Back to selection

Back to selection

Focal Point

In-depth interviews with directors and cinematographers by Jim Hemphill

“The Second Movie I Operated On”: Camera Operator Lou Barlia on Love Story

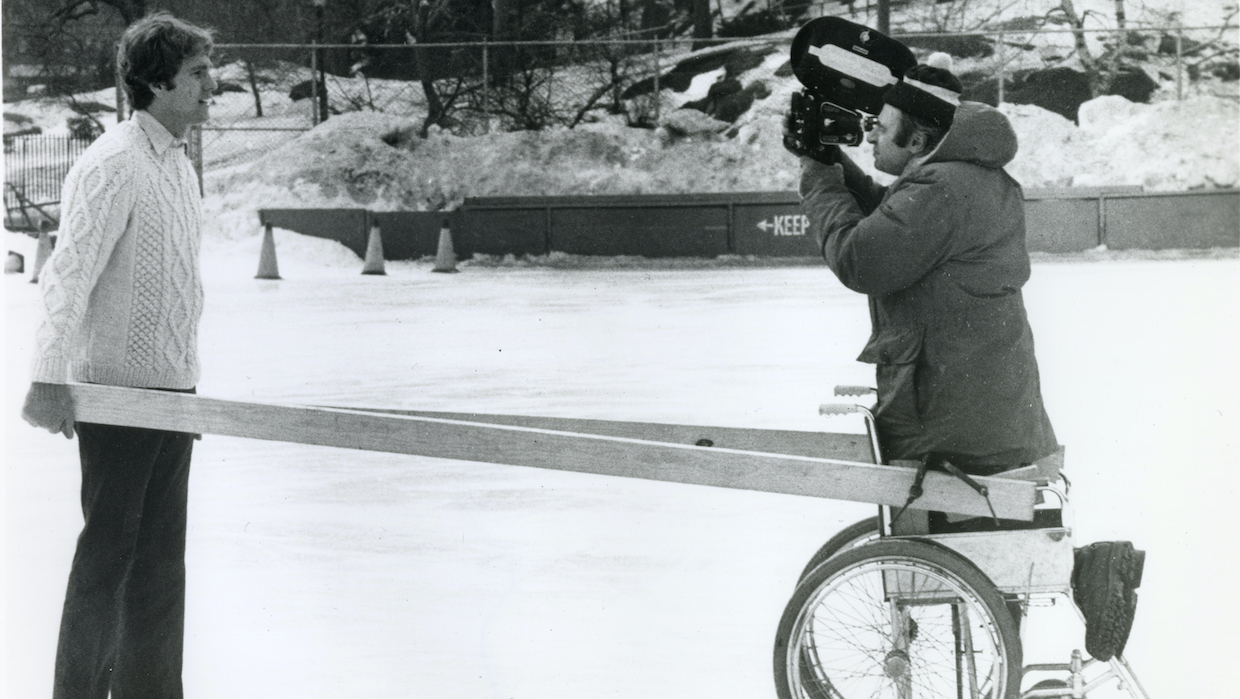

Ryan O'Neal and Lou Barlia on the set of Love Story

Ryan O'Neal and Lou Barlia on the set of Love Story When I revisited the classic tearjerker Love Story last month, I was struck by the intimate connection between the actors and the camera; at every given moment, Ryan O’Neal and Ali MacGraw’s doomed young lovers seemed perfectly showcased for maximum emotional impact, every gesture and expression captured from the proper distance and in perfect proportion from shot to shot—undoubtedly one of the reasons the film was the most popular of its year (1970), whether audiences were conscious of the delicacy of the framing or not. What’s all the more impressive about Love Story’s camerawork is how off the cuff some of it seems; a great deal of the movie is shot hand-held, as though the camera is just stumbling on to the lovers, yet the spontaneity is clearly by design, precisely attuned to the emotional effects director Arthur Hiller is after. This elegantly choreographed dance between camera and performers is the work of camera operator Lou Barlia, who was at the beginning of his feature operating career when he worked on Love Story. To look over his subsequent credits is to see a list of some of the most iconic American movies of the last 50 years: Serpico, Death Wish, Superman, The Big Chill, Fletch…along with multiple collaborations with John Cassavetes, Paul Mazursky and Burt Reynolds, among many others. On the occasion of Love Story’s new Blu-ray release—it’s been meticulously upgraded by Paramount from a new 4K restoration in a package with terrific supplemental materials—I spoke with Barlia by phone to hear about how he approached operating on what would become one of the most beloved cinematic romances of all time.

