Back to selection

Back to selection

Canon Reformation (2): New Commercials, 12 Monkeys, Mysterious Skin

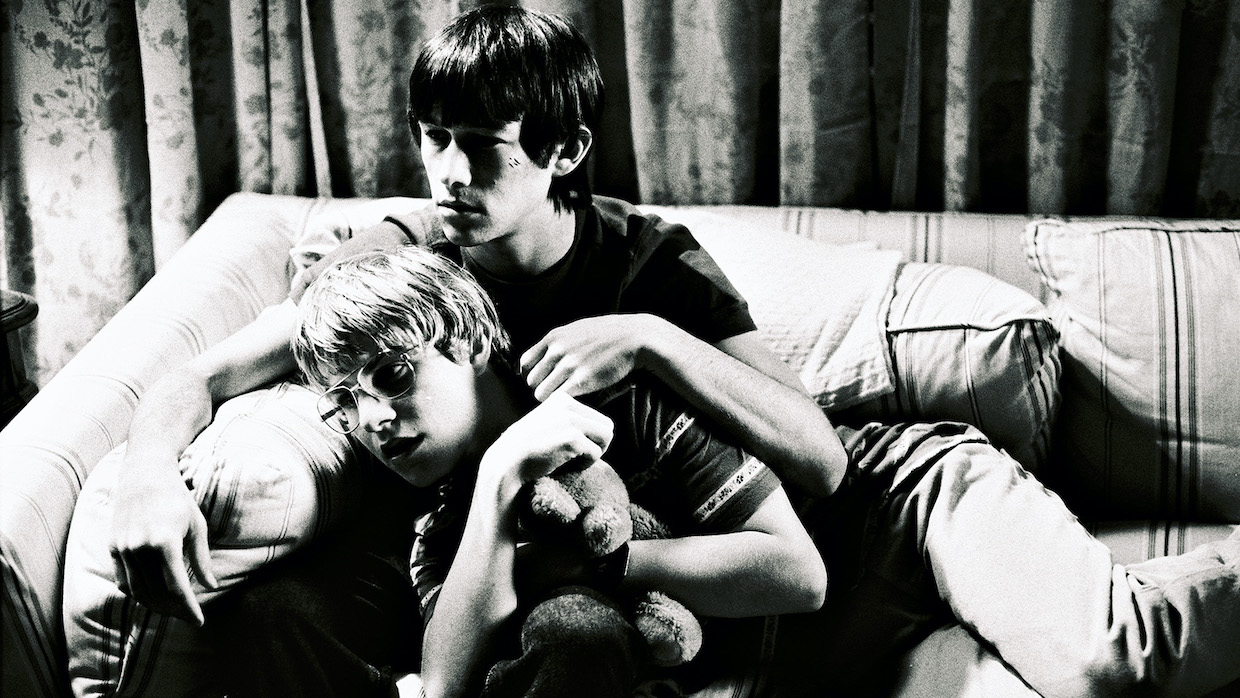

Brady Corbet and Joseph Gordon-Levitt in Mysterious Skin

Brady Corbet and Joseph Gordon-Levitt in Mysterious Skin Along with getting re-accustomed to watching movies at home, I’m also relearning the rhythms of having TV in my life on a regular basis, which hasn’t been the case for a good while. My preferred choice for some daily structure and accompanying info drip is local news via two easily streamable options, ABC and CBS. The former’s preferable because they almost never cut away to, or acknowledge, the daily presidential press conference. Anchor Bill Ritter was temporarily home with COVID-19 before returning to the studio, while weatherman Lee Goldberg was for a while doing the forecast from what looked like his parlor. Station bumpers repeatedly assure viewers we’re going to make it through this—as a warm voice insists, together.

Lysol’s ads haven’t been updated, nor those for pharmaceutical medication. With the option to shoot new footage with actors off the table for now, cutting together commercials that Speak To The Moment for other market categories requires ingenuity. One government PSA I’ve seen a lot starts with archival photos of the Greatest Generation, reminds younger viewers of their sacrifice, then asks us to do the same by staying home—to illustrate, stock shot of a vaguely sullen/confused looking dude sitting on the kitchen floor staring at his phone. Much stranger is Burger King’s new campaign, in which a man orders delivery Whoppers from a couch that floats upright as he salutes the front-line delivery worker. “Your country needs you to stay on your couch and order in,” says the voiceover. “Do your part. Staying home doesn’t just make us all safer, it makes you a couch potatriot.” It seems impossible this oddly specific footage could have been shot beforehand, but evidently it was—last fall, for a different concept (but what?!) that didn’t work out. “Staying on your couch has almost become an act of patriotism in these times, as well as a celebration of healthcare workers,” per Gabriel Schmitt of ad agency FCB New York. “Coincidentally, the assets fit these premises perfectly.”

