Back to selection

Back to selection

“The ‘Micro-Budget Apocalypse Now“: Gary Huggins On His “Cursed” Debut, Kick Me

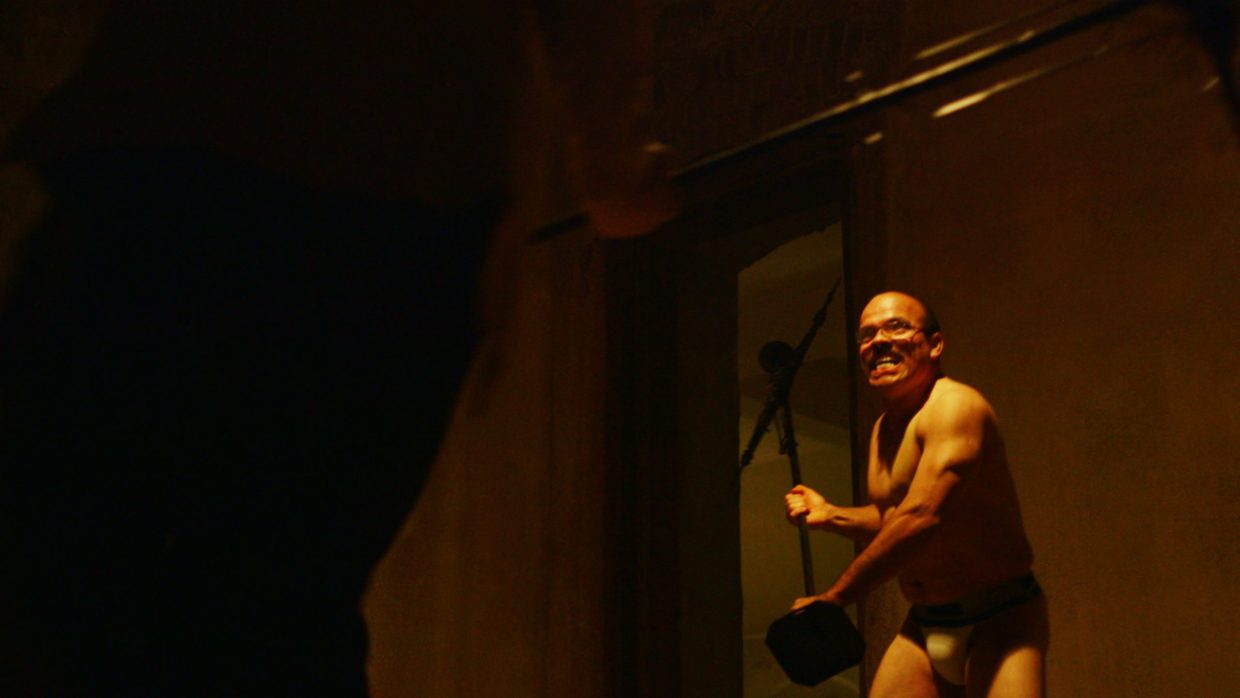

Kick Me

Kick Me A self-described “knock-knock joke ten years in the making,” Gary Huggins’ debut feature Kick Me has to be seen to be believed. The film ostensibly tells the story of a high school guidance counselor who goes into Kansas City, Kansas one night to buy a pet bunny and meet with a delinquent student before attending his daughter’s choral concert. But nothing — and I mean nothing — goes as planned. What unfolds instead is an (often funny) nightmare freakshow featuring three-legged dogs, maniacal Winnebago-driving swingers, geriatric drug dealers, abandoned shopping malls and jenkem huffers that makes Scorsese’s After Hours seem like a garden party.

Shot in 2012, Kick Me was selected for the IFP (now The Gotham) Narrative Lab in 2013. I was attending the Lab with my film Something, Anything and, though our movies were radically different, I became friendly with Huggins and his co-writer Betsy Gran. Like most of the films at the Lab, Kick Me was incomplete when Huggins previewed it for everyone, but its surreal, violent, absurd, and hilarious vision of Kansas City was already fully formed. Huggins’ voice — a mix of B-movie violence, Mad magazine satire, and his regionalist’s knowledge and love for his hometown “KCK” — was bold and unmistakable. I fully expected Kick Me to be a remarkable debut film.

But months passed after the Lab and there was no word of Kick Me being completed. Then years passed. I wondered how Gary was doing, and what was happening with Kick Me, so I would check in occasionally. Sometimes it sounded like he was tinkering on the film. Other times, we didn’t talk about it.

