Back to selection

Back to selection

Put It in Writing: Living Through the Films of Abel Ferrara, Part One

Abel Ferrara in Driller Killer

Abel Ferrara in Driller Killer Evan Louison last wrote about Abel Ferrara for Filmmaker‘s 25th anniversary issue in his report, “Letter from Rome.” Given the assignment to interview Ferrara in conjunction with his month-long MoMA retrospective, Louison responded with a five-part personal memoir that tracks the impact of the director and his work on his own life. Check back each day this week for the next in the series.

- Nobody’s CLEAN

New York became our only school and we made that trip by train or else in Nicky’s black house painted VW a 1000 times… Seeing Kazan arguing with Nicholas Ray on a street corner… always ending on the Lower East Side, where five years or so later I saw Mean Streets and The Conformist back to back on the same afternoon and I knew I was to be a filmmaker or die and watching films was more or less over for me. —- Abel Ferrara, foreword to Clayton Patterson’s Captured.

There’s a line at the counter at your local public library in Eastern Suffolk and your mother’s waiting outside with the car running. But you’re nervous because you know what’s about to happen. You wait. Your place on line gets slowly closer to the checkout. You allow for your turn, fidgeting. When you’re finally at the counter, looking over what’s in your arms, you can only barely see the librarian who’s waiting on you. Trying not to meet her eye, you stack the pile of books — Crestwood Monster Series, Sherlock Holmes -— and videos — to be honest, it’s mostly videos — in front of the old woman. She peers down at you and you wait for what always happens.

Still you’ve got to try.

Your insides are all suspense — a familiar feeling, the anxiety of being found out. And all because you desire, and you’re curious — you want to know a forbidden thing.

The allure of the profane plays out as violence or obscenity when it comes to the moving image. You know this somehow intrinsically, like a reflex. It feels tied into your DNA like a birthmark. The summer prior, you’re caught smuggling pornography out of a store, an issue of Penthouse tucked neatly between the pages of your mother’s New York Times. You’re not sorry. Just ashamed of being caught. And it’s an experience you’re bound to repeat.

Here at the library you’ve tried everything already — just walking out, avoiding the checkout at the front, skirting past the sensor at the sliding doors, switching tapes in their cases. But each time you’re foiled. The librarians keep watch over the exit like nurses at a maternity ward, making sure the right title goes home with the right family.

Now the librarian scans each of the items in the pile and makes her way through them one by excruciating one until she stops and examines something in her hand. She turns the tape over and looks over the top of her rims.

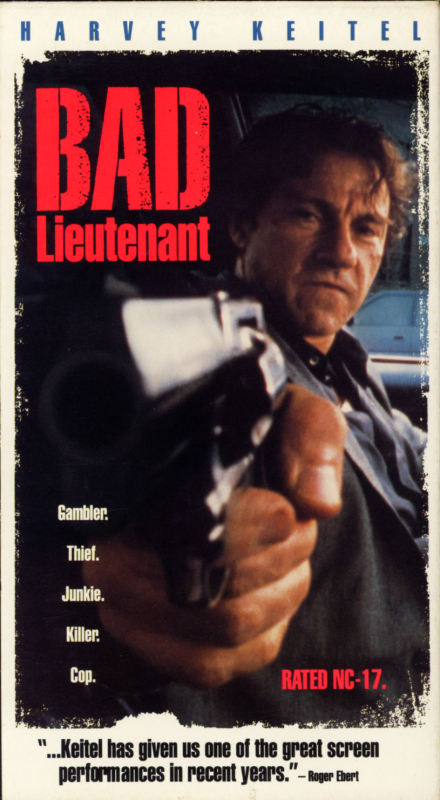

What’s this, she says and holds the video up.

You don’t say anything. You do your best to look innocent. Pretend it’s someone else’s contraband. Then she shakes her head and makes a face like she knows what you’re up to and says —

You’re not old enough for this one… See?

She’s pointing to a little icon in the corner of the cover.

“NC-17.”

She smiles down at you holding the tape and pointing at the adults-only rating.

