Back to selection

Back to selection

State Of The Art : HDSLRs In 2010

It’s been nearly two years since Canon, Nikon and Panasonic started putting high-definition video technology into some of their medium-priced DSLR cameras. They did this without realizing how useful these new cameras could be to the professional filmmaking community. Tim Smith of Canon USA recently joked in an interview that most of the filmmakers he’d met did not know where to find the still-photograph function on their new cameras. In a way he’s right, but at this year’s NAB it was apparent that it is camera manufacturers who need to figure out how to make videography an even more efficient function on HDSLRs. None of the most useful innovations presented at NAB for these cameras were developed by Canon, Nikon or Panasonic. PL mounts for 35mm film lenses, remote control focusing and zoom software operated with iPhones, professional in-camera sound-recording systems, matte boxes and shoulder mounts were for the most part unveiled by small entrepreneurial companies and rental houses more closely attuned to the needs of filmmakers.

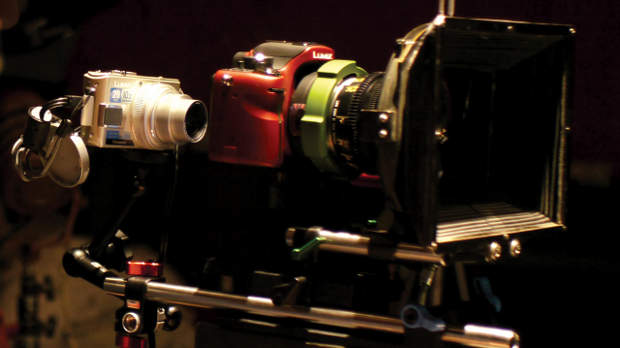

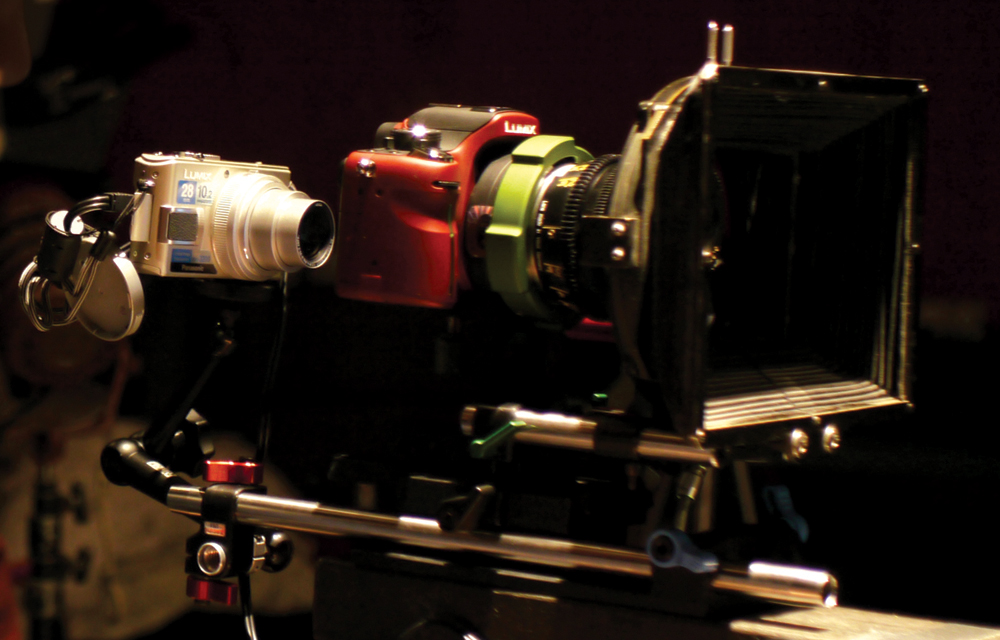

More and more still-camera companies (including cell phone manufacturers) are hopping on the HD video wagon, yet some of the d.p.s I spoke to for this article remain challenged by the limitations posed by HDSLRs at this stage of their development. Take for example the elaborate workaround Chris Chomyn and his crew devised on a video for Swiss recording artist Patje to make up for the fact that there’s no easy way to monitor the live HD signal of the Panasonic GH1 on an external monitor: “When we mounted the Panasonic GH1 on a Steadicam… the challenge became, ‘How does one operate a Steadicam without a monitor?’ By mounting another camera, an LX2, on a flex arm behind the GH1 and using the manual macrofocus function, we were able to shoot a full frame of the LCD on the back of the GH1. Then using the video out from the LX2, we sent that video signal to the Steadicam monitor and were able to both shoot HD as well as record the SD video on the LX2 of the LCD to give an alternative image for use in editing.” Whew! But for Chomyn as with many cinematographers, the quality and uniqueness of the image is what makes this technology a part of his regular arsenal. And isn’t half the fun of filmmaking overcoming obstacles such as these?

