Back to selection

Back to selection

“Can a Psychopathic Institution Be Redeemed, or Should It Be Eliminated?”: Joel Bakan and Jennifer Abbott on Their TIFF-Premiering Doc The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel

The New Corporation

The New Corporation I can still recall my red pill moment while watching Jennifer Abbott and Mark Achbar’s 2003 documentary The Corporation with my best friend, at the (pre-financial crisis) time an analyst at a big bank. “Corporations are people? What the hell?” I practically shouted. “Yup,” he simply responded with a weary shrug. For many clueless progressives like myself, unaware that corporate power had been spreading like the coronavirus, silently hijacking all branches of our government for decades, The Corporation was both horror film and wakeup call. The real deep-state conspiracy.

Since then we’ve endured the Great Recession and our current economic calamity/health catastrophe/racial injustice awakening. Still, corporations continue to shrug. And follow a well-worn playbook: Break the government. Declare, as Reagan infamously put it, that ”Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem.” Then follow with the tired Trump line, “I alone can fix it.” Rinse and repeat.

Or rather, this time around, rebrand as “socially responsible,” uh, people. Which is where Joel Bakan (who wrote the 2003 doc, based on his book) and Jennifer Abbott’s The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel picks up. This indeed necessary film pulls back the curtain on a slew of sleight-of-hands, including the profit-making privatization of the public good, and how business as usual has been made easier ever since benevolently ruling the world became the new spin. Of course the original problem, as The Corporation so convincingly made the case for nearly two decades back, is that corporations also firmly fit the definition of psychopaths. Thus now we have green, woke psychopaths. Welcome to the Davos-sponsored Matrix.

Fortunately, Filmmaker was able to catch up with the Canada-based co-directors to discuss countering the do-gooding gaslighting and more prior to the film’s September 13th Toronto International Film Festival premiere.

Filmmaker: It’s been 17 years since the TIFF premiere of The Corporation, which Jennifer co-directed with Mark Achbar and edited, and which Joel wrote (and was based on his book). So how did this sequel come about — and why now, a dozen years after the financial crisis? Have you been in production this entire time?

Bakan: I began thinking about a sequel after the 10th anniversary screening of The Corporation. The original film and book challenged the corporation and its power over society. Yet after the film came out corporate power continued to expand. Corporate harms, like the 2008 crisis, continued to mount. And the larger crises we had looked at – climate crisis, democracy crisis, inequality crisis – were dangerously accelerating. Clearly the first film hadn’t done the trick.

At the same time, beginning around 2005, corporations had begun positioning themselves as the good guys – effectively saying (and some corporate types actually did say this to me), “We may have been psychopaths before, but now we’re better, or at least getting better.” And they leveraged that new image to gain even more power over society to the point where we went from a society that problematically contained corporations (as we documented in the first film) to one that is essentially contained by them.

I began mapping out a book about all of this in 2012 (which will be published this month by Penguin Random House), and in 2015 producer Trish Dolman suggested a film sequel. I wrote a detailed treatment. We secured funding. Then Trump was elected, bringing to a fine and dangerous point all the problems with corporate power. Jenn joined the production in 2017, and we were off to the races. (Though, as it turned out, more as a tortoise than a hare.)

Abbott: I didn’t even want to make the sequel! Having been one of the directors and the editor of the first film, the idea of wrestling another monster of a film like The Corporation to the ground terrified me. I cut the first film from 400 hours of footage, and by its release I was near collapse. And though the problems we explored in the first film have certainly intensified, much of our original critique stands.

I was also in the midst of making another film, The Magnitude of All Things, about ecological grief and climate change — which as it turns out is also currently being released. So I was fully occupied with that in addition to single parenting.