But all you can see is the weapon.

The man’s eyes behind the fist holding it.

Staring down the barrel at you.

Daring you to look back.

Meet his gaze.

The frenzy.

Words stacked on top of each other below his face reading:

Thief

Junkie

Killer

Cop

It’s not the first time you’ve been so transfixed by this face, these words, the story they tell. And it won’t be the last. From that age on your connection with the film and its maker is forged. The tape’s contents were denied to you for your own good, yet inside something beckons you to it all the same. You just know you’ve got to have it, know it. It’s a part of you.

You’re ten years old.

Any attempt I could make to soft-pedal the impact seeing Bad Lieutenant made on my life, I would be lying. I was young, perhaps too young, perhaps way too young. Nevertheless, wayward and secretive, awkward and shy, I became obsessed with the work of Abel Ferrara — even before I had seen one of his films. Forget aesthetics or sensibilities that even now I’ve yet to put into practice, because I haven’t made films of my own that anyone would know. The experience of watching Abel’s films has informed my dreams and ideals to such massive degree that I find myself self-conscious admitting here, publicly, the wake this obsession has made. To finally put it in writing.

But the occasion of this assignment — to reckon with Abel’s body of work as it coincides with month-long retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art — warrants at least as much. MoMA, a sacred institution, where I spent many hours in my adolescence and young adult life, is truly where these works deserve to be shown and seen.

It took me another year after that moment in the Library to finally see what was on that tape and find others like it. But when I did, there was an immediate indelibility that leapt out at me, a peculiar energy that was common to all of these films. It’s the energy that reaches out of an old CRT TV set playing quietly, late at night, like the hand in Poltergeist. The energy that sucks you through the screen and transports you, against your will, to someplace where the violence lingers in the quiet. Each cut and frame, each time the pierce of a single note against an actor’s face rings out against the city at night — these elements combine in the cinematic equivalent of what Italians call la tempesta perfetta.

Inside these films exists a world you’ve never seen before and yet you also recognize — a New York that is and isn’t. That never was and always will be. And between these transverse elements, what amounts is a spell that borders on enchantment. And the name looming somewhere below the title.

Abel.

“There’s billions of people on Earth, man…

You’re gonna offend someone.”

Nowadays, narratives go on trial. We wonder if certain films from the past could be made today. If they should be made today. If certain narratives would ever reach an audience or be justified in public recognition. The written word is no different. Who would be so bold to publish the controversial and the daring when there is more fear of transgression and judgement than a willing hunger to cross the line? In The Addiction, the newly converted vampire Kathleen Conklin says, “The old adage… that those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it, is a lie. There is no history. Everything you are is eternally with you…”

So this process of reviving creative works from the past and measuring them against our uncertain present is not necessarily new. Every generation has looked back in either dismissal or reverence to those that ran before them. But the current era’s fashioning of outrage into a digital currency isn’t only symptomatic of a misguided, retroactive scythe. It’s a tyranny of purity. To employ a modern day-litmus test doesn’t just limit the culture. It denies us our history as well.

In many recent reviews of Abel’s work, his persona takes a center stage role, and knowing him, it’s easy to see why. If ever there was a larger-than-life spirit, it’s his. But in many of these profiles he and his work are positioned as some kind of novelty, or something to marvel at without truly considering. There’s a reticence in too many of these pieces to consider a unique voice without relegating it to the underbelly.

Whatever the reason, it is without question an oversight as well as a massive misunderstanding of the informed calculus that runs through all his films. Something is undoubtedly threatening for audiences, journalists, and critics in both his pictures and his identity — that of a troubled troublemaker. I will be the first to admit that it’s possible such willful, unguarded abandon is nowadays simply considered old fashioned. But I would say more likely, it is simply too free.

I don’t blame anyone who can’t grasp the magnitude of what Abel’s films have given us. How do you reckon with someone who won’t allow you to look beyond the past? Who demands that you confront the maelstrom without any numbing agent? But as it stands, when the public presently stands in judgement of our collective past, it is usually because we think we know better now.

