Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

“We Can Give Clint Eastwood His Lens”: DP Jessica Lee Gagné on Severance

Severance

Severance In Severance, workers at a windowless subterranean cubicle farm have their memories surgically bifurcated. The procedure separates the consciousness of the work self from the personal self—the “innie and outie,” in the parlance of the show—with neither retaining memories from the other half of their existence.

Listening to Jessica Lee Gagné talk about her craft, it’s hard to imagine the cinematographer not taking her work home with her. Long after wrapping the show, she’s still irked that the shade of red in a kitchen’s undercabinet lighting isn’t quite right. She’s precise enough to carry .15 ND filters, because she believes each and every lens has a very specific sweet spot and even straying a half-stop changes everything. When she lights a set during testing, she likes to watch the units go up one by one, on the off chance that she might catch a stray bit of light bouncing off a stand and landing perfectly in the space.

With Severance’s full first season now available on Apple TV+, Gagné spoke to Filmmaker about half human/half robotic zollies, getting director Ben Stiller to embrace pink for an ode to Wong Kar Wai and how each lens is its most amazing at a specific stop.

Filmmaker: Severance is a show about work/life balance where the characters go to extreme measures to separate the two. There is a certain irony to that for the crew, because there’s not much of that balance when you’re working for months on end on a television show.

Gagné: Yeah, there is none, especially when you’re working in a place you’re not from. If you’re staying somewhere that’s basically just a place to sleep and eat, you really get caught up in that work cycle and never leave it.

Filmmaker: It did make me laugh to think about the neighborhood where Adam Scott’s character, Mark, lives. It’s supposed to be this purgatory of indistinguishable duplexes, where every unit is the exact same shade of blue. The people who actually live there probably checked out the show and thought, “Oh. Our street is the epitome of a soulless existence.”

Gagné: (laugh) Surprisingly, that neighborhood was super cool. The people were really nice. It’s hard to get an entire street of people to let you take over like that. It was only for a week, but you need people who want you there, and they were great. The production designer, Jeremy [Hindle], brought us there and we were like, “Oh, we really don’t need to see other places.” It was the same thing with Bell Labs (in Holmdel Township, New Jersey), which we used for the Lumon Industries exteriors. Those locations were so perfect and we barely did anything to them.

Filmmaker: Did production settle on Bell Labs early on?

Gagné: When we were doing research, Jeremy and I actually ended up pulling some of the same references, very modern style photography by people like Julius Shulman. When we found Bell Labs it was everything that we had been putting up [on those reference boards]. The first time I saw an image of it on some blog, I thought, “This is fricking amazing.” In the pictures it was overgrown and abandoned. I didn’t know that it had been taken over by these investors, who turned it into office spaces. They bought it and refinished it, but they actually kept a lot of the look of it. If it was an actual abandoned space, there’s no way we could’ve done what we did there.

Filmmaker: I was listening to a podcast you did and you talked about how during preproduction you like to do “lighting workouts,” where you go in and basically do a practice run of lighting specific scenes.

Gagné: I do like to do a lot of testing. It’s like layers of figuring out the look, starting with camera and lenses, then production design, then you get into hair and make-up. I always tell production very early on that when the set is built I want to get in there, have fun and light. I’m constantly working in different places and working with different crews, so I don’t always get that time with the gaffer to develop a relationship and see what our tastes are and how we approach work. Sometimes the gaffer and I are creating the look and the lighting every single day on these shows and we don’t even know each other.

Often, especially when you’re doing movies, your sets aren’t ready when you’re doing tests, but on both [the FX miniseries] Mrs. America and Severance, I was able to do these tests with the gaffer. So once we get into the set, I’ll just put the camera down on a tripod and say, “OK, we’re going to do episode 5 scene 8. It’s a sunny day. Let’s just start.” We’ll go light by light, one at a time. When you start lighting you really see where you actually want things—if, for example, you want them high or not. I never really know until I get in there and do it. For the daylight scenes in Severance we used 12K HMIs. So, for a day scene at Mark’s house, we’d probably have five or six of those HMIs. For the tests we’d go one HMI at a time, put them up and angle them and then we’d see, like, what the spill was like from that light. Then I might say, “I love the little detail of light on the wall there. We should keep it.”

I don’t like it when grips and gaffers flag everything right away. I want to see what happens accidentally. These tests with the gaffer enable me to explain how I like to work. I don’t want those moments to be figured out on set. I want the gaffer and grips to embrace this process and be open to seeing how things happen when we’re just watching the lights go up. Then we mark the positioning and the colors of the lights and we’ll do that for several different looks [so that they can be recreated when shooting begins]. I’ll do night looks, day looks, blue hour looks, morning looks. It’s a couple days of testing.

Filmmaker: What drew you to the Sony Venice for Severance?