Now, ten years later — after a production that has its own echoes of its protagonist’s absurdly nightmarish journey — the film is complete and, following a December premiere at San Francisco’s Hole in the Head film festival, is beginning its life on the festival circuit. Though it’s early in the year, it’s not hyperbole to suggest that Kick Me will be one of the most singular debut films of 2023 — or 2013. Kick Me is a cult film waiting to be discovered by its cult.

I spent an afternoon on Zoom talking with Huggins about midnight movies, the mysteries of Kansas City, Kansas, and Kick Me’s journey, which is as unique as the film itself.

trailer: KICK ME from G. Huggins on Vimeo.

Filmmaker: Let’s start here: One of the things that makes Kick Me so singular is its regional character. If the movie had been set in New York or L.A. I wouldn’t have cared half as much about it. I might have even been turned off by it. I’ve never been to Kansas City, Kansas, but your vision of it is like a depraved, surreal nightmare. If I was going to liken it to something, I’m not sure it’d even be to a film – I might liken it to something like paintings by Peter Bruegel or Hieronymous Bosch. The film is a crazy mosaic of humanity, a city of feral three-legged dogs and maniacal swingers driving Winnebagos, almost hillbilly-like gangsters… So, tell me about your relationship to Kansas City. Have you always lived there?

Huggins: I’m from there, went to school there, and then worked for a long time at a public library in KCK’s inner city. It’s like every community that got choked by malls or Walmart, and used to be really thriving. In Kick Me there’s a scene in an abandoned mall — that’s the same mall that killed off KCK’s downtown, and now it’s dead too. But KCK is still a really vibrant community, and it’s a community of immigrants, and families, and also some people who are struggling.

When I worked in the library I made a lot of relationships with people in the community because I was the guy ordering the videos. I took requests, so I started developing friendships with the patrons, talking about movies, identifying a film they’d seen 20 years ago from a vague description and then ordering it for them. That was great. And I got to know not just the city, I got a much broader sense of who lived in that city, and what their lives were like, and what they were like.

Occasionally I ordered movies that had wild content hidden under tame box art, like Maîtresse, or Soul Vengeance, (aka Welcome Home, Brother Charles). One day, two older African American ladies — over 70, in hats, very proper — they’re returning a video, Soul Vengeance. One of the women hands me the video. She’s seen it, and she says, “I need to talk to you about this movie.” And I think, “Uh-oh, I’m busted.” Then she says, “My friend wants to rent it.” She brought in her friend who got a library card just so she could get this movie. And so it was like, “I love this audience. I love this community. I love everyone here.” These folks recommend Soul Vengeance to their friends.

Filmmaker: So, that idea of giving the people at the library what they want — I don’t want to draw this line if it’s not there – but was that an inspiration? Like, “Oh, I want to make a movie that the folks at the library would like?”

Huggins: I decided a long time ago that I wanted to be a regionalist and make movies set here, and with people set here, and stories set here. It’s just so irksome to see the laziness with which New York or L. A. become the focus of humanity. A lot of it is as regional as anything made in Duluth, you know? I wanted to try to elevate KCK and its people and mythologize them in the way that others do about New York or LA. That was kind of my motivation.

Filmmaker: When did you start to decide you wanted to be a filmmaker?

Huggins: I always really wanted to make movies, but I didn’t have the money to shoot independently and I couldn’t see myself moving to L.A. or New York and pushing my way into the business. So I was writing screenplays and making imaginary movies, and assuming that I would never get money or the attention to get them made. And then, when the first camera that shot 24P came out —

Filmmaker: The DVX 100?

Huggins: Yeah, that one. Everyone who ever wanted to make a movie and never thought they could afford to jumped onto it and started shooting stuff. I started trying to make stuff and things kept crapping out. Finally, in 2005 I made my first short, with Santiago [Vasquez], who’s in Kick Me, and that’s the one that went to Sundance. And then I just kept going from there.

Filmmaker: The first short that you finished got into Sundance?

Huggins: Yeah.

Filmmaker: That’s pretty awesome.

Huggins: Yeah, it was a good deal. It got into Sundance, South by [Southwest] and Clermont-Ferrand. [And I was named one of] Filmmaker’s 25 New Faces. And then Strand bought it. It had a pretty good run for a short.

But [the success] made me feel like I hadn’t earned it. Like, I didn’t shoot [the film] in a traditional way, and I just kind of figured it out as I was going along, and so I thought I’d fucked up weirdly. I thought, “I may have fooled everybody into thinking I’m a filmmaker.” So I got really nervous, and thought I maybe should go to film school.

