Back to selection

Back to selection

Rotterdam 2023: Three-and-a-Half Days of the Tiger

Oriana Ikomo in The life and strange surprising adventures of Robinson Crusoe who lived for twenty and eight years all alone on an inhabited island and said it was his

Oriana Ikomo in The life and strange surprising adventures of Robinson Crusoe who lived for twenty and eight years all alone on an inhabited island and said it was his I was lucky to see two films I liked upon arriving for my first IRL International Film Festival Rotterdam: with a limited timeframe of three-and-a-half days, starting strong put me in a desirably pleasant and more-receptive-than-usual mindset, even if my fortunate choices seemed mostly like beginner’s luck. The festival’s extremely public firing last year of most of its senior and longstanding programmers led, whether out of solidarity (either publicly stated or more quietly expressed via networks of mutuals) or lack of enthusiasm about the resulting lineup, to some regular attendees sitting it out. When I arrived a third of the way through, the collective diagnosis I received from colleagues who’d attended previously and been there since the start of this iteration was unusually uniform: It was harder—even more so than with previous sprawling feature slates—to find anything to get genuinely enthused about, with a decrease in the baseline adventurous works Rotterdam and Locarno traditionally focus on in favor of more audience-friendly fare, uncharacteristically bad selections in the flagship Ammodo Tiger Shorts section and fewer screenings of both purely experimental fare and projected-celluloid repertory. It’s hard to imagine that the extreme turnover didn’t factor into those weaknesses.

Partially chosen on the logic that it’s always fun to watch movies about other movies, my first screening was Mudos testigos (Silent Witnesses), assembled from the 11 hours that survive from 12 features and assorted newsreels made from 1922 to 1934, Colombia’s silent era. It’s also the last film by the late Luis Ospina, whose The Vampires of Poverty recently rocked me enough that, on the basis of that half-hour alone, his final work was a priority. “We had to go through many things, including death, so it was a rough process,” his co-director Jerónimo Atehortúa Arteaga said during the introduction, but the work itself doesn’t show the strain, structuring its archival rediscoveries as a love triangle between Efraín, his love Alicia and her jealous wealthy suitor Uribe. In three chapters (“Amour Fou,” “Days of Wrath” and the perspective-shifting “The Diary of Efraín,” in which third-person title cards give way to the protagonist’s first person voice), Ospina and Arteaga curate fascinating footage from an especially unknown pocket of world cinema. Efraín and Alicia’s urban courtship is captured on city streets by long lenses, with all the uncontrollable sidewalk life and other unpaid-for production value location shooting can bring. A shot looking out from inside the fabric store Efraín works at, with a streetcar stopping to deposit and pick-up passengers in the background, is Rohmerian in that sense.

When Efraín goes to the movies, a newsreel break explicates contemporaneous Colombian history and throws in bonus anti-American propaganda from the period (Uncle Sam is shown dragging his claws over the globe, looking more like Coffin Joe than anything). Previously largely culled from narrative features, the story is then taken over by more newsreels, first via a city-leveling fire captured on red-tinted celluloid pulsing with sinister grain against which a stream of firehose-ejected water looks like a black line. Because the Colombian footage sources are stated in the opening titles, I was slightly annoyed to find out from the end credits that at least some of this section’s images come from The Great Fire of Toronto of 1904—too much a bending of self-imposed rules, and the only sustained passage in which archival film is reprocessed by obviously contemporary technologies, an over-emphatic attempt to underline a rise in the emotional temperature by disrupting the chronological proscenium. But I also respect the desire to throw in a spectacular natural disaster by any means necessary, especially when it’s close to Peter Tscherkassky nightmare territory, and it’s a small misstep in a cinephilically delightful work.

The charms of functionally staged, floridly acted melodrama are buoyed by sweating the surrounding details, like having title cards tinted the same shade as the scenes they accompany, and by Carlos Eduardo Quebrada’s score, a superior pastiche of contemporary silent film soundtracking benefitting from an unusually large 12-piece orchestra. The third act shifts from the city to the country, thus from an urban population to rural indigenous inhabitants, in a mode that’s more hallucinatory and less defined than the preceding acts. After the story wraps, a few stingers from the sound era follow, including a priest offering a prayer that the cinema might serve God’s ends and help envision heaven on earth—a reminder that there have always been people in positions of gatekeeping power, financial or otherwise, with terrible ideas about what films should be.

