Back to selection

Back to selection

Elementary Force: Claire Denis on High Life

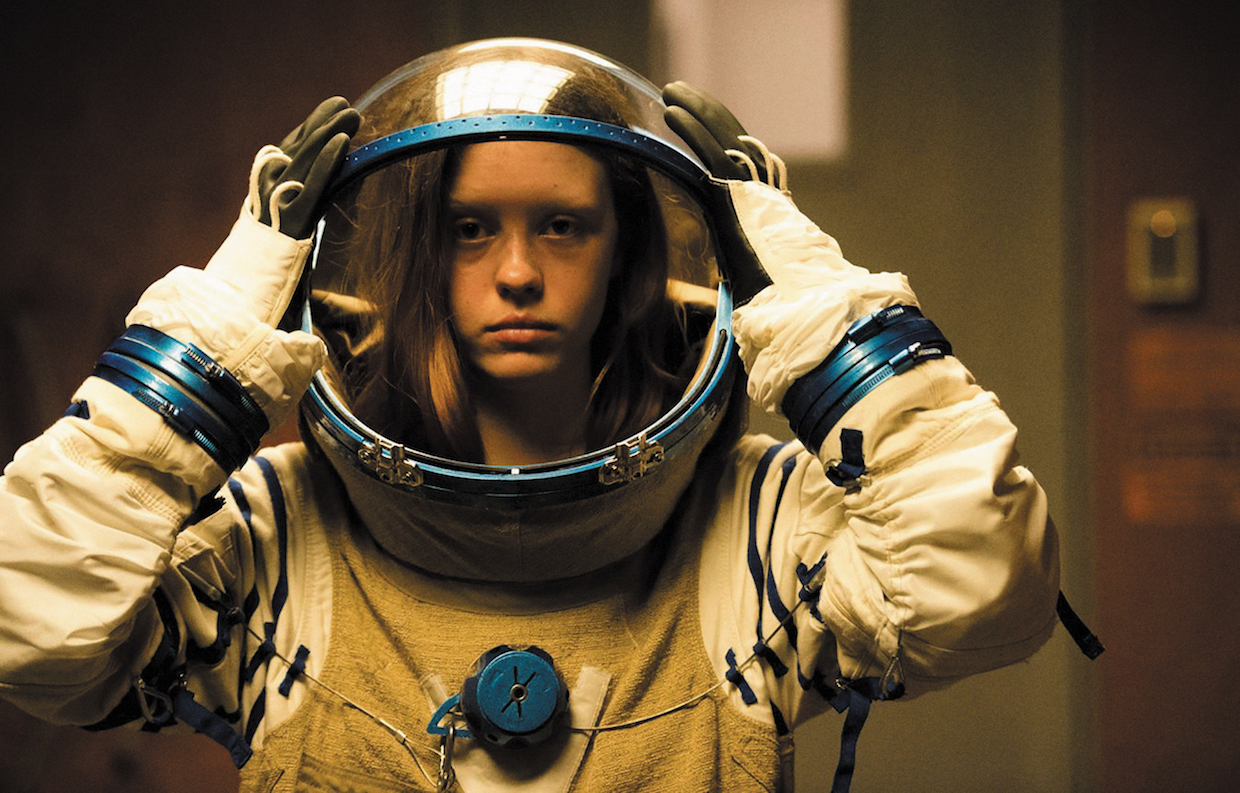

Mia Goth in High Life

Mia Goth in High Life No one expected Claire Denis to soften with age. At 72, the French auteur has been a daring and unpredictable force in cinema for three decades now. After delivering last year’s talky romantic comedy Let the Sunshine In, which offered the unexpected sight of Gérard Depardieu as a lovesick psychic, Denis has returned with a certified leap into the unknown.

High Life is the filmmaker’s first English-language film, her first science fiction foray, and her first featuring eye-popping CGI. Boasting an international cast that includes Robert Pattinson, Juliette Binoche, Mia Goth and André Benjamin, and set to be released by A24 on April 12, High Life could very well introduce the legendary director to a whole new generation of filmgoers. But it’s anyone’s guess what newcomers will make of Denis’s startling vision.

From its unassuming opening shot of a verdant garden filled with dewy melons to its sublime final image—one of pure cinematic abstraction—High Life twists against the expectations of its genre. Set aboard a space ship hurtling toward a black hole, the film offers a dark and unexpectedly erotic trip into existential oblivion. Despite its heady themes, the film’s depiction of carnal desire among doomed convicts on an interstellar suicide mission underscores Denis’s corporeal obsessions.

