Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

Headroom, Banding and General F-Stops: DP Haris Zambarloukos on Shooting Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast

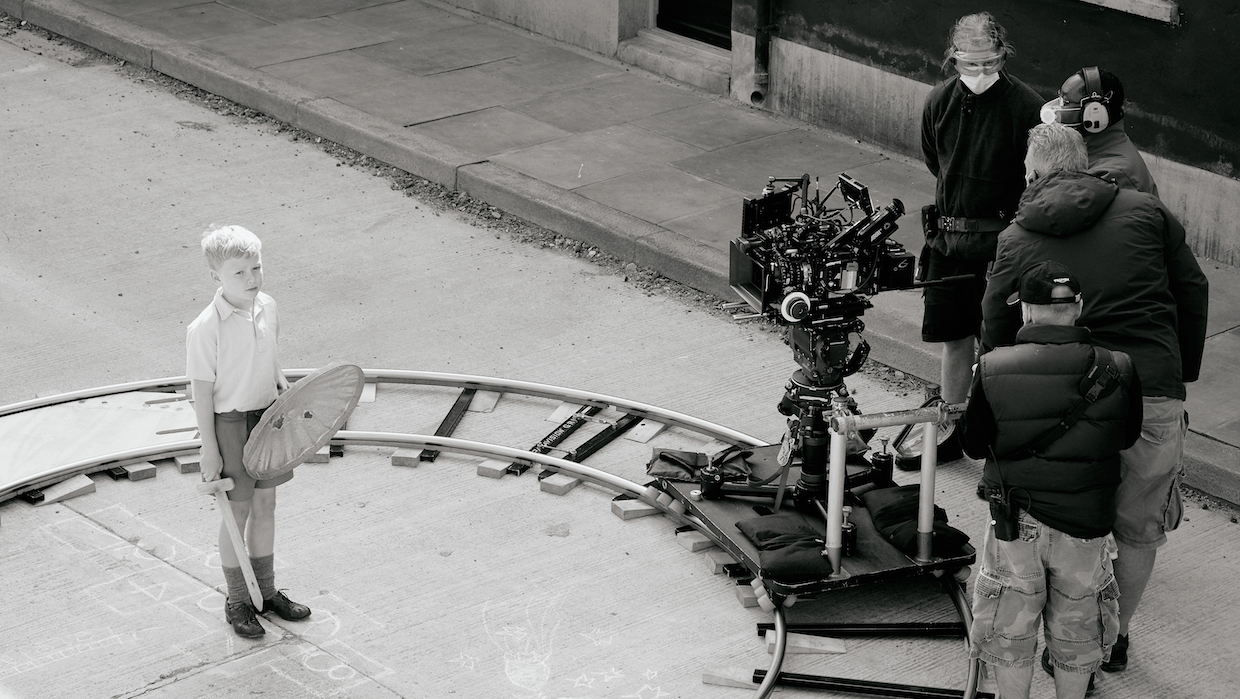

Jude Hill on the set of Belfast(Photo by Rob Youngson/ courtesy of Focus Features)

Jude Hill on the set of Belfast(Photo by Rob Youngson/ courtesy of Focus Features) Adorned with a wooden sword and a garbage can lid shield, nine-year-old Buddy (Jude Hill) begins Belfast fighting imaginary dragons, cloaked in the bliss of summer. That idyllic youthful revelry is ruptured by an explosion. That blast—and what follows—are based on the childhood remembrances of writer-director Kenneth Branagh, whose family was forced to grapple with the prospect of leaving its tightly-knit neighborhood after sectarian violence erupted in Northern Ireland in the summer of 1969. It’s a dilemma cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos understood well. Born on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus, Zambarloukos and his family departed following a 1972 military coup and subsequent invasion by the Turkish army.

“I had a similar history as Ken to some extent,” said Zambarloukos. “My father was an engineer and worked in construction and after the invasion he moved us to Dubai for work.”

