Back to selection

Back to selection

“If 1.33 is Confining, This Will Really Give You What You’re After”: DP Jarin Blaschke on The Lighthouse

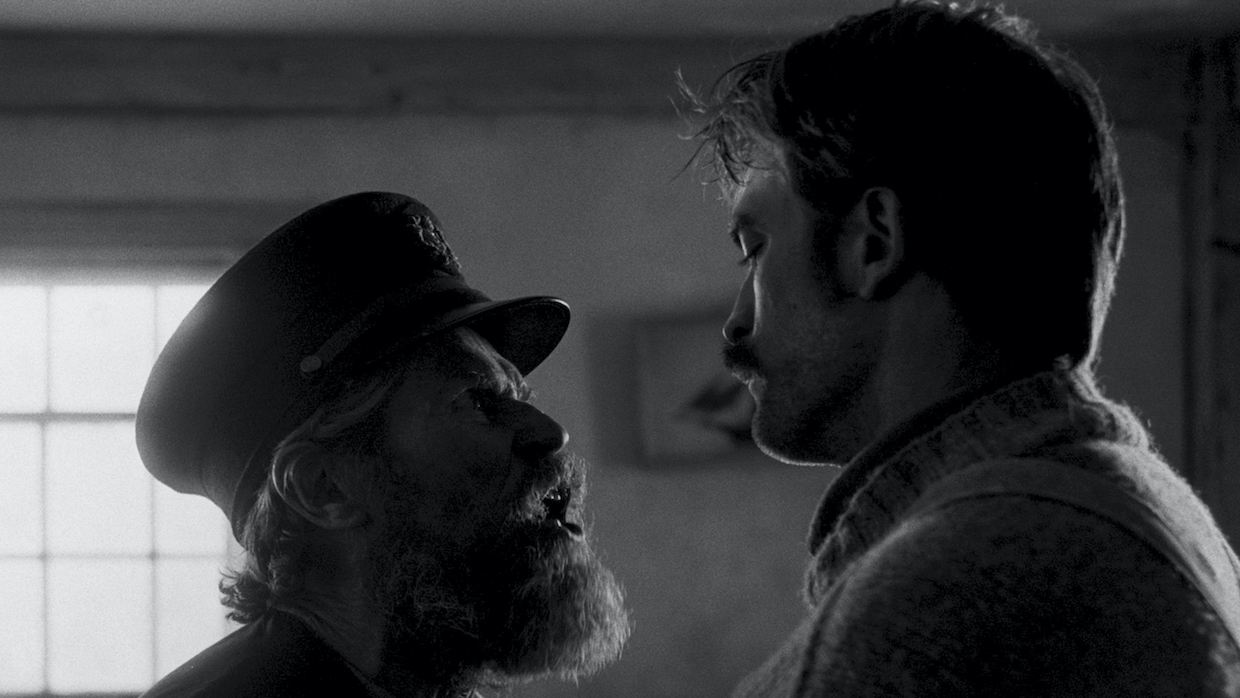

Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson in The Lighthouse

Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson in The Lighthouse Cut off from civilization, two lighthouse keepers fight the elements and themselves in The Lighthouse, a period drama directed by Robert Eggers and written by Eggers and his brother Max. Starring Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson, the film premiered in the Directors’ Fortnight section of the 2019 Cannes Film Festival.

Cinematographer Jarin Blaschke shot Eggers’s previous feature, The Witch (2015), as well as the Eggers shorts The Tell-Tale Heart (2008) and Brothers (2015). The Lighthouse was filmed in Nova Scotia in black-and-white and a 1:1.19 aspect ratio. It screened in the Debut Cinematographers series at Camerimage, the International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography, held this year in Toruń, Poland. Blaschke spoke with Filmmaker after the sold-out screening.

Filmmaker: When did the idea for The Lighthouse start?

Blaschke: I know Robert—we’ve been friends for over ten years. He pitched me the idea about three years ago. He first works on atmosphere. I’ll often get a lookbook, or at least a small library of images, before the script. This is very helpful, because you can get the subconscious started on ideas much earlier than otherwise, so things can come out at their own pace, [then] you can edit them down and make them as strong as possible. I didn’t have a script until a month or two before prep, but I had the overall look locked down for a couple years. We’re kind of finding our language together. It’s just dumb luck that we met and happen to see things in a similar way, or at least our version of translating the chaos of life into film.

Filmmaker: Did he share any visual references with you?

Blashcke: Robert showed me his favorite example of our aspect ratio, a German film set in mineshafts, Kameradschaft (1931). There were 20 to 30 films on a list he sent me for various reasons. Of those, Fritz Lang’s M was the strongest use of camera in a film. But the texture of The Lighthouse is more influenced by photography.