In a certain light, High Life represents a culmination of Denis’s cinematic obsessions, the seeds of which can be traced back to her 1990 neo-noir classic, No Fear, No Die. That film, set in the Parisian underworld of illegal cockfighting, set the template for Denis’s haunted visions of outcasts and misfits living on the margins of society. Throughout her career, she has mined this territory in genres ranging from comedy (Nénette et Boni) to horror (Trouble Every Day) to drama (The Intruder) and thriller (Bastards).

High Life is spiked with noir-ish fatalism, reminiscent of the Chester Himes quotation that Denis uses to open No Fear: “Every human being, whatever his race, nationality, religion or politics, is capable of anything and everything.” It answers why Denis would be interested in making a film about a prison space in the first place—to see how we behave in a world without hope. What are we capable of when the rules governing life are cast aside? The answer: anything.

Our innate potential to exceed or transgress beyond our wildest fantasies lies at the core of High Life. The basic premise of the film is that in the near future, convicts can volunteer as scientific guinea pigs on space missions rather than serve out life sentences on earth. Monte, played with eerie ambiguity by Pattinson, is one such specimen. While the other prisoners rage and despair, Monte keeps to himself, spending his days tending the spaceship’s onboard garden and helping maintain a semblance of order as tensions run high.

The opening sequence—one of the film’s most mesmerizing and most jarring—shows Monte floating outside the spaceship, conducting a repair while a baby girl cries alone on board the retro-looking spaceship. It culminates with Monte’s workmanlike disposal of the bodies of his fellow prisoners. From there, we flash back to meet the addled crew, who freely roam the boxy spaceship in exchange for donating eggs and sperm to the libidinous fertility doctor—played by Binoche in a long witch’s braid—whose mission is to keep humanity alive.

I sat down with the director to discuss writing the film with longtime collaborator Jean-Pol Fargeau, the surprise casting of Robert Pattinson and the taboo at the heart of the film.

Filmmaker: In many ways, High Life is a radical departure for you. Yet, it’s still very much a Claire Denis film. I know it has been in the works for a long time. Can you talk about the origins of the idea?

Denis: I told Vincent Gallo once, “I could imagine you being happy alone in space, raising a baby girl to be the perfect woman for you.” This was after we made Trouble Every Day. And he said, “Yeah, that would be great!” It was really just a joke, this idea. Later, an English producer named Oliver Dungey asked me if I would ever make a film in English. I told him that I would do it only when I felt that English was the only language to speak in for the film. I started thinking about astronauts and people in space speaking Russian or English—or maybe Chinese, now—and told him I needed time to develop this idea. He said, “I think you should do something with a femme fatale.” I thought, “Well, maybe I’ll forget about the femme fatale!” But in the end, what I told Vincent was still there with me. I started working on [the idea] absolutely not thinking, “This is a science fiction movie.”

Filmmaker: You co-wrote the screenplay with Jean-Pol Fargeau, with whom you’ve collaborated on 10 films. I’m curious about how you work together, especially on a project like this, which is quite complex. Not only does it combine science fiction, erotic thriller and chamber drama, there are flashbacks and a voiceover.

Denis: With Jean-Pol, the best way to work is together. Not that I don’t trust him, but the fun is [being] together. When we first met, he was living in Marseille, so I would always go there to work with him. Now he lives in Paris, so we meet there. In a way, I preferred it when he was in Marseille. I was cut off from my life in Paris and completely devoted to the script. Now that we are both in Paris, I feel it’s more difficult to concentrate.

The first very important thing for us was working out the beginning of the film: the garden, the baby, and Monte—that first evening, let’s say, until [Monte] throws the corpses off the ship. That took us months to work out. I knew I wanted that to be the beginning of the film, and I knew this meant using flashbacks. So, Jean-Pol and I, we speak and speak. We discuss the continuity of the beginning. We write it together at the table. And if that works, the trouble then is the flashback. Jean-Pol was working on his side, and I was working on my side. Only when we figured out some of the flashbacks did we start working on [Monte’s] voiceover. Originally, there was much more voiceover and explanation, but we reduced it. We already knew the third part of the story was going to be simple, with not much dialogue. The most difficult part was the first section and the flashbacks.

Filmmaker; The author Zadie Smith was attached early on to co-write the screenplay, but you disagreed about the vision of the film. She wanted the prisoners to return to earth, whereas you were adamant that Monte and his crew are never giving that opportunity. As you’ve said elsewhere, High Life is not a “coming home” film.

