Back to selection

Back to selection

Six Favorites from the Just Concluded 2021 New Directors/New Films Festival

Rock Bottom Riser

Rock Bottom Riser After moving its 2020 edition to December and shifting to online-only viewing, New Directors/New Films returned to its usual springtime slot for its 50th iteration in 2021, combining virtual screenings with in-person ones at the Museum of Modern Art and Film at Lincoln Center. The fest celebrated its golden anniversary with a streamable selection of films that played at ND/NF in years past — early work by luminaries such as Chantal Akerman, Charles Burnett, Lee Chang-dong, Christopher Nolan, and Humberto Solás. However, this well-deserved victory lap was just a sidebar to the main program: 27 new feature films, along with two programs of shorts. I’ve chosen six favorites from this year’s slate to write about here.

Alice Diop’s documentary We is ostensibly structured around the RER B train line that traverses Paris and its surrounding suburbs from north to south. But the film’s true subject only gradually comes into view as the director leads us through several locations and neighborhoods along the train’s route. We meet a Malian immigrant who works as an auto mechanic and lives out of his van; Diop’s sister, a health care worker who goes from door to door checking on her elderly patients and administering their medications; a gathering of French Catholics observing the death of Louis XVI. Diop adds an auto-biographical element to the mix by incorporating home-video footage of her late parents, working-class immigrants from Senegal who paid into a fund that would send their bodies back to their homeland for burial after they died.

What begins as an accumulation of local scenes and individual histories expands to become a wide-angle view of contemporary France — a country where the old ways are uneasily making room at the table for new ones, where the resting-places of kings now share the screen with those of humbler humans. Diop makes her intentions explicit in a scene near the end of the movie, when she appears on camera to interview the author Pierre Bergounioux. Bergounioux relates that he turned to writing to exalt through literature the lives of the poor inhabitants of Corrèze, the region he hails from. Then both writer and filmmaker speak of the similarities between their self-appointed artistic tasks, “to provide a trace, to conserve the existence of something that would disappear,” “dragging from the darkness folk who had lived without ever seeing reflections of themselves in books and onscreen images.” The seeming warm-blanket coziness of We’s title belies the magnitude of the film’s ambition: to redefine, through the act of cinematic representation, what it means to be French.

