Back to selection

Back to selection

“That Particular Phrase, ‘Arthouse,’ Has Hung Over My Head Like a Cloud of Contagion”: Wendell B. Harris Jr. on Chameleon Street

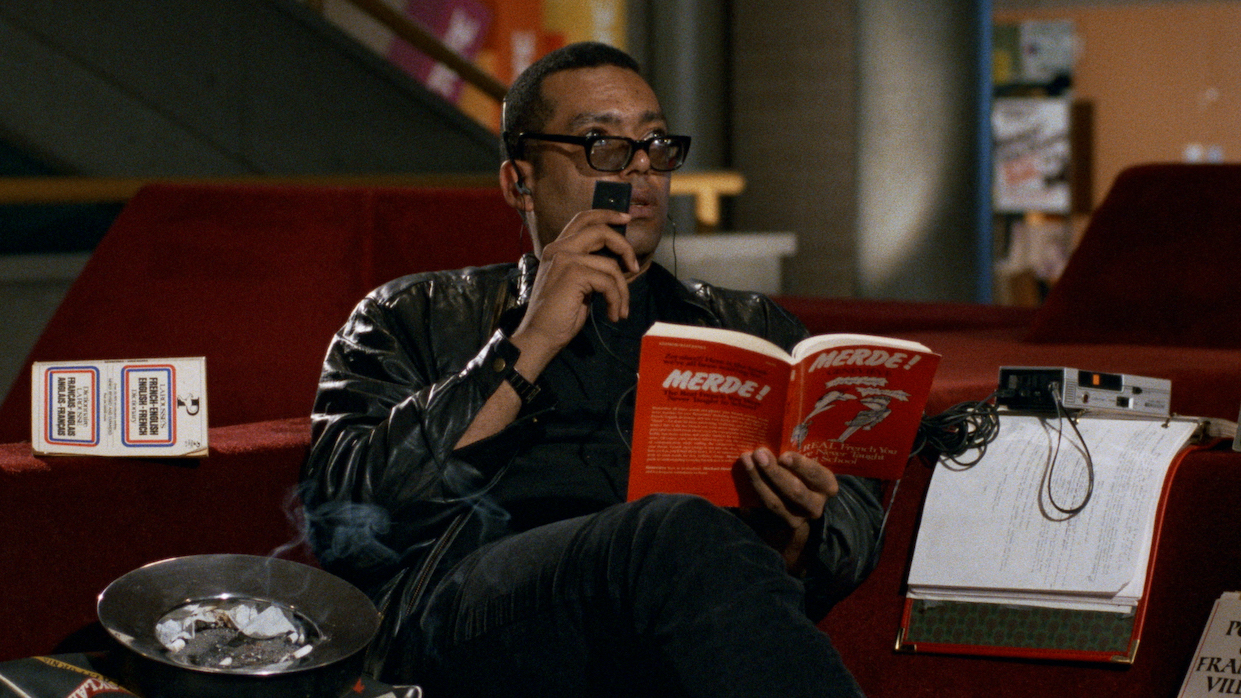

Wendell B. Harris Jr. in Chameleon Street (courtesy of Arbelos Films)

Wendell B. Harris Jr. in Chameleon Street (courtesy of Arbelos Films) William Douglas Street Jr. needed more money and less of a dead-end job. Working for his dad’s alarm installation company, he’d hit a wall. The only lucrative alternative was to deal drugs, but he refused to get wrapped up in that—instead, he became a conman and created his own opportunities after perceiving how arbitrary the barriers to higher-paying jobs and luxuries of high society are. Through his schemes, Street got to live the life of a Time sports journalist, a Chicago surgeon, a Martiniquan exchange student at Yale and many other personas—if only temporarily.

