Back to selection

Back to selection

Tennessee Johnson, I Spit on Your Grave and Adaptation: Jim Hemphill’s Home Video Recommendations

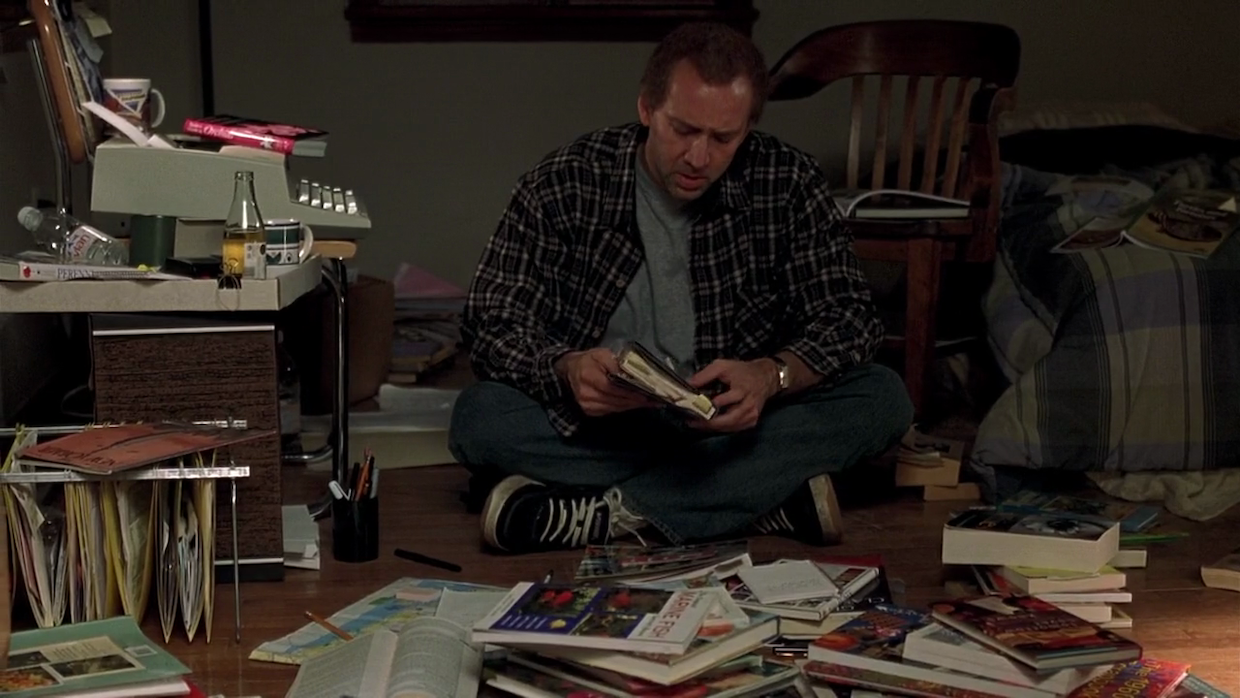

Nicolas Cage in Adaptation.

Nicolas Cage in Adaptation. These days, director William Dieterle is best remembered for his dreamy, stylized melodramas of the mid-to-late 1940s (I’ll Be Seeing You, Portrait of Jennie), but in his own time his greatest successes were mostly sturdy prestige biopics like The Story of Louis Pasteur and The Life of Emile Zola. A key transitional film was 1941’s The Devil and Daniel Webster, which introduced a supernatural element to Dieterle’s work and paved the way for a return to the German expressionist style in which he had worked as an actor. Before the delirious flights of fancy to come, however, Dieterle made one last return to historical biography and created one of his finest films with the 1942 drama Tennessee Johnson. The story of the rise and fall of Abraham Lincoln’s vice-president Andrew Johnson, the picture exhibits Dieterle’s finely tuned eye and ear for rural Americana; early scenes depicting Johnson’s rise from poverty-stricken tailor to U.S. senator are filled with illuminating details of language, gesture, and production design that belie the movie’s backlot origins. The film gets even better when it moves to Washington for a series of process-oriented sequences in which Dieterle squeezes all the drama that he can out of the Senate’s response to the Civil War and its aftermath. Questions relating to reconciliation vs. justice in a divided country are explored with verve and intelligence, and feel extremely prescient and relevant – Dieterle and screenwriters John L. Balderston and Wells Root had an understanding of something so central to American culture that the speeches in Tennessee Johnson feel like they could have been written in 2020. The film is also gorgeously photographed by the great Harold Rosson (The Wizard of Oz, Singin’ in the Rain), whose shimmering black-and-white images here are nearly the equal of his classic work on John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle. Rosson’s cinematography is beautifully preserved on Warner Archive’s new Blu-ray of Tennessee Johnson, which also contains some nifty classic shorts and other supplements.

