Back to selection

Back to selection

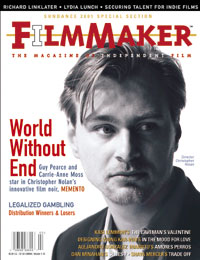

Past Imperfect: Christopher and Jonathan Nolan on Memory, Metaphysics and Memento

Memento (Photo by Danny Rothenberg)

Memento (Photo by Danny Rothenberg) The following interview with Christopher and Jonathan Nolan was originally published as the cover story of Filmmaker‘s Winter, 2001 issue.

As French film critic Andre Bazin might have once said: “Why don’t you take a picture? It’ll last longer.” Bazin, as some of you may remember from your Cinema Studies courses, was one of the progenitors of the auteur theory, the line of thinking in which directors are considered the kings of filmdom, and the aggregation of their personal style is seen as a map of their royal terrain. Bazin also liked to talk about film, philosophy, photography and death, even if he didn’t actually get around to putting them all together as succinctly as the statement above. Nor did he live long enough to review the funny, unnerving, and altogether puzzling Memento,writer/director/auteur Christopher Nolan’s entertainingly convoluted second feature. Too bad; it would have provided exactly the right context for the above-proffered quip.

Memento, after all, is a film about death, photography and the philosophy of going about everything backwards. Take the chronology of its plot, for example. A guy named Leonard – sucker? psycho? something in between? – is found holding a photograph in the very first shot, only something’s not quite right: that photo, a Polaroid snapshot of a dead man’s body, is in the process of fading from grisly red to tabula rasa white. Then, just as suddenly as it appeared, the image leaps from Leonard’s fingers and gets sucked back up into the camera from whence, just moments earlier, it came. There’s something wrongside round already, but what does any of it – the de-developed snapshot, the tattoos that cover Leonard’s body, or that creepy guy named Teddy (who looks suspiciously like Joe Pantoliano) – have to do with whoever might have murdered Leonard’s wife?

Turns out the guy’s full name is Leonard Shelby (he’s played by a bottle-blond Guy Pearce, the bad “good” cop from L.A. Confidential), and, well, you know what they say about trusting a man with two first names. (A woman, either, since The Matrix’s Carrie-Anne Moss is part of this confusion too.) Leonard can’t even trust himself, mainly because he doesn’t know himself: he’s afflicted with an unusual mental disorder that prohibits him from remembering the recent past, not even the past of 10 minutes ago.

He just keeps taking snapshots of people and places, and scribbling cryptic notes on them, hoping against hope that the pieces will some day all make sense. It doesn’t exactly help things, though, that Memento – a film that starts with its ending and keeps forever jumping back into the footprints it’s only just finished making – presents the world from Leonard’s own scrambled, self-erasing point of view.

Based on a short story by Nolan’s brother Jonathan (who, just for the sake of further conversation, likes to be called Jonah), Memento is part pulpy crime thriller, part metaphysical analysis of a world gone, as Leonard might put it, “[…]Uh, what were we talking about? I’m sorry, have I told you about my condition? I can’t make new memories. I can’t even remember to forget you.” Borrowing from the inherent confusions of film noir, Nolan’s film forces the viewer to question his characters, challenge their actions, and even begin to second guess themselves. If you find yourself watching the film and repeatedly stammering, “Now, wait a minute!,” don’t panic – you’re well on your way to winning the game.

Christopher Nolan’s no stranger to jigsaw narratives or put-the-pieces-together-as-you-go filmmaking: his first feature, Following, was shot over the course of a year, and it’s all about the ways one double cross tends to envelop the next. A double-crosser himself, Nolan – half-English, half-American – was inspired to make Following, which was shot entirely in England, by American no-budget independent cinema, and could only find distribution by bringing the film back here. With just these sorts of double-crossings in mind, Chuck Stephens sits down with the brothers Nolan, Chris and Jonah, to talk about the art of following Memento, the no-budget momentum of Following, and the bifurcating narrative paths that lead to the heart of their new-model film noir.

FILMMAKER: Both of your films use very inventive and unnerving formal structures, yet their stories are firmly grounded in one of the most familiar of genres, the film noir. How and why do they fit together?

