Back to selection

Back to selection

“This Film was Just 11 Days”: DP Maz Makhani on The Guilty

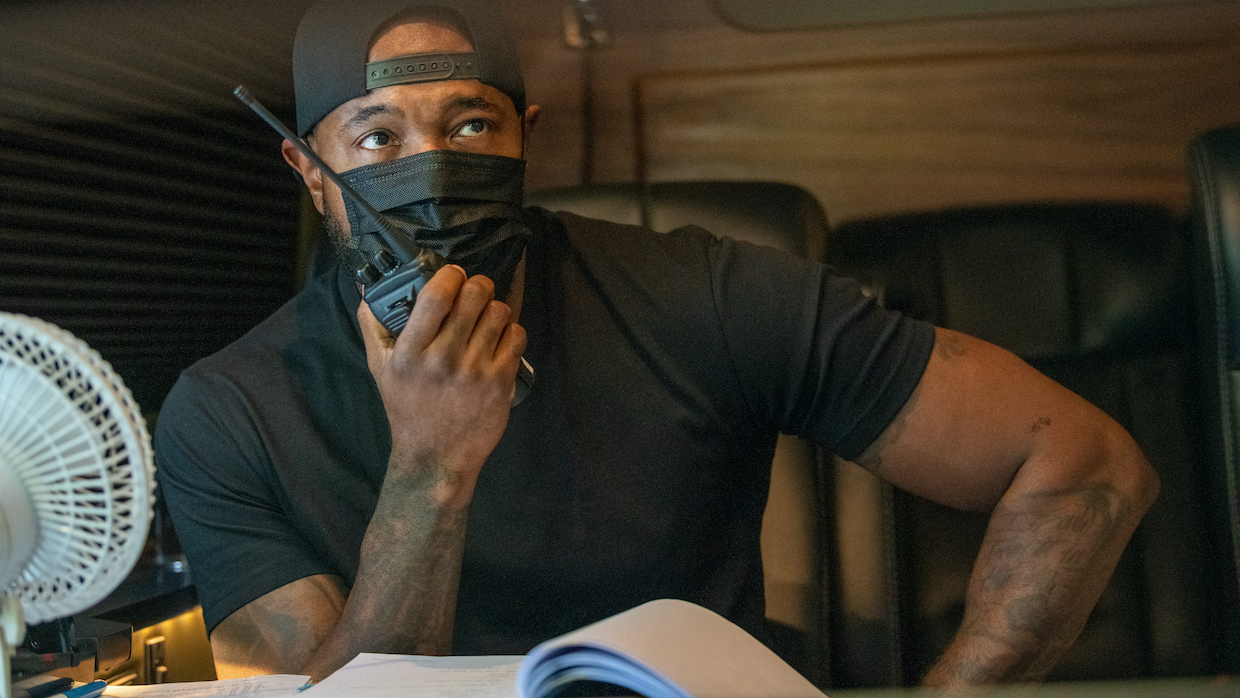

Antoine Fuqua on the set of The Guilty (Photograph by Glen Wilson, courtesy of Netflix)

Antoine Fuqua on the set of The Guilty (Photograph by Glen Wilson, courtesy of Netflix) When cinematographer Maz Makhani met director Antoine Fuqua on a Lil Wayne/Bruno Mars video a decade ago, the rapport was instant.

“It was really clear to both of us that we had a very similar aesthetic,” said Makhani. “We both liked the same compositions, the same type of lighting. Antoine juxtaposes the real and raw and gritty with style and beauty, and that’s also my aesthetic.”

That simpatico relationship went from a luxury to a necessity on the new film The Guilty, when COVID forced the pair to shoot the Netflix thriller without ever being on set together. Days before the start of principal photography, a close contact of Fuqua’s tested positive for COVID. Though the director’s test came back negative, protocol required him to quarantine. Due to the 11-day schedule, that isolation effectively rendered him unable to direct in person.

Rather than shut down production days before cameras were set to roll, Fuqua set up shop a block from the studio in a monitor-filled van and helmed the movie remotely. His only in-person interaction with star Jake Gyllenhaal came when the actor would climb atop a ladder on the edge of the studio wall and Fuqua would slide open his van door for a socially distanced chat.

Based on the 2018 Danish film, The Guilty unfolds almost entirely in a Los Angles 911 call center, where a demoted cop (Gyllenhaal) frantically tracks a kidnapped woman from his desk post. With the movie now streaming on Netflix, Makhani spoked to Filmmaker about its singular production challenges.

Filmmaker: You’ve done several low-budget features throughout the course of your career, but your most well-known work has been in music videos and commercials. I’d say that The Guilty is the most high-profile movie you’ve shot thus far. What’s it like to make that leap at this point in a very established career?