There was an obvious appeal to seeing a movie about a tiger at the festival of Tigers, hence in part my second screening, Andrei Tănase’s Tigru (Day of the Tiger), a second-generation Romanian New Wave work roughly 30% faster and funnier than its predecessors; its rising-force DP, Barbu Balasoiu, shot Sieranevada and therefore is simultaneously a bridge to first-wave director Cristi Puiu and an example of his successors. After veterinarian Vera (Catalina Moga) sees husband Toma (Paul Ipate) cheating on her, the emotional hangover leads her to get sloppy with zoo protocols and accidentally unleash Rihanna, the big cat in her care, the starting point for a comedy that harvests fresh jokes from the very specific and generally underexplored environment of a zoo.

Inspired by a tiger’s real-life 2011 escape from a zoo, Tănase’s first feature takes on, then discards as convenient, signature Romanian New Wave characteristics. Most scenes are, per custom, captured in unbroken, handheld masters—but not all, with cuts for reverse shots or rhythmic emphasis where sensible. There are scenes of corrupt officials and routinely rude citizens—the harlequins and pantelones of Romanian comedia dell’arte—but also some new stock types (like the tattooed rapper-or-wannabe who owns that tiger) indicating that time has meaningfully passed since the first wave, as does the fact that there’s so little smoking that I actively noticed its absence after a while. (One cigarette is consumed, almost as a kind of narrative exhale, towards the end; I guess Romanian society really has changed.) Other degrees of difference include an unexpectedly chill score by Air’s JB Dunckel and a respect for the value of animals as animals—i.e., physical presences that are inscrutable to a certain extent, which is good for comedy—rather than merely when pressed into service as metaphors. Not to say that the tiger isn’t plainly symbolic (Tănase explains for what in this interview; I tried not to think about it while watching)—but it registers more interestingly as a real, dangerous presence. (It was shot in cages whose bars were digitally removed and supervised by tiger trainer Thierry Le Portier, who’s worked on Life of Pi, Gladiator et al.) Production and costume design details elevate potentially stock scenes, like when a young man awkwardly hits on Olga in her car while wearing a bravado-exuding Mastodon t-shirt, as does careful staging; when Olga confronts Toma about cheating, the exact moment where she says something specific enough that he goes from trying to bluff his way out to sheepishly rubbing his neck and walking away is captured from inside a bathroom, his common-enough change of physical language stylized by its refraction through the door’s opaque glass.

Animals are equally respected by Benjamin Deboosere’s The life and strange surprising adventures of Robinson Crusoe who lived for twenty and eight years all alone on an inhabited island and said it was his—a title so long it requires coming up with an alternate label for conversational purposes, even if admittedly that’s a condensation of the novel’s even more verbose frontispiece. The poster and tagline give a more succinct indication of the thematic thrust: “Robinson Crusoe was a dick.” Daniel Defoe’s once-classic novel, which I assume has been thoroughly de-canonized by now, remains obviously seductive for its archetypal crystallization of the one-man-conquers-desert-island concept but is also rancidly, unsubtly colonialist to its period bones (and, as memory serves, Crusoe is an annoyingly pious and sanctimonious type). In contrast, the 73-minute-film radiates good-natured energy from its first post-credits shot, of deaf actress Bernice Leming striding right-to-left, in sync with the camera, to introduce herself. In Dutch sign language “Hi!” is two hands waving, a cheerfully inviting gesture that, combined with the confident tracking movement, immediately grabbed my attention. Deboosere casts three black women in the main roles—the shipwreck survivor, his cannibal companion/slave Friday and the English captain who rescues both—to push back at colonialist imperatives while still taking advantage of the plot’s framework for generating memorable images (islands and beautiful oceans, man versus landscape) and its familiarity, which enables spending minimal time on explication in favor of weird jokes.