Filmmaker: The costumes, the windswept island, the ocean and boats reminded me of Winslow Homer’s work in Maine. One of the characters is even named Winslow.

If I was influenced by anything, it’s probably a lot of early modernist photography. Edward Weston is the one who got me into photography when I was 15, so that is just coursing through me really—I can’t help it. Then you’ve got his son Brett, you’ve got Imogen Cunningham, Paul Strand, all of those. I’m not trying to replicate their work, but I can’t help the proximate effect of some of my oldest friends.

Filmmaker: Were you always planning black-and-white and this aspect ratio?

Blaschke: It was always something similar. The frame was originally 1.33, because that’s what you think of when you think of a boxy aspect ratio. I think 1.19 just popped into my head one day, again because I had the pitch so early. If I hadn’t known about The Lighthouse until two months before we shot it, maybe the subconscious wouldn’t have had time to throw that idea at me. A year or so before prep, probably six months before I even had a script, I threw the idea at Rob of using 1.19. I thought, “Hey, if 1.33 is confining, this will really give you what you’re after.” I wasn’t really serious because it’s kind of a weird idea, but he took to it.

Filmmaker: What’s the creative effect of using a frame like that?

Blaschke: It begins as a feeling, but then you start to think about it and it makes sense. It’s about being stuck with somebody you can’t get away from, so you’re shrinking down the world as much as possible. Even in the blocking, you have to cram people together into the frame. They’re closer in the film than they would be in real life, but you don’t think about it because there’s no more frame. You’re not feeling the rest of the room.

Filmmaker: Is this the aspect used in early Fox sound features like Sunrise?

Blaschke: Technically it is, but it’s also the same thing as an anamorphic gate. You can actually get a ground glass for it pretty easily. You just use an anamorphic ground glass without the anamorphics.

Filmmaker: Does that frame affect how you move the camera?

Blaschke: I don’t know. I’m sure it does, but it didn’t feel like it. When I’m designing a dolly move, my process is to find a beginning frame, find key frames within the move, go from one careful frame to the next,and settle on something that’s strong, hopefully. I think that’s true whatever the shape of the frame is. If you have a boxy frame, you just find a composition that works within that frame.

Filmmaker: In those dollies I kept trying to see around corners, outside the frame.

Blaschke: You’re going to see it when we want you to see it.

Filmmaker: Did you have any pushback about using black-and-white film?

Blaschke: It was something we fought for. The studio people were responsible: they asked us if we had to do it this way. We gently insisted.

Filmmaker: Was it difficult to get Double X film stock?

Blaschke: Not terribly. Double X is available, just not hundreds of thousands of feet, which is what we needed. At least we knew the stock we were getting was fresh, so that was an advantage. Kodak needs about a six-week lead time. We gave our first estimate, saw how much we were using and somewhere in the middle of the shoot we put in another order which we hoped they would get to us before we ran out of the first batch.

Filmmaker: So you’ve chosen the aspect ratio, and to use black-and-white film. How did you decide on lenses?

Blaschke: When I was a kid I was obsessed with time machines. I would watch Back to the Future every weekend—we had it on VHS, my dad taped it off HBO for me. I was obsessed with time travel. Any time travel was going to do it. When you get older that translates into physical travel, because that’s the only thing available to you. But in movies you can travel through time. That’s the only way I know how to do it. Yes, you can travel to places in the world where it’s like going to another era, I’m also fascinated with that, and addicted to it. That all goes to say that when we make a film we really want you there, make you feel like you’re there. With this film I was trying to find a way to transport the audience photographically, and a lot of that was through optics.

Filmmaker: You wanted an optical equivalent of the 1880s?

Blaschke: Not literally, but something that just felt like you’re somewhere else. If the lenses get too crappy, it’s just kitschy. It couldn’t be too gauzey, but you wanted to transport people to that time.

Filmmaker: So you didn’t want the imperfections of period lenses?

Blaschke: You want some, but the right ones. That’s what all the testing’s about—finding the right characteristics and level that isn’t a distracting, flat effect, just enough to become that window to another world.

On The Witch we used older lenses, but I wanted to try lenses I hadn’t used before. I went to Panavision and asked for stuff I didn’t know about. What do you have that isn’t in your catalogue? They have all kinds of stuff, I’m sure I ended up seeing only a portion of it. Of what they showed me, the lenses I really fell in love are called Baltars, made by Bausch & Lomb. They were designed in the 1930s, so we’re not being literal, they weren’t built in the nineteenth century. They’re really tiny, it’s a simple optical design built before coatings were perfected and allowed for the more elaborate lens designs we have today. At the time you had to have a simple optical design, because too many elements without coating lowers too much contrast. all the light’s getting scattered in there.

