Back to selection

Back to selection

“The Film Is Full of Ghosts”: Diana Bustamante on Her DOC NYC-debuting Our Movie (Nuestra película)

Diana Bustamante's Our Movie (Nuestra película)

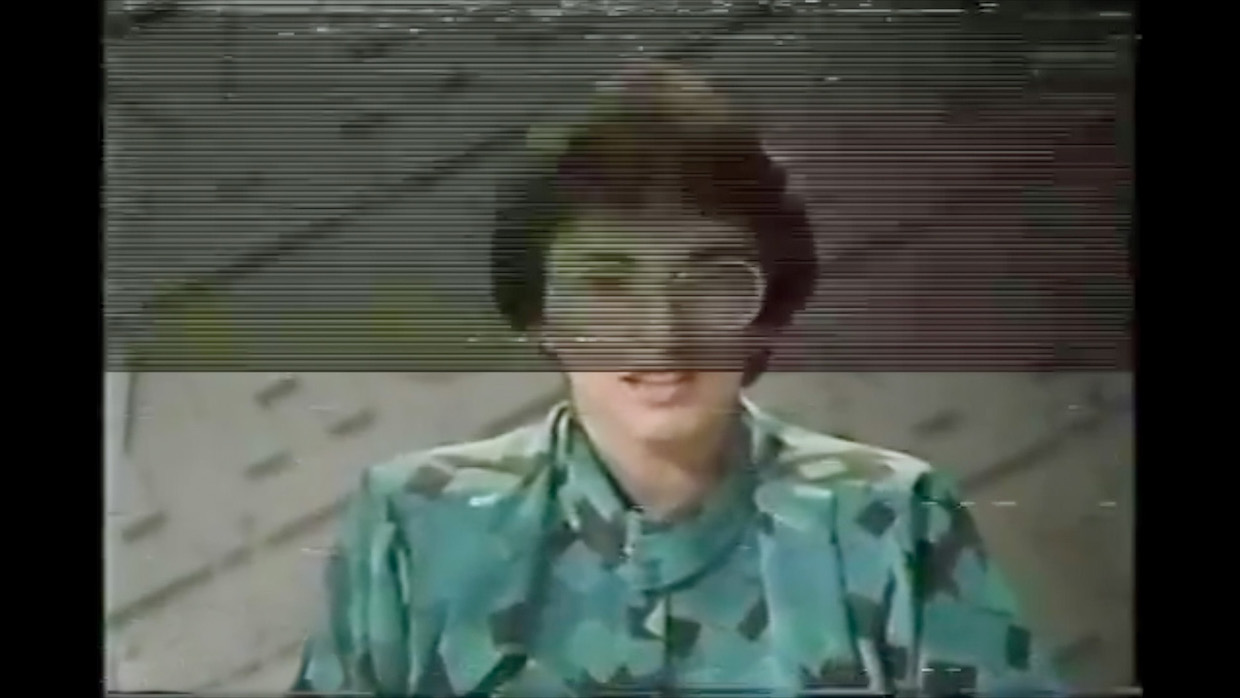

Diana Bustamante's Our Movie (Nuestra película) Diana Bustamante’s Our Movie (Nuestra película) feels like both a departure and a homecoming for the Latin American producer credited on numerous Cannes winners, most recently Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Jury Prize-awarded (and Tilda Swinton-starring) Memoria. Comprised entirely of news footage from the Medellín-born Bustamante’s childhood—who grew up in the ’80s and ’90s when kidnappings, political assassinations and blood-soaked streets were as common as choir practice—the “essay documentary” is, as the producer/director puts it, “a collage of images, repetitions and memories, built through the intervention of the Colombian news archive.” And what a visceral collage it is—from closeups of bullet holes to a zoom in on a chic high heel (never to be worn again). Perhaps the filmmaker is trying to divine something from the detritus of her past?

Indeed, left with more questions than answers lingering long after the credits have rolled, Filmmaker reached out to the busy multi-hyphenate (who also somehow found time to serve as Artistic Director of the Cartagena International Film Festival from 2014-2018) a few days before her film’s November 11 DOC NYC debut. (The following interview was translated from Spanish to English by Samuel Didonato at Cinema Tropical.)

Filmmaker: Although Our Movie (Nuestra película) is your first feature-length documentary, you’re already an acclaimed producer with several Cannes winners under your belt, most recently Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria. It struck me that Memoria, which you’ve described as “being Colombian in a profound way,” could also have been the title of Our Movie. So did Weerasethakul’s project (or any of your prior films) influence this documentary?

Bustamante: It is impossible to think of ourselves without influences, including my own work on other films, but beyond that I think there are themes that interest us more than others.

Our Movie is part of a process. Being a filmmaker is not only directing or producing, but also thinking about images—something that I was perhaps able to explore and study more as a festival programmer. In that sense, all the works I admire have an echo in me, in my work, even if they are very distant in terms of the aesthetic goals. I certainly didn’t think about it while I was making it, because creative processes are not so self-conscious. Clearly that idea of trauma, of the traza (memory), is present in a very different way in Our Movie, but this initial impulse is undoubtably present in several of the films I have worked on.