Tropical Malady used subtitles to impose a narrative on nighttime nature footage of monkeys; this pauses its main Crusoe narrative about 15 minutes in to shift attention over to inherently comical goats captured in daytime. Similarly via subtitles, the animals are given a rhyming B-plot when Gio (presumably cinema’s first nonbinary-identifying goat) is separated from family and friends. (The goats regularly recur, with one clothed in an incongruous purple tunic that’s funny every time.) Proudly flaunting its minimal practical effects and general shot-on-an-island resourcefulness, this is the kind of movie that can generate a good laugh from the disjuncture between Robinson Crusoe looking over a cliff and exclaiming “What a view!” and the vantage point from where the camera is pointedly placed, at an angle where a tree blocks access to said view. The not-so-stupid animal tricks, unexpected musical numbers and oneiric use of day-for-night make for a brisk deprogramming of its source material whose ultimate joke is that the “color-blind” casting of all-black actors in parts intended to elevate two white people over a colonial subject leads to a finale uniting three black women in solidarity.

Another approach to engaging with and defanging anti-blackness in once-venerated cultural objects came from Steve McQueen’s Sunshine State—not a film but an installation commissioned by IFFR, one of the six on display this year. The two-channel work begins rather than ends (it’s hard to tell with loops!) with a prelude of two images of the sun: one a static view from afar, the other slowly zooming towards its center, the increasing roar from both eventually joined by McQueen hoarsely, repeatedly whispering the title. The bulk of the installation takes its audio from McQueen retelling an anecdote his father told him shortly before dying about a racist confrontation in the ’50s. That one recording is played three times, and with every repetition more of the story is stripped out, leaving clipped words and phrases as markers of where we are within it. Paring a traumatic experience down to shorthand, where a few keywords are sufficient to trigger flashbacks, is a very workable metaphor for memory.

The visual component for this main section comes from 1927’s The Jazz Singer, the first (part-)talking feature, which I suspect most people (myself included) have only experienced as a minute-ish clip in film-history-montage contexts of Al Jolson singing “My Mammy” in blackface and promising “You ain’t seen nothing yet.” Since Jazz Singer isn’t required viewing like The Birth of a Nation is (was?), it’s unfamiliar and ripe for exploration, and McQueen applies several kinds of visual intervention to both those famous moments and less familiar surrounding scenes. The most unnerving involves simply erasing Jolson’s head altogether while he’s in blackface, leaving only a moving silhouette of negative space; this draws heightened attention to an upsetting image by its conspicuous absence, replacing it with a different kind of “black” face and literalizing Ralph Ellison’s invisible man. In tandem with the increasingly pared-back audio, McQueen’s installation models two complementary ways of processing historical racisms. While I was watching, a woman came in with her pre-adolescent child and answered her questions in a discreet whisper. “That’s awkward,” I thought, then realized that—as a seasoned gallery artist well before he was a filmmaker—McQueen probably knows that museums attract families with children regardless of what’s currently on and could have foreseen his work acting as a conversation starter between parent-and-child, a catalyst to mirror the father-son interaction it describes.

Credit where due to Dea Kulumbegashvili, the other name auteur with an installation at IFFR: she’s never made gallery work before, but her Captives is a whole-ass installation (originated at Tabakalera) rather than a weakly reformatted single-channel experiment. The floor of a black box room is covered with some thick plexiglas reflecting the screen above; underneath, an aluminum sheet rumbles unignorably whenever the audio gets especially loud. A long static shot of an unoccupied living room, with an open doorway frame allowing a view of part of the bathroom behind it, is punctuated by “outdoor” sounds as a prelude to some kind of grotesque humanoid dragging itself into the frame and over to the sink, then relocating to the living room chair and finally walking straight into the lens. The human-less portion fulfills some of slow cinema’s traditional mandates: the longer you stare, the more detail is perceptible in the wallpaper paneling, beams of constructed sunshine hitting the room itself, levels of reflectiveness on different surfaces and so on. But Kulumbegashvili’s big disruptive introduction here is the overtly CG wrinkled nude that sighs like it has a terminal illness. As with the end of Beginning (spoiler alert, obviously), where a character slowly dissolves into dust, Kulumbegashvili embraces flagrant computer animation, theoretically producing new frissons within a mode that prioritizes the construction of total realism. In practice, while the impulse to keep pushing forward is laudable, Captives seems stupid, which is probably just a question of sensibility; the figure’s vaginal lips look like a clay add-on from a poorly fired kiln or a horribly and unintentionally kitschy reject from Guillermo Del Toro’s conceptual sketches.

