Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

DP Larkin Seiple Breaks Down Every Shot from Childish Gambino’s “This Is America “

Since its May 5th launch, Childish Gambino’s “This Is America” video has been viewed more than 215 million times on YouTube, a testament to the power of the internet as mass medium. According to Variety, the average ticket price for the first quarter of 2018 is $9.16; using that math, a music video shot in two days with nine rolls of film has been viewed by as many people as Avengers: Infinity War.

“I was a bit shocked at the scale and speed of the reaction. It was released on a Saturday evening and on Sunday morning I woke up to my phone buzzing with texts about the video,” said This Is America cinematographer Larkin Seiple (Swiss Army Man, Bleed for This). “I really didn’t expect it to take off the way it did, and then the meme economy just exploded. It’s been pretty fun to browse the internet and see what images people have taken from the video and made into something else.”

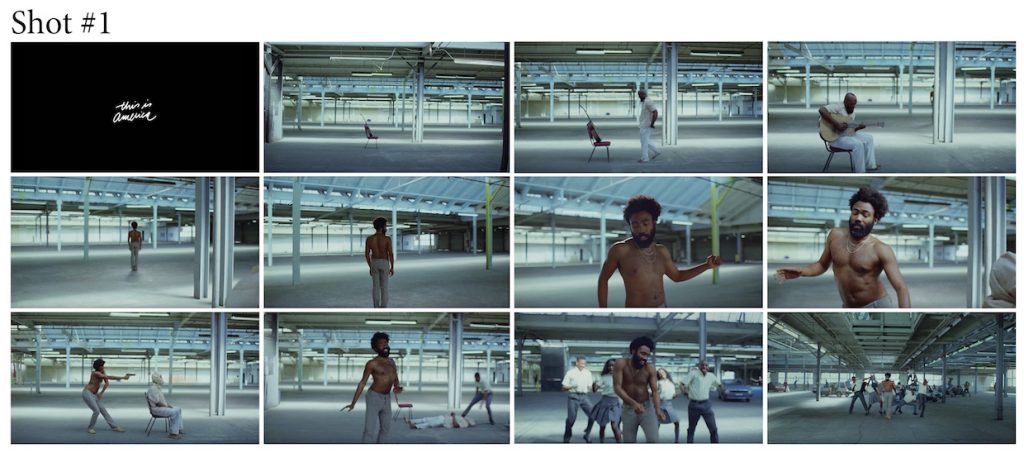

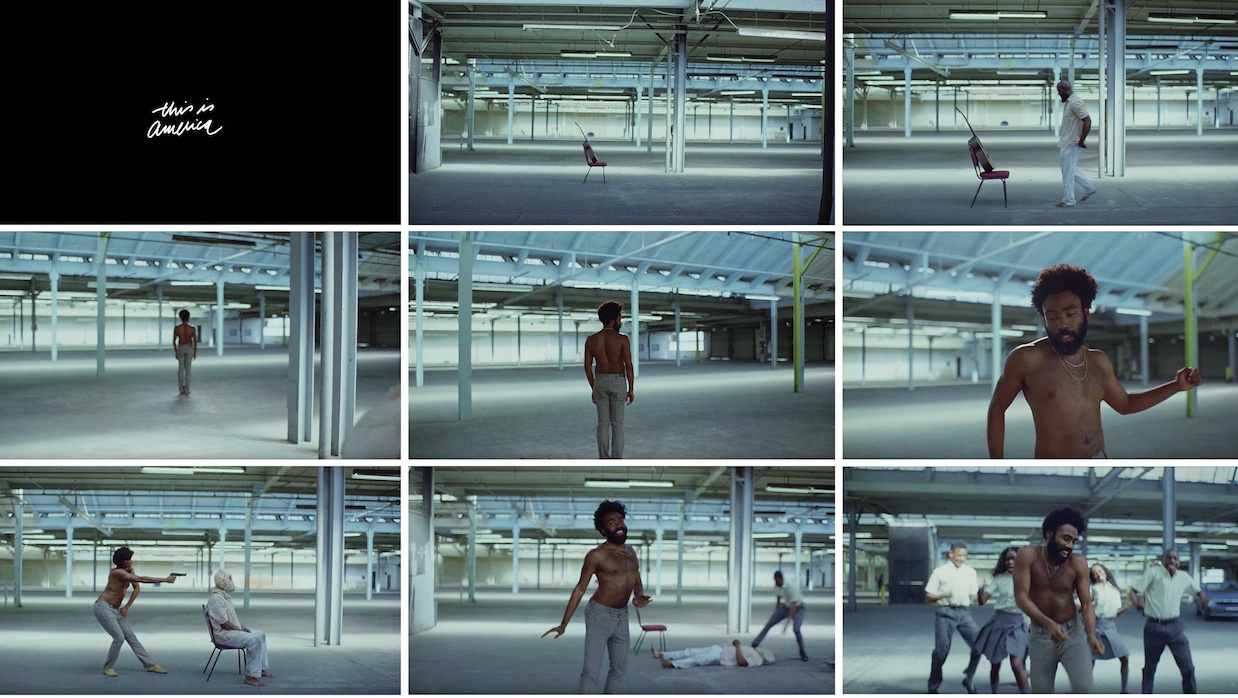

Armed with roughly an hour of celluloid, Seiple and his crew shot This Is America over two days in an old Firestone factory in South Los Angeles in late April—less than two weeks before the video debuted to coincide with Childish Gambino’s performance on Saturday Night Live. The video entirely consists of six Steadicam tracking shots, each of which Seiple broke down for Filmmaker. Check out more of Larkin’s music video work here.

Filmmaker: Let’s start with the decision to shoot on film.

Seiple: It was actually Donald Glover’s [aka Childish Gambino’s] request. [This Is America director] Hiro Murai and I jumped at the chance to shoot celluloid, which spoke to a more timeless and organic look. Film was the perfect medium for that. We shot on 3-perf 35mm, and because we were shooting film we only had so many takes that we could do, which meant we spent a lot of time rehearsing the bigger set-ups. We would build up the background elements, then we would strip things away and make it sparser. We probably did 10 takes of the first set-up and thought we were good. Then we checked the gate and we had a hair in the gate, so we had to do another five takes. We only had ten rolls of film for the whole shoot, so we got a little nervous. I think we freaked production out and they sent a runner to pick up two more rolls for the second day [of the two-day shoot]. We actually only ended up using nine rolls.