Makhani: It hasn’t hit me yet. What’s interesting is that this film was just 11 days. The amount of work that I put into some of the lower budget films that I’ve done has been so significant, where we’re shooting for weeks and weeks and maybe even months, whereas this happened so quickly. It came together quickly and ended quickly. It’s a little surreal that we were able to make a full-length film in such a short period of time, but I’m super happy and grateful that Antoine and I finally got to do a feature together where I was primary DP.

Filmmaker: How important was having an established relationship with Antoine considering the way you had to shoot this film?

Makhani: That made it much easier, of course. We did our walkthrough a few days before we were going to start principal photography [before Antoine was in quarantine]. So Jake, Antoine and I were actually on set and Jake was sitting at his character’s desk. Antoine and I spent some time walking around the space and saying, “Okay, this is a great spot. This is a great spot.” There’s never been a time when I think Antoine suggested to move the camera to a certain spot that I didn’t agree with. We really do see eye to eye on how things should be composed and blocked.

Filmmaker: A lot of directors watch takes from video village, so maybe the process wasn’t as different once you were rolling. But when you’re blocking scenes and setting up shots, now Antoine can’t see the actors in the space on the day or walk around with the director’s finder to think about angles.

Makhani: Well, ultimately, Jake is sitting for most of the film. That certainly really helped these circumstances of Antoine not being on set. What I tried to do as best I could was just find the right frame so Antoine didn’t have to change it. For the most part, everything we framed up worked. We had three cameras and would do 20 minute takes at a time, which was how big the cards were for the camera. Then we’d find another three angles and go again. Jake knew the script really well, so we could get through a lot of dialogue in two takes and have six camera angles of it.

Filmmaker: You’re right, Jake’s character is sitting at his desk for most of the film and that does simplify things. But that also presents its own challenge, because now you’ve got to come up with 90 minutes of interesting coverage for a largely stationary lead character talking on a phone headset.

Makhani: I don’t think that Antoine and I ever specifically had a conversation about it, but we turned out to be in mutual agreement on a plan to start wider on Jake in the beginning and, as the tension grows and we’re getting deeper into his psyche, toget closer and closer to him. I referenced some older Tony Scott movies from 15 or 20 years ago and also Michael Mann films, and what I discovered was back then a lot of these types of psychological thrillers were shot on long lenses. Now, because of the advent of lenses that don’t distort as much when they are used on the wider end, you can actually take the camera closer to peoples’ faces and stay on wider lenses and be closer to the actor. There were a few shots we did on a 600mm zoom, but, for the most part, for the heavy dialogue sequences toward the end of the film, I wanted to get as close to Jake as possible. It was very challenging for my focus pullers and for Jake, too, to be able to act freely when there’s a camera inches away from his face.

Filmmaker: What did you choose for your camera and lenses?

Makhani: We had three Alexa LF’s and I used the Hawk 65 Anamorphic primes. We discussed shooting this on film. Of course, being a cinematographer, film is the dream. But with film, sometimes you have to overlight, because it’s not as sensitive as modern digital cameras, and I wanted to create an environment where the ambiance of the space did a lot of the work in terms of lighting. So, by shooting digital I could shoot in lower light situations and allow the space to do most of the lighting, then augment it with the desk lamp and the computer monitors. We didn’t want the image to be too sharp either, so then you offset that by using glass that’s not too sharp, which is one of the reasons I shot anamorphic so that I could take the edge off. I think the lenses we chose really were perfect for this film. However, I didn’t get a true lens test. We just didn’t have that time. I did a really quick camera test and said, “Okay, they don’t flare too much. They have a really great quality, they are high contrast and they look beautiful. Let’s go with these.” We literally started shooting the lenses without a proper camera test.

Filmmaker: You said you used a 600mm. Was that from that Hawk set?

Makhani: Hawk does make a 600, but it’s a spherical zoom. But the glass matched absolutely perfectly with the anamorphics we used. Once you color it, you can’t tell. They cut beautifully.

Filmmaker: You’re shooting some longer focal lengths on large format and anamorphics, all things that decrease depth of field. What kind of stop did you shoot at?

Makhani: I shoot everything wide open.

Filmmaker: Everything?

Makhani: Well, if you’re using older vintage lenses, some of the old anamorphics don’t like to be wide open and you’ve got to stop down a little bit to a 2.8 or a 4 or sometimes even deeper but with modern glass that doesn’t matter. You can shoot wide open and it really makes no difference. There’s no falloff on the edges. So, you’re able to really get that super-compressed image without having to sacrifice the stop.

Filmmaker: You talked about trying to take some of the sharpness away from the camera. Did you use any on-camera filtration?

