Back to selection

Back to selection

Jim Hemphill’s Home Video Recommendations: Lady Sings the Blues, Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart, The Bureau: The Complete Series

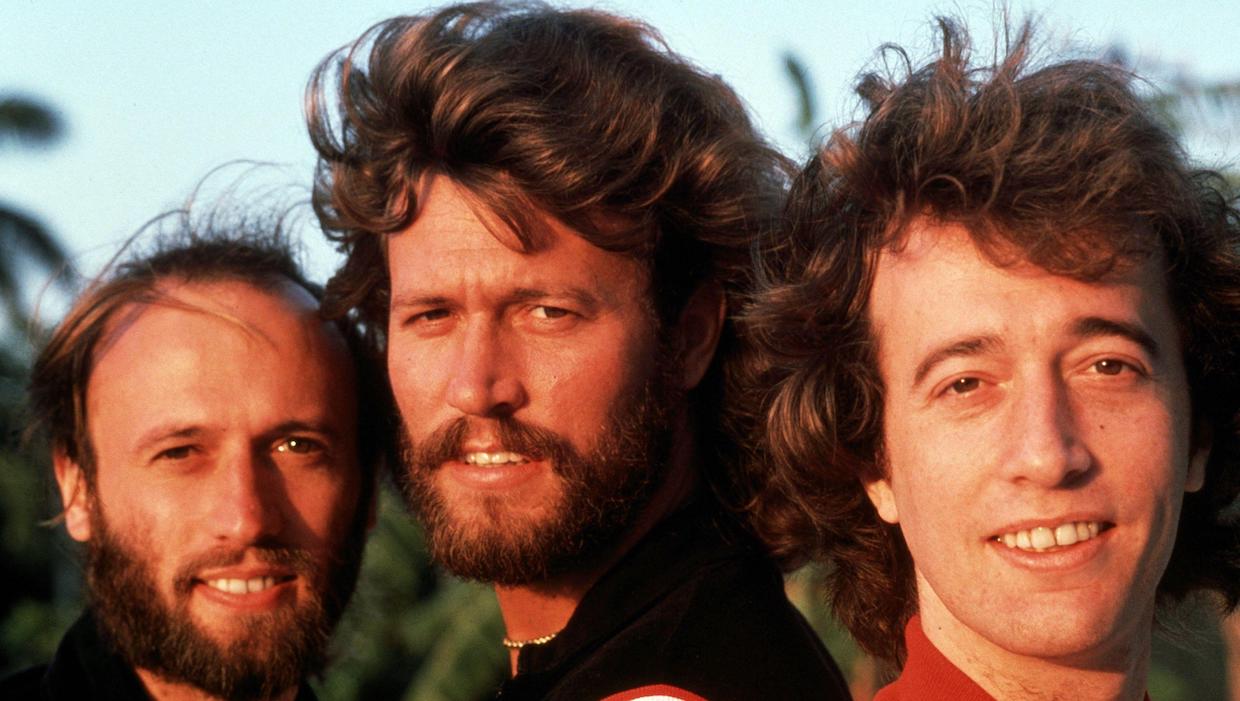

Barry, Robin and Maurice Gibb (courtesy of HBO)

Barry, Robin and Maurice Gibb (courtesy of HBO) When Motown Records impresario Berry Gordy made his debut as a filmmaker in 1972, the dominant mode in Black cinema was that of Blaxploitation flicks like Shaft and Superfly or gritty indies like Melvin Van Peebles’ politically and formally radical Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. Gordy saw a void to be filled—and an opportunity to showcase his label’s biggest star, Diana Ross—by producing a glossy, old-fashioned Hollywood melodrama with Black performers; the result, the Billie Holiday biopic Lady Sings the Blues, was a landmark musical that catapulted Ross to an Oscar nomination and instantly created a new standard for leading men in the form of Billy Dee Williams’s spectacularly charismatic performance. Director Sidney J. Furie, one of the American film industry’s great masters of widescreen composition, stages every scene for maximum dramatic force, showcasing Ross, Williams and costar Richard Pryor in iconic, star-making frames lit by the great John Alonzo just a couple years before he would hit a career high point with Chinatown. The result is a document of, and testament to, Billie Holiday as well as Diana Ross, captured here at a pivotal moment in her career just a couple years after leaving The Supremes. Yet as dazzling as Ross is, what’s remarkable about Lady Sings the Blues is the way her male costars anchor the piece; I’ve never felt that Pryor’s comedic films captured what made his stand-up special, but for some reason he really shines in dramas like Lady and Paul Schrader’s Blue Collar—he seems incapable of a false note in those pictures, while in stuff like Silver Streak and Stir Crazy he always comes across as uncomfortable in his own skin and uneasy on camera. Lady Sings the Blues contains one of Pryor’s best performances as the sidekick who deeply loves Billie, while Williams conveys both suave charm and aching vulnerability with exceptional skill. The movie has been reissued on Blu-ray from Paramount in a gorgeous transfer, accompanied by a making-of documentary filled with fun stories about the film’s creation.