Nevertheless one of the most popular “after market” companies at NAB this year was Hot Rod Cameras, so I contacted its president, Illya Friedman, and asked why he thought the camera manufacturers are not anticipating the needs of filmmakers and why they seem content to play such a game of catch-up. “You could say the same thing about the journalists and d.p.s that initially dismissed HDSLR cameras as a ‘novelty’ but now realize the impact of these little cameras,” he said. “But I don’t think it’s fair to characterize it as ‘catch-up.’ Nikon and Canon are obviously very large companies. They’re diversified and build products to maximize return on investment. HDSLR cameras weren’t designed for professional use. The manufacturers were surprised by the swift acceptance on the sets of real professional productions. The fact that low-cost HDSLR cameras are being used in these capacities proves that the technological hurdles have been cleared to create not just acceptable but truly high-quality filmlike full-motion HD images. A new baseline for image quality has been set. I predict that much like computers and automobiles, HD camera technology is just entering an era where there will be many high-quality and relatively inexpensive products, and modest improvements in image quality will come with a premium price tag.”

Of course, it’s also possible that the well-publicized discovery by high-profile ASC cinematographers and A-list directors of what is possible with small and un-tethered HDSLRs just might raise the price of these miraculous tools. When you have veteran cinematographers like Brian Reynolds shooting TV shows (The Good Guys) with Sony F-35s as well as Canon 7Ds and Kodak Pocket Video cameras (used as “eyemos”), a successful show like House using nothing but Canon 5Ds on their season finale, and none other than George Lucas researching HDSLR technology for future projects, how long before more professional, higher-priced versions enter the market?

PANASONIC

Take the AG-AF100 as an example of what might be in store. Panasonic is putting much of their GH1 large-sensor technology into a body that will better meet the technical and ergonomic needs specific to narrative filmmakers. It will sell for $6,000 when it’s hatched at the end of 2010. Compare that to the $1,500 price tag on their first HDSLR, the GH1. The AG-AF100 camera uses a micro 4/3 short depth-of-field sensor like that on the GH1, but the body of the camera will actually be shaped like a small video camera.

Like the original GH1 it will be inexpensively compatible with anamorphic and other motion picture lenses by use of a PL lens adaptor. No other DSLR offers such easy compatibility right from the factory, at least not yet. The GH1 was also the first camera to take into account the need for built-in professional quality sound recording. But the AG-AF100 (also called the AVCCAM HD camcorder) moves forward in this area as well. It will feature a pair of XLR inputs, 48-kHz/16-bit two-channel digital audio recording, and support LPCM/Dolby-AC3, and a built-in stereo mic. And one more giant step forward still missing on other HDSLRs: time-code recording.

But the trade-off in using a Panasonic system is that compared to Canon and Nikon HDSLRs, all their models provide the least filmlike depth of field because of their relatively smaller 4/3 sensors. It’s still an incredible image though, and the new camcorder does record in both 1080 and 720 HD at 60, 30, 25 and 24 frames per second, right from the factory, even if it does require deinterlacing later (something friendly hackers at the discussion website DVXuser seem to have corrected). This, compatibility with PL-mounted lenses, and in-camera professional quality sound make Panasonic quite competitive with Canon and Nikon.

CANON

If engineers at Canon are not working nights and weekends trying to figure out how to make film camera lenses compatible with their HDSLRs, companies such as Hot Rod are stepping up to the task, and, according to cinematographers like Chomyn, doing so quite nicely.

Friedman tells me that for $3,250 you will be able to modify your Canon 7D so it accepts 35mm motion picture camera lenses natively without the loss of any light to the sensor or loss of edge-to-edge sharpness of the image, unlike a relay-lens adapter which before Hot Rod Cameras was the only way to put a PL-mount lens on an inexpensive HD camera. It takes about two weeks for Hot Rod to perform the camera transformation. Currently the company only converts the Canon 7D and 5D Mk II, but a PL-mount system for the 1D Mk IV will be available in August of 2010. The process is quite involved, but highly efficient. Friedman says they begin “by masking and sealing the imaging sensor cavity from the rest of the chamber so it’s not harmed for the rest of the process, then removing the mirror and original lens mount. The entire area is then flocked with an antireflective material and the penta prism is masked so that no light can flare the imaging sensor.” They then install “a PL-compatible lens mount and shim it so that the flange focal depth is accurate. If you are using calibrated lenses your focus marks will all line up.” Cool beans, but all that work around the “sensor cavity” makes me cringe like when I think of laser eye surgery. Hot Rods offers its own 2-year warranty for around $200 to replace the factory warranties nullified by making these kinds of changes to your camera.