People aren’t mandatory for car commercials, for which impersonal drone footage of trucks on dusty trails et al. will do just fine. Toyota’s nonetheless taken that extra human leap in phase two of its new campaign, getting longtime spokes-character “Jan” (Laurel Coppock) to tape messaging from home for two spots called “Toyota is Here to Help.” These are kind of flat and low-key, which is preferable to Fiat Chrysler’s overtly inspirational tactics. Their latest effort’s backgrounded by “Better Days,” a new track from OneRepublic (“Oh, I know that there’ll be better days/Oh, that sunshine ’bout to come my way”), with a voiceover that’s grave, solemn and incredibly cynical once you listen to what it’s actually saying:

Together, we can do this. Our spirit is what unites us. It is what bonds us and reminds us we are all one. Which is why if you need a vehicle during this time, we’re offering zero-percent financing for 84 months with no payments for 90 days and the ability to shop from the safety of your home. Better days are ahead.

In 12 Monkeys, TVs are often in the background but there’s no comparable messaging airing, just an ad for Florida Keys tourism—a cruel joke considering the earth’s entire surviving population is confined below ground for the indefinite future. (If consumer spending is down, who’s making those ad buys anyway?) It’s understandable digital rentals of 12 Monkeys have soared, but watching it right now is a less morbid/nervous-making proposition than Contagion, not least because the premise is that five billion people died in a pandemic—a number so far beyond what we’re looking at that there’s immediately distance. I didn’t see it during initial release, but way after, during a chronological push through the Terry Gilliam filmography in high school. Austin’s (just permanently closed) Vulcan Video maintained, per best video store practices, a “Director’s Wall” separate from the action, comedy, etc. sections. (“Foreign” directors were relegated to their own country’s sections, which is probably not worth getting up in retroactive arms about.) The sequential Gilliam binge was part of a short-lived, self-imposed initiative to work through directors’ filmographies in chronological order, though I only made it through two. The exercise immediately started to seem like an especially oppressive way to spend too much extended time in one person’s head—although, in retrospect, I didn’t help anything by marathoning Gilliam and Eisenstein, two filmmakers whose bombast can never be tuned out.

Brazil is clearly Gilliam’s most important/iconic film, perfect for 15-year-olds getting their cinematic feet wet: no subtleties to miss, bone-deep anti-authoritarianism rendered in shock and awe visuals. (I mean all this nicely.) It’s also virtually unwatchable in a theater, loud and unrelenting—Gilliam is one of the few filmmakers whose work benefits from scaled-down home viewing, where that excess energy is less exhausting. After his ’80s trilogy of increasingly expensive independence (Time Bandits, Brazil, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen), Gilliam tried to rehabilitate his troubled-production reputation with for-hire auteur glosses on previously-developed material. 12 Monkeys is most disciplined and best movie (not that those two qualities necessarily correlate as a rule), one which forced him to make uncharacteristic decisions.

Still, using the backhanded compliment of forced compromise seems needlessly rude: much of 12 Monkeys is surprisingly textbook/effective classical filmmaking that doesn’t feel made under duress. There are many scenes where the only real option is shot/reverse shot variants. Gilliam nails these, as in a long drive where Bruce Willis and Madeline Stowe hit the road from Baltimore to Philadelphia, without trying to jazz up actor-dependent exchanges through e.g. some characteristic canted/mirror distorted angles close up under either’s face. On the opposite end of the stylistic spectrum, there’s a closing-stretch epic crane down to young Bruce Willis in the airport parking lot. Gilliam explained on the commentary track (I used to listen to those!) that he didn’t want to film that shot at all, finding it narratively unnecessary and silly. In an effort to get it off the schedule, he demanded two cranes on top of the other, figuring the producers would balk. They surprised him by getting the equipment, so he had to go through with it, and his spite produced one of the film’s best shots. Sometimes it all works!

12 Monkeys is, in a meaningful sense, a remake of La Jetée, but it’s more focused on Vertigo, about which it’s not particularly subtle. After Willis and Stowe put on their disguises, they sit in a rep theater and watch it, issuing the thunderously banal (but true!) observation that every time you rewatch a film, “You aren’t the same person who saw the movie before.” Gilliam takes this logic a few steps further by refashioning the material into deliberate visual echoes of his own cinematic past: the opening (mildly annoying) sequences of Willis in the underground apocalypse are Brazil fully and self-consciously revisited on equally claustrophobic “exterior” sets cut off from all natural light. Katherine Helmond’s face-stretching surgery is restaged with a particularly unflattering shot of one of 12 Monkeys‘ female scientists distorted through a screen, and both films have significant setpieces in similar-looking expensive retail stores—one nightmarishly full, the other post-apocalyptically empty. This all builds to Stowe putting on the necessary blond wig, which makes her look not just like Kim Novak, but also Kim Greist in Brazil. (The two Kims!)

