Back to selection

Back to selection

Prismatic Ground Year Two: Documentary Waves

In the introduction to their co-edited collection Documentary Across Disciplines, Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg articulate contemporary documentary practice not as a category or genre, but “an attitude – a way of doing, engaging, and creating that accords primacy to the multiple and mutable realities of the world.” Emerging from the Berlin Documentary Forum, the collection embraces a vision of global documentary that spans “film, photography, contemporary art, anthropology, performance, architecture, cultural history, and theory.” If this sounds like a lot—it is, because it is. Still, rather than become amorphous in the ways terms like “glitch” or “expanded”-as-an-adjective have become, documentary retains a crucial connection to actuality, even while questions of uncertainty and authenticity remain paramount.

The sprawling and wildly ambitious second edition of Prismatic Ground (taking place May 4-8) is clearly committed to documentary across disciplines. Launched last year as a virtual festival, Prismatic Ground pivots to a hybrid model this year, with events taking place at the co-hosting Maysles Documentary Center, as well as the Museum of the Moving Image and Anthology Film Archives. For non-New Yorkers, most films in the programs (entitled “waves”) are also available for streaming during the festival’s five-day duration. This year’s edition has exploded from last year’s relatively modest four waves into an overwhelming panoply of 13, ranging from 40 to 210 minutes (!!!), as well as in-person only opening night, centerpiece and closing night programs.

Centered on experimental documentary and avant-garde film, each wave takes a somewhat thematic focus, though the titles suggest something more oblique (wave 1: look at that round ass shit; wave 3: memory of memory; wave 5: after months of total darkness; etc.) Creatively curated by Inney Prakash, each wave’s films speak to each other from quite different formal terrains. Numerous short films precede features; silent, abstract films play alongside talking-head portraits of individuals. If audience members are looking for a consistent mode documentary (or experimental) practice, they have come to the wrong place.

