Back to selection

Back to selection

“To Change Reality, You Need to Change the Narrative”: E Mãlama Pono, Willy Boy Director Scott W. Kekama Amona at Hawaii International Film Festival 2023

E Mãlama Pono, Willy Boy

E Mãlama Pono, Willy Boy At the end of the recent Hawai’i International Film Festival, Filmmaker reached out to director Scott W. Kekama Amona to learn more about E Mãlama Pono, Willy Boy, which won the festival’s Audience Award for Best Short Film. An astonishingly assured, measured debut, Willy Boy is one of the more important Native Hawaiian and indigenous titles to come out in recent years, successfully addressing issues like land-rights injustice, political disenfranchisement, police overreach and native identity in a concise narrative framework that takes place in only one day, from one character’s awakening to their eventual “awakening.”

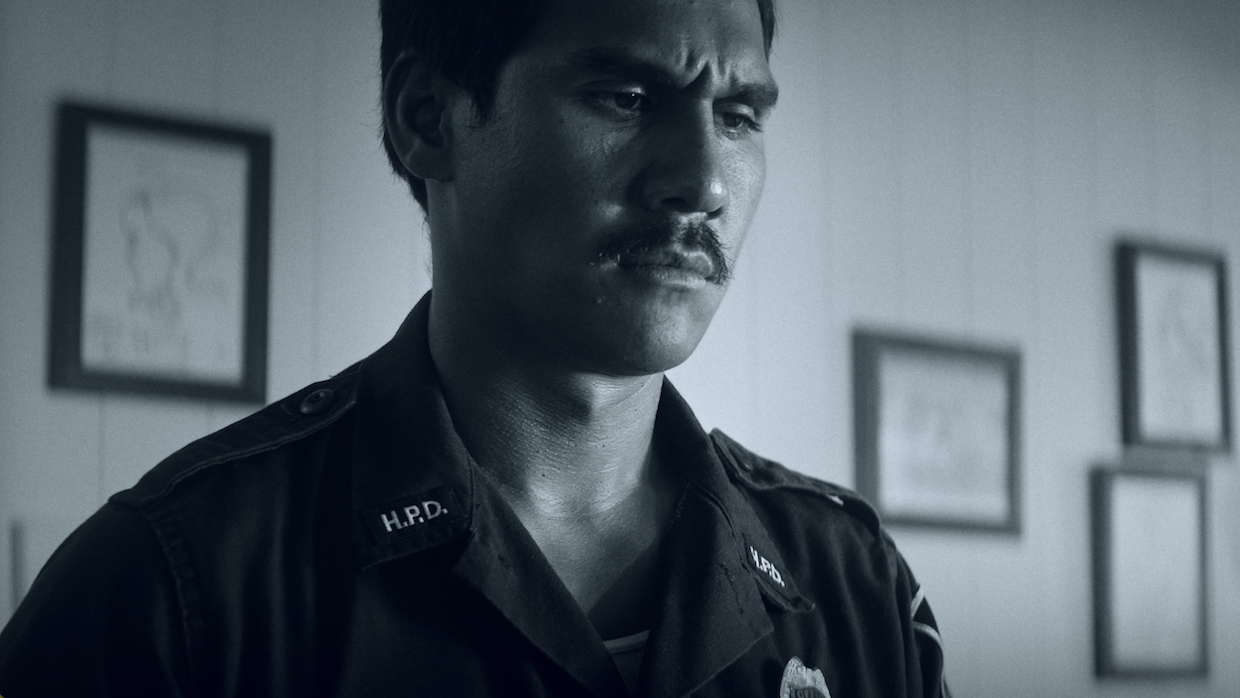

Shot in a steely, timeless black-and-white by cinematographer Chapin Hall (Out of State, Every Day in Kaimuki), the film follows a Native Hawaiian police officer assigned to evict the mainly Native Hawaiian residents of an unauthorized encampment; caught between his job, his overly enthusiastic partner, and a family member on the other side of the protest line, he must decide what is legally—or ethically—”right.” Hawaiian audiences will undoubtedly be familiar with the the imagery and agony of several decades worth of Hawaiian land-rights struggles and protests that Amona draws upon, from Kalama Valley to Sand Island to the recent Mauna Kea gatherings, but one doesn’t need familiarity with the island’s history to be impacted by his skillful summation of the moral dilemmas faced by all those living under economic and political domination.