Gagné: I started shooting with the Venice on a feature a couple years ago and really loved the camera. Exteriors and daylight scenes were a lot richer than on the Alexa. It was a purer camera in terms of blacks and whites and it didn’t really impose an aesthetic, which I think the Alexa kind of does. The Alexa has a look—a beautiful, soft look, but it wasn’t what I wanted for Severance. With all of our white walls and fluorescent lighting, it was like, “How do you keep these walls looking bright and vibrant and not pasty?” I think the Venice really delivered that, even shooting it super underexposed at 2,500 ASA. I also love that camera’s [internal] ND filters. I change NDs all the time, like every second. I think each lens is its most amazing at a specific stop. It depends on what you’re trying to get out of the lens, but I get very into what stop I like a specific lens at. Sometimes I’ll even use a .15 ND to get to where I need to be.

Filmmaker: So you find a sweet spot for every individual lens? How precise is it? Are you like, “The 32mm looks best at a 2.8, but the 50mm needs to be at a 2.8 1/3?”

Gagné: Oh yeah, it’s extremely precise. I do that with the DIT. It took me a while to give up iris control, but I did on Severance because shooting with three cameras makes it impossible. I can’t carry three iris controls on me. A lens changes completely from one stop to another. It’s not just the optical quality and the depth of field that changes: the contrast changes, the aberrations change. A TV show allows a DP to really get to know lenses, because you’re shooting so many days with them.

Filmmaker: You shot a lot of the show on the Panavision C Series anamorphics?

Gagné: Yes. We had a very big kit. We had C Series for most of the lenses, but there’s a couple focal lengths where we had to fill in with some T Series and some G Series. We had a 50mm C Series lens that we called the “Silver Bullet.” The entire world of Macrodata Refinement [MDR, where Scott and his co-workers toil in their cubicles] is based around that lens. When we’re close up on faces in that space, 99 percent of the time it’s that lens. It’s such a flexible lens—I could shoot it at a 2, tt was just amazing. The 100mm C Series was also beautiful. We had a 25mm at one point, but we gave it to Clint Eastwood. I had to ask Ben, “Do you want to keep this anamorphic 25mm? You don’t like curved lines and Clint Eastwood wants it.” And Ben was like, “We can give Clint Eastwood his lens.”

Filmmaker: So, you’re basically saying Clint Eastwood stole your lens.

Gagné: (laughs) We agreed to give it to him. We could’ve kept it, but we were never going to use it. Even the 35mm anamorphic only came out once or twice on the show. For wides in MDR, we would use a 20mm H Series and a 24mm P70, the large format lenses that Panavision has, because we wanted our wides to have straight lines. We didn’t want them to feel off-kilter. That 50mm C series lens—the Silver Bullet—had a very rounding effect. I didn’t like it for wide shots, because it made everything look a little off, but it was amazing for portraits and closer stuff where you didn’t have as much architectural detail. If we wanted to do something like a medium size shot of the desks on a 50mm lens, we would use the 50-500mm anamorphized Panazooms. Those I had to shoot at an 11, but they were super straight.

Filmmaker: The moment of transition to the work versions of these characters takes place in the Lumon elevator that transports them underground. You use a “zolly” effect (where the camera simultaneously zooms and dollies) that changes the features of the actor’s face while keeping them in almost the exact same framing. How did you land on that technique to convey that shift?

Gagné: It was all about the morphology of the face of the actor changing. They become another person. So, how do you show that visually? We were shooting the interior world of Lumon and the exterior world with very different styles. The interiors were much wider lenses, with a robotic feeling and close-ups with distorted faces. Then, for the outdoors we were longer lenses and more traditional. So, the idea came up: “Why don’t we just do a zolly?”

Filmmaker: You used a motion control rig for the zollies. Was that just because it was too hard to do the move manually and have the framing of the actor as precise as you wanted it to be?

Gagné: To keep the top and bottom of the frame even the whole time, the move had to be so perfect. Zollies are really tricky, especially if you’re doing them over a short distance. My first instinct was to do it on the Bolt, because I thought the move needed to be really fast, and it did end up needing to be fast. We were also just trying to work out what speed Ben really wanted it at. Ben likes to improvise and change things, but you can’t improvise with a tool like the Bolt. It takes too much time to set it up if you change your mind. I just didn’t know how we were going to be able to do it and make Ben happy and have it not cost a fortune.

Somebody pitched Anthony Jacques to me during prep. He operates the Technodolly for [the New Jersey gear provider] Monster Remotes and has a rig called the Cooper Motion Control. He developed it for a zolly in The Wolf of Wall Street. It’s a laser-driven half human/half motion control set up. He uses a computer software—it looks like a weird Excel table with a bunch of numbers in it—that he’ll connect with a laser that tracks on the ground that’s attached to a Fisher dolly that the grip will push. The [Cooper rig] controls the motor that’s on the zoom, so as the grip pushes the dolly, the lens zooms.

Filmmaker: So, basically, the dolly is pushed by the grip manually, then this Cooper system automatically adjusts the zoom’s focal length to compensate for the dolly’s speed in order to keep the actor’s face in the same spot in the frame?

Gagné: Exactly. It became a really good creative tool for us. It allowed us to completely improvise without having to reprogram something every single time. We did all those shots on a 19-90mm zoom. We did the zollies a little bit differently in episode nine, where we did some of them on Steadicam.