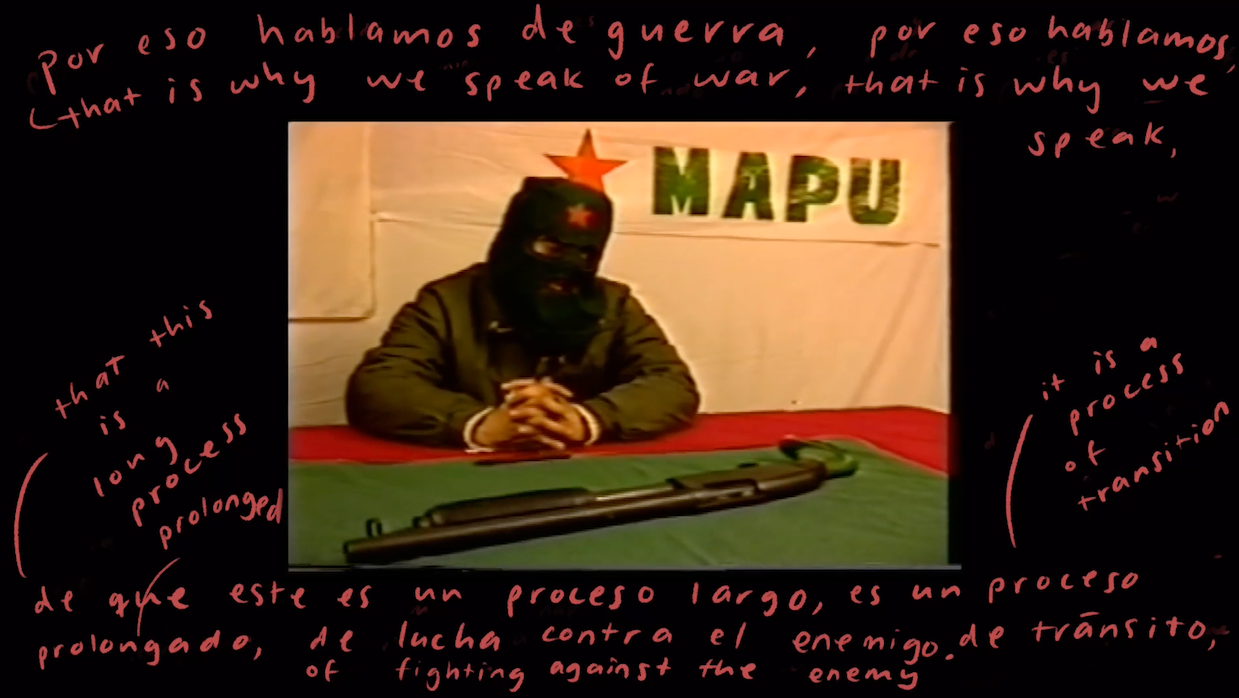

Some of the most exciting work in Prismatic Ground is also the most confounding, of which “Wave 3: Memory of Memory” is emblematic. Camila Galaz’s Vecino Vecino presents a complex form of archival activism, beginning from degraded video footage. The camera sits in the backseat of a car while a man whose face is obscured in shadow speaks Spanish. A woman’s voice provides a live translation in English, setting the scene as July 1986, a day when a cameraman is accompanying the driver to witness daily activities of the Lautaro (MAPU Lautaro) youth movement, a guerilla resistance organization during (and after) the Chilean military dictatorship. The video shifts to a different man sitting on a couch with his arms crossed, a subtitle identifying him as “Gabriel Valdes, Démocratie chrétienne.” He speaks English while a French translator speaks over him. The footage comes from a French documentary about MAPU Lautaro and is the first—and most simple—of a series of alterations over the course of the film’s 21-minute runtime. Vecino Vecino moves through a shot-by-shot visual analysis of documentary footage before the frame is invaded by rapidly scrawled pink text defining key Spanish terms overheard in the footage. Later, contemporary studio reenactments of precise movements in the video footage disrupt the authenticity of the historical documentary with implied staging and performance. Additional Instagram Live footage of 2019 protests fully enmeshes the viewer in a trans-historical, multimedia dialogue with alternative forms of power and protest.

Titled after a line from Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Miatta Kawinzi’s SHE GATHER ME works across analogue and digital media forms to reflect on sonic, textual and visual evocations of the African diaspora. The film immediately establishes a sense of multiplicity and dislocation as the frame is filled by a shot of train tracks whizzing by; overlaid on the right, a smaller 16:9 frame displays a shot of the ocean rocking back and forth. Meanwhile, a voice softly sings on the soundtrack, “dat ol / black gal / keep on grumblin’” as the lyrics appear on the edges of the larger frame. (End credits explain the song is an interpretation of a Black American work song for railroad spiking archived by Zora Neale Hurston). The image vanishes, leaving a breathy soundscape as fractured words spread across the screen like written poetry. When images return, multiple frames that were overlaid are now side-by-side, creating a dual channel separation that is nonetheless intimately interconnected. With footage from South Africa, the Dominican Republic and several locations in the United States, Kawinzi carefully constructs the transformation of stable ground into something more, um, prismatic.

Various modes of portraiture emerged across the waves, of which Younes Ben Slimane’s We Knew How Beautiful They Were, These Islands is perhaps the most evocative. Shot in deep chiaroscuro reminiscent of Pedro Costa, Slimane showcases the labor of a lone gravedigger. The man never speaks, though he does acknowledge the camera when revealing personal objects of the deceased. There is at least one completely startling moment amidst this object study where the tone of mournful isolation skirts the edge of horror. At the same time, Slimane refuses to psychologize his subject, preferring instead his tools of light and time to speak volumes.

Paige Taul’s Goat is a lovely micro-portrait of a young girl and her basketball sneakers, namely mid-top retro Air Jordan 1s. In 16mm black-and-white cinematography, the girl carefully describes the sneaker design before confidently commenting on girls becoming more interested in sneaker culture and the overall versatility of the shoe. Does she wear the shoe, or does the shoe wear her? Though it feels slight and understated, Taul’s shots of the girl leaping off the ground, trying desperately to reach out and touch the net, suggest the power and promise of self-confidence.

Rajee Samarasinghe’s Strangers takes a more reflective tone in portraying the reunion of his aunt Kamala and mother, who lived with Kamala in Sri Lanka after being sent away from her own parents and siblings for a number of years as a child. Samarasinghe shows Kamala as herself but recasts his mother as a young girl, perhaps the age at which she first arrived to Kamala’s home. Early on, the film shows one old photograph of the “real” aunt and mother together; however, for the rest of the film, the figures remain apart, rarely (if ever) sharing the same physical space, an effect enhanced further by anamorphic lens distortion, while another moment in which they share cinematic space is abstracted via reversal film stock. Meanwhile, Samarasinghe highlights the changing landscape of Sri Lanka with an unexpected color sequence along with recurring motifs of broken reflections, decay and death. Strangers is difficult to pin down but, taken as a film portrait of both individuals and their landscape, it conveys a clear sense of abstraction and alienation.

