Back to selection

Back to selection

“Looking At Diversity Through A Different Lens”: Debbie Lum on Try Harder!

Try Harder!

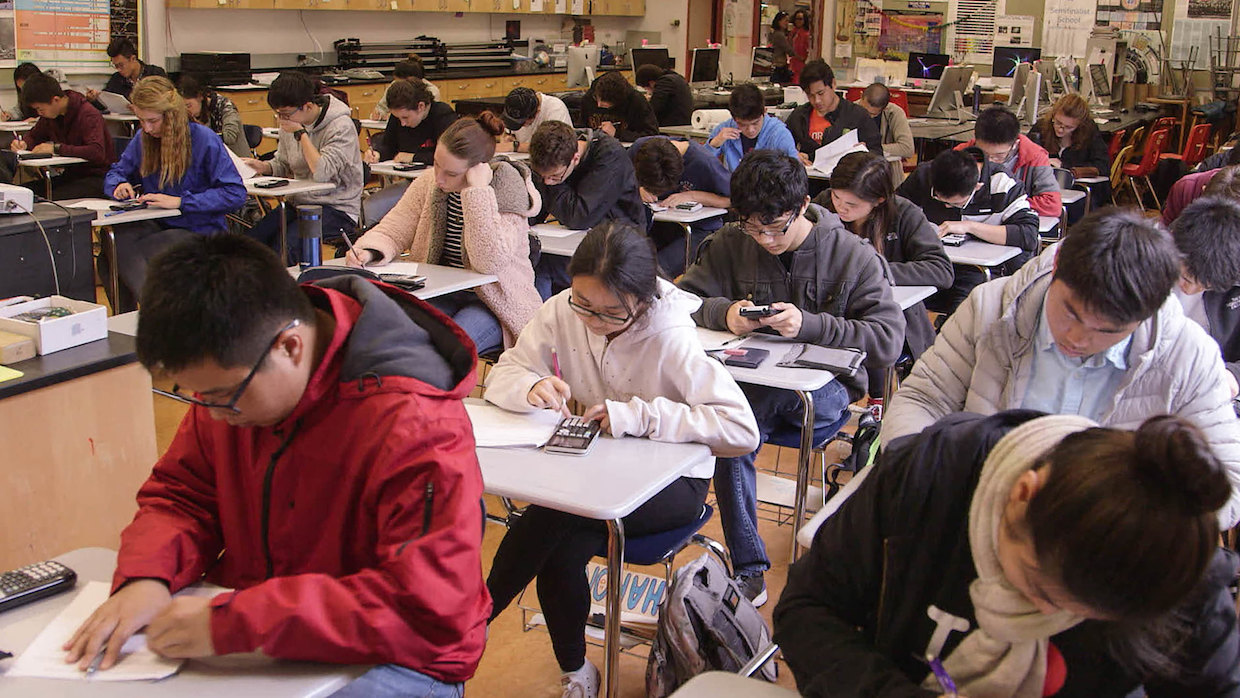

Try Harder! Lowell High School, whose student population is predominantly Asian American, is different from most US high schools portrayed on film. Director Debbie Lum came to the nationally ranked school to portray Lowell’s students, particularly so called “tiger cubs” in the heat of the college admissions process for her Sundance 2021 doc Try Harder!. Of course, not all of the Asian American students shown in the film have stereotypical “tiger moms,” and it’s refreshing to see an array of Asian American parents and students shown in communities where they feel comfortable, rather than shrinking in the minority. But the pressure on the whole student body to make it into an Ivy League school is upheld by peers in a competitive environment with a rigorous college preparatory focus.

There is also an admissions process for students to get into Lowell, which factors for their GPA and how well they score on the school’s admissions test. But, as reported recently, the school is now considering a randomized lottery system to address issues of exclusion that “perpetuate the opportunity gap.” Black students make up only 1.8% of Lowell’s current student body. The other 50.6% of Lowell students are Asian, 18.1% are white, and 11.5% are Latinx. The school is not impregnable to racist patterns that occur when a community has clear and slanted majority and minority groups.

To universities like Stanford, high achieving Asian American students are of one type: “machines” without vibrance and range. When Lowell students asks a visiting recruiter from Stanford why the school historically has not accepted their students, the recruiter answers them with a question, “Would you want all your students to look the same?” The Asian American students at Lowell are constantly reminded of this disadvantage, and know they aren’t getting things because they’re Asian. And whenever Rachael, a Black and white biracial Lowell student, is rewarded or acknowledged for the work she’s done, her peers often lash out and tell her she only gets things because she’s Black.