Wendell B. Harris Jr.’s Chameleon Street dramatizes the resentment Street felt toward the system and the people he gamed. Harris plays the real-life conman as all-knowing and viciously sarcastic, even towards people closest to him. Only Gabrielle (Angela Leslie), his wife and various lovers know the truth of his schemes, but Street keeps a mask on for them too. Harris lets the audience in on the film’s schemes and jokes—until, in a pivotal scene, the joke is suddenly on the audience, and the running punchline no longer feels as good.

It’s impossible not to feel the anger of this ruthless satire and redirect it towards the studio executives that have suppressed the distribution of Chameleon Street and Harris’s career. After the film won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in 1990, the debut director expected the floodgates of Hollywood to burst open, and the struggle to calm. But the gates had been bolted shut, and his struggle had just begun. Warner Brothers paid Harris for the rights to remake the film but never remade or distributed it. Chameleon Street didn’t fit into the categories or agendas that studio heads maintained for films by Black filmmakers, and Harris’ imagination would prove too expansive for gatekeepers in the years to come. But the film has survived and returned, newly restored in 4K—doomed to be deemed “timely” as if the film’s critique of the racist American empire is only present and fleeting, not futuristic or inherent to a society built on stolen land.

After the restoration screened in the revivals section of the 2021 New York Film Festival, I talked with Harris about his freeze-frames, approach to depicting Doug Street’s cons and re-distributing the restored film today.

Filmmaker: When’s the last time you saw Chameleon Street with an audience?

Wendell B. Harris Jr.: A couple of years ago at least. I was not able to attend last month in Manhattan. Have you seen the film with an audience?

Filmmaker: I went to two of the screenings at NYFF. It can be a quiet crowd, but I was happy that the audience got loud for both.

Harris.: Really?

Filmmaker: Yes! Lots of laughs.

Harris: Well, I have one question for you before we start. Setting aside Chameleon Street, what are your three favorite films?

Filmmaker: That’s hard. Maybe Teza (2008), Charisma (1999) and Manila By Night (1980). Can you think of three off the top of your head?

Harris: Well, now you’re jacking me up. [laughs] I just gave my top ten Criterion films. Amazingly enough, Criterion doesn’t hold the license on all the films in the world, so they didn’t have some of my favorites. When it comes to my top three, it may sound like an evasion, but it’s true—my top three changes almost daily. Today I would say Citizen Kane (1941), Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945). That’s just for today. Ask me tomorrow, and it will probably be three different ones. Although one of them, I’m sure, will be Kane.

Filmmaker: I hope Criterion gave you a copy of the new 4K Citizen Kane while you were there.

Harris: I only heard about it a couple months ago, and I’ve been trying to figure out who I’m going to tell that I want it for Christmas. Do you have a copy?

Filmmaker: I don’t. But I want to talk about Chameleon Street. There’s this running bit, which starts in the opening shot, where white characters use language against Doug Street, using words they expect him not to understand and then asking him if he knows what they mean. But then Street learns a myriad of gatekeeping career languages, develops his own twist on language and uses both to con his way into elitist spaces.

Harris: I would say that Doug, like many people, puts a lot of energy into weaponizing language. It’s funny, because on the first poster for Chameleon Street—and the latest poster that Arbelos Films just put out today, in fact—is the quote “I think, therefore I scam.” When the real Doug Street saw that, he contacted me and said he was offended they were using that line for the poster. I had to remind Doug that I got that line from him, and that nobody but Doug Street had put words into his mouth. So, Doug is extremely aware of language and uses it primarily to achieve the goals of whatever character he’s impersonating. I get the impression that people who talk to me about the film think that “Wendell made up this stuff; Wendell put that in; Wendell is the one who originated this and that.” Listen, I interviewed Doug Street intensely for three years and 98%, if not 99%, of what he does and says in Chameleon Street comes from him.

Filmmaker: Doug Street, the person, and the character, hates women. I read about how he resented his wife and his mistresses because he saw them as obstacles to his lies. They demanded more honesty from him, and that made him angry. I think some audiences will confuse Doug’s misogyny for yours as the filmmaker.