Another kind of divisive auteur experience began with watching Ulrich Seidl having his photo taken on the modest red carpet inside the Pathé multiplex which serves as one of IFFR’s venues, then introducing the world premiere of WICKED GAMES Rimini Sparta to the friendliest audience imaginable. Seidl has been courting controversy since film school when, in his own telling, thesis project The Prom got him kicked out—but, even by those standards, having your world premiere canceled days before is a different tier of shit. A report in Der Spiegel accused the director of traumatizing child actors during the production of Sparta, the second part of a diptych about two brothers. The first, Rimini, premiered at the Berlinale in 2020, but Sparta had its TIFF 2022 premiere pulled after the report; Seidl pushed back with his own responding statement (many articles and investigations have followed since), and other festivals have since programmed it, but the reputational (or at least optical) damage seems to have been done for the moment.

Seidl originally conceived of the Paradise triptych as one super-long work before being diverted away from that, either by festival rejections or his producers, but given the situation, there’s seemingly no reason for him not to revisit that dream and recut Rimini and Sparta into one huge, essence-of-Seidl object as long as it could find a home. IFFR has a history with Seidl, moderator Olaf Möller said in his introduction, and the audience certainly acted like he was a returning hero, not least during the carefully stage-managed Q&A afterwards when Möller asked questions, “ran out of time” to take any from the audience, then relented and took precisely one from a friendly party (asked in German, no less). The Sparta fallout doesn’t seem to have moved the needle for anyone who cares about Seidl’s work, myself included; as a longtime fan of his films, which definitely fall into the “beautiful compositions and ugly interactions” category, I haven’t ever felt particularly confused about the potential means by which his effects—which often involve nonprofessional performers in embarrassing or outright degrading situations—might have been achieved.

WICKED GAMES begins with an echt-Seidl image: nursing home residents sitting in a neat row, their walkers in front, singing an optimistic song (“Such a day as this should never come to an end”) that underlines the grimness of aging in a composition that’s much more beautiful than is intuitive for either the material or setting. This is Seidl’s most painterly-looking work since the Paradise trilogy, a relief and surprise after the functional-bordering-on-shoddy-looking interim documentaries Safari and In The Basement. For a story, WICKED GAMES offers the equally-but-differently demoralizing sibling sagas of washed-up singer Richie Bravo (Michael Thomas) and secret pedophile Ewald (Georg Friedrich). Their contrasting homes—Richie’s in an offseason Italian seaside resort, Ewald’s in a wintry Romanian factory town—allow Seidl to recapitulate the western/Eastern Europe divide of Import/Export while finding exploitation, ignorance, misery and abject alcoholic behavior everywhere as usual.

At its best, Seidl’s worldview is pitiless, blackly funny, deterministic and extremely compelling, feinting the unaverted-gaze social realism of someone like Ken Loach while offering something much closer to the precision of Roy Andersson staged in the real world. He’s never found a space he couldn’t transform into a diorama, and the color graphic matches linking one sibling’s sequence to another are elaborate and beautifully realized, like one from the bright yellow light of a casino’s machines where Ewald kills time to the duller yellow of a poster (of himself) in Richie’s kitchen and the similarly stained glass in his bathroom. Once you’ve seen a dozen of these meticulously worked out transitions, it’s impossible to imagine seeing the films decoupled as stand-alone objects.