So I tried. I enrolled in film school in Portland, and got there and then after a day was like, “What the fuck am I doing? This is ridiculous. I need to just make movies, however I make them. They seem to come out okay.”

Filmmaker: How many shorts did you make before Kick Me?

Huggins: I made three shorts. And then started Kick Me. In between each short [I completed] was a short that failed colossally. The first [of the failed shorts], I was going to make this really big-scale thing that was all in real time and one location with dozens of people and we had animals and people and vehicles, and it was a one-shot thing that was going through these ruins, and then it started to rain… and the rain turned into a Biblical deluge, and it swept everyone and everything away. I’m not kidding. Mud and rain and water just swept things away, and that was the end of that project. And the next failed short was another big-scale thing that just imploded terribly.

So it was a weird pattern. There was one that was good, and then there was one that was cursed.

Following that pattern, Kick Me is a cursed film. And it was cursed — completely cursed. And I think if it has any weird residual power or anything, I think it’s because it’s an accursed film that wasn’t supposed to be born. It’s an abortion. It’s a living abortion, and it has retained some kind of weird power from the oblivion where it was supposed to reside.

Filmmaker: Or maybe you’ve transcended the pattern? Maybe you’ve broken the cycle. Maybe it’s supposed to be a cursed film, and you overcame it.

Huggins: Let’s hope so.

Filmmaker: You started Kick Me in 2011. What was the inspiration for making this film, if you can even remember that far back?

Huggins: The third short I made was really depressing. Fun to make, but terribly depressing as a short. So I wanted to make something fun to watch.

And I thought it would be possible to make something that we could shoot really fast and maybe even edit while we were shooting. I knew I wanted to make something with Santiago, who was in my first short. He’s such a crazy, volatile personality. And I wanted to make something that would span the city, and show a panorama of all the people and everything. That’s what led to the idea of something that would involve him running across town in a jock.

Filmmaker: What was the writing process like?

Huggins: My co-writer Betsy Gran was living in San Francisco, I would go out there, and we would work on it, then I’d go away and work on it some on my own.

Filmmaker: The cast of characters in this movie is remarkable. And that includes the animals — like the pack of three-legged dogs. Were the characters inspired by things you’ve seen?

Huggins: Some of that came from Betsy and Santiago. Santiago was, for many years, a beat cop in KCK. And he also worked with the Narcotics division, undercover, and worked with the D.E.A.

When we were shooting the first short out on the street we ran into a pack of three-legged dogs, and Santiago went into a rap about the legendary three-legged dogs of KCK. I thought he was kidding, but then we ran into more. That had to go in.

Filmmaker: What about the — what’s the stuff that the guy hangs from the trees?

Huggins: Oh, the jenkem! That’s something that Betsy saw. She would go jogging in KCK, and on the way there notice plastic bags that were bulbous and bloated hanging from the trees. And finally someone told her what that was, which is jenkem. People who were homeless and living under those trees were shitting and pissing in the bags. Then they’d hang them and let them ferment, and then huff. It’s all the rage now but back then no one was doing it. Big party drug.

Filmmaker: Wow. Let’s talk about raising the money. You did a Kickstarter, right?

Huggins: Yeah. We worked on the Kickstarter campaign for like six months. A young woman named Leone Reeves came on board as an assistant during the campaign, she was super great and really instrumental to that and eventually became a producer on the film.

We turned the Kickstarter into this crazy narrative where Santiago had been kidnapped by the bad guys from Kick Me and they were gonna kill him unless we raised $70,000. Our Kickstarter videos were the hostage tapes bleeding Santiago for money. We worked super hard on that stuff. In the end, we actually raised $70,000. So that was the basis of the film’s budget.

Filmmaker: From my own experience, I know that when you make a movie for that little you have a small crew and you’re doing a lot of stuff yourself. What did the production look like?

Huggins: It was a tough shoot. Chaotic. I’m responsible, of course, because I made it, but there was a lot going on.

Filming almost the whole thing overnight made everyone crazy. Santiago found out just a week before shooting that he was going to have to do intensive physical training for work. All day. And our film was a night shoot. Santiago was like, “No, no, I’ll be fine.” But he was…overtaxed. So there was that element, the lead actor a little bit out of his mind because he wasn’t getting any sleep. In the end, though, it was great for his performance, he had a lot of crazy to tap into.

But that was nothing compared to what really fucked us.

Filmmaker: Which was…?

