Back to selection

Back to selection

Sundance 2021 Critic’s Notebook 5 (Vadim Rizov): I Was a Simple Man, The Blazing World

I Was a Simple Man

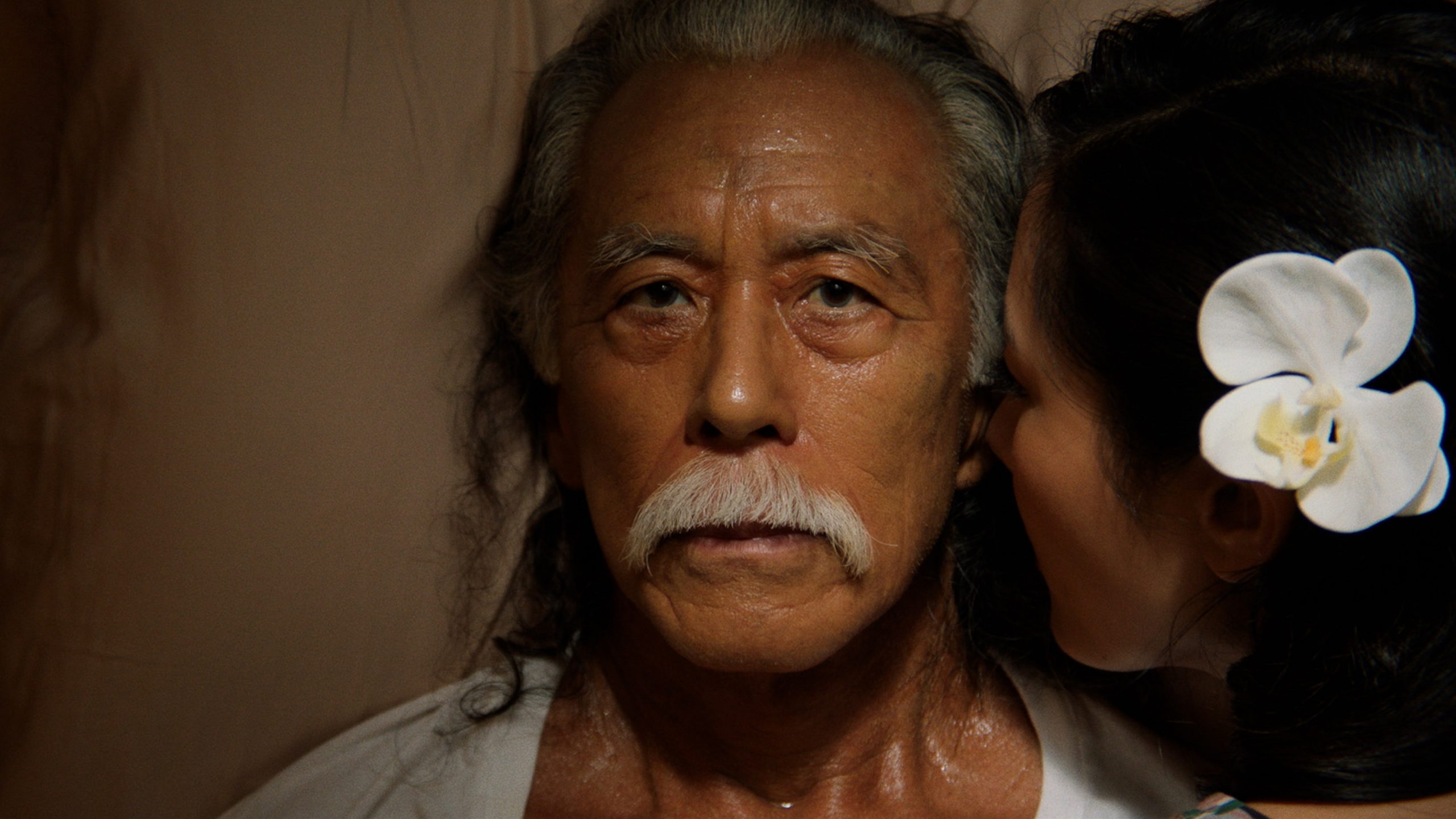

I Was a Simple Man Sundance 2021 offered two case studies in the anxiety of influence, or lack thereof—neither film’s particularly worried about covering its tracks. Hawai’ian director Christopher Makoto Yogi’s I Was a Simple Man is a logical progression from his first feature, 2018’s August at Akiko’s, which climaxed by layering a Mulholland Drive riff (a sax player soloing inside an empty cave with no audience) on top of Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (said shot of cave models its angle and lighting directly on Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s climactic setup). But August at Akiko’s told an essentially simple, literally meditative story about atmospherically re-immersing oneself at home after a long time away, grounding itself in the titular Akiko’s meditation facility and keeping story elements to a minimum. Simple Man’s much more ambitious in telling the story of Masao (played at his oldest by Steve Iwamoto, a non-performer who made his debut in Akiko’s). Now in his final days, Masao’s told by his doctor to quit smoking and drinking and is in need of care from children he long sent away. Straightforward enough, but Simple Man unfolds over three, non-linearly intercut time periods, flashing back to Masao’s life just after wife Grace’s death in 1959, and further back still to his teenage years.

Simple Man augments Akiko’s baseline gentle tone with tougher-minded, harder-to-effectively-strike notes: fear of death, late night terror in its imminent presence, reckoning with regrets stretching back 60 years. Its clumsiest gestures are when it explicitly enfolds history: placing Grace’s death in the year of Hawai’i’s statehood is allegorically understandable, but the name unfortunately reminded me of the metaphorical-and-literal title of the John-Cusack’s-wife-died-in-Iraq drama Grace is Gone (yes, both the person and concept have departed). Enfolding Chinese-Japanese animosity in Hawai’i, a healthy anti-colonialist streak and urban over-development among its topics, Simple Man is trying to explore a lot of ground with varying degrees of success. Its period dressing, which creates an effective spell that doesn’t feel under-resourced and which hides its low-budget canniness, is more sophisticated than the bluntly historical dialogue it sometimes supports.