Amona’s script, co-written with partner Nani Rían Kenna Ross, pairs that legacy of Hawaiian political disempowerment with more universal struggles against systemic racism and aggressive law enforcement, all within that controlled narrative of one day, one location. While grounded in all-too-somber realities, the film avoids the weighed-down aspect of similarly themed works, thanks to the script and directorial eye; here, even the perspective of a young girl living in the encampment is given time, with her flights of fantasy adding a sense of lightness to the storyline. Amona’s greatly assisted by the cinematography of Hall, demonstrating again after Out of State and Every Day in Kaimuki that he’s one of the most intriguing cinematographers not only “on island,” but in the American independent scene, and a cast whose talents bely their experience level; only two, Ioane Goodhue and Kawika Kahiapo, are even professional actors.

Amona’s career arc is unique, in that he’s made this debut film at the age of 60. Arriving late to filmmaking, he spent most of his career as an educator at a Hawaiian charter school. Returning to school to study film after using it to teach his own students storytelling fundamentals, he earned a degree in digital filmmaking. Amona was generous enough to offer his wisdom on the inspiration for the film and some stories behind its creation, and his own thoughts on Hawaiian cinema now. He also spoke on traditional Native Hawaiian aspects of storytelling, and how such ways of seeing are being brought into contemporary cinema.

The responses have been edited for length.

On the origins and inspration of the film

My life and creative partner Nani Rían Kenna Ross wrote the original script, pulling inspiration from documentaries around Indigenous land struggles in Hawaiʻi and the Pacific during the ’70s and ’80s. She was curious to explore the fracturing, rationalization, reconciliation and navigation that happens when an Indigenous character is put in a position where their cultural values come into direct conflict with colonial constructs, including something soul-shattering, like being a Native Hawaiian police officer tasked to evict your own family and other Native Hawaiians. Nani and I had intense conversations during the script’s development about my experiences as a young Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) male growing up during the Hawaiian Renaissance movement, witnessing our cultural and language revitalization and the political activism around land struggles against the illegal occupation of my homeland, and how these things informed my identity and directly impacted my feeling both Hawaiian and “not Hawaiian enough.” I remember watching the news with my dad growing up, and continually seeing the State and media pitting Hawaiians against Hawaiians during land struggles like Kalama Valley, Waiahole/Waikāne, Sand Island and Waimānalo, even now with Mauna a Wakea, showing division by having Native Hawaiian law enforcement juxtaposed with Native Hawaiian protestors/protectors. My identity and the narrative about my homeland was through that lens—someone else’s lens, the State and media. Seeing Native Hawaiian police sent in to deal with Native Hawaiian land issues, to evict and arrest our own people, felt like the State was sticking a knife in my gut and then twisting it too.

On why the film needed to be made now, and its roots as a proudly Native Hawaiian/Kānaka Maoli film

To change reality, you need to change the narrative. Indigenous people worldwide often deal with similar trauma and, unfortunately, Kānaka Maoli issues of land struggles are intimately linked to colonization, imperialism and occupation, so the narratives we see playing out are on repeat, like a nightmare version of the film Groundhog Day. The Indigenous Landback movement, like other movements prior, is often closely tied to art, in this case cinema. EMPWB contributes to subverting the colonial narrative, creating space to reclaim and connect the legacy of Kānaka Maoli land struggles from the past to our present and future. One of the risks I took was making the film in black-and-white because it creates a timeless feeling, so you cannot tell if this narrative is happening in the past, present or future. The black-and-white also strips away the commodification and exploitation of my homeland as a “paradise,” allowing audiences to see that Hawaiʻi has one of the highest rates of homelessness per capita compared to the US continent, and Native Hawaiians make up the highest demographic of homelessness in their own homeland, a direct result of colonization, imperialization and the illegal occupation of Hawaiʻi. This film removes the guise of paradise and the colonizer’s lens, and is unapologetically a Kānaka Maoli story that takes control and reimagines the outcome. Although I hope the film resonates with audiences outside Hawaiʻi, it really is a wake up call for Kānaka Maoli and Indigenous people to not be fooled into being divided, but to support each other.

Sometimes you have to choose between conflicting values but choosing to do what is pono (culturally right or balanced) may mean you will be criticized for your choices. And of course, the film is very relevant with BIPOCs’ turbulent historical relationship with law enforcement and systemic racism, and the renewed calls for defunding since George Floyd. It is hoped that a film like EMPWB can be a departure point for other marginalized groups to open discourse around difficult and complex issues presented in the film, and inspire change beyond Hawaiʻi.