Harris: That kind of gets to the crux of Doug and his entire phenomenon. You know, the only negative reactions to Chameleon Street I ever really got were from people who actually knew the real Doug Street. Every once in a while I’ll get a Facebook message or email from somebody who actually interacted with Doug. They are always completely angered and appalled that a movie was made about him. This is not just indicative of Doug Street, but of every conman who has walked the face of the earth: The people who are closest—family members, teachers, girlfriends, wives, ex-wives—always end up feeling as if they’d been abused and ravaged by the relationship. I find it very interesting that part of the price Doug has paid in living this life for over forty years now is that he ends up alienating the people he’s dealing with. I don’t know if you’re aware or not, but Doug has never stopped. Chameleon Street essentially stops around 1985, but Doug has continued his exploits up until several months ago. He was incarcerated in 2014 or 2015 for impersonating a West Point general.

Filmmaker: Have you talked with him recently?

Harris: The last time we actually talked was—gee, 1995 when my company sent him his payment for the distribution of Chameleon Street on VHS.

Filmmaker: Did the fact that the audience has to believe Doug’s the smartest man in the room at all times affect how you cast the film?

Harris: I think I understand your question, which nobody has ever asked me before. I don’t think so, although inadvertently that may have played a part. When you write a scene, people it with characters, then cast actors directed to play what has been written and rehearsed—it’s like that line William Wyler told Charlton Heston. When Heston came to Wyler about shooting the chariot sequence in Ben-Hur, Heston pulled Wyler aside and said he wasn’t sure if he was gonna make it. Wyler turned to him and said, “Look, Chuck, just get into the chariot and ride. I’ll take care of the rest.” The movie is made almost in spite of the actors. I definitely want to say that I never cast any actor thinking: “OK, is he or she going to make Street look like the smartest person in the room?” It was more like, is this person going to play the part? That’s the top criteria. You don’t have to worry about anything except fulfilling that script.

Filmmaker: Most of this film draws from Doug’s experience, but doesn’t settle on “realism,” and is instead often quite expressive and stylized to Doug’s point of view. What were your thoughts about how realistically you wanted to portray this true story?

Harris: Before I answer your question, let me ask you a question, because you were there recently. What was the audience’s reaction to the hysterectomy scene?

Filmmaker: In both screenings a lot of people winced or looked away. You definitely feel the reality of that scene. [Street actually carried out 36 hysterectomies at a Chicago Hospital without getting past high school, let alone medical school.]

Harris: When you put a film together, you’ve got to pay a lot of attention to the tone. Although Chameleon Street has a very kaleidoscopic style, it is also extremely rooted in reality. Establishing a tone that feeds an audience’s sense of reality is something we very much worked for. In 1987, when we started filming, I kept telling the crew and the actors, “Make it like it’s real! Make it like 60 Minutes!” I kept saying that, because in 1987 there was no internet or social platforms. The extent of media reality that I kept using as a touchstone was “Make it like 60 Minutes!” That was because I did not want to inflate the action, overdo reactions or have overblown emotions. All of that would have worked against those three years that I talked with Doug Street about his reality. I don’t think that audience would have had a visceral reaction to the hysterectomy scene unless they had bought into the reality of Doug Street’s tone.

Filmmaker: Speaking of tone, there is an underlying anger and darkness to the whole film, but it really culminates in the scene where Street plays with his daughter with a knife, a mask and fake blood. The film becomes something much darker from that point on.