Zambarloukos and Branagh also share a long professional history. Beginning with 2007’s Sleuth, they’ve made eight films together, ranging from Thor to a pair of Agatha Christie whodunits. All those previous projects were shot on film and with a 2.39 aspect ratio. With Belfast, the collaborators went digital, switched to 1.85 and lensed in black-and-white. Zambarloukos spoke to Filmmaker about that creative shift, why a medium format sensor feels just right to him and the lasting lessons from an internship with legendary cinematographer Conrad Hall.

Filmmaker: In Belfast, movies—both in the cinema and on television—shape how Buddy views the events around him. When you were that age, what films had an impact on you?

Zambarloukos: When we arrived in Dubai in 1974, there really was no television. I think they only showed the Quran five times a day for prayer. So, my parents bought a Super 8 projector. There was a little shop that sold condensed films, which were 20 minute versions of movies. I grew up with silent films like Chaplin and things like Herbie movies or The King and I—but 20 minute versions. Television began to appear in Dubai probably around 1976/1977, and by that time I was basically into Sylvester Stallone and Rocky. (laughs) But for me it really started with that Super 8 projector. I still have it, and the reels, to this day.

Filmmaker: Buddy watches American westerns—High Noon and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance—and Star Trek on television. Did those sorts of things play on TV where you grew up?

Zambarloukos: When we got back to Cyprus I was 11 and I remember Saturday TV was really important to me. It was The Pink Panther, Mork & Mindy and Happy Days. I loved the David Attenborough nature programs as well. We’d also get some free television in Cyprus from places like Czechoslovakia and these really interesting animations would pop up. It was easier to see films in the cinema in Cyprus than in Dubai, so moviegoing in a cinema didn’t really start for me until about age 11 and then it was things like Back to the Future.

Filmmaker: I was reading an interview you did with Panavision around the time Thor came out and there’s a great story about when you were working at Panavision Shepperton after finishing film school. You would help with camera preps and delivering gear to the stages. One of the sets you delivered to was Branagh’s Frankenstein adaptation in the 1990s.

Zambarloukos: I was very fortunate to be a technical trainee at Panavision at that time. They were very gracious with it, because I could go off and shoot projects, then come back and work. I really learned a lot about gear. But the best thing about it was certainly delivering equipment [to the stages]. Usually around 10 o’clock I’d check to see if there was a delivery and that was when the other technicians were taking a morning break, so I’d get half an hour to watch [whatever film was being shot on that stage]. The most impressive set I remember was on H Stage [for Frankenstein]. There was a tank with a ship in it and all these water and storm effects. I was used to having, like, a chair and a table. That was about as big as my sets were at the time. To walk onto something so huge was really incredible for someone so young.

Filmmaker: You also studied at the American Film Institute and interned for Conrad Hall on A Civil Action (1998). Are there things you learned from that shoot—either in terms of technique or just how to treat people and run a crew—that still inform the way you work?

Zambarloukos: Completely. Connie was a true poet and artist, and he had a really chivalrous, gentle way about him. He approached things completely and utterly from a story point of view and certainly made me aware that you have to look out for the little details. For example, on that movie he lit glasses of water or a water tank that was in the room in a certain way so that you’d always remember that the movie was about the differences between clean and dirty water. There were always these tiny visual clues he would dot around his frames.

One day we were shooting John Travolta’s office and it had all these windows to the side of him. I was always trying to figure out, “What would I do in this situation?” and, of course, I got everything wrong when I saw what Connie did. I assumed at that time that you would light that with window light—“Oh, you could really do kind of a Vermeer thing here with soft light”—but Connie didn’t do that. He kept it quite muted from the windows, then started underlighting from the front as if it was light bouncing off the table. I was like, “That’s unusual.” About a week later we did the reverse where everyone is walking into the office to talk to Travolta. It’s a scene where his partners in the law firm are telling him they’ve run dry. Connie knew that for the reverse he was going to backlight that shot and have a really strong sunlight coming from behind [the law firm partners] that was almost blinding. So he had thought ahead about that reverse shot. He didn’t have notes about it or talk about it, but he had a plan. It really taught me to think ahead in terms of narrative and story and to consider the picture as a whole rather than just going for individual shots.