Denis: When I started to properly write the script with Jean-Pol, I thought, “OK, now it’s time to be serious.” So I went and met with an astrophysicist and philosopher named Aurélien Barrau, who is famous in France. He had been working with the writer Jean-Luc Nancy, which is how I knew him. Aurélien teaches in Grenoble, so Jean-Pol and I went to his class. I told him that he needed to explain a few things to me. At that point, I had this idea about convicts in space, but I didn’t want the film to take place in our solar system. I wanted there to be no return. The convicts don’t know this, but I wanted to make sure they were too far to ever return. I didn’t want this film where you can see Earth on the horizon. We did a quick first draft. It was exciting. We had the doctor character there already, the “fuck box,” the garden—pretty much the film—but it was [written] in French. Oliver [Dungey] wanted it to be translated, which took some time. Of course, [the film] had to be shot in a studio, and we needed [it to be] a German coproduction. By the time we were working on the English version, we realized that there wasn’t enough money to make the film. It took a long time.

Filmmaker: The film has an eclectic and high profile cast. I’m curious how the casting process influenced the film’s evolution.

Denis: I started working with this Scottish casting director [Des Hamilton]. I went to London, and he read the script. We got along very well. It was a long process to cast this film. We were missing money. Everyone thought we needed to find a big star like Daniel Craig [to play Monte]. But I felt this had to be according to me. I have nothing against stars, but I wanted someone I could feel for. Not that I couldn’t feel for Daniel Craig, but he was so busy. I went to Pinewood Studios to meet with him, and he was in the middle of shooting James Bond. I thought, “OK, I need something where there [is] more commitment.” In my mind, always, when we were writing the script, I thought of Philip Seymour Hoffman. I saw Monte as this middle-aged guy on death row—desperate, with no family, with a kind of suicidal tendency to escape, someone without hope. Then this great actor died. He was a star, but he was someone I really thought I could work with, had he accepted the role. But the suicidal thing really frightened me.

Filmaker: Hoffman would have been incredible, but it also would have been a very different film. Having seen High Life twice, it’s hard for me to imagine anyone other than Robert Pattinson playing Monte.

Denis: When the casting director first told me that Robert Pattinson was very interested in meeting me, I thought, “Ha ha ha, c’mon!” I thought it was a joke! He took a train from London to Paris [to meet me]. Later I went to Los Angeles and spent more time with Robert. I told him, “There’s very little chance [that I’d cast you]. You’re too young. It’s not possible.” But we continued to talk very openly, and by the time I left LA I realized he was really the kind of actor I like. He has this kind of mystery in him that he won’t share. There’s something inside, you know? I said, “That’s it. It’s him.” Robert was surprised that I made the decision.

We began to see each other more often. He was living in London at the time, so it was easy to meet. We would go to the theater together; we enjoyed being together. But the money [to make the film] was still not there. He waited on us. He said, “You thought I was too young, but maybe I’ll be too old by the time you make it.” When we got the money, I was just finishing Let the Sunshine In. It was really [producer] Andrew Lauren who made it possible. By that time, Patricia Arquette had been waiting two years [to make the movie] and was doing a TV show and couldn’t be ready for our dates. At Cannes, Juliette [Binoche] said, “You know, Claire, I think I can do the role easily.” No, she didn’t say “easily”—“happily.” I said, “OK, but we need to change the role.” I had only two months from one film to the other. It was crazy. I was so afraid to have so little preproduction time. But I told the producer, “I’ll do it for Robert. He’s been waiting four years.”

Filmmaker: I’ve always felt that your films are more about an actor’s presence than their performance. It’s about capturing their physical being. In this respect, Pattinson seems perfect for the film. There are long passages where we simply observe his face, and he’s able to convey this mixture of tenderness and pain that keeps you on edge. Monte seems like someone capable of anything.

Denis: Yes. It was already like this in Twilight. I was amazed by him and by [Kristen Stewart], too. He’s able to do a lot of things, you know? I think Cosmopolis was really a moment for me. I was hesitating because he’s so young and so good-looking. But he’s not working like a star. He’s like Juliette, he has something mysterious about him. Sometimes, when we were shooting, I did not understand what was happening exactly, but he was ready to do [it] without being sure. While we were shooting, I completely forgot he was a star, you know? When he was in London, he was happy. Now that he’s in Los Angeles constantly, I’m afraid. He’s so well protected by agents. Of course they cherish him, and of course they are nice to him, but they are like a sort of family and I don’t think it’s such a good idea. Juliette has two agents, but she’s the boss. She says what she wants. Nobody is around her. She travels on her own. When we were shooting in Germany, I wanted Robert on his own. He was alone. The makeup person was from Poland and I said, “That’s it.”

