Back to selection

Back to selection

Speculations

by Joanne McNeil

Quarantines and Future Dreams

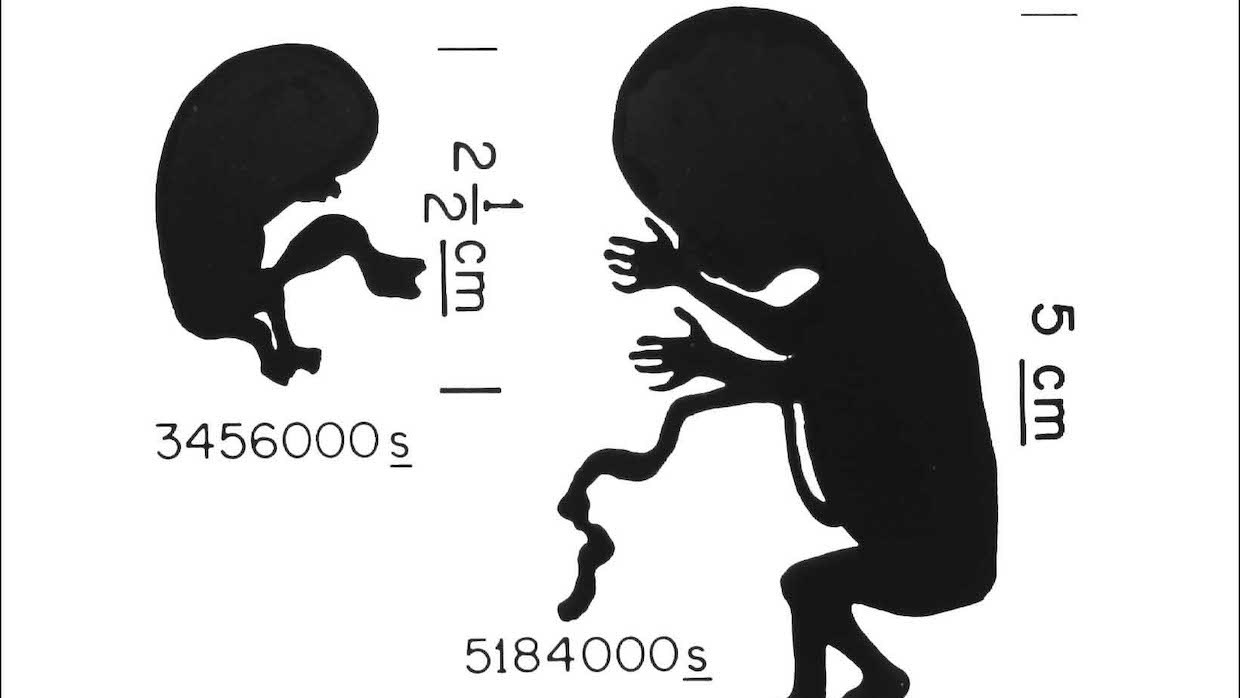

Jon Lomberg’s diagram of a fetus, included as part of the Voyager Golden Record

Jon Lomberg’s diagram of a fetus, included as part of the Voyager Golden Record Contact—yes, the 1997 Robert Zemeckis blockbuster—isn’t about a pandemic. It’s not celebrating an anniversary year or set for rerelease, nor is it a stone classic like Alien. But this moment of quarantines and uncertainty makes for an excellent time to revisit it.

What feels rare about the movie is its depiction of solitude rather than loneliness. I suppose this is true of many astronauts on the screen, but this one is unique because Ellie Arroway—the main character—experiences solitude continuously; it is more than just her journey in the third act. Actor Jodie Foster is routinely alone in the film, in a way that is self-contained and rather pleasant. She’s alone in hotel rooms or driving out to the canyons to sit by herself and think. She has been, unwittingly, preparing her whole life for the “machine seat”—the gateway for a single passenger who will enter, and presumably be transported to meet with the unknown extraterrestrial life. It is their messages that she has intercepted. Their instructions provide the wherewithal to build this mysterious vehicle.