Makhani: No, I didn’t. The only thing that I used a lot of on Jake’s close-ups were diopters, because even though these were pretty close focus lenses considering they were anamorphic, you still had to use diopters to get even tighter. So, I used diopters a lot towards the end of the film as we got closer to his face. I also had a 100mm macro I used a lot for the ultra-tight close-ups, things like his eyes and his mouth and the headset. That lens was a really great tool in the arsenal.

Filmmaker: For prep did you look at any photos or visit call centers to see how those sorts of spaces are lit?

Makhani: Antoine and Peter Wenham, the production designer, actually did a lot of research. They wanted to keep our set as authentic as possible. They wanted it to be cool and modern and obviously beautiful to photograph in, but kept it very true to how a communication center would be.

Filmmaker: The film has two principal locations. There’s the main call center room where Jake starts the film alongside co-workers. But eventually his shift ends, and he takes up a new post in an auxiliary desk in a nearby empty room by himself. Break down the lighting for that first room for me.

Makhani: I really liked the idea of super warm light coming into the room in the beginning of the film when the sun is about to set and keeping it very clean and simple. For that opening section at sunset, my gaffer Blue Thompson and I had a few 20Ks that we warmed up with CTO coming in at a very low angle. Then after we go to the night interior look, I wanted to separate Jake from the space. Peter Wenham hung these [fluorescent-like] practicals above the set shooting downward, but it wasn’t quite enough in terms of juxtaposing different color temperatures. I really wanted the ambiance to be one thing and the lights on the workers’ tables to be another. So, we put strips of light ribbon on top of the practical fixtures shooting up toward the ceiling. It was a light-colored ceiling so I could [bounce that light ribbon] and create an ambiance. I made that ambiance much colder, with the color temperature more like 5000K, to juxtapose the warmer light from his desk. There’s a lot of different color temperatures in that room, versus just going with clean white light and calling it a day.

Filmmaker: How much work did the computer screens do in actually lighting Jake?

Makhani: You would be surprised how quickly those monitors, even at 20 or 30 percent [brightness], can overlight someone’s face when you’re shooting at 1280 ASA wide open on a fast lens. Particularly when it’s three monitors in a U-shape, if you’re not careful you can very easily lose shadow and shape. That light can get really flat, really quick. So, anything that was shooting toward Jake from the monitors’ perspective, I generally just turned the monitors off and used some small lights to actually light him for some shape. The question wasn’t really, “How are we going to light him?” It was more, “How are we not going to light him?,” because there were just so many opportunities to overlight his face in these environments.

Filmmaker: I did an interview recently with Matt Wise for Werewolves Within and he said his philosophy for lighting quickly and efficiently is something he learned from working with you—“Faces take five minutes to light. Backgrounds take five hours.” With The Guilty, you’re basically dealing with a couple of sets that are pre-rigged for the run of the show. So, your backgrounds are pretty much lit and now you’re mainly dealing with lighting those faces.

Makhani: The close-ups were relatively simple. I had a four-foot Astera unit that we were able to make red, at a three-quarter higher angle to emulate the reality of the light coming from a toppier source. I did accent Jake’s eyes, because I wanted to make sure you saw a glint in his eyes at all times. So, I had something on the table for him always, which was set closer to the color temp of what the monitors were doing. As that red light [atop each operator’s desk to signify an active call] got brighter and brighter in that second room, I found myself dimming the room darker and darker.

When he goes into that small room he closes all the blinds behind him. When you close those black blinds in a room that’s dark and all you’re seeing is someone’s face, it can get boring pretty quick, so I gave myself a little bit of creative latitude. The camera was a little lower than his eye-level sort of looking up, so I thought, “You know what? I don’t think anybody’s going to kick up a fuss if I open up these blinds just a little bit.” And when I did, it was magic. I remember as soon as I opened them up, I was waiting for Antoine to say, “Hell no, that wouldn’t happen in reality.” But instead, he said, “Looks good. Let’s do it.”

Filmmaker: What are the adjustments you have to make in terms of lighting style when you’re going from a glossy, high-end music video into a movie like this?

Makhani: I did have to think differently in terms of storytelling and realizing that sometimes less is more. Coming from music videos, I was a big fan of big, bright backlights—on this film, I wanted to have the discipline of not doing that. But when there’s an opportunity for it to happen organically by accident, I’m all for it. When Jake’s in the smaller room, the overhead lights that were in the hallway just behind that room gave him a really soft, beautiful edge that separated him from the black blinds behind him. By opening up those blinds a little bit we got a little backlight coming from this cool, overhead source. So, you still have to make it beautiful and interesting like in a music video, while also remembering that every light source should be motivated from something that could be real.

Matt Mulcahey works as a DIT in the Midwest. He also writes about film on his blog Deep Fried Movies.