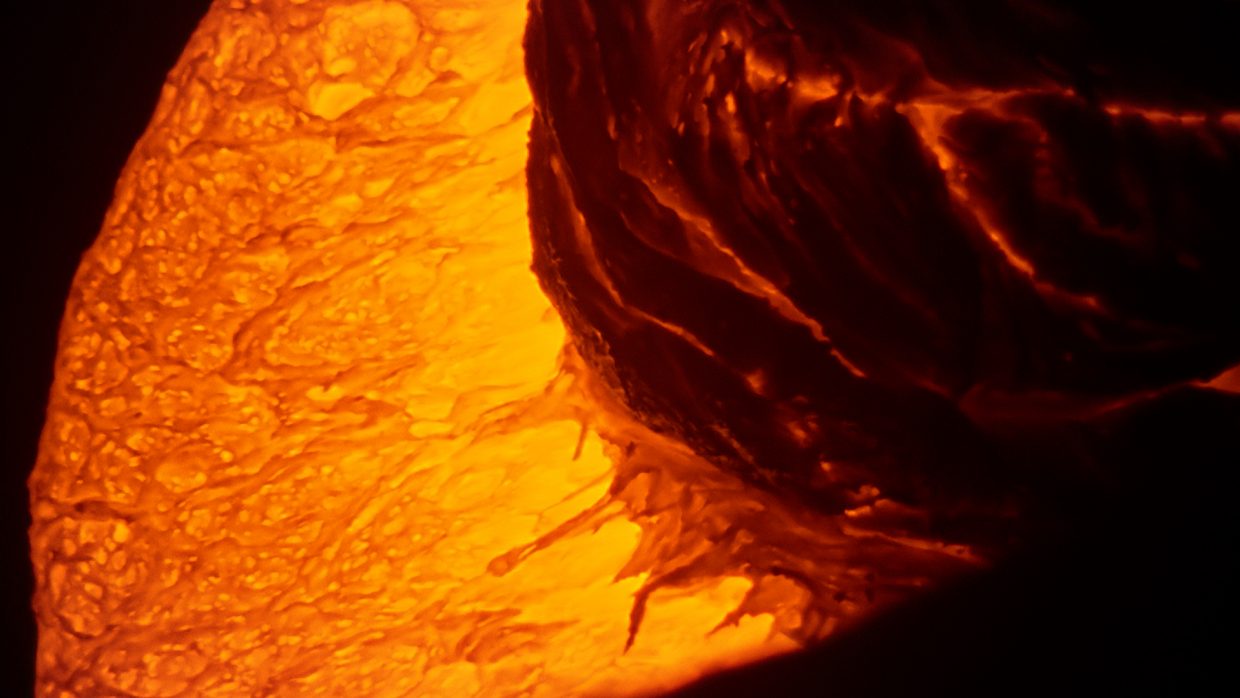

Another ND/NF documentary, Fern Silva’s Rock Bottom Riser, also takes an essayistic approach, but it’s a looser, baggier thing altogether. Silva’s topic is Hawaii, and how its native traditions and fierce natural beauty have been threatened by colonialism in the past and corporate rapaciousness and environmental degradation in the present. The film hopscotches from stunning drone shots of lava surging forth from volcanoes to lectures on astronomy, ethnography, and geography (some served up straight, some verging on parodies of academic discourse); from polemics against the planned construction of the world’s largest telescope on sacred land to gnarly slo-mo surfing footage.

If Diop neatly ties the fragments she collects to her main thesis, Silva is making connections that are more intuitive; the viewer has to do some mental work to fit the parts into a coherent whole. And cohere they mostly do, although there are times when the connections appear slippery at best: a montage of young men doing vape tricks hardly seems to bear any relation to the rest of the film, except that the vape shop where it takes place is called “Volcano.” But it’s a witty, delightful showstopper of a scene, one of the movie’s high points, and it would take a sterner critic than me to fault Silva for indulging his gift for crafting bravura cinematic passages, which is on ample display throughout Rock Bottom Riser.

Iva Radivojević’s Aleph takes its name and inspiration from Jorge Luis Borges’ short story about a man who discovers a portal that allows him to see everything that ever existed all at once, “the place where… all the places in the world are found, seen from every angle,” so that all places and times become one. No film could capture this. (No prose work could, either; Borges’ narrator despairs of being able to communicate his experience to the reader.) But Radivojević aims to suggest a similar feeling of infinitude by weaving together ten stories from ten different countries, each one flowing into the next, as if everyone in the movie, and by extension everyone on the planet, is a single protagonist in a never-ending narrative. Thus, two Bedouins in the Algerian desert talk about how you can never see the stars in New York. The film then transports us to New York, where a former movie star from the former Yugoslavia tells a sympathetic listener about the years he spent in prison, when he dreamed of escaping to a monastery in a distant land. At which point we’re whisked to a monastery in the Greek mountains…

According to Aleph’s press notes, the director travelled to each country in search of a subject/actor; once found, the subject would collaborate with her to devise a narrative framework for their section of the film. Each section takes its subject’s real life as a jumping-off point, but each is also a highly wrought work of fiction. As the movie’s geographic scope widens, so does its expressive palette. Radivojević’s virtuosity as a filmmaker is nothing short of breathtaking; she serves up a banquet of styles and modes of address, from austere slow-cinema long takes to Escher-like psychedelia to dreamy poetic reveries. Hardly a minute goes by without a striking image, a startling edit, or a right-on-the-money music cue. The ideas and motifs that thread through the stories create a feeling of unity out of wildly disparate materials, but like Rock Bottom Riser, Aleph lingers most strongly in the mind as a treasure chest of memorable moments and marvelous set pieces.

Winner of the top prize at Rotterdam this year, the Indian film Pebbles begins with a scowling man storming into a run-down country schoolhouse demanding to see his son. The energy is cranked up to a high level from the start, and the first-time writer/director P.S. Vinothraj keeps it there for the next 66 minutes (the end credits continue for another eight minutes, presumably to stretch the film out to a more commercially acceptable length). The man’s wife, the boy’s mother, has run away to escape her husband’s abuse. The husband, a mean, drunken brawler, takes his son on a bus ride to her ancestral village to find her; when they arrive, they learn that she has already headed home, to be with her son. Father and son then walk back on foot.