Filmmaker: I rewatched Electra Glide in Blue earlier this year and I just love that film. Do you have a deep-cut Conrad Hall recommendation for people to check out?

Zambarloukos: Not that it’s unknown, but I would say Fat City is a truly beautiful film. It was around the same time as [Gordon Willis’s work on] Klute and they’re very good films to see side-by-side. Fat City has these day-time drinking scenes and the minute someone walks into a dark bar and the door opens, it’s so bright that the light just takes over the place. I don’t know if other people were doing things like that at the time.

Filmmaker: You’re probably going to get asked in every interview about shooting digital with Branagh, so let’s skip to the next step. Once you decided on digital, how did you choose the Alexa LF? Did you test to see how different sensors rendered the black and white?

Zambarloukos: I didn’t need to test too much because I have been using a lot of those cameras on other projects. I certainly could’ve used a RED camera or a Sony camera and we would’ve gotten good results. It’s just personal taste. When the Alexa LF first came out I was really curious to try it, in particular the Mini. I’ve often felt that the 35mm-sized [digital] sensor seemed a little soft. I always preferred the RED cameras in terms of sharpness. The medium format sensor [of the Alexa LF] seemed to get rid of that [softness] problem. That size seems to be where the Red, the Panavision DXL2 and the Sony VENICE have all arrived at and to me that medium format sensor feels just right. So, the LF gave me that medium format size, but with a color space that was familiar to me. I’ve always loved the color of the Alexa. The color palette, in particular in the facial tones, is very pleasing to me.

I was curious to see how that sensor size would pair up with the large format lenses we had used on Murder on the Orient Express and Death on the Nile. So, I took the Panavision System 65 lenses and some of the Sphero lenses—particular ones, with serial numbers and focal lengths that I had used before. I wanted to see how they would fare with a 1.85 ratio and they fared really well. The LF and those lenses seemed to complement each other. It was flattering and clean and crisp, but didn’t seem to have excessive character that would take over the image.

Filmmaker: Did Panavision do any detuning of the lenses?

Zambarloukos: We did tweak them a little and it’s to do with what’s called banding. With the Spheros and the System 65s you can’t have the entire frame in focus. There’s a fall-off and you can either move that fall-off up [higher on the lens] or you can move it down and it really depends on your framing. With Death on the Nile, it was in a 2.40 ratio and the eyelines were quite high in the frame. We cropped around the [top of heads] so I had to move that banding up a little just to make sure the eyes were always in the sharp side. For Belfast, it was a 1.85 ratio and I [framed with more headroom], so the banding we had on Nile didn’t work, so we adjusted and moved it down. The other thing that I almost always ask for is [closer] minimum focus, even if it means the lens is slower. A lot of these lenses work at a minimum focus of about 3 or 3 ½ feet. I’d rather have it at 2 or 2 ½ feet, but to adjust that you lose maybe 2/3 of a stop to a full stop, which I don’t mind. I’d rather have close focus.

Filmmaker: Belfast has quite a few Gregg Toland-esque deep focus shots. How did you achieve that look?

Zambarloukos: It was quite simple, in all honesty. I like to test, then pick an f-stop and that’s my general f-stop for the film. As an audience member, I get a little put off when I watch a film and one shot is at an 8 and then the next shot is at a 2.8. In testing, we tried some really extreme things with Ken. We always experiment. We never just arrive and say, “We know how to make the film.” Even after eight films together there’s a process of discovery. We’ll do one test to say, “Is this the look?” and then another test to say, “But what if?” And the “What if” is always really interesting. So we tested a really, really shallow depth of field as well. It was really interesting for a second, but, particularly with long takes, became really tiresome. It almost begged for attention rather than letting you be a witness. So, we settled at a stop of about 4 to 5.6. We felt that we could achieve most of what we wanted [in terms of deep focus] at that stop with wider lenses, then we put in a hyperfocal length. Once we found that method, for certain scenes we could just lock the tilt and the pan and find a frame, which was liberating

Filmmaker: The movie has these great long takes like you just described—static wide shots with deep focus where you get to sit unobtrusively with the performance. But then there are also scenes that are the expressionistic extension of how Buddy sees the world, where church becomes a nightmare of low angles and underlighting or a clash between Buddy’s dad and a gang leader turns into a High Noon-esque showdown.