This is not my first time writing this. Obsession and its byproducts are mainly alchemical, or neurochemical, and I’ve said so much about what these films mean before, and before, and before. But with this assignment comes an essential question:

How do you make your way around all points in a circle that makes up your life, that intersects the living body of work of another, and avoid marks already tread upon? Is there anything left worth examining? Anything more to say?

Because there’s no competing with the scholastic critiques already on record elsewhere. There’s no holding any candle to Nicole Brenez or Phillipe Met. So to conjure up yet another treatise on Abel’s work, to further attempt to dissect his resonance, to try and make some sense of what it all means, would be a waste. So instead, I write here only from a point of recall. From that point of self that was my own experience — as lived through these films.

“Tell it to God. To God.”

Sitting obediently on the altar in church, you nervously wait for the sermon to end. It’s the acolyte’s detail to assist in the preparation of the host. You’re anxious, trying to remember all the protocols at risk of slipping up yet again in front of the congregation. When the organ begins the communal interlude, you know the sacrament is next, and it fills you with dread. You used to stare at the stained-glass depictions of angels and wonder if you looked hard enough, if you could make them come to life.

In Sunday school and First Communion and Confirmation class for some reason they always call on you. One time when the priest gives the benediction of the cross to the students on their way out the classroom, you give it back to him. It’s a mistake. Off somewhere else, you were thinking what it looked like when the killer climbed up on the altar in The Fifth Power. The priest and instructors call you “Bishop” from then on. Someday, you think, they’ll know the joke is on them.

Like Abel, as a child you’re not so much taught to read the Good Book. It’s read to you by force. Church is the place where you first hear the story of two brothers, a jealous lesser who kills his elder, hides the body and lies about it. Were they twins? This young man Cain who ran astray, his guilt and banishment, and poor Abel, slain and memorialized in that classic complex of rivalry. A primal sin passing down across generations, this was the lesson in the verse. But there on the altar where you first hear that name — Abel — in moments you should be deep in prayer, you’re far away. Much later, when you see that name on the cover of a video, the effect is somehow immediate. That’s the thing about scripture. It sticks, if only subliminally.

When at first you are denied, try another way around. This becomes your ethos. The video store aisle is where you find your way into these pictures, at last. First as a customer and later as an employee, you pass through the same aisles where your father brought you as a child and rented the first movie you ever picked off a shelf — A Night at the Opera. You pass through the New Releases and gaze at the same title that caught your eye in the Library. The Bad Lieutenant glares back at you. You recognize the face and make eyes at him and keep going, pretending not to notice him. This is part of your plan. You circle round through another row and see a ghostlike face staring out of shadow, a mere silhouette of a man standing in a window, the glimmer of city lights reflected off his face. There’s something despairing in his eyes. You don’t know yet that it’s Frank White looking back at you. You only know the title — King of New York. You turn the box over and see it’s the same name at the bottom of the credits.

You watch through the racks as your siblings meander through the other sections. You’re hidden in with the Dramas like the characters on the boxes. You peer though the other titles to see if anyone’s paying you any mind.

But the clerk at the front is oblivious. You have no idea that’ll be you someday, in this very store, that he’s probably high as a kite.

Go on and do it, the voice says. You know you want to. So you pick the video in the clear plastic off the shelf and bound down the aisle, slowing only when you near the grownup who drove you there.

At the counter you shuffle respectfully up to the counter with your unwitting chaperone. Because you’ve mixed your plunder in with the rest of your siblings’ fare — Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken, Dick Tracy — it goes without remark by the clerk at the checkout. He just figures this parent has good taste. Likes cool stuff.

You can barely contain the excitement on the drive home. Sitting on your hands and pretending there’s nothing incredible about to happen, this is what it’s like to keep a secret. To learn how. This ride back to a place you’re afraid of, this forbidden thing you’ve stolen is the highlight of your life. You’ve gotten away with it and no one will ever know.

