Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

“A Final Hurrah for Sodium Vapor”: DP Andrew Droz Palermo on Moon Knight

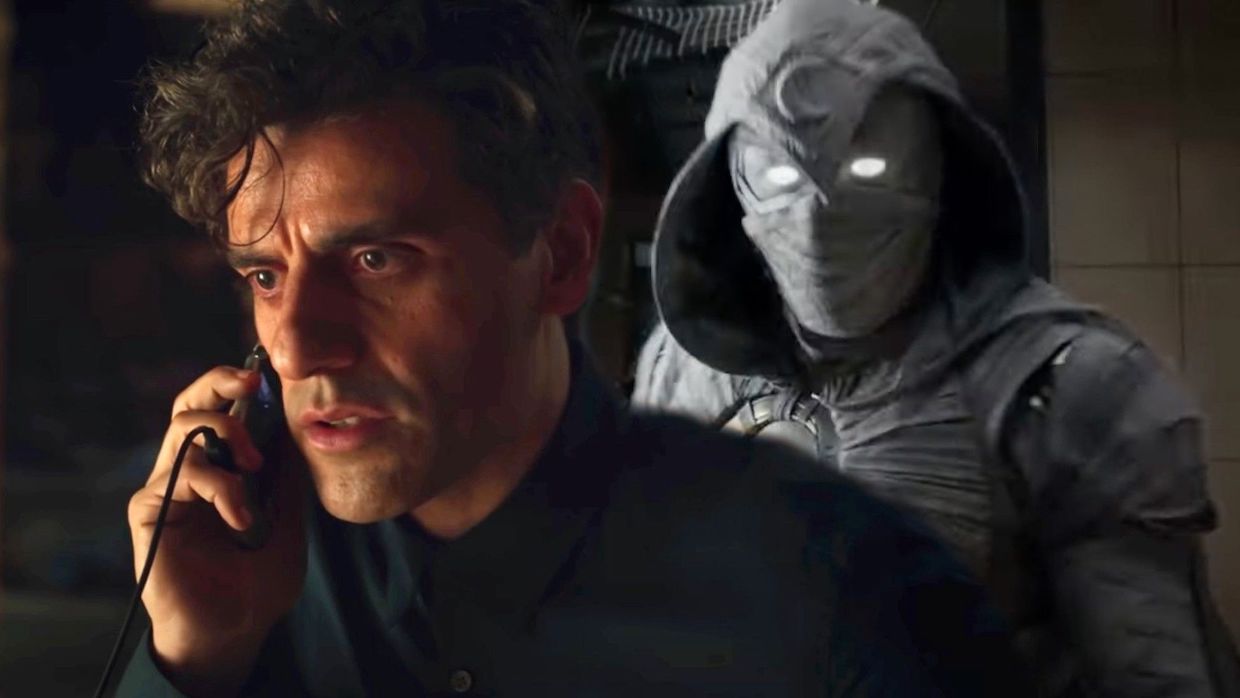

Oscar Isaac in Moon Knight

Oscar Isaac in Moon Knight When I last spoke to cinematographer Andrew Droz Palermo for The Green Knight, he detailed the learning curve for creating that film’s all-CGI fox. On his latest project, Moon Knight, the degree of difficulty has been raised from small woodland creature to towering, vaguely avian mummified Egyptian god.

The Marvel adaptation stars Oscar Isaac in dual roles as a man suffering from dissociative identity disorder who oscillates between a meek museum gift shop employee and a mercenary serving as the human avatar of Khonshu, the aforementioned god of the moon.

With the full series now streaming on Disney+, Palermo talked to Filmmaker about drawing inspiration from Roger Deakins, Xena: Warrior Princess and the Indiana Jones clones of Cannon Films.

Filmmaker: So, you’re in the Marvel Cinematic Universe now. How did you land that gig? Did you know the directors of your two episodes, Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead, before this?

Palermo: I didn’t know them, but we had a lot of mutual friends. It’s a small indie filmmaking world. I think Aaron asked David Lowery for recommendations when they were trying to come up with a cinematographer for the show, then we had a nice interview. I really liked working with those guys.

Filmmaker: Aaron was also the cinematographer on a lot of that duo’s early films [including Spring, The Endless and Synchronic]. What’s it like to work with a director with that skillset?

Palermo: It’s great. He’s got a clear sense of what he wants visually—they both do. At the same time, I could surprise them with things on set. Aaron’s a good DP. I was always happy when he’d come to me and be like, “What’s that light over there?” I knew he was thinking about it as something he might use in the future. So that was a good feeling.

Filmmaker: How much do you get tied into the previs with a character like Khonshu?