Harris: I’ll tell you something about that scene that I’ve never told anyone before, but is very, very true. I’ve always been interested in the reaction to the knife scene, because it’s the one and only time in the film when the audience gets to feel what it’s like to be conned by Doug Street. In the rest of the film, the audience is there with Doug and sees through everything that he does. But the only time the audience gets conned is in the knife scene, and that is why it’s there. I’m always kind of amazed by the reactions to that scene. You know, one time, for a screening of Chameleon Street in Detroit in 2014—for like six months we set up, worked on, planned and advertised this event at a museum in Detroit. And two days before the screening, I get a call from the woman in charge asking me if I thought it would be appropriate if they cut the knife scene from the screening. I was absolutely flabbergasted and floored. As I said, we had been preparing for this for six months, and two days before the screening they wanted to cut the knife scene. They were concerned that it would be too traumatic for the audience, and there were going to be some young teenagers as well, and they didn’t want to abuse the teenagers’ sensibilities. I said, no, I don’t think we should do that. That’s the only time that’s happened, and I only share that with you to say that particular scene seems to be a flashpoint.

Filmmaker: In the first screening I saw, there was a white guy behind me who kept saying “This is so weird” throughout the film. When the film got to the knife scene, he said it again, this time louder and angrier, stood up and left the screening.

Harris: Do you remember at what exact point he walked out?

Filmmaker: I think he had started walking out when the film revealed it was fake.

Harris: How old was the guy?

Filmmaker: Probably in his 20s.

Harris: And who did he say, “This is so weird” to?

Filmmaker: Just to himself, but loud enough for the people around him to hear.

Harris: [laughs] Oh, wow. And, as far as you know, he never came back?

Filmmaker: He never did, but I think it’s only a testament to the power of the scene. The rest of the audience was on board.

Harris: Oh no, it’s fine. I’m absolutely fascinated. I’ll tell you, I’ve seen some very interesting reactions to Chameleon Street. I’ll never forget, one time in Italy, I saw this middle-aged Italian laugh so violently that he actually fell out of his chair. I’ve only seen that in movies or on TV sitcoms or whatever. But to actually see that in real life—that has become a cherished memory of mine.

Filmmaker: Do you know what scene caused him to laugh that hard?

Harris: Yes, the French party scene.

Filmmaker: There’s a lovely moment in that party scene where you freeze the frame as the camera passes over Amina Tatiana’s face, and you hear Street say this is the last time he’ll see her face. You use this freeze frame technique a few times throughout the film. Can you talk about that particular example of it and its usage throughout the film?

Harris: That’s funny you would comment about that, because I very much love that scene. First of all, I do admit that, in high school, when I was at the Interlochen Arts Academy, where I first saw Jules & Jim, I was absolutely bowled over by Truffaut’s freeze-framing in that film. That made a big impression. However, fast forward 15 years while we’re making Chameleon Street. At a certain point there’s an interface between money and the choices you make. Every obstacle on Chameleon Street cost a certain amount of money. Every optical [any effect produced through optical printing, i.e. transitions, titles, blow ups, superimpositions, etc.] in Chameleon Street cost a certain amount of money from the house in Manhattan who handled ours. The guy who did our opticals had done them for Star Wars, and after he got done working on Chameleon Street, he said, “You have more opticals in Chameleon Street than George Lucas had in Star Wars.” I said, “I’m aware, because every one of them cost a huge amount of money.” But that particular sequence you’re asking about was definitely informed by Dan Noga’s camerawork, because that particular shot was so overwhelmingly effective that it virtually ordered me to make that montage happen. It’s a coda to Street’s relationship with Amina Tatiana, and it’s also the end of a sequence, the end of their relationship, which is, after all, an adulterous relationship. It all comes to an end in that one masquerade ball. That is one sequence that grew out of one shot. As soon as I saw that one shot, it dictated to me how it had to be followed by the same freeze-frame, closer up.

Filmmaker: What is it like for you to be revisiting the nasty distribution side of the industry with Chameleon Street again today?