Filmmaker: Were they all 400-foot rolls?

Seiple: Yeah. We actually used some resold, unopened thousand-foot rolls. FotoKem cut them into 400-foot rolls for us.

Filmmaker: So if a 400-foot load is five minutes of film, you only had about an hour of total footage you could shoot?

Seiple: Yeah, that’s why we were pretty nervous. We also knew the final scene was going to be 60 [frames per second], which didn’t help our fears. We weren’t supposed to [shoot off-speed] initially. We were supposed to be shooting on an Arricam LT from [rental house] Keslow Camera, because they have great HD taps and we needed to be able to see what was happening in the background. Our Steadicam operator, Brian Freesh, was really amped about getting the LT, because it’s a much lighter camera. Then, at the last minute, we realized we needed to go to 60 frames per second. So, we had to switch the body over to the heavier Arricam Studio for the shoot, which made it a little more challenging for Brian but he never complained.

Filmmaker: Tell me about your lenses and film stock.

Seiple: We shot Vision 3 500T 5219. It’s Kodak’s fastest stock and has a lovely level of grain for what we were going for. We exposed normally, and even a bit overexposed for some shots to help build some contrast for the brighter scenes. For glass we jumped between Zeiss Super Speeds and the Angenieux EZ-1 30-90mm zoom. We shot the Supers around a T2.8 so [that] the highlights didn’t shift blue or purple from the chromatic aberration, but also to allow us to see deeper in the background. Normally I wouldn’t use glass as sharp as the EZ zoom on a digital project, but on film you can use sharp glass and it still renders in a really organic way.

Filmmaker: I watched the video in 1080p on YouTube and there was a significant amount of digital noise and what looks like grain. How much of that grain comes from shooting on film and how much is just the compression you get on YouTube?