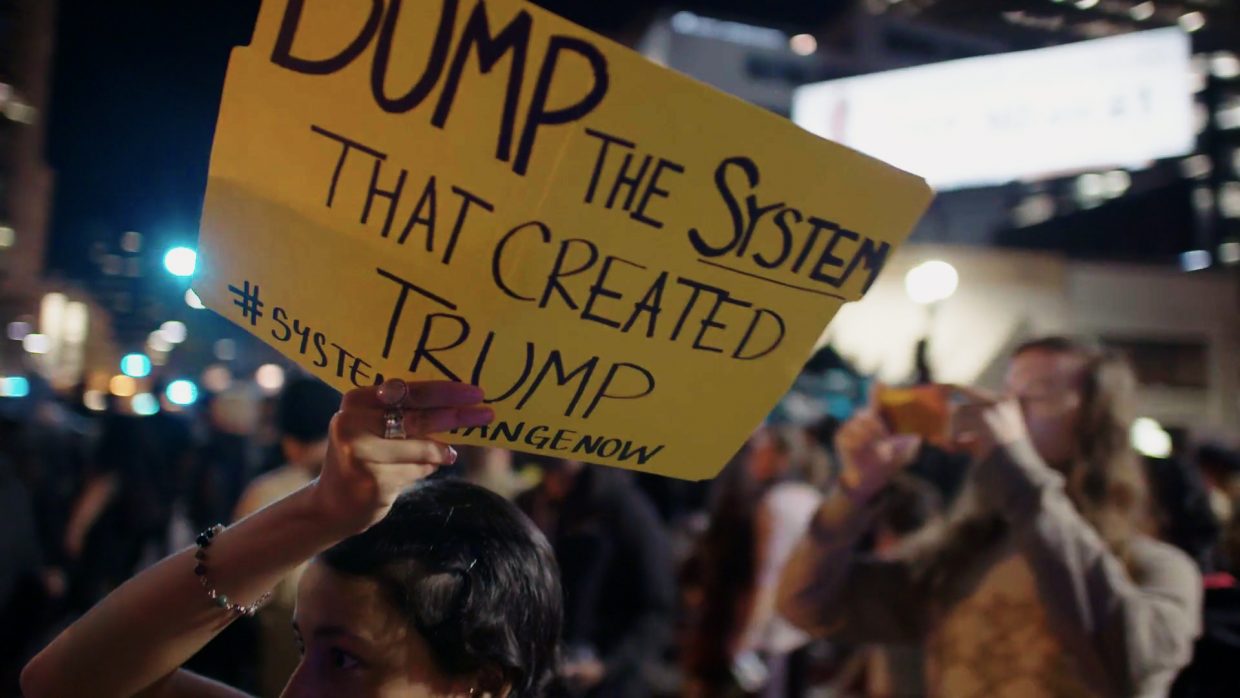

And then Donald Trump was elected. The veil came down. There was no longer even the pretense that governments and corporations were acting independently. With Trump’s election, everything got spat into the open; the system was rigged in favor of the plutocratic class, and now they were doing it in plain view. And although Trump is a symptom and not the cause of many of the crises we face today, suddenly for me the world was a different place and there were compelling reasons to make the sequel. So I joined the race. Or to riff off of Joel’s analogy, became one of the tortoises plodding tenaciously to the finish line.

Filmmaker: This sequel features a wealth of insightful thinkers, from writers to activists to politicians. So how did you decide who to include in the final cut? Was there anyone you reached out to but couldn’t get to go on camera?

Bakan: I had my wishlist of activists, politicians, intellectuals. They were in the original treatment, and most of them made it into the film. We would have loved to have gotten Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez but were unable to.

As for people from the business world, Davos was high on the list as it’s really the hub for the new kind of capitalism and corporation we critique. We were fortunate to be able to go there, and also to interview the events chief and organizer, economist Klaus Schwab. BP was also high on my list as it featured centrally in my first book (though not in the film), and we were able to interview former CEO Lord John Browne, which was great. Unilever and JP Morgan Chase were obvious since they and their CEOS are seen as leaders of the new corporation movement, and they also have a place in the film. We tried to get many others business leaders – especially of big tech companies – but for some reason they didn’t return our calls.

