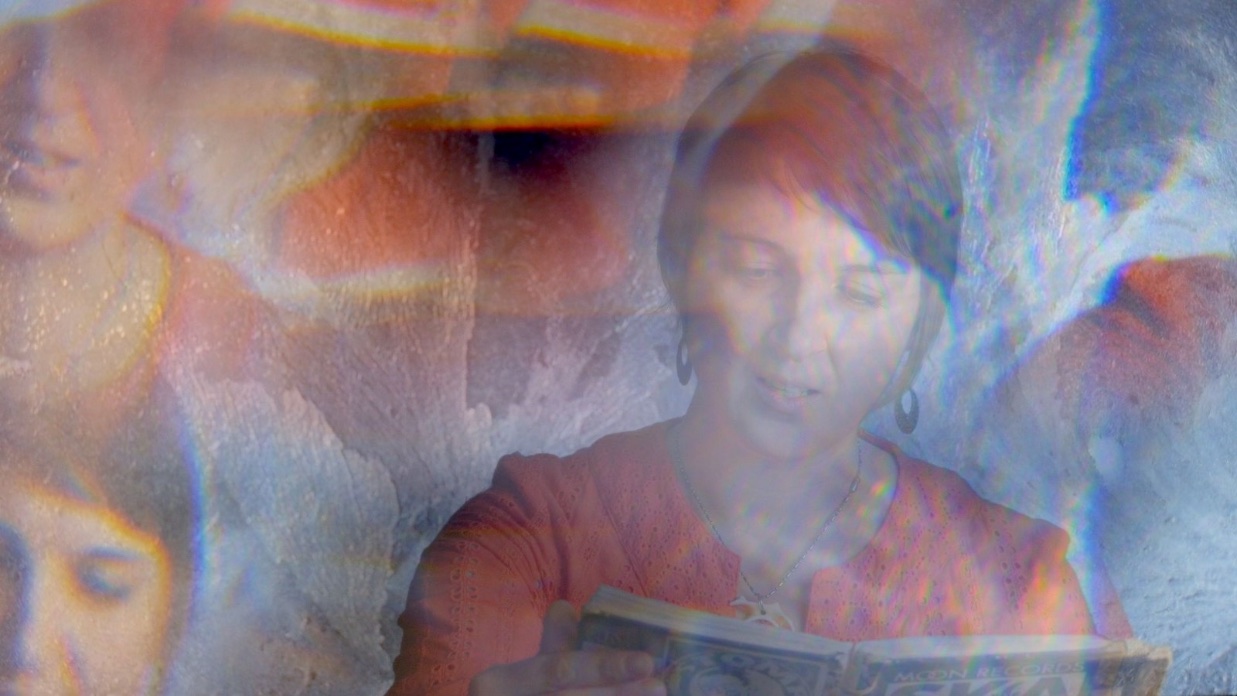

Filmmaker: Moving from content to form, let’s talk about the aesthetic. The film is dreamy without being overdone, and nostalgic without being cheesily retro. At some points you film through a prism, which produces an interesting visual effect.

Chadwick: My sister found that prism in our dad’s barn as we were going through our boxes, and we shot a lot of the prism stuff right then and there. And the prism became such a beautiful useful visual symbol, of the ghosts, of the tears, of the many ways a specific event can exist in people’s lives. It brought light into the story, and also fragmentation of the image was such a simple way of intertwining form and content — of showing how everyone held only partial images, partial stories, a colour on a spectrum.

Filmmaker: Nobody has the whole picture.

Chadwick: And that together, combined, something can emerge, something that is collaborative, but that everyone just has a tiny piece. The collaborative element manifests as transparency in my mind, like images flowing into one another, allowing us to see differently. I saw it as a chorus really — of images and voices.

Filmmaker: Can you say more about the Acadian element? The subjects, and you, come from a place and speak a language that’s not exactly well known.

Chadwick: I feel like the film has deep politics within it, and in a gentle, playful way, that politics is manifest in the way we talk, in the actual politics of the space. Acadians use a strange hybrid language, Chiac, which is a combination of the French spoken by the fisherman and farmers that first settled the land, and the popular culture of today, which is deeply seeped in English. It is an unusual, translucent language, that requires a certain mastery of both English and French, as well as a certain playfulness to then subvert them both. In the film it was interesting from the outset to get people to speak Chiac, because as soon as a camera comes on, we all have a tendency to perform this correct version of how we were taught to speak French in school. As soon as you realize that there is going to be a broadcast outside of the original moment, there is an impulse subconsciously to put on this mask of formality. And in correct French, people also have a different relationship to their own stories and they express themselves very differently.

Filmmaker: It’s like a code switching.

Chadwick: Yeah it’s a code switching, and it’s a — you know I think we often inhabit different personalities for different people, and people who are multilingual also have different personalities with different languages. But there’s something that is very sincere in the way Acadians speak — something that I deeply admire, which is a little anarchistic, or fluid. There is a joy and an exuberance in their ability to transcend the binary of the politics around speaking French in Canada.

Filmmaker: At the end of the film there’s this phrase that someone says that has a double meaning, something like, “I took my life into my own hands.”

Chadwick: In French she says “When you take your life, you take control,” and I guess it’s unclear exactly what she’s saying.

Filmmaker: But she’s saying it in this way: I took my life to really live, I took my life into my own hands — it’s kids who quit school or just decided to go their own path, which embodies the anarchist spirit you mentioned. It implies that there’s this other way…

Chadwick: Of taking your life.

Filmmaker: Of taking your life. By the end — I won’t give away what the kids do — it almost feels like there’s this existential choice, people can die or rebel.

Chadwick: And I think that that’s, that was exactly how we intended that phrase to land. Adolescence really is this cusp between childhood and adulthood, the moment you realise the choice between life and death. The year 1999 was also a cusp, of the millenium, the year of Columbine, Y2K. I distinctly remember a general subliminal dread of the future.

Filmmaker: That’s really interesting. 1999 was also pre-911, pre-social media. It was a kind of turning point as you say. But I think it’s good you don’t mention all of that directly. You leave matters much more open instead of imposing meaning on what transpired.

Chadwick: Exactly. Yeah the affection in the film is also towards the viewer and towards the viewer’s own experience. It was imperative to offer this viewer the ability to have agency in how they want to interface with the film. I see less and less films that grant much agency to their audience, as though there’s a lot of distrust in the audience’s intelligence, perhaps because it extends beyond the predictable, and beyond the language of metrics and impact. And yet my personal understanding of the word my politics is that it can only truly exist if we trust people’s intelligence, we can we cannot channel their capacity for thought into predetermined, prescribed spaces.

The many processes of this film helped me to let go of my own expectations and vanity, to be humbled by the project. Making the film really felt like a heart opening experience — and I think it was for all of us. And as the world right now does its best, it seems, to close our hearts, it feels a little punk, like a little wink of teenage rebelliousness, to reignite our capacity for affection.