Back to selection

Back to selection

“There Are So Many Parallels Between What Went On Then and Trying To Pass Biden’s Spending and Energy Bills Today”: Chris Hegedus on the Restoration of The Energy War, Part Two: Filibuster at DOC NYC

The Energy War, Part Two: Filibuster

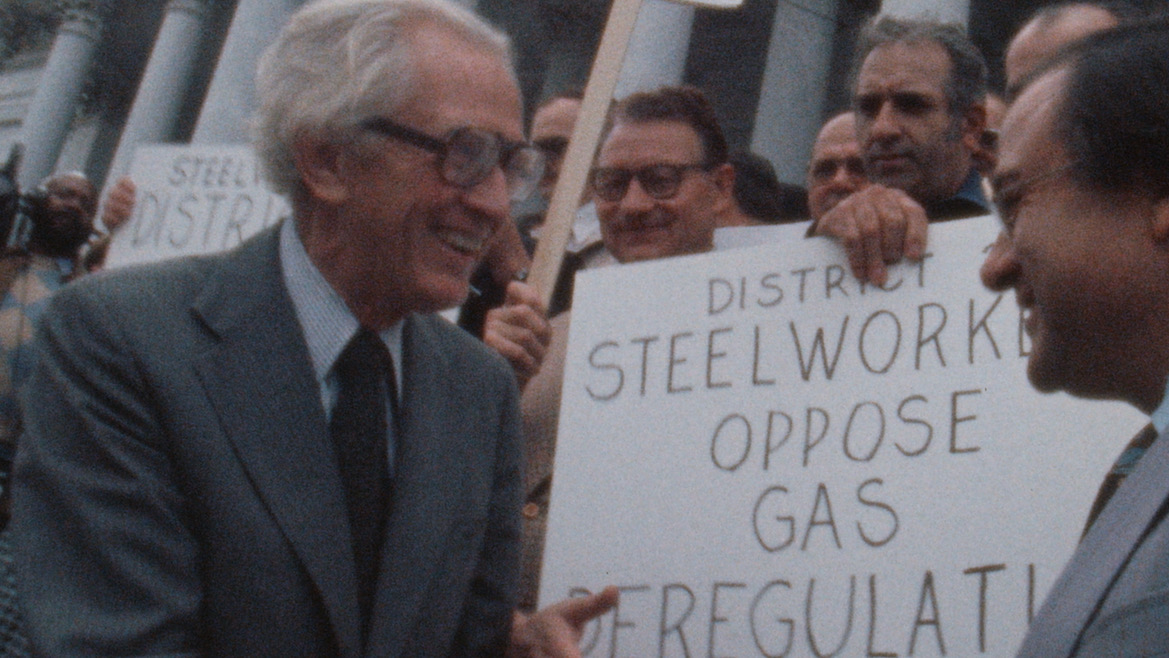

The Energy War, Part Two: Filibuster Originally released in 1978 as a three-part, five-hour series, The Energy War follows the passage of a key piece of President Jimmy Carter’s energy bill. Directed by D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, and Pat Powell, the series provided an unprecedented look at the inner workings of government. One segment, Part 2: Filibuster, focuses on Part D of Statute 1469, which would end government regulation of natural gas prices. It passed by a vote of 52–48, thanks largely to votes from representatives of energy-producing states like Louisiana. Two Senators, Howard Metzenbaum and James Abourezk, announce a filibuster to overturn the results. Over the following days, a counter filibuster begins.

The series was shot over a two-year period, in Washington, DC, but also in Texas, California, and wherever else the story took the filmmakers. The three directors worked with cinematographers including Cathy Olian, Joel deMott, Jeff Kreines, Ross McElwee, Michel Negroponte, and longtime associate Nick Doob.

Financed in part by a grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the series appeared on PBS. The Energy War was the basis of a course at Harvard, and later toured 32 countries under the auspices of the United States Information Agency. Pennebaker and Hegedus would go on to make The War Room, among several other documentaries.

The recently restored The Energy War Part 2: Filibuster will be screening at DOC NYC on November 13 as part of its “Luminaries” program. Barry Direnfeld and Thomas Susman, Senate aides at the time, will appear with Hegedus at a post screening Q&A.

Hegedus spoke with Filmmaker on Zoom.

Filmmaker: Can you talk about how this project began?

Chris Hegedus: Penny [D.A. Pennebaker] had been on the NEA panel and heard from someone there that the Corporation for Public Broadcasting had grant money for a film about politics and Congress. We had just had a huge energy crisis, long gas lines and everything else, so we thought we’d look into that. A Washington journalist told us that Carter’s energy legislation was going to be one of the fiercest battles ever in Congress. Then he said that the real fight was going to be over deregulating price controls on natural gas.

We were like rolling our eyes because it sounded so not sexy, lines of cars and tax legislation. But it was an issue that six presidents had battled for 30 years. We understood we would be walking into a sort of ground war. We made the pitch, got the grant, and started the film without any idea that this legislation would go on so long and feature a double filibuster.

It was a real fight. None of our team really knew much about congressional politics, so we were finding the story as it went along. We tried to hang on for nearly two years, making this film on a small grant which practically killed us.

Filmmaker: The story’s unfolding while you’re filming it, with so many people involved and more joining seemingly every day.

Hegedus: It was incredibly complex. For years we used to joke that if we had some kind of nightmare trying to solve editing problems, we would say we’re having “deregulation” dreams. It was hard to figure out how to tell this story in the dramatic way it really was.

Part of the excitement about the project was that nobody really knew what was going to happen, even if they were in the middle of the game. It wasn’t just “Washington behind closed doors,” but behind every closed door, there was another closed door.