CHRIS NOLAN: For me, film noir is one of the only genres where the concept of point of view is accepted as a fairly important notion in the storytelling, and where it’s totally accepted that you can flashback and flashforward and change points of view. The best film noir always involves a continuous reassessment of things, especially in terms of “Who’s the good guy?” and “Who’s the bad guy?” You want the double cross, you want the surprise, and you want to keep the audience mindful of the fact that they don’t know the full story, and that they can’t trust all the characters. So when Jonah told me the story he had for Memento, the idea of relating the condition this guy has – his inability to keep memories fixed in his head – in terms of a revenge scenario, it seemed like the most interesting thing to do would be to take the film-noir approach, and to tell the story almost entirely from that character’s point of view. His psychological condition and his point of view are crucial to why the structure is there: it’s an attempt to put the audience inside his head, and to make them think about the characters around him and the situations he’s in in the same way that he does.

FILMMAKER: So many independent films borrow material from film noir and crime fiction, and there has been, for many years now, a very definite sense of diminishing returns in that approach. One of the most interesting things about Memento is that you’ve deranged the narrative line so thoroughly that the viewer gets so caught up in putting the story together and the familiar pulpiness of the ingredients almost disappears.

C. NOLAN: If that’s true, that’s great, because I really wanted to use the structure of the movie as a way of reawakening some of the things that used to be so valued in the genre: the paranoia and exaggeration in our everyday insecurities. But the genre’s been used so many times, you have to try very hard to find new ways to energize it. If the audience goes into Memento expecting just another film noir, I think they’re going to be kind of disappointed, because it’s about more than that. Fortunately for us, our European distributors did an excellent job of not trying to sell the film that way.

FILMMAKER: The film’s already been released in France and England, right?

C. NOLAN: Yeah. There was always a kind of feeling that we should start in Europe with this film, and especially a sense that the French would really get the movie.

FILMMAKER: There is a certain European flavor to the film, a kind of implicit expectation that audiences will be willing to work to engage with a very active and nonlinear narrative.

C. NOLAN: Maybe, though I don’t see Memento as an art movie, and I’ll be very disappointed if it ends up being perceived that way. I think of myself as a pretty mainstream filmmaker, ultimately.

FILMMAKER: To what extent, if any, is Memento a kind of remake of Following, or at least an extension of similar ideas?

C. NOLAN: I think Memento’s really very different. But it’s also a very natural progression from Following, because it has some similarities in terms of structure. What I wasn’t able to do in Following, and what I was able to do with Memento, was to embrace the more immersive side of cinema – the atmospheric dimensions of what it was we were exploring. Following was very specifically just narratively driven. I think it has an interesting style, and I certainly did everything I could to shoot it in an interesting way, but we had to shoot in a very documentary style. With Memento, we were able to shoot anamorphic, to get a really crisp image, and to use a much different color palette, all of which helped to get across a level of mood and atmosphere that were denied us in Following. The sound mix in Memento makes a big difference too.

FILMMAKER: Jonah, how did the story that Memento’s based on first come to you?

JONATHAN NOLAN: The idea started to come to me while Chris was finishing up Following, at a point where I had taken a semester off from college, and was doing some traveling. I had read about this condition in one of my General Psych classes, and I already had a number of different things that I knew I wanted to deal with in a story, ideas about identity and memory. I was at a period in my life when I was thinking a lot about victimization; about what being victimized does to people, and how they recover and learn to get over it. One of the things you find yourself doing in that period of recovery, once the initial aura of the incident fades, is willing yourself to remember the incident. In some cases, obviously, people are flooded with memories, and they can’t escape them, but I was more interested in situations where people force themselves to remember the bad things that happened. I got very interested in the idea of a character who was stuck in that moment.

FILMMAKER: Is there a clinical term for Leonard’s condition?