Abbott: I also had my wishlist of activists, politicians and intellectuals, some of whom we managed to interview and some not. Which is a good segue into some of the differences between making the sequel and making the first film.

For the first film, we managed to secure an interview with the late economist Milton Friedman early on. That opened doors to others in the corporate world. Of course, we were also new on the scene and with no reputation to precede us (at least not with the name The Corporation). Understandably, when we reached out to some corporate insiders for the second film, we frequently received radio silence.

But we managed to get interviews with some leading figures from the corporate world, and also other footage. The footage we use of Jamie Dimon, for example, speaks volumes as he is rendered speechless by Katie Porter, grilling him about the low wages JP Morgan Chase pays its employees. We also filmed at Davos. And certainly many leading thinkers and activists did accept our invitation to participate, and shine in their eloquence.

Filmmaker: One of the most memorable shots in the film depicts graffiti on a wall that reads, “Corona is the virus. Capitalism is the pandemic.” Which made me wonder how our collective global nightmare has affected the film. Did the pandemic disrupt production or influence the edit? Is it impacting your post-TIFF release?

Abbott: Thankfully we had completed production and were deep into post when the pandemic hit. But because the pandemic relates so strongly to almost all of our film’s themes, to not include it risked rendering the sequel out of date even before its release.

And so, for the first of two times, we broke open picture lock to integrate not only the injustices Covid-19 laid bare, but also the way the pandemic showed us we were not merely the self-interested, consumerist individuals that corporate ideology defines us as. It was also so important to Joel and me that we include the relationship of zoonotic diseases like Covid-19 to the destruction of nature and abuse of nonhuman animals. The pandemic is a wakeup call to humanity. If corporate capitalism does not halt the destruction of nature and respect other species as sentient beings with inherent rights, more pandemics are on the way. And who knows with what virility.

Bakan: Yes, the film was essentially in the can when the pandemic hit Canada. Jenn and I — and also our brilliant editor Peter Roeck — felt strongly that we had to open the can, add to and recut the film. Our producers managed to find the time and resources, so that’s what we did.

It was challenging for sure. But at the same time, the way the pandemic unfolded hit just about every note we had previously developed in the film. It was really a remarkably poignant case study that touched on all of our key arguments. So we built pandemic content into the various sections of the film, and then created specific pandemic sections in both the diagnostic and prescriptive parts of the film. One of the things I’m most proud of is how we integrate return interviews from self-isolation with people who appeared in our original shoots.

Filmmaker: Another global development that’s occurred recently is the growing support of Black Lives Matter, which seems to me might pose one of the greatest existential threats to the corporation since it’s an anticapitalist movement at its core. So do you see the BLM-specific, socially responsible rebranding of corporations ultimately winning hearts and minds (and dollars)? Could any of BLM’s tactics actually potentially upend the corporate structure?

Abbott: Even though we had finished the film and were out of time and resources, we were insistent about including a section on the extraordinary and ongoing uprising after George Floyd’s brutal murder. We negotiated two weeks to do it and I believe its inclusion transformed the film.

The film’s narrative arc, and what I’ll call Act 2 in particular, plunges us into the despair of the existential crises we face today in large part due to the destructiveness of corporate capitalism. And then we feature resistance. But it was only with the passion, momentum and success of the BLM uprising to infiltrate the mainstream and effect systemic change that we were able to include a story with enough hope to match the despair of Act 2.

Suddenly, and I mean suddenly, the mainstream was questioning public allocation of funds to the police, military, schools and hospitals. Suddenly, the racist roots of capitalism in slavery and colonization are front and center in public discourse as colonial statues topple. Suddenly, the mainstream is admitting to the existence of systemic racism. And suddenly, because of the combination of both the pandemic and the uprising, the system itself is being challenged in a way I’ve not witnessed in my lifetime. So for me the inclusion of the uprising made our film, which is in effect a call to action, authentically hopeful.