The newest large-size sensor HDSLRs from Canon are the 1D and 7D. The 1D sells for around $5,000, but before you fall off your apple box over that price tag you should know you’re getting one of the largest sensors made for an HDSLR (27.9 x 18.6mm, or nearly the size of a 35mm frame) and an acceptably usable ISO (according to Canon) of 6400 — the best of all the Canons. But that sensor is still slightly smaller than the full-size sensor on the Canon 5D which sells for half the price. As you may recall, bigger sensor equals shallower depth of field, and that’s a good thing if you’re trying to get video to look like film.

When all the dust settles, what may well turn out to be the most popular camera with filmmakers (if it isn’t already) is the new 7D which sells for around $1,700 — $1,000 less than the 5D. Reynolds tells me that the 7D cuts seamlessly with the Sony F-35 and Panavision Genesis for action shots and that the studios he has worked for prefer the 7D over the 5D because the APS-C sensor on the 7D is smaller, enabling it to work with all motion picture lenses, whereas the larger sensors on the 5D or 1D severely limit the use of wider cine lenses that were not designed to cover such a large area.

I asked Chomyn what this difference in sensor sizes might mean in the field if different cameras were being used on the same shoot. He compared the 5D and 7D in his explanation: “…[First of all,] the same focal-length lens used on the 5D will appear ‘wider’ than on the 7D. All else being equal, the 5D will have shallower depth of field than the 7D…. In practical terms this means that under many close-up situations, using the 5D one would want a T-stop between 4 and 5.6 whereas for similar depth of field using the 7D, one might shoot at a 2.8 or 3.2. If one chooses to shoot with a 5D at a wider stop, there may prove to be focus issues. This could be adopted as a style or it may be distracting. Whatever the choice, it needs to be considered.” Chris also mentioned another matching consideration, and that is that the 5D sensor exhibits a lower signal-to-noise ratio.

Both the 7D and 1D shoot 60, 25 and 24 frames per second right from the factory —something the Canon 5D cannot do, at least not off the assembly line. But the good news for people with the 5D is that it is now finally able to shoot 25 and 24 frames per second as well as its original 30fps. This is due the Canon website right into your camera. The times we live in. Firmware is like software, except that it’s injected right into the cerebral cortex of your camera’s operating system instead of just floating around in there like a plug-in, and you’ll never really have to think of it again. An option for the new frames-per-second just appears on the menu like it came from the factory that way. Still, it’s an additional step current and near-future Canon 5D owners have to take.

All of the above mentioned Canons shoot 1080 and 720 HD. And in 720 mode, the 1D and 7D will also shoot at 60 frames per second. Anyone that has ever wanted to shoot close-ups of hands performing a task or other convoluted processes will understand the need for such slight slowing of motion; 48 frames per second would be better. It might seem puzzling why Canon would withhold these frame rates from the 5D firmware, but HD video on the 5D was developed for photojournalists and tourists that occasionally shoot video for Web or home use, and these are larger markets for Canon than the filmmaking community.

One more new offering this year from Canon of interest to indie filmmakers is the Rebel T2i. Released in February at a price of around $900, this camera accepts interchangeable lenses, shoots 30, 25 and 24 frames per second at 1080p plus 60 and 50 fps at 720p. The T2i uses the same APS-C sensor as on the 7D.

NIKON

The camera that Nikon has released recently that will most likely impress HD filmmakers is the D3S. Out since October of 2009, it sells for around $5,000 but is equipped with a much larger sensor than the similarly priced Canon 1D. At 23.9 x 36mm the D3S sensor is actually a millimeter larger than a 35mm film frame as well as the full-size sensor in the Canon 5D. It is about twice the size as the sensor in Nikon’s first HDSLR, the D90. The larger sensor size gives Nikon a slight edge over Canon and Panasonic in extreme low light conditions when one would need to shoot higher than 6400 ISO. But this is decidedly a special effects look of use mainly to wildlife videographers and people like private investigators not shooting a theatrical feature.

The D3S has other improvements over the D90 that will please Internet videographers especially. Getting good quality sound onto the same card in the camera that’s recording the video has been a problem for both Nikon and Canon, but an external mic can be plugged directly into the D3S allowing stereo sound to be recorded. For narrative filmmakers, dual system sound is preferable anyway, but this is a great feature for grabbing an interview to put online or recording something like auditions. And the D3S also has an in-camera editing (i.e. trimming) function. Videographers on deadline will like being able to quickly shorten clips for relevant content before posting them on the Internet.