The Baltars were single-coated, probably just the front element, so you had to be careful with flares especially. So the result is, the windows in the interiors have a little glow around them. I would spot meter to be very specific about how bright the bright window was. You couldn’t just let it go because then your image is out of control, it’s just going to be soup. So I had to do tests: at what point does a window of a certain size become too bright for the lens and film stock to handle? The windows in The Lighthouse glow a little bit, but it’s highly controlled.

We did have a couple of lenses based on nineteenth-century optical designs. They were newly made, but built following formulas from the late nineteenth century. There’s this design called the Petzval lens, by Josef Maximilian Petzval. It was the first fast portrait lens, which helped with portrait sitting times, the lengths of exposures. The Petzval lens has a very strong look. Especially when you get to the corners, it gets very swirly. We only used it for the most heightened moments, like having sex with the mermaid.

Filmmaker: At the screening you said you had filters made for The Lighthouse.

Blaschke: I’m probably not the first one to have this idea, but I had Schneider make a filter to my specifications. I drew a chart of what wavelengths of light I wanted to pass and which I wanted to block completely. They made it, which was something I didn’t know a manufacturer would do for a client. Panavision paid for them and then we rented them from Panavision. This is amazing to me because I don’t know who else is ever going to have a use for them.

Filmmaker; What are the effects from the filter?

Blaschke: It’s completely opaque to red light. This bag actually is a pretty good example, it’s pretty dark but this part would be white. These fish would be really white, these eyes would be almost black, these variations in red would be more defined between a darker grey and a lighter grey. It’s only sensitive to short wavelengths, emulating the primary emulsion type used until the late 1920s. Even further back, in the 19th century, it was even less sensitive: only ultraviolet and blue. Photographs of the time, the sky is washed out, just completely clipped white skies. Pictures from the Civil War, all the skin tones are really dark.

Filmmaker: You didn’t need a blue sky in The Lighthouse.

Blaschke: There are sunny days in the earlier part of the movie, where clearly you’d have a beautiful rich sky, but the sky’s blown out anyway. We probably annihilated some pretty clouds with that filter. What’s interesting is that the filter tends to reduce overall contrast, which you can bring back in printing. At the same time, the filter also emphasizes what you call local contrast, texture basically. The tones within someone’s hand or a small area of the frame will show more variation. But overall, your blacks are weaker, so you print with higher contrast to get them back, which then gives you even more micro-contrast. Whereas with a red filter it’s opposite. It smooths everything out, but overall the macro contrast is higher.

Filmmaker: What’s the speed for Double X?

Blaschke: Kodak says it’s 250 daylight, but I was pulling it for subtle reasons which I think are worth it. I pulled it a half-stop, which brings it down to 160 as far as what I saw on my meter. The filter takes about a stop down from that, so then you’re down to 80. The Alexa’s at 800, so it’s a ten-to-one difference in light levels. But if you have halogen, that’s similar to tungsten, proportionately with a lot more red light. So it’s less friendly to the filter. A greater proportion of what the bulb is putting out is stuff the film can’t see through that filter. So then you’re even further down at 50. So, we stuck to HMI lighting whenever we could. Ideally you want a higher color-temperature light just because it’s more efficient to pass through the filter.

Filmmaker: So you’ve got a lot of light.

Blaschke: Yeah, a lot. The set was very bright, 200 footcandles. It didn’t look anything like the movie. I read somewhere where they mentioned the “natural light cinematography in The Lighthouse” and I thought, “You’re way off.”

Filmmaker: How much of The Lighthouse was filmed on location, and how much on sets?

Blaschke: About fifty-fifty. The studio was in Halifax, I think it was an old printing press. On certain sets we knew where the camera had to go. We needed room for a crane, for example. For the interior of the lighthouse we had to find a very tall place. We ended up in this super dirty, toxic space. I don’t know what they made in there. You were afraid to step anywhere in case you would impale your foot on something. They had cleared it out generally, but there were giant divots in the floor. The way it looked, they could have driven tanks over it for 47 years.

Filmmaker: It didn’t look like there was a lot of room at their dining table.

Blaschke: It was moderately tight. It’s not like the apartments I had to shoot in when I was 25 years old. It’s a balance of big enough to shoot in but small enough to look small. It’s, of course, much easier to shrink a set visually than to expand it. The dining table was originally broader, I had to convince them to make it smaller. We used a director’s finder and round paper cut-outs to work it out.

Some of those scenes are on location, but only the night stuff. Except for one shot which didn’t make it into the final film, the day interiors are all on stage. You can do a better job because it’s all bounced light. If you put those frames outside, and you’re working inside and the wind picks up…anytime you don’t need big grip frames up on that location, the better it is.

Filmmaker: Your shots have to be designed so carefully.