A very different movie that nevertheless also speaks to 2020’s cultural divide in interesting ways is Meir Zarchi’s notorious 1978 horror film I Spit on Your Grave. Initially released as Day of the Woman before it was retitled and reissued in 1980 by exploitation impresario Jerry Gross (who also created a famous poster featuring the half-naked body of then model Demi Moore in the place of lead actress Camille Keaton), I Spit on Your Grave is a ruthlessly stripped down tale of rape and revenge so graphic that film critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert made a crusade out of trying to get it yanked from theatres. They argued that the movie was somehow an incitement to sexual violence, an assertion that seems mystifying given Zarchi’s clear identification with his heroine, unremittingly ugly portrayal of the rapists, and insistence on draining even the slightest hint of eroticism out of the picture. That said, it’s tough to blame Siskel and Ebert and Spit’s other detractors for letting the relentless brutality of the film overshadow its considerable virtues as both a harrowing condemnation of sexual assault and an allegory for red state/blue state tensions. As in many other rape-revenge movies (including John Boorman’s justly lauded Deliverance), there’s a great deal of class resentment simmering beneath the violent surface of this movie that, as Joe Bob Briggs has pointed out, is partly about the country’s antipathy toward the city and the city’s revenge against the country.

In 1980, Siskel and Ebert’s characterization of I Spit on Your Grave as morally reprehensible garbage stuck, and the movie was pulled from theatrical distribution before finding financial success in the home video market, where its infamy made it a hot VHS rental. Eventually I Spit on Your Grave was taken seriously by feminist film scholars like Carol Clover and Alexandra Heller-Nicholas who gave it more nuanced and constructive readings than earlier critics, and it’s now available as part of a superb deluxe Blu-ray package from Ronin Flix. The boxed set includes a pristine new transfer of the film as well as a Blu-ray of I Spit on Your Grave: Déjà vu, Zarchi’s ambitious 2019 sequel that amplifies and updates the first film’s sociopolitical subtext by pitting its heroine and her daughter against heavily armed religious zealots. A third disc contains Zarchi’s son Terry’s excellent documentary Growing Up with I Spit on Your Grave, and spread across all three discs are multiple supplements including a pair of great audio commentaries by Briggs. I would have to say that my “recommendation” here is somewhat more qualified than usual given the savagery of the films and the original’s still controversial reputation, but for those willing to wrestle with the ideological implications of these challenging movies the Ronin set is exquisitely produced and indispensable.

One movie I can recommend without reservation or hesitation is Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman’s brilliant Adaptation (2002), which is out in a new Blu-ray edition from Shout Factory via their “Shout Selects” label. The film was director Jonze and screenwriter Kaufman’s follow-up to their 1999 collaboration on Being John Malkovich, and it’s even more audacious and original – and thus even more impressive when the filmmakers pull off their cinematic high wire act. Adaptation began life when Kaufman took a writing assignment adapting Susan Orlean’s book The Orchid Thief and quickly realized that it was an unfilmable tome; instead of turning in a straight adaptation, Kaufman wrote a script about the impossibility of adapting the book, making himself and Orlean lead characters along with a fictional twin brother, Donald Kaufman. (Both Kaufmans are played by Nicholas Cage in one of his best performances.) The creation of Donald is one of Kaufman’s many truly inspired ideas, as the character allows him to look at screenwriting from both his (Charlie’s) point of view as a painfully insecure artist aspiring to greatness and from Donald’s perspective as a dilettante who strikes it big after taking one Robert McKee writing seminar. (Brian Cox playing the real-life McKee is yet another of the movie’s comic masterstrokes.) Kaufman uses the relationship between the brothers to explore, with hilarious and often agonizing accuracy, the neuroses and resentments that occupy so much of so many writers’ time, and goes on from there to skewer the movie industry as a whole with as much wit and anger as Robert Altman’s The Player.

Like The Player, Adaptation is a commentary on itself that has a lot of fun mocking screenwriting “rules” that it then proceeds to follow, albeit in very different ways from those espoused by McKee and his ilk. Yet while The Player is Hollywood satire from the point of view of an executive, Adaptation is from the point of view of a writer, and this is a key difference – it’s a lower to the ground perspective (one of the funnier running jokes in the movie is Kaufman’s near invisibility whenever he visits the Being John Malkovich set), and a more compassionate one. As in Being John Malkovich, a premise that starts off seeming like a self-reflexive comic gimmick develops into something far more, a philosophical inquiry into why and how we tell and consume stories and an examination of their role in helping us find purpose in our lives. The story of the Kaufmans runs parallel to and ultimately intersects with the heavily fictionalized story of Orlean writing her book and beyond, and although the movie threatens to collapse under the weight of all the narrative games Kaufman’s playing it never does; Jonze nimbly orchestrates the multiple levels on which the film is operating and pulls them together in a finale that’s as surprising in its purity and simplicity as it is overwhelming in its comic and emotional effects. This is a movie of infinite rewards that provides new satisfactions on every revisit, even if your repeat viewings number well into the double digits like mine.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently streaming on Amazon Prime and Tubi. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.