Like Vecino Vecino, Michael McCanne and Jamie Weiss’s A Minor Figure unfolds in fascinating, unexpected ways. Asking “What happens to the person history forgets?,” the film tells the story of a “he” who arrived in New York from a plane in Tokyo. A woman narrates in Japanese as various archival documents (passports, photographs, innocuous location footage, etc.) pass by on screen. “He” buys a used car from a salesman in the Bronx who remembers him as quiet and friendly. “He” wants to see America. As the archival images pile up, revealing maps, hotel rooms, and, eventually, explosives, the tone becomes eerily disquieting. What emerges is an event and a person I was unaware of—yet, for so much of the 17-minute run time, A Minor Figure comes across as a familiar, almost routine exploration of America and its mythology, wondering how ideologies become deeply embedded in spaces, cultures and individuals.

A Minor Figure’s archival impulse is apparent throughout a number of waves. Jason Osder’s Condition/Decondition highlights three short films found in the Navy Motion Picture Archives (1939-47) of subjects identified as Combat Psychiatric Causalities A, B, and C. Over on-the-ground footage of sailors under attack, rapidly loading and firing weapons at assailants in the sky and on the sea, Osder uses the Manual of Military Neuropsychiatry to postulate on the actions seen. By mimicking actual battle, the manual says, soldiers become desensitized to stress and, thereby, when battles take place, soldiers respond in a desensitized way. Osder indicates the military’s strategic use of pre-enactment and representation for psychiatric conditioning without even a hint of considering the consequences. An inverse form of psychiatric conditioning appears in Merete Mueller’s Blue Room, in which participants within two US prisons take part in a “mental health experiment” by watching nature videos on loop. When one participant describes thinking about the room where he watches the nature videos when he sees glimpses of trees outside, one only hopes that deconditioning is still possible.

While it doesn’t actively recondition psychic spaces, Libertad Gills and Martin Baus’s open sky / open sea / open ground achieves maximum effect by reorienting visual and sonic expectations of space. Using distinctive blue and red filters on rapidly edited shots of sky and sea, the film’s chaotic presentation whizzes through space, adopting a subjective bird’s-eye view of a topsy-turvy world. Enhanced by a jarring soundtrack of harsh whips of air and underwater gurgles, the film unsettles representational expectations and coordinates a unique terrain for human-animal relationships. Linnea Nugent’s A Vessel, the Ideas Pass Through also starts with images of birds—pigeons in this case—and similarly quickly unsettles our expectations of the image and perceptual understanding. Elliptical and extremely enigmatic, the film initially appears as barely perceptible flashes of light, as if a flashlight is being waved around in darkness. The sounds of insects rise into a punctuating reverb, while the images become even less stable. Fluttering either through an extremely distorted lens or perhaps an image processor, nearly indecipherable images of landscapes, statues, and birds flicker in and out of sight, from darkness to light and back again. Prismatic Ground will surely be introducing many new artists to its audiences—Nugent is certainly one to watch.

Meanwhile, purely sonic, imageless narratives reveal themselves in Pablo Alvarez-Mesa’s Infinite Distances, a 25-minute soundpiece (film?) composed of found answering machine recordings. Though it takes a little while to settle in place, once some characters and themes begin to emerge (the assholery of a dude named Rob, ongoing frustration with callbacks, medical scares, missed dinners, nearly identical messages with multiple time stamps), I found myself admiring both the ambition and conceptual thrust of the piece. Longing to see and connect with people, places, persons on the other side of the phone line requires (or, perhaps, asks for) a form of visualization of something that cannot be seen in the moment. Do you imagine what someone else is doing when they aren’t there? How many times do you call before you start worrying—or stop calling? Will you ever see them again? What would that mean? For whatever it says about documentary as a discipline, Prismatic Ground’s programs time and again lead into a serious reflection on our methods of communication. What is it that we need to see or hear to connect with one another? What is it that is necessary to visualize, commemorate, and document our friends, our past, our histories? Prismatic Ground doesn’t provide one answer, which is part of what makes the festival so rich, timely, and necessary.