Filmmaker: Love Story was pretty early in your operating career, at least as far as features go. How did you get started in the business?

Lou Barlia: My background was in still photography, but when I entered the service during the Korean War I got in as a combat cameraman, shooting strictly black-and-white Tri-X or Plus-X. When I got out, I managed to get into the union that operated out of New York, at that time called Local 644. Initially I joined NABET for 25 bucks, and they were giving 644 a lot of competition, so the 644 decided to absorb NABET and I was part of that merger. They asked me, “How do you want to come into the local? Do you want to come in as a cameraman or as an assistant?” I thought it would be more fun coming in as an assistant, because then I could get to know all the cameras and stuff like that. This is 1954. I came in as an assistant and started working like crazy on commercials. Features were just starting to come into New York, but they weren’t really shooting the whole movies there—they would come in and shoot some backgrounds to get a New York look, and I would shoot plates and stuff like that.

I got married and had a couple of boys, and there came a point where my wife Betty said, “Lou, it’s time you moved up.” You had to put in an application to change your category, which was from assistant to DP; there was no operator category in New York at that time. I put in my application, and while I was working as an assistant on a commercial in Bermuda the union called from New York and said, “Lou, call Dick Kratina. He wants to use you on something.” Dick was a young cameraman himself who was about to do this movie called The Pursuit of Happiness for Robert Mulligan, a heavyweight director at the time. He asked me if I wanted to operate for him, and I said, “Are you kidding? You sure you want me to move up? I’m just changing my card right now.” He said, “Don’t worry about anything. You’ve been around a while. You know the cameras. How would you like to do it?” I said, “Okay, great.”

So I moved up, and I was crapping in my pants on the first day of shooting. The cameras we had were Mitchell BNCs, and there were no monitors at that time—when they asked how the shot was, the operator made the decision if it was good or not. The first shot on the first day happened to be probably the toughest shot on the whole movie, it involved some moves and a zoom. I did it and the director said, “Lou, how was it?” Everybody looked at me kind of cross-eyed, like “What kind of answer is he going to give?” I gave them the right answer, and we got through the first day. Then the second night, we’re all sitting in the screening room looking at the dailies that we shot the day before. I remember sitting there with my fingers crossed, and when I looked at Dick Kratina, he had his fingers crossed. We watched the dailies, and afterward everybody got up and gave me a hand and congratulated me on my first day of shooting. I felt like a million bucks. I was like, “I finally made it.”

Filmmaker: How soon after that was Love Story?

Barlia: That was the second movie I operated on. I got the call right after The Pursuit of Happiness. I should say that meanwhile, before all this stuff, I was actually DPing commercials in New York. So, getting these calls to operate was kind of new to me. But I got the call for Love Story, did Love Story. Then I got a call for another movie, and another movie, and another movie, and before you know it, I got pretty darn busy.

Filmmaker: The hand-held work in Love Story is extraordinary.

Barlia: There was no Steadicam at that time, so if you wanted to get those kinds of shots you had to do them handheld. I was really happy with some of the handheld scenes like Ali MacGraw and Ryan O’Neal rolling around in the snow, which we filmed when we went back to Boston for some reshoots. It was a skeleton crew, just myself, Dick Kratina, Arthur Hiller and an assistant. We got to Boston in April, and on the following day when we were set to shoot, they had a major, major snowstorm. The question was, should we just forget about it, or maybe go out and grab some shots? So we went out. I believe it was back at the Harvard Yard. Arthur gave me an Arriflex and got the actors to go out and play in the snow and throw a football around. The music that they used to go with that particular scene was kind of haunting, and it turned out to be a really, really cute moment in the movie. Then of course the following day, it was pouring torrential rain. So we shot some scenes in the rain.