But what will continue to keep the Nikon from being as popular as the Canon 7D with filmmakers is its insistence on making HD available only in 720p. While still an excellent HD image, 720p just does not have the clarity of detail that 1080p offers. It’s close, but psychologically most filmmakers want that full HD if their work is ever going to appear on a 60-foot screen.

The fatal blow as far as Nikon ever dominating the filmmaking market is that the D3S has chosen to record in MJPEG rather than the codecs used by Canon and Panasonic (H264 and AVCHD respectively). MJPEG offer a slightly more degraded image than those codecs. This is great when you’re loading video onto a computer or streaming on the Internet (it’s faster because MJPEG is a smaller, more compressed file), but the price for this is loss of data. When it comes to HD video, Nikon seems to be aimed at photo-journalists and experimental filmmakers that shoot video for the Internet. And for that, I guess they could use a Flip.

VIDEOGRAPHY FOR THE WEB

If the cameras discussed so far are still more expensive than some budgets can handle, in addition to the Rebel T2i there were three new large-sensor cameras able to shoot HD with interchangeable lenses introduced this year that are worth looking into. The first is the Panasonic DMC-GF1, which retails for $800 and records in either AVDHC Lite or MJPEG. It shoots in 720p at 60 frames per second in AVDHC Lite and 30 fps in Motion JPEG. The other two cameras of interest to filmmakers whose work is not going beyond the Web sell for around $700. They are the Olympus EP1 and Samsung’s NX-10. All three cameras are getting excellent reviews from techie websites.

The Olympus and the Panasonic use a micro four-thirds sensor. Although the Olympus shoots true 1080p HD at 30 frames per second, it only does so on MJPEG. Samsung’s NX-10 shoots 720p in H264 and on an APS-C sensor which is slightly larger than the four-thirds system and only slightly smaller than the sensor on cameras that cost two or three times as much.

WHAT’S NEXT

These are thrilling times. For the first time in motion picture history there is a seamless “intercuttable” loop between a relatively inexpensive, portable consumer camera and professional, theatrical, high-end film or video systems. Film technology was never able to do this. The use of 8mm or 16mm film in 35mm productions was reserved for special effects sequences, scenes set in the past, delusions or dreams because consumer stock looked so grainy and contrasty compared to 35mm. HDSLR technology means people making movies on HD for theatrical release do not necessarily need large quantities of money to attain a big-budget look. What would El Mariachi or The Brothers McMullen look like if made today? What would those movies have cost?

But we’re still waiting for that HDSLR hit. The most successful high-profile use of these cameras has for the most part been with large productions that have full camera crews and a solid post department just standing by for data to be delivered. Andrew Disney, who just wrapped his full-length feature, Searching for Sonny, has this to say: “The DSLR is the reason I was able to make [my] movie. With the Canon 5D, I was able to create a spec trailer, a proof of concept, that looked superprofessional and filmic while costing very little. After I made the spec trailer, I found producers who saw potential, investors who wanted to back it, casting directors who wanted to cast it, and eventually actors who loved the script. The DSLR-shot trailer became my pitch, and it opened many doors. Almost too many. The project that I originally thought would be shot sort of guerrilla-style with friends became bigger than I ever imagined. We started getting names attached. Many of them joined not just because they loved the script, but also because they saw the [DSLR] spec-trailer. But then a funny thing happened. We started seeing some of the pitfalls of shooting [a feature-length narrative film] with a DSLR.”

Although the Canon DSLR was still very useful on second-unit and as a second camera, Disney’s feature was ultimately shot on a RED ONE. “As awesome as the footage looks [with a DSLR], what you see is what you get. There’s not much changing in post. Once we started asking the questions about DSLR, we instinctively looked at the RED. The freedom with white balance and color temperature became alluring. The ability to shoot RAW sounded pretty intoxicating. [And then] there’s the jelly effect — still a problem, especially when you want to shoot with longer lenses.” Monitoring at 480i doesn’t help either since the cameras can’t output at 1080 or even 720 when recording.

Richard Ulivella, who has worked with RED ONEs on features and Canons on commercials as a d.p. and gaffer agrees for the most part. “The best part of these cameras is that they are the size and shape of an SLR,” he says. “Ironically, it’s also the worst part. But they should be used for their strengths. If you routinely build them out to twice their weight and triple their size just rent a full-sized camera.” Ulivella feels that as amazing as the image achievable with an HDSLR is, the cameras are still best suited for commercials, documentaries, and as “eyemos” or B cameras. For now, shooting a whole feature with a HDSLR is doable but remains difficult. These cameras have achieved a secure position as a tool to be used for specific types of shots and sequences and as affordable cameras by cinematographers conscientious enough to test and plan for all the applications they will be asking of them and knowledgeable of what is going to happen to the image in post. The more things change, the more they remain the same. There is still no substitute for careful planning.