Bakan: The film was, again, in the can when George Floyd was brutally killed by police, sparking the uprising that continues as we speak. This time we had really run out of time and resources, but again, we felt it was necessary to address this. As you point out, it really does pose an existential threat to the corporation (despite corporations’ saccharine and transparent attempts to position themselves as allies – further evidence of the “new” corporation).

We examine the uprising both as an indictment of the racialized inequality that corporate capitalism is built upon and continues to entrench, and also as an example of a remarkable movement that is not only revealing but profoundly challenging corporate capitalism’s intersecting racial and economic injustice. It’s a powerfully poignant and inspiring ending for the film.

Filmmaker: It’s also long been thought that corporate reform can come from increasing diversity in the board rooms and at the C-suite level. But if corporations are psychopathic, as your original film hypothesized, wouldn’t this just in practice be another glossy rebranding? Can a psychopath be redeemed, or should it just be eliminated entirely?

Bakan: The power of the analysis in both films (and in the corresponding books) is that they examine the corporation as an institution with a particular legal structure and set of imperatives. That legal structure has not changed for publicly-traded corporations even while various reforms have been made — like greater diversity on boards and management teams, better governance structures, and even legal license to consider non-shareholder interests (so long as they don’t interfere with shareholder interests).

None of those get at the core corporate imperative to prioritize over everything – including democracy, diversity, racial justice, human rights, climate, and the environment – the financial interests of shareholders. And that’s the fundamental problem, as we reveal in the film. In my book I analogize the corporation to ice hockey. Hockey is fundamentally a violent sport – speed, hard surfaces, and tenacious attempts to possess the puck and put it in the net lead, unavoidably, to violence. We can change some of the rules – ban head checks, no-touch icing, larger ice surface behind the net, etc., all of which potentially make the game safer. But it’s still hockey, and still violent. Some players and teams may play a less violent game, others a more violent game. But they’re still playing hockey.

It’s the same for the corporation game. There are fundamental rules that make a corporation a corporation within capitalist systems – mainly, that those who invest in a corporation are entitled to have their money used in their interests. If we change that rule we no longer have a capitalist corporation – and, in fact, we no longer have capitalism as we know it. That’s because corporations are integral to how industrial capitalism functions.

So it’s too simple to say, “Okay, let’s get rid of corporations,” or “Let’s reform corporations.” But neither is really the answer. The first won’t happen unless there is a broader systemic change to capitalism itself. And the latter may have some positive effects, but none that significantly change things. So our solution is to bolster democracy, to take it back from the corporate interests that have captured it, and make it work the way it’s supposed to – participatory, public-interest driven, justice-oriented, egalitarian, and a robust and true check on corporate power and impunity. Sometime in the future we may have a society that is something other than corporate capitalist. But in the meantime our best hope, and the best first step for getting there, is to re-enliven democratic citizenship and democracy itself so that governance is actually for and by the people — and sufficiently contains corporations to protect the public interest.

Abbott: Yes, I agree with everything Joel says on this subject, and credit Joel and his books for essential contributions to understanding the battle between corporations and democracy.

To add to that, even before Joel and I started working together almost 20 years ago now, we each independently had a fascination with “dereification” and “making the familiar strange.” In fact, every single one of my films has tried in some way to do this. And so with The (New) Corporation films – plural now! – one of our broadest objectives is to expose what seems “normal” and “natural” as being socially constructed.

While it seems to many like “just the way it is,” corporate capitalism came into being and is maintained through a series of deliberate and well-calculated decisions. If that’s the case, well, we can make different decisions. We can create different economic systems and different institutions. We can evolve. We can change. So to address your question directly, can a psychopathic institution be redeemed or should it be eliminated? My answer would be that through reflection, greater understanding and thoughtful action, we can create institutions and systems that are more equitable, more just, more compassionate and more livable. If our films open up some imaginative space to do that, then I’ll feel we’ve done something worthwhile.