Seiple: It’s tricky. Even at 1080, I’m still not happy with the way it looks on YouTube. There’s just so much compression. It’s actually not that grainy. It’s film, so there’s going to be some grain and texture, but that’s not why we shot film. It was more for the way film picks out subtle colors and the way it rendered Donald’s skin.

Filmmaker: Did you always envision the shoot taking place in this sprawling industrial space?

Seiple: We scouted a bunch of places. If you look at the video, the location doesn’t necessarily scream out that it had to be shot there, but it ended up being the most interesting place we looked at. We didn’t realize how huge it was at first. There’s warehouse upon warehouse upon warehouse in this old Firestone factory in South Los Angeles. I didn’t know this at the time, but I guess a lot of music videos used to shoot there back when music videos were a lot bigger. We loved it because it’s industrial but clean and controlled. It felt more like an installation space, as opposed to something apocalyptic. We originally looked at the abandoned Hawthorne Mall as well, which is this amazing location with broken down escalators and all these shafts of light, but it just felt too dramatic for what we were trying to do. We thought it might steal attention from what Donald and the dancers were doing.

Filmmaker: Didn’t they shoot some of Westworld in that mall?

Seiple: A bunch of things have shot there. Westworld shot there. There’s a scene from Gone Girl that shot there. There was a Drake music video that shot there that you can’t even tell because it’s all close-ups. It’s a great location, but it’s becoming more and more popular, and that was also part of the reason we went another direction.

Filmmaker: Are all the shots in the video done on Steadicam?

Seiple: It’s all Steadicam, but we also used a Grip Trix electronic cart for a couple of shots, which is like a high-powered golf cart that you can mount the Steadicam onto.

Filmmaker: Was the plan always to just have the six shots that are in the final video?

Seiple: We would start each scene with these very basic ideas, then they would evolve. Like in the first shot: initially we were going to reveal Donald, and when Donald pulled the trigger [of the gun] the dancers were going to come in, then we were going to cut. But as we did it Hiro and Donald were like, “We can keep it going.” As we were shooting we realized that it was kind of hypnotic to [extend the takes], so we kept finding ways to make the shots longer and longer, stretching them out until we had to have a dramatic reset.

Filmmaker: How did you approach lighting a space this big?

Seiple: Our approach was to schedule around the sun. We kept the existing fluorescents on, as we liked the little bit of green spill they put in the background, but they didn’t actually [carry enough] to do much lighting. We timed the start of this shot so that the sun was backlighting it, but by the time we got the take perfect the sun had moved to a more frontal light, which we actually enjoyed more. For those later takes we put in Digital Sputnik beams, which were just two arrays of 18 Digital Sputnik lights that we put in behind Donald to give him a little edge to pop him from the background.

We were going in and out of clouds throughout the day, but luckily we landed on this really lovely time of day, where the sunlight was coming through the windows but most of it wasn’t quite directional. So there’s this nice ambience that Donald eventually walks through that has this harder shape to it and makes his chest pop out a bit more. Originally the guitarist was in that beam of light as well. We kept moving his chair back further and further to keep him in that light as the sun moved. By the time we [shot the take that we used in the video], the light had moved so far back that we just left him in the shade, which I actually think looks more interesting.

Filmmaker:What millimeter lens did you use for this shot?

Seiple: Pretty sure it was a 35mm Super Speed for this scene at around a T2.8. We had neutral density filters in, and we were overexposing by about a half-stop just to make it a richer image and bring out the highlights a bit more. When we watched the video back, we thought, “We probably should’ve shot at T5.6 so we could feel the background just a little bit more.” A lot of the images that we were looking at for references were very deep focus. We looked at Alex Webb’s photography, which has a lot of texture and these colorful backgrounds. There’s a great photo that René Burri took of these two men dancing in hard sunlight that was a big vibe for what we were shooting.

Filmmaker: Were most of your references still photographers?

Seiple: For this project we didn’t look at any moving images for references. Hiro and I just exchanged collections of photos that were more about texture and tone, and also a bit about the blocking as well. Alex Webb’s photography is stunning. He finds these frames among chaos that stand out. Hiro sent those to me, then I sent him some René Burri and Josef Koudelka. It was mainly those three photographers.