Lum has directed and worked on documentaries about Asian American subjects for year, such as Seeking Asian Female and early collaborations with Spencer Nakasako, a story consultant on this film whose son, Lou Nakasako, D.Pd and produced the film. Lum spoke with us about how and why she chose the five Lowell students she followed most in Try Harder! and how she narrowed her portrayal of the eclectic student body in ways that defy tradition and archaic diversity quotas.

Filmmaker: The rapid cutting in the opening sequence really captures that anxious pen-tapping rhythm of the period leading up to college entrance exams. How’d you come to this opening?

Debbie Lum: First question about that, love it—that was almost the last thing we did. [laughs] “Try harder!” That’s sort of the siren song for all documentary editors, I think. Lowell Highschool is such an alternate universe, and there’ve been so many high school films, also tons of documentaries, and a school like Lowell had never been filmed before in a doc. We had many [opening] scenes. We tried to start with a verite scene even. But I really wanted to capture the perspective of the students from the get go, knowing you were going to be seeing it through their lens, and not necessarily [that of] the teachers, the parents, the grown ups.

I worked with three amazing editors at different stages. The other thing about independent documentaries is that they take a long time and you run out of funding, so you have to go and [get] some more. [laughs] Amy Ferraris, who edited Seeking Asian Female, started out editing and was also a Lowell alum. Then we had to pause, raise more money and brought on Andrew Gersh, who edited Crip Camp. But the opening itself was edited by Victoria Chaulk who has edited a lot of great indie docs too.

Filmmaker: How did you get funding in between?

Lum: We started by getting a grant through California Humanities, which is an amazing organization if you’re making stories about California. Center for Asian American Media (CAAM) had funded all my films and shown my films in their festival, and they’re part of the minority consortium for public television, which is more of like a partnership. We got completion funding from ITVS, which is funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting—it’s basically public television. XTR came on as an executive producer, another amazing organization. In between all that we also had the support of individuals. We thought about doing a Kickstarter, we sent out letters to friends and family. I did not put it on a credit card, but it took a really long time.

Filmmaker: Lowell has a large student population. How did you come to five students being the scope of the film?

Lum: I started out as an editor. The documentaries I edited were single character documentaries, long form portraits. My last film was an intimate story about a marriage. So, making a multi character documentary was totally new to me. A typical number is usually three, maybe four; we had five students, plus a whole high school as a character. We didn’t know how it would unfold, so we followed more than just the five and had to make difficult choices in the editing room. Some of that too, is looking at diversity through a different lens. Three of our characters are Asian American, one of our characters is biracial—Black and white—and the other one is white. We definitely had people on the way that told us we should make it a story about an Asian kid, a Black kid and a white kid. I found that to be very frustrating: it’s a predominantly Asian American school, and there’s really no visibility on Asian American stories to begin with. To gut the story so that it was one of each seemed to be an outdated mentality, so we really stuck to our guns.

Filmmaker: Can you talk more about how you vetted those students?

Lum: We did a lot of research, a lot of talking to people before we started, and we also did preliminary interviews with students before we started filming them. In a way it was a giant casting call. But we were earnestly trying to understand the perspectives of the students there. We interviewed dozens and dozens of students. We got to know a lot of the senior class; it’s a big school.

We met Alvan probably our first day there and knew we wanted to make a film about him. He was recommended to us by the teachers too. [laughs] There were so many great kids at Lowell. There were other students too, that we filmed more of but who didn’t make it into the film.

Filmmaker: Lowell has “Lowell Gods,” the kids everyone knows will get into Stanford or Harvard, or a top 10 school, and succeed. Jonathan Chu is one of those “Lowell Gods,” or the “Lowell God,” and he’s constantly talked about by the kids and captured on camera at events. But although he’s on camera, he never talks to it. Why do you keep him on the outskirts of the film?

Lum: A lot of people are fascinated to know what happened to Jonathan Chu. The funny thing about Jonathan Chu was that he was always being talked about in the hallways and the classrooms. You’d walk into a classroom and the kids would be talking “Did you hear Jonathan Chu did this or that?” [laughs] We heard all about him before we met him. He was not only the president of their class, he was like a ruling dynasty. He was the president from freshman to junior year. When he became a senior, he moved over to becoming president of the entire student body, instead of just his senior class. Other kids would tell us “I’ve been wanting to run for president, but if Jonathan Chu’s running there’s no point.”