Contact is not all quiet scenes of reflection, but those are the most striking images. Before Ellie receives the extraterrestrials’ messages, she waits for them. Or waits for nothing—which is another possibility. She works on a SETI (search for extraterrestrial intelligence) initiative at the Very Large Array and often waits, alone, listening to headphones for hours at a time, amid its towering radio telescopes. It’s a movie about solitude and patience.

While we are all forced to wait for something unknown on the horizon—a vaccine, a weaker strain of COVID-19 or further calamity—Ellie’s patience is soothing to watch. And at a time when a visit to the movie theater feels as unlikely as a journey into space, the scenario feels as plausible as any. If aliens were to reach out to us tomorrow, would it even register among the top 10 weirdest things to happen in 2020?

As a first contact story, Contact is a bit unusual. The terms are more ethical than science fiction is used to: No one is colonizing anyone or under occupation. The connection with extraterrestrials is peaceful and consensual. Humanity goes because we were invited. The film is based on Carl Sagan’s novel, which began as a screenplay he worked on with Ann Druyan. Fiction that begins as a film project often tends toward exposition and clunky language, but Sagan’s 1985 novel is well written, with heartfelt passages about the potential of the night sky and Ellie a fully realized character. Before working on Contact, Sagan was the chair of the Voyager Golden Record, compiling sounds of various cultures, life and nature on earth onto two phonograph records sent into space in 1977, with the hope that someone unknown might capture and decode this work one day. Some of today’s wildly popular fiction, like Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem and Ted Chiang’s short stories, expand on these ideas, and similar questions are asked in novels like Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow and work by Stanisław Lem. It seems natural to be drawn to this literature these days. How could aliens be any worse than the fascists and incompetent leaders here on earth? Maybe if we got in touch, humanity might get on its best behavior for the others. But first, they’d have to invite us.

Contact is also about the chaos that unravels after the news gets out about the alien messages. There are clashing earthbound agendas about what to make of this encounter and how to approach the unknown, including whether Ellie is suited as a representative of humanity, given that her atheism puts her in a minority. It’s the case of every new frontier: People with the best and worst intentions rival for a piece of it.

Last year was the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11. This year is the 50th anniversary of Gil Scott-Heron’s spoken-word poem response to it: “Whitey on the Moon.” (“I can’t pay no doctor bills, but whitey’s on the moon. Ten years from now I’ll be payin’ still, while whitey’s on the moon.”) This trivia was often repeated in media coverage of the SpaceX launch on May 30th, four days after protests began in Minneapolis in response to the senseless killing of George Floyd by a White police officer. The president and vice president attended the Cape Canaveral spectacle with SpaceX founder Elon Musk. It was the first time American astronauts have traveled to space from a domestic launch since the retirement of NASA’s Space Shuttle program in 2011. It was also the first time humans have traveled to space on a spacecraft developed by a private company. “The flight comes at a time when people are clamoring for good news amid the COVID-19 pandemic, surging unemployment and growing U.S. protests against police violence,” said a report from Bloomberg News. But in a matter of days, good news emanated from these protests in promising fits and starts. A Sheraton hotel in Minneapolis was briefly commandeered and transformed into a sanctuary and shelter for the unhoused. Six blocks in Seattle as of now comprise the “Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone” (CHAZ). An estimated 15,000 people gathered near the Brooklyn Museum for a rally in support of Black trans lives. The Minneapolis City Council voted unanimously to change its city charter, as a first step to replace its police department with an as of yet unannounced community-oriented “transformative new model.” The inertia and fear that set in early in the quarantine has given way to modest and unpresumptuous feelings of jubilation. There’s a sense this summer that another world is possible, and it is happening on the ground.

Could we have predicted any of this even days before it happened? If we were to have Contact-like first contact anytime soon, those aliens would have a chance to see humanity at its very best: working toward solutions and finding hope in what once seemed like impossibly dismal circumstances.