Back to selection

Back to selection

Don Hahn Talks Howard Ashman, Musical Animation, and his Documentary Howard

Howard

Howard For a few brief shining years Howard Ashman was one of the most influential filmmakers in Hollywood. With the composer Alan Menken he had already created an Off-Broadway hit with Little Shop of Horrors, and, at Walt Disney Animation Studios in the late 1980s, he was a pivotal force in creating The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin—films that galvanized an industry-wide animation renaissance—as not just a lyricist but a producer, writer, and director. He died of AIDS-related complications in 1991, however, while the latter two of these films were still in production: Beauty and the Beast was dedicated “to our friend Howard, who gave a mermaid her voice and a beast his soul.”

One of these friends was Don Hahn, a producer on Beauty and the Beast and then a series of other Disney films: The Lion King, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, The Emperor’s New Groove and Atlantis. He’s also helped oversee numerous short cartoons, produced or executive produced live action films like Maleficent and Beauty and the Beast, worked as an executive producer of the Disneynature studio that produces the studio’s wildlife documentaries, run his own production company Stone Circle Pictures, and directed three feature documentaries: Waking Sleeping Beauty, about the Disney renaissance of the late ’80s, Hand Held, about photojournalist Mike Carroll and his work documenting the pediatric AIDS crisis of Eastern Europe, and now Howard, an archival documentary about Howard Ashman that premiered earlier this year at the Tribeca Film Festival.

On a personal level I was excited to see a documentary about Ashman. I learned about him a few months after his death: his films at Disney were my entrée into the world of cinema, and I quickly soaked up everything I could about these animated films and his work on them. Perhaps even more importantly, before that point I was only aware of rumors and disgust about gay men and the AIDS epidemic, and Howard Ashman was the first victim of the disease—and even the first gay man—whose name I knew. And the fact that he created such beautiful songs and beautiful films penetrated my consciousness about LGBTQ issues and began a long journey in my personal beliefs regarding homosexuality. As Hahn told me in our conversation, Ashman was not a political performer, but I believe his work brought light to millions of people that transcends the words that he wrote. Howard is a fitting tribute: a film that relies entirely on archival material to show that personality up close, giving the public the best insight we’ve yet had into Howard Ashman’s creative process.

Filmmaker: Howard seems like a combination of your previous documentary work, with the Disney renaissance in Waking Sleeping Beauty and the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Hand Held. Since you’ve already filmed and written so much about Disney animation in the 1980s and ’90s, what made you want to create a film about Howard Ashman specifically?

Hahn: Waking Sleeping Beauty is really a story about a renaissance in animation and the executives and circumstances that made it happen. Howard was just one component, one very special component in that story. That film was nine years ago and I had always felt like the full story of Howard Ashman hadn’t been told. There’s no book, no autobiography and, save for a few blog posts and articles, I was afraid his story was getting lost. I also felt like we’re in the middle of a golden age of documentary and 27 years after Howard’s passing was enough time to pull together his story and tell it completely. Howard is in the style of Waking Sleeping Beauty, because that’s my style for telling the two stories. It’s pointless to have on-camera talking heads of old people reminiscing when we had such brilliant clips and recordings of Howard telling his own story. If this was a story about one of the greatest storytellers of the twentieth century, why not have him tell his own story, supported by those who knew him and worked with him?

Filmmaker: Of course this is a personal subject for you and everyone who worked with him. What was it like going back all these years later and revisiting Howard’s life and achievements?

Hahn: When you work with someone you don’t really learn about who they are, except on a superficial level. When you tell their story in a film, you need to know them like a brother. We started going through Howard’s papers, lyrics, scripts and correspondence in the Library of Congress, where his papers are archived. Yes, he was a friend and collaborator, but more than that he was a really interesting, curious, driven person and every piece of paper and photo that we found would bear that out. The search for media turned up things like an old answering machine tape, dozens and dozens of work tapes with Howard workshopping songs with Alan Menkin or Marvin Hamlisch. Once in a while a gift would drop down out of the sky. A reporter called us on the last week of our production and had heard we were making a film about Howard. He was at the Little Mermaid press junket in 1989 and asked if we wanted a copy of his recorded interview with Howard and Alan. We’d been looking for something from that junket for two years and had given up, and then this tape just falls out of the sky. Amazing.

Filmmaker: What was it like to work with him?

Hahn: Howard was surprisingly collaborative. He was opinionated, and always had a solution or an approach to a story problem, but he would also listen and work with the directors in a productive way. He wasn’t a diva with us. I think he really enjoyed the animation process because it is totally collaborative, and the best idea wins. Howard also had an astonishing encyclopedic knowledge of films and musical theatre references and footnotes that explained how it had worked in other shows, and how it would work in this one. The last thing that is hard to get across completely in a documentary is how funny Howard was. You see it in his lyrics and writing, but just in the room and in the moment he was so fast and funny in story meetings. It was exciting to be in the room.

Filmmaker: You rely heavily on archival footage in these films. Obviously Howard’s life transcends the films he worked on at Disney, but are there any ways you make sure the material you’re assembling speaks to broader themes than just retelling how those movies were made?