We just loved how he had this aura and lived-in mythology for these students. That was much more interesting than actually finding out. Like one of our characters said, his storyline is so predictable. We all knew that he was going to get in and there wouldn’t be that much struggle, and that doesn’t necessarily make for great filmmaking. [laughs]

Filmmaker: Watching the film, I kept thinking about Keva Rosenfield’s 1984 documentary All American High. He got access to everything, filming the highschool students drinking at “keggers” and parties—and I’m sure it wasn’t the only high school doc shot around that time that did so. Obviously, it would be hard to pull off something like that today. Young people are more aware of the camera. What is access like in high schools today?

Lum: Considering we were filming predominantly Asian American students, they were much more comfortable in front of a camera than I was expecting. I think that has a lot to do with technology being so pervasive, YouTube and TikTok. TikTok wasn’t around quite yet while we were filming, but it’s the same ethos. I’ve worked on films that focus on Asian American characters my whole career, like one you mentioned earlier, Kelly Loves Tony [part of Spencer Nakasako’s doc trilogy]. Sometimes we get shy in front of the camera, do you know what I mean? Technology has made people more comfortable. All those Asian American youtube influencers are influencing a whole generation of young people.At the same time, the college admissions frenzy is something that people are comfortable shining a spotlight on. We weren’t going out to film students at keggers, as you said. [laughs]

Filmmaker: You don’t extend far from the school or much into the exterior lives of the kids in the film. Why is that?

Lum: We wanted to look at the high school and stay in the classrooms always. I thought of it as like Charlie Brown and the Peanuts; the adult figures are basically just the sound wahwahwah. That’s what we really wanted to do in the beginning. But once we got to Lowell, we could see it had its own ecosystem. The film really looks at the parental pressure, but also there is the pressure from peers, the students themselves. The community of the school had a huge impact on the students, so that’s why we were staying there.

I started out making a film about Tiger Moms and looking at the college admissions journey through the perspective of a mom’s obsession with the future of their child. There’s a high school in Fremont, California called Mission San Jose where we spent a little bit of time. That school is 95% Asian American. It actually used to be a white working class farming community that over the years became primarily Chinese and Indian. We were talking to moms and looking at it from their perspective, but then realized it would be interesting to look at the so-called “tiger cubs.” We heard about this program at Lowell called the Lowell Science Research Program, where sophomores, 14 year old students, are doing graduate level medical research and presenting papers. The way they talked sounded ridiculously high achieving.

When we went there and met the students who were in that program, we could not understand anything they were talking about. [laughs] It was like, “I can’t understand anything you’re saying.” Way over my head. How did these kids become this way? And what did their parents do to make them that way?

Filmmaker: Race was never talked about at my high school, but the kids at Lowell are always talking about it and have much more of a grasp of it.

Lum: Race was at the forefront of their conversations because the college admission process asks students to identify themselves in racial categories, and they were being told by college counselors to think about themselves in those terms, so I think that’s part of the reasons why it’s like that. I grew up in the midwest, and I was one of the only Asian Americans. It was very, very different. Everyone was sort of…whatever you wanna call it, color blind. But when you’re different, you always think about that, I think.

Filmmaker: Rachael’s experience really resonated with me, and she particularly had a strong understanding of the inner workings of Lowell.

Lum: We knew Rachael was a minority within a minority school. I figured she was going through something different than what a lot of the other students were going through—not just different from the Asian American students, but also from Shea, the white Jewish kid, and others. But I think the reason why she was such an important character in our film is her relationship with her mom and her openness. She was always so emotionally present with us, and sort of typified the attitude of the students there who don’t know their own self worth. They are so pressured to compare themselves to the person who got the higher score. Like she said, it’s harder to have higher self esteem when you’re comparing yourself to others. As adults, we were very aware of how courageous she was, her ability to share everything she did with us. She also has a great sense of humor. We fell in love with all of the kids.

Filmmaker: Did the COVID-19 lockdown present any challenges in post production?

Lum: We definitely had to go through a period where we just shut down. I have three kids in elementary school, now one is in middle school. Once we went into lockdown and all three of them were at home, I became their school principal and had to do all the disciplining, which is apparently what school principals do. [laughs] It was impossible to get anything done on the film. But in some ways it just streamlined the natural process. When you get into post sometimes you’re working with an editor that’s not in the same time zone, or sometimes not in the same country. Our editor was in Portland and our composer was recording the music down in Los Angeles. I’m in San Francisco. So it was all Zoom calls and Dropbox, basically.