Zambarloukos: I think it’s about balance and earning those shots. You have to earn the silence or earn the camera movement. As an audience, the minute you feel like [you are starting to fidget] when you’re watching a film, it means we’ve probably overstayed the welcome of a particular technique. If we had tried to do, say, handheld during those silent moments, we’d have had nowhere to go in the riot scenes. If we had been static in the riot, then we’d have had nowhere to go in the dialogue scenes.

Filmmaker: During prep you took a scouting trip to Belfast with Branagh and production designer Jim Clay. How did that trip influence the look of the film?

Zambarloukos: One thing that became apparent to me was that you were always reminded that Belfast is by the sea. So, we said, “How can we add that element in?” You need the hypnotic nature of the Irish sea there every so often. Another thing that I noticed was everyone left their bikes or prams outside. I commented to Ken about that and he said, “Yes, we never felt the threat of theft growing up. And we had such small spaces to live in that we had to keep things outside.” We certainly saw a lot of people, as in the film, just sitting by their windows or their doors watching the world go by. I have a still that I took during that trip of someone with a radio by a window with a billowing curtain on the actual street that Ken grew up on. There was also a lot of graffiti. I couldn’t stop taking photos of the graffiti. It seems like that’s kind of the silent voice of the people of the city and we certainly wanted to include that in the film.

Filmmaker: Tell me about the sets. Buddy’s street was built near an airport in England?

Zambarloukos: The actual street was built at Farnborough Airport with just a facade. They didn’t lead into any of the home interiors. Those were built separately. We had one street but had to dress it in three or four different ways. So we would shoot out Buddy’s street, then flip things—change the signs, add a bit of dressing, put in different cars—to make it a different street. We built the two house [interiors]—Buddy’s and his grandparents’—side by side in a field in a disused school in the Sunningdale area.

******Spoiler Warning******

Filmmaker: There’s a scene where Buddy visits his grandfather (Ciarán Hinds) in the hospital and during grandpa’s single there’s a big window behind him where you can see the sun ducking in and out of clouds during a long take. Normally, that’s the kind of situation where you’d either wait for the sun to find a cloudless patch or you’d use film lights for consistency. You chose to let that scene play as is with those mid-shot lighting shifts.

Zambarloukos: I think everything we did in that scene was meant to be a little ethereal and should have a kind of magic realism to it. One of my favorite films is Miracle in Milan, the Vittorio De Sica film. It made such an impression on me. It’s been such a long time, but I distinctly remember a scene in a field and all of a sudden there is a beam of light. It’s freezing cold so everyone huddles under this beam of light. Then a cloud passes over and parts somewhere else and a new beam of light appears and everyone runs over to that one. Many years ago when I saw that for the first time it stayed in my mind and it seemed to be an appropriate thing to do in this film, to let the weather also have something to say. We shot that scene with natural lighting and practicals and I didn’t want to block all of that out. When we went outside [to get a shot] looking in through the window, Pops’s slippers by the bed are a sign that Pops is about to go to the other side. So, where you put those slippers in the frame is important. We spent time and effort to place them where we thought it felt just right. Then when we placed the two nurses next to each other they looked like angels. It was just kind of being playful with the framing, because in that scene Pops is being playful in his goodbye. I had a phrase that I thought of during the shoot. I said, “Ken, to me this movie is about the joyful participation in the sorrows of life.” That became the way that we tried to frame as well.