I also recently watched The Green Fog (streaming free here [EDIT: it’s back to password-locked, sorry]), Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson and Galen Johnson’s exercise in “remaking” Vertigo by stitching together analogous sequences from other films with nearly all dialogue removed. It’s useful for codifying the proposition that Vertigo is one of the Primal Myths of Pure Cinema, the source from which so many other have since drawn that gets at something essential about lonely viewers and their often uncomfortable gaze—Gilliam’s riff is probably my favorite. The structure is both tricky (things happening in the “present” cause reactions in the “future,” the order of cause and effect repeatedly changing) and intuitive: it’s fairly uninterested in laying out rules for time travel, instead propelled by a fatalism that, for the right kind of viewer (definitely me), is weirdly romantic. It was always going to be like this, and that final moment of deadly clarity is soothing in its inevitability, Melancholia without the really heavy devastation.

I’d never seen Gregg Araki’s work before Mysterious Skin came out, so the night before seeing it I rented The Doom Generation (RIP Vulcan, again) to get a little context. (Wasn’t my speed, though it was disorienting/enlightening to see James Duval, who I only knew from Donnie Darko, in his original, very different context of coming up as a core Araki player.) The image that got stuck in my head wasn’t from one of the traumatic sexual violations structuring the narrative, but a shot of vintage, c. 1981-era glass 7-Up bottles being shot with BB guns—the first time I recognized a specific case of period production design, appreciated the effort and wondered what it took to make it happen. In retrospect, this seems like a weirdly, prematurely hardened reaction: the first time I realized Mysterious Skin could actually be upsetting was a summer later, when I tried to show it to a friend who, halfway through, got freaked out and asked me to turn it off. Only now do I really get that.

Part of the reason I wasn’t fazed, I suppose, is because Mysterious Skin wasn’t “sexually explicit” relative to such contemporary, “boundary-pushing” releases as the unsimulated low-fi sex of Nine Songs or the considerably glossier The Dreamers, with its featured attraction of Michael Pitt’s penis as part of another attempt to reclaim the NC-17 for respectability. I was ID’d three times when I went to see that: buying the ticket, going into the auditorium itself, again when coming back from the bathroom. Everything’s either implied or, finally, described in Mysterious Skin, but not shown in detail, which would have been an impossibility in any case—you simply cannot film children in these situations, and Araki came up with strategies to make the adolescent performers respond to different fictitious scenarios rather than the actual plot. This is both responsible and, in an abstract way, kind of chilling, mirroring the false memories of alien abduction Brady Corbet’s character creates in response to foundational trauma, defense mechanisms that paper over what actually happened.

Mysterious Skin tracks two young men a decade after pre-pubescent sexual experiences with their Little League coach. Neil, who grows up to be Joseph Gordon-Levitt, is groomed into a procurer role; as a teenager, he starts turning tricks on his small Kansas town’s playground, graduating to NYC bars after high school. Bryan (Corbet as an adult) is much more nervous and skittish, staying home with his mom and prone to inexplicable nosebleeds. One reading is that both young boys are traumatized by their encounter but process it in different ways: Neil sublimates by throwing himself into increasingly dangerous sexual situations that culminate in a brutal assault, while Bryan chases false memories. There’s another, good deal more uncomfortable way to read the film: two young boys have formative sexual experiences at an illegal age, but with different results. Neil discovers his sexual identity early, choosing agency and self-actualization through sex work, while there’s no question Bryan is traumatized. This line of thought (further developed here by M Kitchell) is not likely to make anyone terribly comfortable. I’m not so sure about that latter interpretation now, which did occur to me when I first saw it.

Araki makes everything deceptively enjoyable to watch, especially because his repeatedly manifested desire to live in a world eternally soundtracked by shoegaze is expanded here by Robin Guthrie/Harold Budd’s pretty lovely score. Initially the first shot registers as out-of-focus lines of pure color: in focus, they’re brightly colored pieces of cereal falling onto young Neil’s head. The image looks like it’s out of a commercial, but a really good one—brightly and beautifully colored enough to be alluring rather than hack. The kids-on-bikes suburban look’s in the same nearly-literal neighborhood as E.T. (or the E.T.-imprinted Donnie Darko, come to think of it), the tension between the implication of youthful trauma and the pleasing reconstruction of its surroundings so evident that it doesn’t need to be explicated until the very end, which I’d forgotten for fairly good reason. It’s an extended duologue with intercut flashbacks filmed in a living room set with extremely theatrical lighting, not so different from a televised staging of, say, Tennessee Williams. No matter how queer the gaze behind the camera, this final scene’s a throwback now: two (very good) straight actors doing their darnedest, barreling through an extended series of revelations that pauses regularly for carefully timed sobbing, emotionally completely defined in a way the rest of the movie isn’t. Before then, the 1981 Araki reconstructs for the boys’s childhood years is consistently sunny and alluring, with a degree of period nostalgia baked in through vintage production design that doubles (inadvertently or not) as product placement. The assumption is that at some point, these two things (all those mini-cereal boxes poured on Neil included) became the same in an increasingly homogenized landscape, which seems about right.