Filmmaker: I was also thinking that the “our” in the title is quite telling, as the film feels almost like an exorcism for you and your country. Was Our Movie created with a specific goal in mind? Are you hoping to achieve some sort of nationwide catharsis, or perhaps interrogate the historical record?

Bustamante: Actually, the title has many meanings that relate to the idea I want to achieve. On the one hand, I am interested in digging into the deepest meaning of the images, to remind us that this happened to us, as a generation and as a people, and that we have lived for years insensitive to pain, after a long hyper-exposure to violence that makes those images lose their meaning to us. It is through these images, which accumulated and accumulated until they lost their original meaning and became empty, that I began to understand what film I was trying to make.

The title Our Movie is also the title of a work by Luis Ospina (Cali, 1949-2019). It talks about the body dying of AIDS, focused on his friend, the artist Lorenzo Jaramillo. In my case I used this title, on the one hand, because I wanted to remember Luis; on the other, because this film is also talking about death, about another body that is suffering, but in this case it is the body of an entire society. Finally, as part of that generation that grew up in the midst of those images and that reality, I wanted to embrace that generation—my generation. A little orphaned and a little lost.

Filmmaker: You’ve said in your director’s statement, “I like the idea of intervention: to intervene. To alter images in the same way that our memories and mnemonic processes alter us: editing, creating biases and recomposing.” So, could you talk a bit about the editing process, and what did and didn’t work for the “intervention”?

Bustamante: Memory formation is fascinating because it is fluid. Memories are to a large extent a re-creation that is made through many interventions. I was interested in how these images—which in our current context we give them the value of “a reservoir of memory”—were also susceptible to this re-signification.

This idea began to take shape because there was a very particular memory I had of one of the images I used. When I had the material and was able to enlarge it, I realized that what I thought was a stream of blood falling from a stage was actually a red electric cable. I then wondered about the normalization of blood—why it was easier for me to remember a stream of blood, which did not exist, than to see something less macabre and as obvious as a cable.

It was there that the idea of intervention and enlargement took on more force. The enlargement is an attempt to direct the gaze, but it can also take it to another level of non-obvious reading, something much more abstract. In the editing process, the choice of material had a lot to do with that too, with what acquires a completely different meaning when enlarged; not because it reveals “proof” or something like that, but because what you get back is no longer an image, but an idea.

Filmmaker: I”m also curious about your “deconstruction” of sound, how it fits into what you’ve called “a collage that creates the sensation of fear that surrounded our lives as Colombians for decades even today.”

Bustamante: Last week, the film was seen for the first time in Colombia at the International Documentary Film Festival. Seeing it with this audience for the first time was very important for me, to finish understanding the film I had made.

The sound is charged with something that I was thinking about a lot, and it was fantastic and haunting. The film is full of ghosts and moments where the density of the sound moves you to another place, which is clearly not the news, but the weight of those images. They are like “gaps,” like a break in the narrative, or at least that’s how I wanted to build it through the sound.

The sound design was thought of in two ways: First, to maintain that “roughness” of the material, never trying to make it cleaner but on the contrary, to preserve its deterioration (which in the case of the magnetic archive has many sound “ghosts”). This was because the nature of those materials was not conservation, but reuse. I used those sound “ghosts” as an expressive part, and they helped me to create those moments where I was interested in taking us to a place of fear—where we do not fully understand what is being said, but there is an oppression, a weight through the sound. The beginning and the end of the film are made with the same materials, but the construction of the sound tries to achieve that idea of fear, of something ghostly as well.

The sound designer Waldier Xavier was an incredible partner in the “anti-technical” ideas that I wanted to try with the material, as was the editor, Sebastián Hernández, who had to deal even more with my experimentation. Between the three of us, we achieved exactly what I was interested in with the image and the sound. A sort of more plastic, more material expression of the material as a total body.

Filmmaker: Repetition is a major component of this “essay documentary,” even though repetition is actually a desensitizing mechanism, a means to normalize violence. Are you ultimately reclaiming or reinventing Columbia’s history through its use?

Bustamante: Our Movie is not a historical film in the sense that we usually understand history. Although all the material refers to a very specific period and events in the recent history of Colombia, I deliberately left out many other events of the same years—such as the bombings or drug trafficking—precisely because I wanted to focus on the idea of accumulation, and I wanted to return to human beings.

I didn’t want a single character to become the center of a material that is full of people who are no longer there, and who have no relationship to any particular person or to trafficking. That idea about Colombia seems simplistic to me. That’s why, as the story is constructed, what I do is select. In that selection and accumulation, those images begin to lose their meaning, and the connection with the victims. They become statistics and cease to have names, instead they become numbers and piles of things—of bodies, shoes or coffins. That accumulation that we see happened to us as a society, but it happens all the time in the world. The hyper-production of images does not result in them making more sense today, but perhaps the opposite. It is like pornography, a repetition that leads to the emptying of meaning. In that sense, it seems to me that we can read them in another way, return to them with other questions.