Seiple: At this old Firestone plant there was this giant flat with a random door at the end of it. It was a very surreal thing to see. We added a red stripe to it to make it feel a bit more industrial, then we created a very presentational image of a choir, then Donald pops out of that door like Bugs Bunny. That’s one of my favorite parts of the video. We shot that at the end of the day when the sunlight was coming through the windows. We used silver ame to bounce light back to pop Donald’s eyes a bit and give him an edge as he walks by the police car at the end of the shot.

This was a really hard shot to do [with] Steadicam. Brian had to sprint into the shot, brush past the choir like a foot from their faces, then rip backwards. While doing that, he had to keep the headroom perfect, because that wall ends pretty abruptly. He was literally framing [the top of the wall] on the line every time. We didn’t want to do a digital punch-in, because we knew Donald was also going to be on the edge of frame when he comes through the door. It was a very delicate focus pull; our 1st Assistant Camera Matt Sanderson sprinted right along Brian each time.

I don’t believe the people in the choir had ever been in a choir before. [laughs] Their choreography took a while to get down and we kept changing who was standing where. If you look at it, they’re not really in sync. Surprisingly, they did sell the [bullet] hits pretty well. We had to go in for the final take and lay down stunt pads on the little deck that we had built. All the choir members were wearing kneepads underneath their robes.

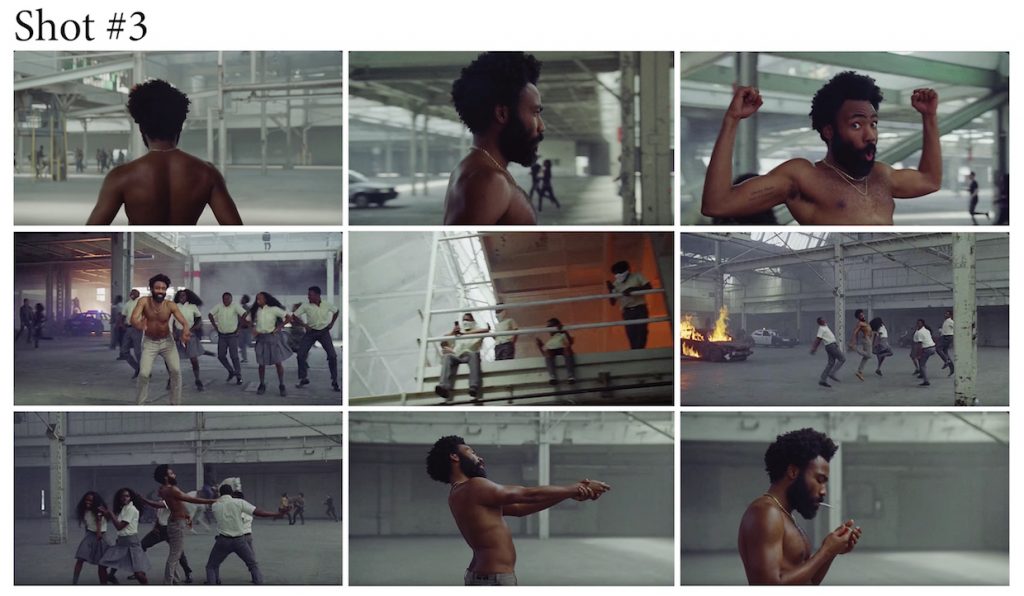

Seiple: This was the hardest shot to block. We had a lot going on: a horse, a car on fire, a man jumping off a ledge, a lot of cops in riot gear and people looting. But even though all those things were going on in the background, we weren’t trying to divert attention back there—it was more about what Donald and the dancers were doing in the foreground. Initially we were going to do a big push through the warehouse. After a couple of hours of working with Donald and the dancers, we realized that it would be a lot more interesting if the shot started with Donald walking into frame and the camera wrapping around him. So we would be focused on him, but we could still take in all the details behind him as the camera moved around him in a 360. We probably did 20 rehearsals, which was pretty stressful because most of the background were sprinting, there was a car on fire, the building was filling up with smoke and the fire marshal was not happy.