Thematically overstuffed, Simple Man similarly covers a lot of stylistic terrain. Weerasethakul is a given (one of the last shots is like a mash-up of Blissfully Yours and 2001—no objection here!), while Tsai Ming-liang comes into explicit play in an near-end dream shot of Masao sitting in his ravaged living room at night, staring at the trees outside like Lee Kang-sheng contemplating the mountains-and-river wall mural at the end of Stray Dogs. (New Taiwanese Cinema draws upon the visual history of landscape scrolls; Yogi repurposes that visual frame of reference for a different topography.) Both Apichatpong and Tsai are referenced in the press kit, but there’s some other uncited names to throw in. Tarkovsky manifests twice, via both Stalker’s glass-moving-across-table, rendered more naturalistically, and a much smaller version of The Sacrifice’s climactic fire. David Lynch isn’t important visually but sonically: in the opening industrial roar of downtown Honolulu, screaming with construction screeching layered over what sounds like actual moaning slowed down to bass horror element, the dense nighttime soundscapes surrounding Masao’s house and the ominously compressed whooshing of traffic as heard from inside his car. Even John Huston is sourced; unless I’m wildly over-reading, a quick insert short of a bloody toilet bowl is modeled off a similar cut in Fat City (this is, very occasionally and judiciously, a painful accurate study in end-of-life care).

Yet I find Yogi’s invocations of Wong Kar-wai in a barfight between a grieving Masao and some random thugs (never seen before or after—memory is hazy!) particularly fascinating. Masao instigates and they pin him to the wall on at right; the camera pans with them, then starts drifting left to the opposite side as the fight’s heard continuing offscreen, panning over the variously indifferent and appalled faces of patrons before Masao and his opponents come crashing back into stage left, all to the strains of a melancholy ’60s soul deep cut. This is at once evocative, cost-effective and clear in its influence, and because of the Hawai’ian location and unfamiliar atmosphere/faces onscreen, Wong’s guiding spirit is transmuted into something new. Throughout, there’s the feeling of strong artistic inspirations being literally projected onto new landscapes and buildings; both the artistic idioms and locations come out transformed and stronger for the encounter. I can’t pretend Yogi’s New Taiwanese Cinema antecedents don’t make me more receptive (I love all this stuff too), but it’s very easy to get this idiom wrong. At certain moments, Yogi will detour entirely out of those languages into something lighter and unexpected, as when one of Masao’s grandchildren, who’s come to care for him, takes a break to go hand out at the local skaters’ parking lot of choice. He skates down with hardcore on his headphones, then hangs out in shots calmer and less portentous than much of the film—a small visual and tonal break, but still unexpected, welcome and heterogeneous. Two features in, Yogi’s still expanding his emotional and stylistic range for something that’s more often hypnotic than clumsy.