J. NOLAN: It’s generally known as “anterograde amnesia,” as opposed to retrograde amnesia, which is the standard plot device where you get hit on the head and you don’t know who you are. Anterograde amnesia is where you have difficulty remembering things from both the time before the inciting incident and after. Obviously, I was using this psychological condition as a metaphorical device, and not to mount any sort of sincere investigation of what it would be like to suffer from it. Hopefully the story’s not too out of bounds or unrealistic in terms of the actual nature of the condition. I wanted to use the condition as a metaphorical way of dealing with some philosophical questions without being overly philosophical in doing so. What I wanted to do with it, in metaphorical terms, was to explore the nature of memory, and especially the idea of manufactured memories; of memories that seem to be completely vivid, yet may only be a fiction that’s built of stories one has heard and pieced together over a lifetime. Part of it may stem from my relation with Chris, brother to brother, where the older brother is always telling the younger one stories that may be true, or may just be ever more embellished and misleading versions of some truth. One of the standard things in film-noir is the idea that you can always come back, at the end, to the idea of truth with a capital T, and I really wanted to get away from that.

FILMMAKER: Did you publish the story, and did the story differ significantly from the way it takes place in the film?

J. NOLAN: I hadn’t completely finished writing the story when I first told Chris about it, which was while we were driving across country, from Chicago to L.A. The story kind of became the film during that drive, and I never published it. In a way, though, the Web site I designed for the film [www.otnemem.com] is a fusion of ideas from both the story and the film.

FILMMAKER: I’ve only had a chance to see Memento once, and maybe this question would be answered by a second viewing, but I’m wondering if, when pieced together, the story actually does all add up in a plausible way?

C. NOLAN: I think it does, but it would be unreasonable to expect the audience to get it all the first time. And I wanted to allow for a certain amount of room for interpretation. It’s all in there, though, if you have the time to watch it twice. But the film doesn’t explicitly identify what that objective truth is, because that would betray the notion that we want to stay inside this character’s head who can’t ever connect with an objective reality. Allowing for the sorts of improbabilities that exist in any film – exaggeration, melodrama, heightened emotions and so on – Memento does all fit together.

FILMMAKER: It’s interesting to think about the way that Leonard’s confusions and the viewer’s confusions are fused.

C. NOLAN: The most interesting part of that for me is that audiences seem very unwilling to believe the stuff that Teddy [Pantoliano] says at the end – and yet why? I think it’s because people have spent the entire film looking at Leonard’s photograph of Teddy, with the caption: “Don’t believe his lies.” That image really stays in people’s heads, and they still prefer to trust that image even after we make it very clear that Leonard’s visual recollection is completely questionable. It was quite surprising, and it wasn’t planned. What was always planned was that we don’t ever step completely outside Leonard’s head, and that we keep the audience in that interpretive mode of trying to analyze what they want to believe or not. For me, the crux of the movie is that the one guy who might actually be the authority on the truth of what happened is played by Joe Pantoliano [The Matrix, Bound], who is so untrustworthy, especially given the baggage he carries in from his other movies: he’s already seen by audiences as this character actor who’s always unreliable. I find it very frightening, really, the level of uncertainty and malevolence Joe brings to the film.

FILMMAKER: Speaking of Pantoliano and the film’s recurrent photographs, I loved the line he tosses off when Leonard snaps his Polaroid: “Nice shot, Liebowitz.”

C. NOLAN: [Laughs.] Yes, that was one of Joe’s ad libs. We did a lot of rehearsals at Joe’s house with him and Guy, and I ended up adopting a lot of the material that was developed there. Many of the jokes came from Joe, and I think my favorite may have been the one where he asks Guy “What are you, Sherlock Holmes, or Pocahontas?”

FILMMAKER: The film also seems to make the most of Carrie-Anne Moss, particularly in the way that casting her and Pantoliano reinforces certain similarities that Mementoseems to have with The Matrix.

C. NOLAN: Carrie-Anne and I discussed the relationship Memento has with certain ideas from The Matrix in the sense that both films deal with the subjective nature of reality, though in very different ways. The thing that first attracted me to Carrie-Anne, though, was that when I saw her in The Matrix, I thought she had these two sides to her that were exactly what I was after. This strong, armored way of coming across, and also the way she could, at times, really open up and reveal a more gentle side as well.

FILMMAKER: And Guy Pearce?