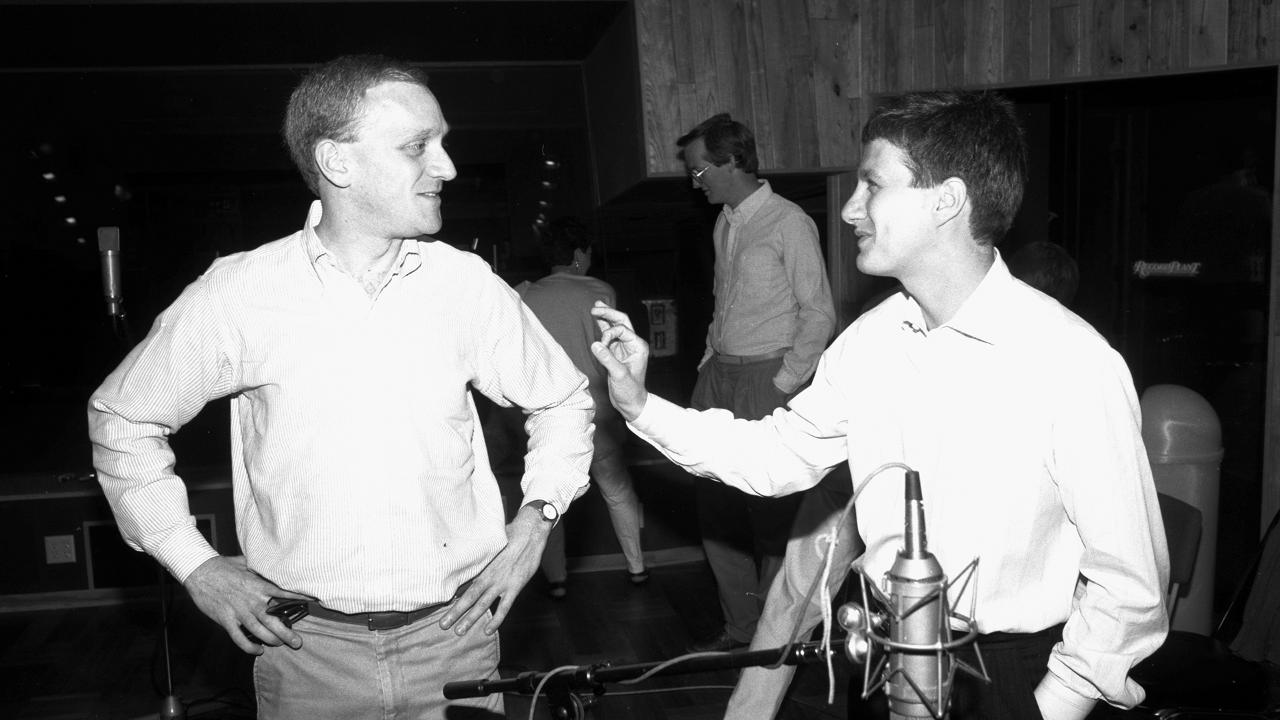

Hahn: The film is about Howard’s life, so yes, the plot has to cover the main events, people and projects that he touched, but more than that the film is about artistic heroism in the face of incredible odds. Any creative project is full of challenges and Howard had his share, but once his diagnosis happened, his story takes a turn and becomes a race to turn out work, while he is literally fighting for his life. His work from the last few years of his life is astounding, not just in terms of songwriting, but also with screenwriting and contributing to the stories of so many films. In looking at all the hours of archival film we gathered, I was always looking for moments where I could put the audience in the room with Howard. I wanted you, the viewer, to be a fly on the wall and see the moments of struggle and creation. It’s one thing to say that Howard was a good director; it’s another to show him working with Jodi Benson on The Little Mermaid and getting every ounce of performance out of her. Or to hear him work with Marvin Hamlisch and hear the frustration in his voice. Or to see him at the recording session with Angela Lansbury and Jerry Orbach, where he’s totally focused on getting the best performance and totally thrilled when he listens to playback with them. For the audience to be there with us all in that room when we were making these films…that’s what I tried to do at every turn. That’s why the story is told with 30-year-old video clips, stills and bits of audio from another age, an analog age, when Howard was at his finest. That’s why there are no talking heads or breathless narrators. I wanted to transport you to that time to bring Howard back and let the audience spend 90 minutes with this most amazing man.

Filmmaker: Every time I see a song in any film musical I remember Howard’s rule that each number has to progress the story. I see that in films up to the present, like in Moana, and wonder about his broader influence on the films you made at Disney soon after his passing, such as The Lion King and The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and also whether you see his influence in animation today.

Hahn: I’m sure that Howard’s influence was felt in subsequent films at Disney. Although there was no replacement for Howard, we did have Tim Rice as our lyricist on Lion King and Tim even stepped in to finish Aladdin when Howard passed away. Howard’s influence was felt because he showed that filmed musicals could have a dynamic home in animation. All the following films were able to build on that idea. Howard brought back the musical theatre genre to the studio that had once used it very successfully on films like Snow White, Pinocchio and Peter Pan. But he refreshed the genre and made it relevant to audiences in his era and in doing so brought back the popularity of animation to a generation of filmgoers.

Filmmaker: This might be impossible to answer, but what do you think Howard Ashman would think about the world today, our political situation or artistic works? What might he be working on if he were here now?

Hahn: This is impossible to answer. Howard wasn’t into writing political theatre; he was an entertainer. He would likely have strong opinions about the world we live in, but his work was about entertaining audiences with clever writing and smart lyrics. It’s even more impossible to predict what Howard would be working on. He once told Alan that he’d love to have a children’s theatre so that he could pay forward some of the experiences he had as a kid, but beyond that who knows. This is, after all, the guy who saw a hit musical in Roger Corman’s Little Shop of Horrors, so no one could imagine what would have been next.