Filmmaker: Before we get into the lighting of the Lumon offices, let’s talk about the characters’ external environments. The lighting in Mark’s house is so minimal. It’s usually a single lamp, a television or maybe the light from his fish tank.

Gagné: Mark’s house was a fun one to do after spending so much time in the world of MDR. We put in all these weird blue practicals for streetlights on his street and also peppered them into the town in different places so you could still feel [the presence] of Lumon. When it came to the interiors, the light was very much driven by the characters. Being the kind of depressed guy that Mark is, the only reason there would be a light on is that he needed it to see. It’s not like [Mark’s sister and her husband] Devon and Ricken, where their environment is about creating a warm place and this illusion that everything is nice and cozy with all this tungsten decorative lighting. Then with Cobel [the Lumon boss played by Patricia Arquette], she almost never has light on in her apartment because she’s constantly hiding. So, a lot of the lighting (in the exterior world) was very narratively driven.

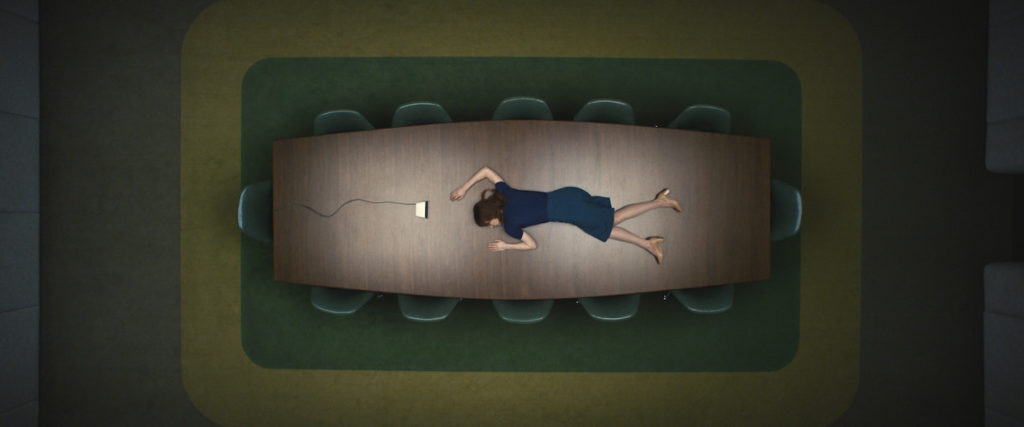

Filmmaker: The opening shot of the series is a bird’s-eye view of Helly [played by Britt Lower] awakening on a conference table for her first “severed” day at work. There’s a similar angle later in the MDR looking down on the bank of cubicles in the center of the room. Did you have a removable portion of the ceiling for those sets or did you cheat those shots somewhere else?

Gagné: There was a removable portion. That was a big conversation, because that desk is like a $100,000 desk and it’s bolted down to the ground in the stage. Also, the idea of ordering that much green carpet to move that MDR overhead shot somewhere else was just not going to be an option. Ben always said he wanted to do a high angle shot, so we knew when we built that set that we would need to lift a portion of it. We shot those on a 14mm. We tried to avoid using that lens as much as possible, but I couldn’t get the camera high enough [to use a longer focal length].

Filmmaker: For the MDR set, you put a SkyPanel above each of the ceiling’s square sections. Did you use SkyPanels for the rest of the sets’ overhead lights too, like in the labyrinth of hallways?

Gagné: No, that would’ve cost a fortune. We had half a mile of hallways. The hallways were mostly LED Lekos and, at one point, we ran out. I remember Kurt Lennig, the gaffer, saying, “Yeah, we’re going to have to start using something else.” So, he made these LiteMat RGB things that would fit flush into the overhead fixtures. Those were actually great, because there was less spill to control. I fought for everything to be RGB except for a couple things, and those things really bothered me. The bathroom wasn’t RGB and the undercabinet lighting in the kitchen wasn’t RGB, and that always annoyed me because I felt like it was a little redder than the rest of the lighting.

On the MDR set, because we knew that we were going to do lighting effects like the lights turning on and off, we had to have dividers between each SkyPanel. If we didn’t, you would have all this weird, ugly spill. And for the Music Dance Experience scene [in episode 7, pictured above] we knew we needed to be able to have isolated colors. It was fun to do the color for that. Ben gave us the music and, as a starting point, all I gave Kurt was the colors to work with that I thought would be cool. It took so much time for the dimmer board op to work on it. He could only work on that sequence when we were shooting on other stages, because there was color light spill if you were shooting in the hallway set [housed on the same stage as MDR] and you would feel weird color highlights. In the end he found a really cool pattern to it.

Filmmaker: The Egg Bar is another scene in that space where you get to ramp up the color.

Gagné: I wanted it to feel a bit like a Korean spa vibe. I wanted the kitchen to be pink, which took a little convincing for Ben. He doesn’t love pink, orange or yellow that much. I always thought of the scene between Adam and Britt in the kitchen as their love scene. It’s this weird, intimate moment between them and I really wanted to make it like a Wong Kar Wai love scene. Because the show is so minimal in terms of lighting in those spaces, every time we had a moment to do something different we fully cherished it.