Filmmaker: You shot this on 16mm?

Hegedus: Yes, I think 400 ASA. Penny and I had very handmade equipment. He would update the same cameras he shot with those early Drew Associates films in the 1960s.

Filmmaker: How much footage did you end up with?

Hegedus: In those days we didn’t talk about hundreds of feet and kind of spraying photography all over the place like we do now. The camera shot a ten-minute roll, and when it ran out the sound person would keep rolling and try to cover what was happening. It was a difficult process to tell a story that made sense when you had those shooting restrictions. It was also very expensive. Because our budget was so small, we started processing our film at a TV lab in New York. They kind of did it under the table, we’d give them the film in a brown paper bag and get the work print back in another bag. Overall we shot maybe 200 ten-minute rolls.

Filmmaker: How did you decide what people and events to cover?

Hegedus: We tried to stay on certain paths. Some people followed the filibuster, others the swing vote. Penny and I filmed a lot with the administration, that side of it.

Nick Doob, whom we worked with on a lot of films, was on our team. Ricky Leacock couldn’t come, but he sent two of his students from MIT: Ross McElwee and Michel Negroponte. We also had Joel deMott and Jeff Kreines, and our third director and partner Pat Powell, who had worked with Pennebaker and Leacock during the Drew Associates days. We worked mostly with two-person crews. It was a ragtag group, but interesting. Ross and Michel and Joel and Jeff, they hadn’t really made any films. They were in the process of developing their groundbreaking, personal diary type of films.

Filmmaker: What’s astonishing about the film is the access you had. You’re in the Senate Reception Room, in cars with Senators and their aides, even at home having dinner with Henry “Scoop” Jackson.

Hegedus: Jackson was great for us. He kind of let us into his life a little bit. He had just run for president but lost the nomination to Carter. He was like a kinder, gentler version of Russell Long, one of the lions of the Senate. People really respected Jackson, and he knew how to handle things. We tried to find the characters as the story went along. In Part One there are a lot more lobbyists, and they’re wonderful characters too.

Filmmaker: But you’re not just finding characters, you’re getting them to open up on camera in ways politicians wouldn’t think of doing today.

Hegedus: It was a pretty novel thing to do to follow people around in Congress. TV cameras were not allowed on the floor, but they also weren’t allowed to roam around the Senate Reception Room. When the TV news people realized that we were in there, they would get us thrown out. But I think in general, in terms of documentaries, most people didn’t understand what we were doing. They hadn’t seen any cinema verité documentaries. People were more concerned about the microphone than the camera in some ways. They figured if there wasn’t any sound, they couldn’t get in trouble. And in those days we didn’t have radio mikes, we had three-foot-long directional mikes. So we really stood out taking sound.

I don’t know, we just tried to weasel our way in, and we were able to do that in enough circumstances to film. Take James Schlesinger, who would become Carter’s Secretary of Energy. He called us “snoops” in the beginning. He would take great pleasure running to the elevator, with us following him, and have the doors shut right in front of us. It made him very happy. We followed him to Canada, to California, different places. I think what finally wore him down was that he saw we were really serious. We were staying in no matter what. Finally he gave us some really interesting access. It got to the point where he kind of snuck us into the Senate cloak room to record sound off the floor, because cameras weren’t allowed in there.

If people think you’re really serious and listening to them, that it’s about them and not us, they slowly start to let you into their lives. It’s a long process and in a lot of ways it’s the same process today in terms of getting access.

Filmmaker: But that doesn’t explain the intimacy you have with your subjects, the sense of familiarity with them.

Hegedus: We filmed in a very casual style. We were just two-people crews, we didn’t have any lights, we didn’t have any radio mikes. We weren’t trying to overwhelm them. It was much, much easier to kind of disappear.

Filmmaker: It’s depressing to see how little politics has changed over the past forty years.

Hegedus: There are so many parallels between what went on then and trying to pass Biden’s spending and energy bills today. Back then it was moderate and progressive Democrats going against each other, ripping parts out of the bill. Just like today

In Part Three there’s a scene in the House at night, Schlesinger is sitting in a room off the floor trying to recruit congressional votes. In comes Al Gore, this dashing young first-term Congressman, who turns Schlesinger down because all the solar credits and alternative energy parts had been taken out of the bill. You see Schlesinger’s face just fall as Gore marches out of the room. It very much reminds me of what’s going on now, these things are still getting yanked out of bills.

Filmmaker: Can you talk about the restoration process?

Hegedus: My goal is to preserve our archive, with almost 70 years of films. We’ve had partners with certain films. The Criterion Channel has helped with the ones with celebrities, like Dont Look Back with Bob Dylan, Company with Steve Sondheim, Monterey Pop. Our other films are important parts of history, but they are harder to see. Luckily we got some grants to do this second episode. Jamie Wolf’s Foothill Productions has helped fund a lot of documentaries. She and Edith Van Slyck were our executive producers.

We’re still in the process of trying to preserve the rest of the series as well as more of our archive. It’s expensive. When you go from 16 millimeter film to digital, you’re make everything sharper, but you’re also enlarging the grain. Then you’re trying to soften the grain without softening too much of the picture. It’s a very delicate balance.

We did color correction and some sound work on the film. Back then Penny had built a mixing studio with three tracks in our office. It was kind of like playing a musical instrument. But once you started you couldn’t stop, you couldn’t back up, you had to go to the end of the film. It was bizarre.

We also used a software program to reduce scratches. Because everybody with cameras had a scratch at one point, that was the nature of the system. So some of the scratches were taken out through this very elaborate process. It makes me laugh, because I just watched another film where they put scratches and dirt in to make it look more “authentic.”