Carlton Young’s The Blazing World takes an entirely different approach to its influences. Expanding her 2018 short of the same name, Fort Worth native Young co-writes, directs and stars in one of Sundance’s pandemic features—shot in August, which presumably means Udo Kier flew out to Texas for the occasion. An opening prologue sets the would-be cult tone on one dreadful afternoon, as adolescent Margaret plays with her twin sister Elizabeth. Whisky-drunk dad Tom (Dermot Mulroney) is inside inflicting physical violence on mom Alice (Vinessa Shaw); outdoors, a CG crow slams itself into the side of the house before dropping dead, which is supposed to be freaky but is inadvertently hilarious, like Birdemic with the animation budget for precisely one avian. In all the excitement, Elizabeth drowns in the family pool while mesmerized Margaret stares at Kier, who gestures at her to enter some sort of black hole.

Cut to the present: before reluctantly heading home to see her parents, Margaret dreams of being drowned by Kier in a bathroom whose only window is a stained-glass church pane. This is about 15 minutes in, by which point it’s been clearly established that All Is Not As It Seems: Margaret gets her to-go donut bag delivered by a man who disappears after she turns her head, nobody seems to know what she’s talking about, reality is sliding in and out. I was pretty positive at this point we’d be getting the “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” ending, but that seemed too predictable so I stuck around to see which twist we’d land on. I should have known better after Margaret asks, in all sincerity, “What if there isn’t any bottom of the rabbit hole? What’s down there?”

At home, mom’s ominously twitchy and says things like (re: potentially cleaning her daughter’s room) “I didn’t want you to kill me or anything,” at which point I felt positively trolled into calling the ending way too early. Meanwhile, dad’s down in his mancave and getting smashed Texas-dad style, teeing off indoor golfballs while blasting “I Wanna Be Adored,” which must have taken a good chunk to license. Margaret, inevitably, goes down said rabbit hole, though this is less Alice in Wonderland than its much inferior gloss, Labyrinth, but for trauma. Once she’s leapt to the dream world, Margaret walks down Caligari hallways to find Kier again; turns out he’s a creature named Lained and sends her off on an explicitly archetypal quest. Retrieving four keys from various ogre types will help her recover her not-dead sister (aha!) from the netherworld, thereby assuaging Margaret’s crippling guilt and depression. The script is quite clear on this point, as it is on everything: walking through the ill-lit spooky lair, she makes sure to say that “The darkness is crushing me.” (I was kind of hoping for some dry ice smoke to go with the ‘80s vibe, but no such luck.)

At this point The Blazing World starts to resemble Ready Player One if the latter hadn’t, Overlook Hotel sequence aside, rendered its references as avatars and characters within an original (relatively, anyway) visual world of its own construction and instead made every single shot full-on pastiche. In a production design-minded way, Blazing is impressive, but to no end worth pursuing. On her quest, Margaret’s first dropped into a fantasy desert world to face off against her mom as a mask-wearing grotesque; the landscapes invoke Tarsem’s The Fall, the grotesquerie both his and Young’s antecedent Alejandro Jodorowsky. When Margaret re-enters her alternate-world home to face off against an equally grotesque sinister version of her dad, Isom Innis’s score immaculately recreates Wendy Carlos’s opening synth tones from The Shining; later, Margaret faces a pair of massive doors which open in ominous slow-(e)motion, releasing not a flood of blood but pure, cleansing and symbolic water. A climactic shot manages to simultaneously evoke Neon Demon (Margaret lying on a floor surrounded by neon lighting), Cube (turns out she’s lying in a…cube) and The Cell (that cube’s planted within a similarly Damien Hirst-y space), which is definitely a kind of referential hat trick.

As the parade of unacknowledged citations continued, I entertained the possibility that this was, on a subtextual level not at all articulated in the dialogue, visualizing what it’s like to process trauma through pop culture totems. But this is not a movie that leaves anything unarticulated, and by the time Bad Dad explains what he represents (“me, the harbinger of violence…and shame. Shame”), I had little choice but to take the film at absolute face and textual value. These influences aren’t transfigured beyond the sum of their parts, they’re just familiar window dressing for a story whose chosen ending is a version of “If you think really hard about your past and realize exactly who inflicted each source of damage, it’ll be well.” Naming things doesn’t lance wounds; far better to go to therapy and settle in for the multi-year haul.