Still, I kind of wish I had, because at 203 minutes WICKED GAMES feels punishingly long, primarily thanks to Richie’s endless songs; three I could do, but there are well over half-a-dozen, and no matter how much the location or audience shifts, or how the charge of the schlagers changes in relation to Richie’s increasing desperation, the joke is still basically like watching SNL beat a character into the ground. Many of these tunes are also overtly racist; I assumed they were old German-language specimens I didn’t know, but it turns out a good number were written specifically for this—are there really not enough examples of the real thing that new racist ephemera needed to be created? Ewald’s segment is stronger, as he leaves his wife and opens up a “judo gym,” inviting neighborhood children to train for free.

The siblings’ father Ekkehart is played in bridging segments by the late Hans-Michael Rehberg in his last part, which required him to embed himself in a nursing home for weeks before shooting began amongst seniors with a dubious ability to give informed consent to being filmed. In his senility, Ekkehart reverts to Nazi salutes and songs; given Seidl’s track record, it would have been more surprising if this very senior citizen didn’t do something fascist, and this pays off when his giving a salute draws a responding one from one of the real nursing home patients. In the Q&A, Seidl explained that she didn’t know she was being shot for a film—a problematic example of using falsehood to draw out some kind of truth. This reminded me of the flap at the time over how it was possible to ethically shoot dementia patients for Import/Export and the obvious if unpleasant answer: it’s not actually possible, but the results might be justifiable anyway. For an hour, I was enjoying Seidl’s compositional precision and bilious sense of humor at its peak; after a while, I was just counting down to the end. But, length and all, this was a specific kind of experience festivals are built to (hopefully) provide: a once-revered, now-waning auteur presenting an object that doesn’t make market sense to a self-selecting auditorium of fans, and I was glad to be there for it.

Among my peers, the consensus favorite Tiger feature was Philip Sotnychenko’s FIPRESCI Prize winner, La Palisiada. This is an extremely cinephilic work in several senses, particularly how it deliberately withholds narrative information to extend the fundamental mystery of what it’s about; normal viewers, as they say, want to know what ride they’re on. That this is a Ukrainian movie with a Spanish title is a clue to how successfully it conceals its intentions; that title is a transcription of the Ukrainian pronunciation of “lapalissade”—a term that, according to Sotnychenko, means “an obvious reiteration of a fact that is already clear,” and thus a very dry joke in serving as a label for this very unclear film.

Palisiada begins with a 15-minute-ish prologue set in the present, shot on standard contemporary digital cameras, but its 1996-set remaining narrative is captured with period-appropriate camcorders; it takes, by my count, 45 minutes for it to become clear what’s going on within this main section, and an hour before it becomes clear how it relates to the opening and through which character. I may have been slow on the uptake and missed earlier reveals of either (I honestly didn’t grasp the start-to-finish narrative until I read a colleague’s review), but I’m reasonably sure the obfuscatory idea remains the same. While the opening depicts life among Ukraine’s young artist, the 1996 narrative follows a police investigation into the shooting of an officer. Most of this part, but apparently not all (to an indeterminable extent), is shot by an officer documenting the process, and the questionable neutrality of the unseen cameraman’s POV (including occasional off-task strivings for artful compositions) add another strata of complexity to a film that messes with viewers in unpredictable ways that have nothing to do with the plot. (At one point, music from an offscreen origin starts cutting out just like a malfunctioning DCP before the shot cuts to a kid repeatedly plugging and unplugging wires from a speaker, an excellent and very specific joke of misdirection.) After reading several interviews with Sotnychenko, the macro-picture is clearer, while his specifics remain commendably obscure.

Conversely, that the makers of La empresa are completely transparent throughout regarding their motivations, process, disappointments and failures is the nonfiction feature’s biggest asset. A voiceover narrates the experience of director André Siegers and his German documentary crew after a project about a veteran opening a business in Las Vegas fell apart. Unsure what to do, they started shooting B-roll of the city’s outskirts and landed on a Mexican day laborer who suggested they check out his hometown of El Alberto—site of the “Caminata Nocturna,” which allows tourists to pay for a simulated illegal border crossing, complete with screaming police and treks through pipeline sewage.