Filmmaker: The location shooting at Harvard really makes the movie, and there’s one great camera move I wanted to ask you about. MacGraw and O’Neal are walking across campus talking about Oliver’s father, and you follow them in what looks like one unbroken take—but as you said, there’s no Steadicam and nowhere to hide dolly track because of the way the couple keeps changing direction. So how did you do that?

Barlia: In order to dolly with the actors without laying tracks, the company paved 300 feet of asphalt—that way we could put the dolly right on the path the actors are walking on and move with them. The problem is that it was winter, bitter cold, and the day we were going to shoot we found out the newly paved asphalt had cracked all along the way. We couldn’t do the shot with a normal dolly, so we used what they call a Western dolly, a platform with four balloon tires to absorb the shock of the bumpy asphalt. We tied a tripod with a Mitchell BNC down on chains onto this platform.

As you said, the shot involved changing directions, several 360s, and Arthur wanted to do it all in one—I think it took something like 300 feet of film. Arthur liked to do a lot of takes, so we were up to…I don’t remember exactly how many, but maybe something like take 15. I’m looking directly through the lens of this Mitchell, and it’s difficult because of all the swift moves on this tripod. Because of what it took physically, my eyepiece started to fog up. I kept saying to myself, “Oh God, please. No, not now, not now, not now.” And before you know it, it was just a whiteout. I could not see the actors. It was about halfway through the shot, this long dolly shot, and I had no choice. I had to cut the camera. So I cut, and Arthur said, “Lou, what happened? Why did you have to cut?” I said, “Arthur, get over here quickly and look through the camera.” He looked through the camera, and he said, “Okay, I can see why.” I thought at that point maybe they were going to use it in two pieces. But I refreshed myself by looking at the movie again last night and it was used as it was intentionally supposed to be used, as one long dolly shot.

Filmmaker: I feel like the camerawork is very responsive to the performances, which is one reason that movie ages so well. There’s a real intimacy between you and the actors, like you know exactly where to be at every given point to capture their most affecting moments.

Barlia: It’s funny, because looking back, I’m my own worst critic. There’s all that hand-held stuff of Ryan O’Neal playing hockey, and when he sits down, the shot is a little soft. When I saw that last night, I said, “Oh, crap.” But that’s the way it was in those days. I probably saw it, and mentioned it, but because of all the action that was going on they just let it go. The hand-held stuff is a little jerky, but maybe that worked well for some of the scenes. I’ll never forget when Boris Kaufman, a New York cameraman who was one of my idols—he won the Academy Award for On the Waterfront—came to the cast and crew screening. When the movie was over and we were on our way out of the screening room, Boris came over to me and said “Lou, I’m very, very proud of you. You did a wonderful job.” I felt so great going home that night. He was a great cameraman.

Filmmaker: I love all those movies he shot for Sidney Lumet. Who you ended up working with a few years after Love Story, right?

Barlia: Yeah, I worked on Serpico with Lumet. He was the type of director that really, really did his homework. I mean, he knew lenses. Before the movie started he would rehearse with his actors and a viewfinder so that when the actual shooting took place he knew exactly where the camera was going to go. He’d say, “Put the camera here, with a 50-millimeter lens,” and that’s where the camera stayed. We couldn’t plan on much overtime on the movie—we would finish at 3:00 or 4:00 in the afternoon because of the way Lumet worked—but it was a real pleasure.

Filmmaker: And then you also worked with John Cassavetes, who I’m guessing works quite differently from Lumet.

Barlia: I worked with him on a couple of things, Minnie and Moskowitz and Gloria, and I also worked on a movie called Tempest that John acted in directed by Paul Mazursky. I worked on a lot of movies with Paul Mazursky, he was a great, great director and a great human being. Always a pleasure, he took you in as one of his family.

Cassavetes was one of a kind. As an actor, he was very stable, but as a director he was eccentric, really nuts—and let me tell you, he didn’t give a crap about focus! He drove crews crazy. One day, they love him; the next day, they want to quit their job. But all told, he was a wonderful person to make movies with. Again, you felt like you were part of a family working with him. He was great guy.

Jim Hemphill is a filmmaker and film historian based in Los Angeles. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.