Another terrific music movie, Frank Marshall’s Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart, is newly available on all major digital platforms this Tuesday (and continues to stream on demand on HBO and HBOMax, where it premiered last December). The documentary follows brothers Barry, Maurice and Robin Gibb from their childhoods in Australia to their early success as a British Invasion band in the 1960s and subsequent reinventions as a disco juggernaut in the 1970s (their Saturday Night Fever soundtrack was the most successful album of all time until Michael Jackson dethroned it with Thriller) and a songwriting powerhouse for other artists (Barbra Streisand, Kenny Rogers, Celine Dion, etc.) in the ’80s and ’90s. It’s a lot of material to cover, but Marshall, writer Mark Monroe and editors Derek Boonstra and Robert A. Martinez have structured it for supreme entertainment value and emotional impact; the pacing is flawless, moving quickly through the decades without rushing and delivering information in a manner that is clear to the newcomer without boring Bee Gees enthusiasts. It’s a master class in documentary filmmaking, lively and thoughtful with a strong point of view yet minimal editorializing; like a great Bee Gees song, it’s a masterpiece of meticulous construction and heartfelt inspiration that comes across as effortless. Marshall never strains for his results, yet somehow manages in 110 minutes to tell the moving story of a family (with lovely detours to include fourth Gibb brother Andy and his solo career) while also providing a crash course in the pop cultural movements of an entire era and poignantly examining the disorienting psychological effects of both success and failure as well as the bittersweet acceptance of finding happiness somewhere in between. It’s a beautiful, rousing piece of work that makes one extremely excited for Marshall’s upcoming series on Paul McCartney; his passion for this kind of filmmaking and for the musicians he showcases is as infectious as his storytelling skill is impressive.

My final recommendation this week is Kino Lorber’s new 15-DVD boxed set The Bureau: The Complete Series, which collects all five seasons of creator Eric Rochant’s brilliant spy drama. After The Bureau premiered in 2015, Le Figaro called it the best French television show ever made; I don’t have a wide-ranging enough knowledge of French TV to corroborate this assertion, but I can say that Rochant’s incredibly complex and powerful thriller is as great a series as I’ve seen from any country. A twisty ensemble tale with an intensely affecting Mathieu Kassovitz at its center, The Bureau recalls the best of John le Carré and Graham Greene in its ability to rigorously mine the espionage genre for insights into the devastating effects intelligence work can have on both those who perform it and those who get in its way; as one of the characters points out, human life is just a form of currency in this world, and it’s as worthless to the forces of politics and history as it is invaluable to the creators behind the camera who invest The Bureau’s characters with such excruciating longings and weaknesses. The series boasts a formidable directing team (helmers include Pascale Ferran, Jacques Audiard and Kassovitz himself), and its precise, elegant style provides the perfect visual corollary for its characters’ cool surfaces, surfaces that conceal violently roiling internal tensions. In a way it’s like a prestige version of Miami Vice; like that series, The Bureau yields endlessly fascinating explorations of what it means when an undercover agent plays a role for so long that he or she begins to prefer that role to real life—and what the consequences of that are and how one agent’s carelessness or solipsism can reverberate around the world. The show is as suspenseful as it is intellectually stimulating, and as politically sophisticated as it is accessible in its universal truths; it’s immediately involving and addicting, making Kino’s boxed set a perfect way to swallow it all down in one satisfying gulp.

Jim Hemphill is a filmmaker and film historian based in Los Angeles. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.