Harris: Hey, now you’ve asked me about the dirty, conflicted, mire of distribution. It’s the one aspect of an independent filmmaker’s life that is essentially out of his hands. At the moment, Arbelos Films is handling the 4K restoration of Chameleon Street, and I am certainly impressed with the job they’re doing. But I can definitely tell you that the 30 years I spent prior to the 4K restoration had been absolute hell. You break your back to get the budget, you break the back of everybody who worked on the film’s hopes and dreams to actually get it made, and then, when you get it made, the next step for it is to be seen by as many people as possible. I can honestly say that 99% of Chameleon Street is exactly the way I want it to be. I can also say 99% of its distribution has not been the way I wanted it to be, at all—even 100%, I guess, if you set aside Arbelos at the moment. Distribution has always been the main fight, and brother I can tell you it’s a losing battle, because the independent filmmaker is not in charge, has no leverage and you’re essentially at the mercy of people under hands, under corporations, under conglomerates and other temporal powers.

Filmmaker: Where are you with your long-in-the-making documentary Arbiter Roswell?

Harris: It is very true that for 15 years I was using the title Arbiter Roswell in making and shooting the film, but the title had actually changed, in 2002, to Yeshua vs Frankenstein in 3D. Arbiter Roswell, although that is still the name of a section of the documentary, is no longer the title, because it’s misleading. I did not want to use a title that led people to think, “Let’s go see Arbiter Roswell, it’s like X-Files: All About Aliens.” That is not what the film is about, although it does definitely deal with the Roswell incident—it is not science fiction about aliens from outer space. What the film is about, is the absolute—absolute!—power of media to manage the lives and behavior of the masses. From 1500 to today, that is what the film focuses on—from Michelangelo to Michael Jackson, the power of media to program people. And that is how the Roswell Incident fits into the film. It is a PR event managed and produced by the Pentagon. And racism, which has afflicted America for 400 years, is also a behavior construct, a programmable behavior that can be abused, fed and maintained by media. When you go around looking at the Black image in film for 100 years, it’s an absolute atrocity. It is very much an accomplishment of a media that has been in place since the renaissance.

Filmmaker: In a past interview you defined “arthouse” as, simply, an un-marketed film. How would you define the term today?

Harris: [laughs] Aaron, my friend, you have asked the question that goes straight to my heart. That particular issue, that particular phrase, “arthouse”, has hung over my head like a cloud of contagion for 30 years. My comment about it has become even more simplified and to the point. Now, when I hear the word “arthouse” my mind immediately translates it to no money. Arthouse, is synonymous, for me, with no money. No profit, no distribution. I’ll tell you something that has stuck with me for some reason: have you ever heard of the movie Weekend At Bernie’s?

Filmmaker: Yes.

Harris: Weekend At Bernie’s came out around the same time Chameleon Street came out, which is why I guess it sticks in my mind. Today, I could walk around downtown Flint, where Chameleon Street was mostly filmed, and ask people, have you ever heard of Chameleon Street? And ten out of ten will say, “Never heard of it!” And that is not just in Flint. But wherever I go, I can go to people everywhere, and ask, “Have you ever heard of Weekend At Bernie’s?” And everybody has heard of Weekend At Bernie’s, if not seen it. My only point is that my company and I have been pushing Chameleon Street, along with film critics and film festivals, for the last thirty years, and the film has hardly made any dent whatsoever. Weekend At Bernie’s is known by everyone, Chameleon Street is known by no one.

Filmmaker: I think Chameleon Street probably leaves a mark on anyone who watches it. Weekend At Bernie’s may have been seen by everyone, but affected no one.

Harris: [laughs] I get what you mean. I only mention it because of your prior question about distribution. It is in the hands of the people who determine what the public sees. They have determined that Weekend At Bernie’s is going to be seen by everyone, that Tyler Perry is going to be seen by everyone, and that Chameleon Street is going to be seen by no one. And why is that? What is the thread of Chameleon Street? You very aptly said there are some people like yourself who have seen and appreciated the film, and I thank God for those people, because they have kept the film alive. But, as you know, I want Chameleon Street to be seen by as many people as have seen Weekend At Bernie’s. Can you arrange for that to happen?