Filmmaker: Let’s talk about cinematography. The scenes aboard the space ship have a kind of hard, synthetic HD look, whereas the flashbacks to life on earth are shot on 16mm. This is also the first time you worked with Yorick Le Saux instead of Agnès Godard, who shot many of your most celebrated films, including my personal favorite, The Intruder.

Denis: That film was a miracle. The producer [Humbert Balsan] is now dead, and probably I will never meet another crazy, beautiful man like that again. Agnès and I were so happy when we were making that film. But after making Sunshine, Agnès was tired, in a way, [and] also tired of me. We shot with the Sony [F65]—a terrible machine—and did it in five weeks. She knew [High Life] was going to be difficult, so she said, “Maybe you should go with someone else.” With Yorick, we had something in mind immediately: to equip the set as it would be on a real spaceship, with lights and everything controlled by computer. You would be able to set it to all the different conditions of day and night. Knowing Agnès, she would have accepted this because it was a logical idea, but she would have suffered. Also, she wanted to work with her own team, [but] Yorick agreed to work with a German crew, and that was important for the coproduction. We shot in Cologne in a small studio next door to where Jim Jarmusch shot Only Lovers Left Alive with Yorick. We chose the same studio where Lars von Trier shot Nymphomaniac. That’s actually where I saw Mia Goth for the first time. Our casting director also works for Lars. We shot the exteriors in 16mm. Originally, I wanted to shoot them in New Orleans. That was in the script—the hobo train. But in the end, we had to shoot them in eastern Poland.

Filmmaker: There are a few very brief shots in the film on board the spaceship that look almost like surveillance video. They’re spliced in very quickly and not explained. I loved what they did visually and also how they set me on edge.

Denis: It’s crazy. I have an old video camera. I don’t know why, but I took it [for a] camera test, saw the result and was completely crazy. I said to Yorick, “Let’s use it.” I wanted to do the entire film [with that camera]. But it was not an easy thing to accept [for the producers]. So, when nobody was looking, Yorick and I would take it out and shoot a bit.

Filmmaker; The Icelandic–Danish artist Olafur Eliasson, known for high-tech installations that explore visual perception, is credited with creating some of the film’s visual effects. Can you talk about this collaboration?

Denis: I wanted much more from Olafur, but there wasn’t enough time. In the end, I only got the yellow light that you see at the end of the film. You know, Olafur was prophetic. He said, “If you want to work with me, don’t be tight [within] the coproduction; don’t be corporate. Just do it with me in my place.” But then the coproduction sort of freaked out, you know?

Filmmaker: Many of your films examine the intimacy of family relationships. High Life goes a step further. In the film’s final section, Monte and his now teenage daughter are the last remaining people in the world, and there’s the suggestion of a kind of incestuous potential between them. In a way, this taboo is the film’s main question.

Denis: It was always in my mind from the beginning. I thought, “This guy is alone with a baby girl, and he knows something.” He’s thinking, “By the time she’s 14, we’ll be dead.” Of course he understands [the situation]. For me, in the end, of course he’s the only man possible for her. But I also think she’s the only woman possible for him.

Filmmaker: I sense a kind of relief in your having finished High Life. It was a long struggle to make the film and was a complex project to execute on many levels. Now that it’s behind you, I’m wondering what your feelings are about filmmaking as you look ahead.

Denis: When we were shooting High Life, my mother died. We are emptying her apartment in Paris now because we had to sell it. During the shoot, I was taking a train every Saturday [from Cologne to Paris] to spend time with my mother in the hospital. I felt the obligation to return to set every Sunday was killing me slowly. She died on a Tuesday morning, so I wasn’t there. The loss of my mother during the shoot… I thought, if not for Robert and Mia—I know I was lucky working. People would say, “It’s so great to work!” I’d say “Yeah,” but it was so horrible not to be with her.” Now I don’t know. We’ll see. She saw all of my films. I think she was very keen on this one. She saw Robert and said, “Oh, [a] very good-looking young man!” Now I’m an orphan. My mother was dear to me. She was like my constant, my light. I think now I really want to go on working, working.