Filmmaker: When you do that tilt up to the kids on the second floor, do Donald and the dancers basically just run over to their next position so the camera can find them when it tilts back down?

Seiple: Yeah. As soon as the camera went up, they all hustled over and started doing that kick circle. The first couple of takes Brian kept getting to them too quickly, so we had to let it breathe a little bit. The camera is also doing a slow zoom during the entire second half of the scene. It’s subtle, but it starts at 30mm and ends at 90mm. The only lighting for that was those same Digital Sputnik beams we used for the first shot. Our gaffer, Matt Ardine, buried them in the background to mimic fire and to backlight the smoke.

Seiple: We shot this with the Steadicam on the Grip Trix. There’s also a cameo from SZA in there, sitting on the hood of the car. We had to light her, because at that point in the day the sun was becoming too dramatic and she was just a shadow. This shot wasn’t too crazy. I think we did it in five takes. We did do a lot of rehearsals, though. When you’re shooting with film, you make sure the rehearsal is working nicely and then you start rolling.

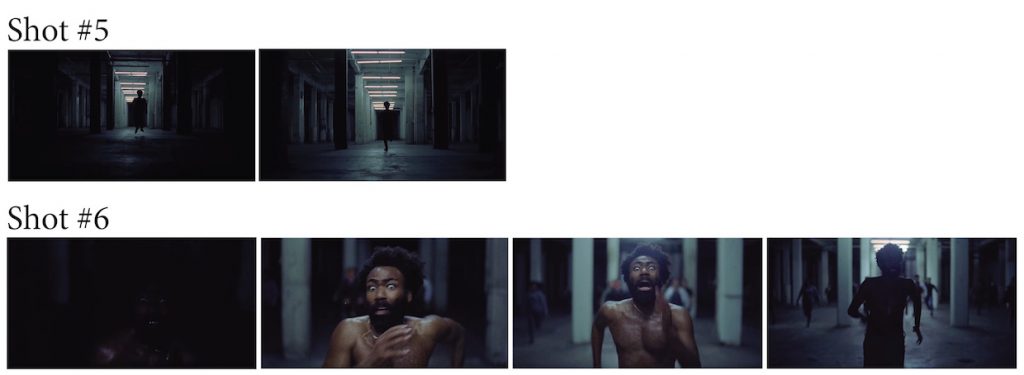

We found a way to transition from this shot into the basement [location used for the following shot] by using this flat that our production designer, Jason Kisvarday, built. It had a doorway cut out on a gray wall. As the camera pulled back through it we tilted up into the wall, and used that to blend into the floor of the basement in the next shot as we tilted up to find Donald running under these fluorescents.

Seiple: For these shots we had to put little gyro stabilizers on top of the Steadicam, little orbs that spin at some insane rate like 20,000 RPMs. The Steadicam was mounted to the Grip Trix driving full speed, so the wind was a real issue. You mount [the gyro stabilizers] onto the arm of the Steadicam and basically it stops the Steadicam from dramatically shaking, but they take 10 minutes to warm up. That’s the ridiculous part. You turn them on, and for them to get up to speed it takes 10 minutes.

In the basement of the Firestone building there’s hundreds of fluorescents. Luckily, most of them were on a breaker that we could turn off, but there were still probably 20 or 30 bulbs that we had to bring in a scissor lift to unscrew. We wanted to create this pool of light that Donald’s running towards in silhouette. For that shot, we mounted a 4’ x 2’ LED panel onto the Grip Trix. Matt Ardine designed that light. It’s basically like a LiteMat, but he built it before LiteMats were around. We called it a MattyPad. The light was about two to three stops under, as we just wanted to pick out reflections on Donald’s skin. Also, I don’t know if anyone’s picked up on it, but the runners in the last shot aren’t moving their arms. It’s subtle, but they’re almost running like zombies. Hiro added that for the last take.

Matt Mulcahey works as a DIT in the Midwest. He also writes about film on his blog Deep Fried Movies.