Palermo: In some of the action sequences, a lot of it was thought out before our involvement, then it was kind of our job to put our own touch on it. For anything with Khonshu, we would always have a stand-in or actor performing the role on set standing on a platform to make him really tall for reference. For the close-ups, the VFX team printed off a 3D [model] of Khonshu’s head and we’d have it on the end of a pogo stick so we could kind of animate it. For example, I might say, “Oh, I actually wanted his beak to be a little lower and I want him to be scowling at us” and they could adjust that 3D head. It ended up being a great reference for lighting [the final digital version of Khonshu]. Then we’d take [the Khonshu head out of frame] and get a clean plate. That was nice to have, otherwise you’re just off at sea on your own and you’ve got nothing physical to reference. It was really helpful for me.

Filmmaker: Where did you shoot your two episodes?

Palermo: It was all in Budapest and Jordan. We also had a unit that went to London for some stuff.

Filmmaker: How much time did you have for each episode?

Palermo: Somewhere between 15 and 18 days, with a bunch of second unit stuff. At times that felt generous and at other times it didn’t feel like enough. It’s a lot [to deal with] when you have all these action sequences and VFX. It’s just so time consuming.

Filmmaker: Did you get to use any new gear on this for the first time?

Palermo: I’d done some motion control before, but I hadn’t done it to the extent that we did on this show for the scenes with Marc and Steven [both played by Isaac]. We would use TechnoDollies to record a scene with Oscar, then take that information with all the witness cameras and the metadata from the cameras. It would go off to a third party and get programmed back into the TechnoDolly many months later and the camera could do the exact same move again [with Oscar playing the other half of his split personality]. Each of the [dual Oscar scenes] was different and unfortunately the lessons learned weren’t always applicable to [the next situation]. We’d figure out how to do one scene, then for the next it was like, “Wow, that methodology doesn’t work here at all” and we’d have to do a totally different thing. Sometimes it was as simple as split screen, as long as [the two Oscars] weren’t interacting, then it could be as complicated as the example I just laid out for you, where data is captured and then recreated at a later date for the other side of that conversation. Then there were situations when the characters hug each other—that’s its own challenge, because they’re physically interacting. Oscar was actually interacting with his brother Michael [standing in for the other role] most of the time. That was fun, to have that family element on the show.

Filmmaker: I loved the VHS Indiana Jones ripoff, Tomb Buster, that we see a few scenes of in episode four.

Palermo: That was so fun. I shot it in 4:3 on the Alexa Mini LF. I wanted to bake [that aspect ratio] in so no one could make a choice later to change it. I did some color tests early in preproduction and made some references for what I wanted the dailies to look like, then they added a bit more of that VHS chromatic shift to it [in post]. I was cackling while we were doing those scenes. A long shoot can be really hard and tiring, and it was great to shift gears into something that was so light and meant to be fun and ridiculous, where I could just go crazy with the fog machine.

Filmmaker: Did you shoot much more than what ended up in the show?

Palermo: We did a little more than what is there, but maybe only a minute more of footage if it were edited. A friend of mine, Todd Rohal, made this thing for Adult Swim called M.O.P.Z, where he made a whole feature that’s just fast-forwarded. That was how it was meant to be seen when it was aired on Adult Swim, all in fast forward. I wish that we had the time to do that with a whole feature [of Tomb Buster] because it just would’ve been so fun.

Filmmaker: Did you go back and watch any of the 1980s Indiana Jones rip-offs for reference?

Palermo: I looked at a bunch of stuff. I found this film, actually, that’s like an Indiana Jones Cannon film. I can’t remember the name of it, but the production value was insane. There was a whole sequence in which the heroes are getting boiled in a giant pot. [I believe Andrew is referring to the Richard Chamberlain/Sharon Stone vehicle King Solomon’s Mines.] I also grew up watching Hercules and Xena: Warrior Princess on TV and those had to be done so quickly and so cheaply. I didn’t revisit them, but they were certainly in my mind. Anything Indiana Jones adjacent was just perfect, because there were so many things that came out right after thinking they could capture the same lightning in a bottle.

Filmmaker: In episode two, tell me about the extended sequence in the town square. You have this nice color contrast between warm streetlights and green from the nearby buildings. Is that location a practical spot in Budapest?

Palermo: It’s a small factory location in Budapest that I think was reminiscent of some areas in London. I’m not too versed in London, I don’t know it super well, so I really relied on people to tell me when certain blocks felt authentic to London. Budapest is such a hospitable place to shoot. We had many city blocks at our disposal at night, including many of the building’s interiors to put lights. I had a Condor at every single end of every alley and balloon lights overhead. The scale of the nighttime exterior for that sequence was just huge.

The amount of light that we needed took a tremendous amount of work. I really like that sodium vapor look that is kind of fading. Everyone is moving to LEDs at this point, so it felt like a final hurrah for sodium vapor. I tried to offer color contrast, because it’s the first time we meet Mr. Knight [the superhero version of the British Museum worker side of Isaac’s split personality]. Everyone is so accustomed to Mr. Knight and Moon Knight being [in white suits] that I didn’t want to have them go sodium vapor orange. So, when they have that first conversation together, they’re in a pool of a bit more neutral light, with the warm and the green light behind them.