Always, those Friday nights when you could convince an adult with a car to escort you to American Video — these rides back were the only thing to look forward to. Like the moments between copping and getting high. These were movies you lived and breathed in secret. Your first private rituals. Things that became habits. Most kids you grew up with were only interested in what was new. What was popular. On television. Now decades have past and those kids are men who’ve forgotten you. But these movies that changed you haven’t lost their potency. They remain “Eternally with you.” And at this beginning of who you would become, your feeling separate was somehow comforted by a world of violent crime and corruption. What escape you found inside them. Late at night, playing these tapes, you’re the only paying ticketholder in an otherwise empty theatre. The movies play just for you.

I was so much older than the rest of my peers when I first got online that I will always consider the internet a new invention. We didn’t have a computer at home. In our family, we learned to type on a typewriter from a young age. Our mother was a secretary so maybe it was something in the blood. I would lay awake and listen to her typing up reports, late into the night hours, and once taught, I would keep everyone up with the sound of her Williams Sonoma’s keys flying, pounding out essays that were late because I’d left them to the last minute, like everything, like this assignment. Perhaps I was emulating her. Perhaps I was trying to achieve some element of control and independence. Even in grade school I was the only one in class who handed in book reports and social studies assignments that were typed. Because the feeling you could get hammering away at the keys was electric, the hum of the machine infectious, and this habit of staying up late and playing with words, watching them take shape and move around on a page in front of you became a pattern. And later, an addiction.

Soon homework assignments begin to carry references to the forbidden images you’d secreted away to view in private. Hints about this media become embedded in book reports like code. Suddenly, there’s a sense of danger in submitting these reports. You wait for the teacher to call your name, bring up to the desk for this trespass — for knowing the prohibited world of adults far too well.

You’re 15 in the library at your boarding school when finally you’re given access to a computer and the floodgates open. That chance to at last comb the obscure and trivial becomes another way out of the real world. Abel’s name is one of the first you ever enter into a search engine. The pictures of him that emerge contradict his words, riddled with vulnerabilities, with a disregard paid to all form of vanity. The laid bare quality of the icon, actively defiant of norms, perpetually leaning into its own legend — it’s all there, plainly evident right from the start.

You stay glued to the screen and become a fixture in the library. In the glass-enclosed computer lab unit, you’re always looking over your shoulder to make sure no one’s watching. By now this instinct has already become unshakeable. You find connections in the life stories of your idols wherever you can. Quickly this picture begins to take shape of someone emboldened to pick up the camera as a person to aspire to become. Always with the city in the visible distance, a place you yearn for, where things happen, where your father lives just a train ride away, somewhere you’ve yet to really know — you begin to feel drawn elsewhere.

This is the mid-90s, when everything seems possible to you. Names like Korine, Jarmusch, Van Sant, Gallo, and Ferrara abound in your mythology. These are your ports of entry into the cinema. You scour interviews and articles long since scrubbed from the digital realm, available only in archived old scans. Abel sees the camera as an extension of him. This is the first time you realize making films could be a way out of life. A parachute for breaking free of your upbringing. There’s a natural line of progression from the baseball diamond to music, to the movies, the lens and body of the camera just another instrument, like a guitar in your hands. It’s like a song. The films all start as songs, Abel says. But making movies? That’s life or death.

You write this down in your book. To remember it. And you do. Years later you can still recall words in your own handwriting, these pages where you first scrawl songs, dream up stories. Films you want to make someday. Films you’ll never make. You check out every published screenplay there is from the public library to the point where when you see the movies made from some of those scripts, you’ve imagined something completely different. Something better. Your movies. Your stories. These early attempts at screenwriting that you wish later you’d saved, that you can remember only pieces of, all of them were devoted to criminals on the run, daring escapes. But you did this all without any consciousness of what it means or why, just knowing all the while on some ulterior level, someday the time may come when it could be necessary to know how to do this. To create something out of nothing. Out of thin air. Perhaps even a matter of life or death.

This was how you escaped.

Evan Louison is a New York writer. Abel Ferrara:Unrated runs May 1-31st at the Museum of Modern Art.