Blaschke: Yeah, there are marks for everything. With dolly shots I’ll set frames through a finder, tell the crew “The track will go here, here’s one, here’s two, here’s three.” I’ll go do something else. When I come back, if the track’s a couple of inches off, we’ll adjust it. Craig Stewart, the key grip, was amazing. He had the same enthusiasm for getting it just right.

Filmmaker: How’s that for the actors? For instance, Dafoe has those long speeches, curses, imprecations.

Blaschke: He gives those standing up, he’s not generally walking around. He’s totally committed to the role. Rob’s great too. He’s doing this really crazy performance, but if you tell him to turn, open up to the camera on the next take, turn just a little bit one way or the other, he’ll do it.

Filmmaker: You’re working from a shot list? Do you block during rehearsals?

Blaschke: That’s somewhat true. There are things you have in your imagination, but you’re watching animation in your head. You need to see the real thing. You need to see the performance, the tone of the performance, to really devise the best shots. Some stuff needs adjusting. They want to lay down a certain way, Willem on Rob’s chest instead of his shoulder—that then necessitates being in a certain corner, and we’re going to block it over there. You have to adjust these things. But the basic idea is there. And then some shots are just so complex that you really do need to walk around with the actors on the actual set. That’s what rehearsal time’s for. I think in my mind the process was more flexible than they felt it was.

Filmmaker: Is there a different discipline on set with film versus digital?

Blaschke: The first two weeks people are adjusting, for sure. People are saying “Roll camera” before everything’s really ready. But after a while, it’s, “Come on, get in line here, take it more seriously.”

Filmmaker: Did that extend to the actors and how many takes they would do?

Blaschke: With the really hard stuff, you can’t put actors through some of the things we had to put them through. The least we could do was get our shit together. For the scene where Willem Dafoe is being buried, we did only three takes. How many times can we bury him? We’re at the monitor and the camera’s getting closer and the dirt is in his eyes. Rob and I are leaning in—it’s only a shitty video tap—and we’re biting our nails, watching: Oh my god is this going to work, is he going to get the whole thing? We did lose one take because it was too windy [for] the crane. It was just a bad shot. We had to wait for the wind to subside. And he’s laying in this frigid water that’s collected in the grave, waiting for the wind to die down.

I don’t know if anyone else notices that he’s chewing the dirt, which is kind of funny. You can’t use real dirt, you use cookie crumbs instead. So he’s eating cookies. We ended up using the last take, so hopefully Willem’s extra misery was worth it.

Filmmaker: What lab did you use?

Blaschke: Good old FotoKem.

Filmmaker: How did you view the dailies?

Blaschke: They send a link to a super-compressed file on a server. So you can check: did the camera move work? Is there a boom pole in the shot? Does the basic lighting idea work? That’s kind of it. Even issues of critical focus, you had to wait until the editor [Louise Ford] got the less compressed file. That was I don’t know how many days later. We were lucky to have Lou there. On the weekend I’d go to the editing room and we’d all hang out and look at stuff.

Filmmaker: Not much margin for error.

We’d wait for the dailies before we moved out of a location. We did move on to Halifax, but they didn’t destroy the set until we got all the dailies back. I kind of like that constraint, making strong decisions and not getting distracted. I do have a version of ADHD and in film I want to pare down decisions. I love getting rid of options.

Filmmaker: The Lighthouse probably has more special effects than I realize.

Blaschke: The logs, for sure, in the beginning, and then the last scene. We have a shot after Rob kills the gull. We cut and pan ominously over to the lighthouse, then go up the lighthouse. The move has a little wiggle because it’s a cable car—I kind of like that imperfection actually. When you get to the top and you’re passing a panorama of glass, you see the camera, of course, so they’re painting it out later. It’s not an open ocean in the distance, it’s actually a bay. You can see the local town across the bay, so that’s another effect. Almost all of the effects are stuff like that. There was a local lighthouse, we shot around it as much as we could. But I think there are one or two shots where the camera had to face the local and, they’ll have to forgive me, ugly lighthouse.

There was a trained gull. We shot that six months later in color, with a green screen. We emulated natural light by shooting inside a giant white bubble we made. I’m not 100% happy with the composite shot, only because you can’t quite match anything to look like black and white film.

Filmmaker: What were the shooting conditions like?

Blaschke: The weather was bad. It added four days to the production. It would be so windy the Technocrane was waving around, so we couldn’t use it. The breakfast tent put you in the mood for the day. I have a lot of memories of eating cold porridge in the morning. It’s rattling all over the place, clinking and clanking, rings hitting cable, you don’t know if the wall’s going to tear open. It was not good. And then you go out and it’s freezing rain. But we slept in a very cozy bed and breakfast, with a parlor piano.