Filmmaker: That episode also has a storage unit location that seems like it would be a nightmare of shiny reflective surfaces.

Palermo: For the overhead lights that flicker on and off, I tested a lot in preproduction to find the right lighting units. I had certain parameters: I needed them to snap on and off very quickly, but also to be very bright. We put in, I think, 100 lights throughout the storage unit. The art department helped by making fixtures to hide them. We lit up two full rows and a couple columns, then kept using that same run. Oscar would run one way in one take, then I’d pull him down the opposite direction—just a lot of cheating there. Then the interior of Oscar’s storage unit was a build, when he’s talking to himself in the reflection on the wall. It’s a testament to the scale of these projects that there’s time to be able to test all these things in advance. I tested the reflectivity of a bunch of different surfaces. We knew that we wanted it to be metal. Stefania Cella, the production designer, put on a series of coatings in preproduction and we tested them on camera. I really like it in the show when his reflection is not perfectly clear. There’s some other effect—some haloing, or the mirror is broken, or he’s reflected in water—and it’s a little hard to see. That feels more like what reality might be and reflects his mental state as well. I was always looking for things that had a little more texture, and thankfully I had the time to test and find that perfect amount.

Filmmaker: You said you used 100 lights. What were they?

Palermo: It was a kind of Par Can.

Filmmaker: You went with non-LED units for that?

Palermo: I needed the light to be really hard and really bright, because I wanted the falloff to be significant from one light to the next. I love the SkyPanel and it can snap on and off from zero to 100 in an instant, but it’s so soft that I felt that you couldn’t get separation as they’re walking down from one light to the next. It also just didn’t feel authentic to this space to have a square SkyPanel, and what kind of housing could you make to hide a SkyPanel? So, I thought an older light would be better and it also offered that brief moment when the light is cooling down and it goes super warm before it goes off, which added a little more contrast.

Filmmaker: For the Alexander the Great throne room set, you have this strong top light coming from an opening above, similar to the Round Table chamber in The Green Knight. That set is impressive. It doesn’t look like much of it is a digital set extension.

Palermo: It’s all real. That was a full set, 360 degrees, with incredibly detailed work from set dec and production design. I had the brilliant idea, which made everyone’s life hard, to put lights underneath the set to send caustics onto the ceiling. So, the whole set had to be elevated four feet and needed to be load bearing, with all of this water on the set too. I’m thankful for the production team for even supporting that idea. Then I tried to get a nice amber, golden feeling, because there’s all these jewels and treasure in the space. That was a really tough space to shoot in, because there were so many layers and all this fallen rock. Just getting the camera to move around in there was so tough.

Filmmaker: At the outset of episode four, you have a night desert exterior. Tell me about lighting that when you’re motivating with a sliver of moon and a few vehicle headlights.

Palermo: The challenge that Aaron and Justin laid down was to make it feel like you can’t see a thing when you’re not in the light of the headlights. In reality, in the desert when the moon is full you can see quite well once your eyes adjust, but I wanted it to feel like a moonless night. Khonshu is now no longer a part of Isaac’s life, so the moon shouldn’t be around. I remember reading an issue of American Cinematographer about No Country for Old Men and that great scene where Llewelyn [Josh Brolin] is running from the truck. I revisited that article and [the film’s cinematographer] Roger Deakins talks about doing some atmospheric lights where he was just lighting the sky to offer a bit of contrast. I tried some of that, but it wasn’t as effective as when Deakins did it. I didn’t have enough atmosphere in the sky. I don’t think there was enough humidity that night.

We did a giant moon box with full grid overhead on a giant construction crane that could reach out way over the truck. I think it had something like 64 SkyPanels in it and everything was on a dimmer—definitely one of the biggest rigs I’ve ever had. Ringing the perimeter of that were Condors. each with their own (SkyPanel) 360s, so I could always add at least an edge and some soft fill from above. I really tried to push how far we could get away with underexposure in post production. It was quite bright on the day, but I was pushing it down with the DIT, because I really wanted those headlights to feel super bright when [the archaeologist played by May Calamawy] was in them and quite dim otherwise. I wish I had another crack at it. I learned a lot of lessons about how to do those things, and also how VFX can do so much to help you by erasing lights. I don’t think I leaned on that enough. I could’ve put a light or two in plain sight and they could’ve come in and just erased it for me in post and I could’ve had a little more contrast. Someone sent me a meme from Twitter which said, “I really loved this [desert] scene from Moon Knight episode four. These shots were my favorite.” And it was just four black frames. [laughs] I thought that scene was actually pretty bright, but that was funny.