This kind of EPCOT variation on poverty tourism has obvious morbid cinematic appeal—and, the Germans learn, has already been the subject of documentaries made by crews from America, Canada, Australia and Japan. Unsure what fresh perspective they can discover, the filmmakers nonetheless pay the village 8,000 Euros to shoot for 30 days (seems like a bargain?)—but, by the end, they’re not sure they’ve found anything new, and that conclusion didn’t seem like false modesty to me. As a case study of the current doc boom and competition to churn out competing content around the same few flashpoints, La empresa is right on schedule, but its academy-ratio compositions of village life and lackluster interactions with locals rarely find anything truly unexpected or memorable. (The exception is a building in town that, with the production funds from a telenovela, was constructed to include a clock tower that plays Andrea Bocelli and Sarah Brightman’s saccharine staple “Time to Say Goodbye” every hour.) At the end, per their agreement with the town, the filmmakers leave behind a drive with the project’s raw footage—in color, not the drained-out fake black-and-white this is in, another contemporary trend I wish would stop.

Péter Lichter’s The Mysterious Affair at Styles condenses Agatha Christie’s first novel—which also introduced Hercule Poirot—to just over an hour. Bence Kránicz’s screenplay eliminates the voice of its narrator, Captain Hastings—the Dr. Watson to Poirot’s Holmes, a character Christie eventually got tired of and largely eliminated. Instead, the narrator is Poirot himself, giving a very long version of the detective’s signature drawing-room closing speeches, which run through the case with a TV recapper’s thoroughness before revealing the murderer. Opening shots over a lightbed of film-strips showing Albert Finney as Poirot in Murder on the Orient Express give way to an old desktop’s opening string of commands. That lightbed is a recurring visual palate cleanser between chapters pairing the narration with a variety of film and computer games, those images often three or four layered side by side or on top of each other in variably divided splitscreens.

Theoretically, there’s the potential for total overload, especially with the additional layer of subtitles; in practice, the images have such an obvious and literal relation to the plot that it’s easy to keep up. Lichter’s selections from over 100 films are unafraid to use extremely familiar staples of “magic of the movies” montages (Harold Lloyd hanging from clock hands etc.) but also draws upon many deep cuts, as well as PC detective games and architectural layout programs reminiscent of the diagrams of locked rooms offered at the beginning of many Christie novels. This visual bricolage is only mildly engaging but does help create a thought experiment: is the mere outline of a Christie novel still compelling on its own? The answer: pretty much! If Lichter had adapted literally anyone else’s work, even a close peer like Dorothy L. Sayers, I wouldn’t have cared, but this taps into affection for Christie’s work and finds a new way to reformulate its appeal.

The winner of the Tiger Shorts program, Manuel Muñoz Rivas’s worthy Aqueronte, initially presents as a formalist exercise undertaken within the verité framework of a cross-section of passengers being transported on a ferry. As characters deliver dialogue outlining sometimes melodramatic predicaments (e.g. one is about to give up on their cancer treatments), it becomes more obvious that the film must be scripted. Rivas uses the unwieldy way space is occupied by cars on the ferry to his advantage, carving up the limited area from different angles and vantage points around a multitude of obstructions. It eventually becomes clear that this ferry voyage is not just broadly metaphorical but specifically about journeying to death; the dawning realization of this bold conception, and the mundane setting within which it’s executed, is reminiscent of After Life. This is in some respects prototypical “slow cinema,” but its visual language is unique and the metaphorical thrust more ambitious than most.

Another Ammodo short, André Gil Mata’s Pátio do Carrasco, is much more overtly derivative in its relationship to slow cinema, unfolding in overtly artificial sets that can be accurately described as combining Pedro Costa’s chiaroscuro with the spotlight splashes and unattributed industrial rumbling ambience of David Lynch. There are four segments to this fractured story, whose narrative obfuscations are eventually entirely clarified (to my surprise); the second (along with the interior apartment sets of the film as a whole) must be modeled on the scene in Satantango where the village doctor sits and pounds on his typewriter before heading out to get more palinka. Here, the drink of choice is a whiskey bottle but the set-up’s the same, except instead of an obese physician we get a disabled dwarf, a move designed to seemingly troll people whose stereotypes of pretentious arthouse films are derived from leftover ’70s SCTV tropes. I love that people are still making work like this, and the very-filmic darkness of Mata’s slow-moving 16mm images is seductive, but this is also five seconds away from being an audition reel to direct the next remake of The Grudge.