C. NOLAN: I had seen Guy in L.A. Confidential and Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, but I had never really put it together that I was looking at the same actor. Once I did, I knew that an actor who could so fully inhabit both of those parts could probably do anything he set his mind to. One of the best things Guy ended up bringing to the project was [his] really logical mind. He would question me on every aspect of his character’s behavior. That helped us tighten the ways Leonard deals with his predicament. Guy’s also got a refreshing lack of vanity, and a real desire to reinvent himself for every role.

FILMMAKER: Certain aspects of Memento’s structure reminded me of writers like Borges and Cortazar. Were there literary figures — or other filmmakers — that had an influence on your thinking about storytelling.

C. NOLAN: I’m a particular fan of Graham Swift’s novel Waterland, which deals with parallel time lines, and the way past history, recent history, and the present keep running in and out of sync. Nicolas Roeg, who’s a very experimental filmmaker working within a mainstream context, is a filmmaker I really enjoy, Performanceespecially. There’s a not very well-known Sidney Lumet film called The Offense, with Sean Connery, that I quite like, and — though I have to admit that I’ve only just recently seen it for the first time — John Boorman’s Point Blank is filled with identity issues surrounding the main character that are just fantastic.

FILMMAKER: Hmm. Lumet’s an American, though he made The Offense in England; Boorman’s English, but Point Blank is an American film. There seems to be a pattern here …

C. NOLAN: [Grins.] Yeah, well, I’m half American and half English, and I’ve always been interested in making films in both places. In America certain elements of different cities are very homogenized: the endless freeway culture, gas stations and motels, [and these] are essential to Memento because, by their nature, they represent a certain sense of anonymity. I felt this story really needed a large American landscape, a place where somebody could truly get lost. The bits between the airport and downtown in American cities always really intrigue me, because you can’t really tell what part of America you’re in, except maybe by the names of the grocery stores. It wouldn’t be the same at all in England: the idiosyncrasies of the way people talk give away in an instant where you are at any particular time. Memento seems like such a specifically American kind of story.

FILMMAKER: It’s interesting that Memento was made in America and released in Europe first, whereas Following was shot in England, but released in the States first.

C. NOLAN: Different markets are good for different things. With a no-budget movie like Following, there was already such an acceptance of those kinds of movies here in America, and a much greater tradition of just getting out and making your own movie. Following was made entirely in England, and is very much an English film, but for me, the way it got started was a very American one. I’d been in America and I’d seen people making films for no money, the Robert Rodriguez’s of the world, and at that time in England, it was a very weird thing to do. People were very much like, “Why are you doing this?” and “What are you going to do with your film when it’s finished?” Here it’s kind of accepted that if you’ve got a story to tell, you just find a way to do it. Ironically, at the time, low-budget English films were actually pretty high budget, typically around a million pounds. Nobody was doing the $6,000 movie there.

FILMMAKER: You did all the camera operation on Following, right?

C. NOLAN: Yeah, it was all shot in 16mm with an old Arri BL, all handheld. We didn’t have any video assist, so I kind of had to shoot it myself to know what I was getting. And while I was processing the footage as we went, I wasn’t syncing it up with the sound, so I shot for like six months before I saw and heard the elements together, which, when I think back now, seems a little bit crazy. I sort of had to trust my instincts, which in the long run seemed a useful discipline, because you have to think about whether you’re really getting what you need when you’re there with the actors. On Memento I did the same sort of thing, in that I didn’t look at the video monitor very much. I preferred to concentrate on the actors, and to look at them from the side of the camera, which apparently directors don’t do that often anymore. I didn’t use a headset that much either, because I prefer to listen to the way things are coming across live. In the headphones, the sound is compressed, and the voices sound much more energetic and powerful than they do when you’re actually there, and you can be quite disappointed when you don’t hear it that way once you’re in the Avid room. So you sort of learn a few things on low-budget films that you can apply when you move to slightly higher budget.

FILMMAKER: Can you characterize the kind of budget jump you made in going from Following to Memento?

C. NOLAN: The easiest way to put it is just to say it was a jump from thousands to millions.

FILMMAKER: Any idea what you want to do next?

C. NOLAN: [Laughs.] Yeah — make that same kind of jump again, from millions to billions. See, I told you I’m really a very mainstream filmmaker at heart!