Pebbles’ slender plot and short running time don’t hint at its astonishing dramatic power and richness of detail. Most of the movie takes place under the wide-open skies and blistering sunlight of rural Tamil Nadu, but it has the claustrophobic intensity of a classic film noir. And along with it, noir’s unsentimental eye for social relations: poverty is a constant presence in the movie (in one extraordinary scene, a family burns dry grass to smoke rats out of their holes, then breaks the rats’ legs so they can’t run away, then skewers and roasts them), and it’s the women who bear most of poverty’s burdens. The film begins and ends with shots of women retrieving water to bring back to their families, reminders of who creates and sustains life. By contrast, the main character is a force of pure destructiveness, driven only by appetite and impulse.

The flat, dusty, drought-parched terrain of Pebbles is central to the experience of the film; the same could be said of the setting of Pablo Escoto Luna’s All the Light We Can See (not to be confused with Theo Anthony’s documentary All Light, Everywhere, ND/NF’s closing night film this year). Here, it’s the cloud-capped twin volcanoes Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl in central Mexico and the lush woods and valleys that surround them. If the place is specific, the time of the story is indeterminate: perhaps it’s the 1800s, or the early 1900s; at one point a character speaks of the “atomic wars,” at another we hear 1994 radio broadcasts from the Zapatistas. Escoto, a young director working with a miniscule budget, has crafted a visionary epic that aspires to the condition of folk tale, or myth — a myth informed by Mexico’s real history while taking place in a realm outside of it.

All the Light We Can See alternates between two stories, that of María, who flees from her arranged marriage to the sinister El Bandito and escapes into the forest with her lover, El Toro, and that of Rosario, who mourns the death of her great love, El General, killed by the military after his attempt to lead Mayan rebels in a coup failed. The film aims for an elemental power and grandeur, and largely succeeds; Escoto uses cinema to evoke a world that feels pre-cinematic, pre-modern even. That he achieves this with the most minimal of means is a tribute to his aesthetic resourcefulness, and a triumph of DIY filmmaking. In the daytime scenes, the blurry, not-quite-hi-res digital video images take on the texture of landscape paintings seen through frosted glass; at night, shadows swallow up most of the screen, with faces and bodies partially revealed in small pools of light in the vast darkness. This is a film that depends on spareness, stillness, and slowness; it demands the viewer’s close attention, and amply rewards it. Nothing I’ve seen in the last 14 months of watching movies at home has made me miss the big-screen experience more.

One thing I’m always hoping for from new directors and new films — which ND/NF has reliably supplied in the years I’ve attended — is experimentation with form. True originality is rare, but you want to see younger directors come up with their own approach to film language, rather than mimic the forms of the past. Films like Aleph, Rock Bottom Riser, and All the Light We Can See satisfied that hunger. What about a film like Eyimofe (This Is My Desire)? This first feature by the twins Arie and Chuko Esiri, who were born in Nigeria and raised and educated in England and the U.S., is standard-issue cinematic realism. The movie is divided into two parts. In each part, the protagonist — a male engineer in the first, a female hairdresser in the second — tries to leave Nigeria for better opportunities elsewhere. (The engineer’s story is titled “Spain,” the hairdresser’s “Italy,” after the countries to which they hope to emigrate.) Both find their way blocked: by bad luck, by bureaucratic inefficiency and government corruption, by the greed and duplicity of friends, family, and strangers.

From its pleasing 16mm grain to its smartly deployed plot twists to its conventionally well-rounded characters, everything about the way Eyimofe is told feels familiar. Yet the film is put together with such intelligence and skill, and is packed with so much fascinating social and cultural insight, that I was completely drawn in for its nearly two-hour running time. The camerawork is fluent and unobtrusive, the framing mostly medium and medium-wide to better display the characters in their environment — Lagos, the sixth largest city in the world, is shown here as humming with energy and color as well as danger and desperation. If the shape of the two stories points toward a kind of pessimistic determinism, a brief epilogue leaves the door open to the possibility of a brighter future. A movie like Eyimofe proves that classical storytelling traditions can still offer vital views of our present moment.