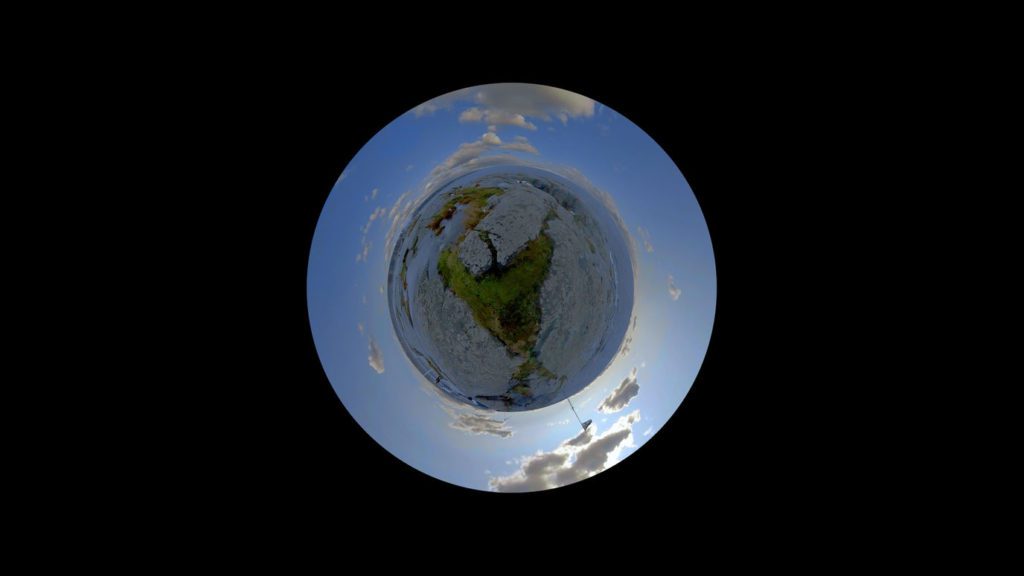

In Mateo Vega’s Center, Ring, Mall a series of seductive dollies into malls, overdeveloped cityscapes, underpopulated residential buildings and other hallmarks of the hypercapitalist present unfold against a chorus of multilingual voices reading out what seems like a pastiche of contemporary ruminations from left-leaning publications (“the mall is a ruin full of futures”), suggesting that the anti-capitalist poetry of parking lots is itself a well-codified, recuperable genre by now. But it’s not pastiche, it’s collage: The end credits list the recent canon the narration uses (a Venkatesh Rao tweet, inevitably an excerpt from Mark Fisher), thereby acting as a handy anthology of critique-becoming-cliche, though the intentionality of that gesture is unclear. And finally (phew!), commendations for two shorts that use different spatial distortions to productive ends. Hanna Hovitie’s Square the Circle has a lukewarm, quasi-poetic voiceover that feels very stock; the visuals however, presumably outputs from 360 cameras flattened into two-dimensional images, leverage the technology in very cool ways. Zooms back, which seem to come from putting a 360 on a drone, make the outdoors appeal like a giant eye with a rapidly dilating pupil, while the dazzling finale has one circle grow out of another in impossible ways, dimension jumping from circle to circle. Meanwhile, Croatian director Boris Poljak’s Horror Vacui continues in the mode he used in his previous short, They Are Coming and Going, and which I gather characterizes all six of the DP’s shorts as a director to date—filming everything from a distance with a super-long-lens (I doubt he owns one under 70mm). The resulting distortions mean that in the first shot, a huge naval carrier seen from the beach seems to be cleanly floating above the waves in a pixelated, Seurat-esque haze. Poljak doesn’t always use long lenses for distortions; a subsequent shot of the destroyer, now seen from the side passing in its enormous entirety, is a slow cinema for-scale corrective to Top Gun. The subject is militarized society but the real attraction are the telephoto views; Poljak is 64 and seems to be able to make a living without ever having to attempt a feature, which seems like an enviable way to exist.