On the creative and filmmaking process, and foregrounding Native Hawaiian storytelling tradition and culture

The bones of the story were there from the start, when it was accepted into several labs and mentorship opportunities that Nani and I attended and benefited from together, such as the Sundance Native Shorts Lab in Hawai’i in 2016, but the refinement and layering of meaning took time, and many eyes contributing to the creation of this moʻolelo (story). Meiwi are literary devices and aesthetics specific to Kānaka Maoli storytelling and literary tradition dating back to our oral tradition and the Native Hawaiian creation chant, the Kumulipo. Kānaka Maoli storytellers pride themselves on the mastery of weaving a story with these different meiwi, and one of the most common devices is called kaona, which is often defined as the “hidden meaning,” but it is more of a method of layering meaning within a moʻolelo so that as the audience matures or spends more time with a moʻolelo, the story continues to give and reveal more meaning. Layering different meiwi took time in EMPWB and we were fortunate to have both time and many different mentors and readers as Hawaiian/Indigenous and non-Hawaiian/Indigenous who offered their manaʻo (thought, idea, belief, desire) that contributed to our crafting the moʻolelo. We often thought the film would never be done because there were so many obstacles once the script was locked, from funding and casting to recasting. Then COVID hit, and impacted the production most; we shut down production several times. All this proved what our producer Justyn Ah Chong said through all the delays and challenges; “films have their own timeline and they will happen when they are meant to happen,” which is a very Kānaka Maoli mindset.

In an act of real allyship during the collaborative process, Nani spent a few hours on set the last day merely to “experience” the production; otherwise, she stepped aside in the process after the script was written and locked so my vision as a Kānaka Maoli director took priority; in fact, Nani only saw the film as a final festival cut one week before it premiered. And because I modeled my filmmaking process after building and navigating a waʻa (canoe), I was fortunate to work with so many talented and seasoned creatives that helped me navigate the waʻa, like Ah Chong, who is also a brilliant Kānaka filmmaker who brought that keen eye to our collaboration, and cinematographer Chapin Hall, who offered so much time, talent, wisdom throughout the process.

It truly took a community to bring this moʻolelo to the world, including having amazing mentors like Karin Williams and Leanne Ka’iulani Ferrer, and funders like Pacific Islanders in Communications and the Nichols Family Film Fund. I am deeply grateful for the amazingly talented and generous film ʻohana (family) that stood by my side, kept me grounded, and allowed me space to take these risks with this project.

As producers, Justyn and I prioritized and culturally invested in Native Hawaiian protocol, consultants, language and epistemology in our film practices, as a model for how films should and can be made mindfully and with sensitivity in Hawaiʻi for people and the ʻāina (land), especially as an Indigenous film project where the majority of our cast and crew were Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders. Most of the principal actors were also fluent in ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi and Hawaiian Creole English (Pidgin), which created more authentic performances that local and native ʻŌlelo-speaking audiences appreciated and have commented on.

We were very fortunate that one of our locations was set at Puʻuhonua o Waiʻanae, an actual homeless community and one of the largest encampments on Oʻahu, spearheaded by the encampment’s leader Twinkle Borge. The residents generously opened up their community for the filming. Our set designer Elias Chang did build a separate set for the majority of filming, as we were mindful not to overstay our welcome there, spending the minimal amount of time so we were not re-traumatizing the residents. However, the residents were excited to see the production and some participated as background extras and even in a speaking role, like the outstanding and authentic erformance of Keala Pacheco, who plays the passionate resident/protestor Kaniala Daniels. I cannot say enough about all the immensely talented actors in our film, whose performances exceeded my expectations. Ioane Goodhue (Officer Kupihea aka Willy Boy) is one of the few professional actors in our film, having an upcoming role in Taika Waititi’s Next Goal Wins (2023), and Kawika Kahiapo (Dennis) is the other experienced actor, having roles in several of Alika Tengan’s previous films, including his latest Every Day in Kaimukī (2021). Otherwise, most of our actors were novices and trusted me in the process to coach and support them in their outstanding performances, like Shawn Kahoʻolemana Naone, Kealiʻinoe Tengan, Hailee K-Aloha and Kalena Holani.

Lastly, we are very honored that our film was one of Leanne Ka’iulani Ferrer’s last executive produced films as Executor Director of Pacific Islanders in Communications (PIC) before she left us to be with her ancestors. It was a blessing to call her a mentor and friend all these years as she was a steadfast supporter and championed Kānaka Maoli and Pacific Islander stories. We are also honored and proud that our film not only helped sponsor an intern and several production assistants but that many crew, especially for Kānaka Maoli and Pacific Islanders, received first-time experience or leveled-up in positions in the film industry, including some of our production assistants later being hired with Magnum PI as a direct result of working on our film.

For those who wish to know more about Pu’uhonua o Wai’anae or donate to this community in need, here is their website: https://www.alohaliveshere.org/about

On the screening experience at HIFF

HIFF is an outstanding experience for filmmakers and audiences, and each year the staff does an excellent job in trying to create a unique and myriad program around their mission. The program offers not only a range of outstanding films but it is a fantastic festival for filmmakers to network and create outreach experiences, whether with audiences from the Q&As or other educational engagements, like school visits. I participated in the HIFF Guest Filmmaker Program. As a former educator, these school visits were a highlight, especially to connect with youth and teachers interested in the content of our film, Kānaka Maoli issues and/or the filmmaking process. Likewise, after each showing of our film, my producer, actors and myself participated in Q&A experiences with the other filmmakers in our Made in Hawaiʻi showcase, affording us an intimate and direct audience experience. Of course, most filmmakers create stories we hope entertain, resonate with, challenge or offer a unique perspective of the world for audiences, but for a Native Hawaiian filmmaker, showcasing in my homeland and sharing my film with a hometown audience—and Indigenous communities worldwide, via virtual streaming—was priceless and a memorable experience. I am very proud to have honored my ancestors and community in this way and I cannot mahalo nui HIFF enough for this opportunity. So many people have reached out about the film in person, through email and on social media to express how each time they watch the film, they fall more in love with it and see or pick up new things—so the kaona (hidden meanings) are working. I am very proud of this story, it is awesome that audiences recognized and appreciated EMPWB with this honor and we’re thankful beyond words.

On the upcoming Makawalu project, an eight-story omnibus collaboration between innovative New Zealand production company Brown Sugar Apple Grunt and eight Native Hawaiian filmmakers.

The Makawalu Project has been an awesome experience, and as I said during the Makawalu/Kāinga panel during HIFF, one of the best experiences of being a part of the hui (group) was the intensive week-long writing workshop based on Brown Sugar Apple Grunt (BSAG) playbook and run by Kerry Warkia, Kiel McNaughton and Sarah Kim. The hui was elated to come away with a first draft of a feature-length script and there was a special shorthand and camaraderie having Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander energy in the room that most of us had never experienced before. We truly are in a waʻa (canoe), helping each other build and navigate this film as a collective.

On filmmaking in Hawai’i, and the rising swell of Native Hawaiian, Pasifika and Indigenous work

There’s so much one could address and unpack about filmmaking in Hawai’i, especially the processes and challenges for Kānaka Maoli storytellers in the past, now and what we hope for in the future. Filmmaking is such a reciprocal process and there is a wildly talented group of Kānaka Maoli and local filmmakers here who grew up watching predecessors struggle and compete for limited resources and funding, so many of us, like other Indigenous filmmakers worldwide, adopted the motto “lift as we rise.” It speaks to our core cultural values as island people from a culture where balance, unity, care for each other and the ʻāina (land), and aloha for our world is required for survival and to thrive. Many choose to lift each other up because it is hard making a film, and we would rather kōkua (help), kākoʻo (support) and celebrate by giving each other aloha.

During the Hawaiian Media Makers Conference hosted by Pacific Islanders in Communications in 2014, Leanne [Ferrer] pulled me to the side and said: “Our time is coming. There is a rising wave of Kānaka Maoli filmmakers and we will tell our own stories and the world is going to want to hear them.” We know there is a demand for quality and authentic Indigenous storytelling, with award-winning, popular works like Sterlin Harjo’s FX Reservation Dogs and the Indigenous-led cast of Prey (2021), and more Indigenous key creatives excelling in Hollywood. So, even though it is still expensive to produce a film in Hawaiʻi and there are still struggles with funding and casting, there are also exciting new opportunities than ever before for Kānaka Maoli filmmakers to tell our own stories because narrative sovereignty is key; this is the other motto that many of us have adopted, “not about us without us.”

Consumers really do want authentic stories. There’s an incredible wave (really a swell of waves) of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander key creatives. Some of the exciting organizations outside Hawai’i helping to support Kānaka Maoli filmmakers are CAPE, Nia Tero and IllumiNative to name a few. For example, Justyn Ah Chong participated in a year-long mentorship program with Nia Tero and 4th World Media Lab, and I am participating in the inaugural IllumiNative + Netflix Producing Program. Many of our Kānaka Maoli filmmaker friends in the Makawalu Project are in various stages of development on episodic works and films, and we cannot wait to share with the world. Mahalo nunui!

Mahalo nui to Scott Kekama Amona for sharing his thoughts and wisdom with Filmmaker. We’ve italicized some of the Hawaiian phrases used here that wider audiences may be less familiar with, in order to highlight the language.