[Author’s note: When asked to elaborate, Huggins proceeds to tell an off-the-record 20-minute narrative about an uncredited producer’s misrepresentation and malfeasance that was incredibly convincing and deeply disturbing.]

Huggins: …So when I reached out to the crew this producer had supposedly lined up, none of them had even heard of the project and none of them were available. And we were just weeks away from shooting.

The only DP who was available had shot mostly gameshows and telenovelas. We went to the church where the end of the film is set. It was dark, and I was fine with that — I wanted things to fall into shadow. And the guy says, “Shadow!? I don’t want people to think I’m not doing my job!” I tried to explain, “No, I want things to fall into shadow, you know, like film noir.” And he said, this is an exact quote, “Oh, I see what you’re trying to do. You’re trying to make one of those subcultural movies. You know, a Dharma movie.” I said, “Dharma?” I’m thinking Jack Kerouac, or Dharma and Greg, and he said, “You know, Dharma 95!” At that moment I realized, “I am so completely fucked.” He lasted a week. Michael WIlson, who replaced him, did an incredible job, but our schedule never recovered.

[Huggins then goes on to tell another off-the-record story, which echoes a situation in Herzog’s My Best Fiend.]

Filmmaker: When was this all happening? When were you filming?

Huggins: The bulk of it was June of 2012. Then the next year we shot a couple more weeks and then in dribs and drabs for several years after that.

I can tell you 100 stories that are all variations on these. And worse things happened too. “The micro-budget Apocalypse Now,” is what someone on the crew called it, when the shoot was finally over.

It was pretty traumatic. I felt like I had really bad PTSD when we were done. As did others. It was so so terrible and crazy.

Filmmaker: Despite what Coppola might say about making Apocalypse Now – obviously, making a movie isn’t war, it’s not real battle. But when you care about something so much, and when you invest so much time and effort and soul and money into it… and then the experience is so brutal, when the experience is so far from what you’d hoped…It is devastating.

In 2013, we met when our projects were selected for the IFP Narrative Lab. Can you talk a little bit just about what that was like after everything you’d been through with the shoot? I guess you hadn’t even finished shooting, but with everything you’d been through already…

Huggins: Getting into the IFP Narrative Lab was the first good thing that happened to Kick Me. I probably would have abandoned it if not for the Lab. It was clear that there were gaps in the film, things we didn’t get to because of that first week of filming and other chaos, and I couldn’t tell if the thing was worth finishing. The IFP Lab convinced me it was.

Filmmaker: Now here we are in 2023, and the film recently had its world premiere — ten years later. It’s out in the world.

Though it’s rarely discussed (and usually in hushed tones when it is), as many of Filmmaker’s readers know, there are so many stories of people abandoning their debut features. A few of these folks go on to make another movie, and even become successful filmmakers. But others never return to filmmaking. Did you think of abandoning it? How would you describe those ten years?

Huggins: I abandoned it many times, either because I was broke and had to stop and make money or because I couldn’t see a way forward. I was lucky in that I had a lead who continued to believe in the project and was local (Santiago), and a friend with a camera (Todd Norris) who was willing to keep going to dismal parts of town after dark to shoot an insert of Santiago’s feet, or whatever.

Giving up was tempting. It would’ve been so easy. When you fail big like that, people don’t throw it in your face, they just quietly stop talking about it and, you know, it becomes a shame that eventually fades away. I think I just really wanted to beat that curse. I didn’t want the curse to win.

So I just kept going. It was all self-funded. I didn’t have anybody breathing down my neck about a completion date, so I could just keep working on it and fiddling with it until it worked. I feel like I have defied the adage that you can’t polish a turd. In fact, you can. If you buff it for 10 years it turns into something shiny.

Filmmaker: Well, you thought it was a turd. Obviously, IFP didn’t think that. You couldn’t get the distance from it.

Huggins: You know, it’s not War and Peace. The movie’s like a big, gross, dirty joke in a way, and so it feels like spending 10 years telling a knock-knock joke. It’s not like I spent 10 years and came out with Stalker.

Filmmaker: Maybe. But even if it is a knock-knock joke that took 10 years to tell, nobody’s heard this one before. That’s for sure. It’s definitely poised to be a cult film. And that’s actually the final thing I wanted to ask you about.

I’m probably the last person who should be interviewing you about this stuff because I don’t I don’t watch movies from this genre too often, but the easiest way I would define Kick Me to someone that hadn’t seen it is to call it a “midnight movie.” But that term — unlike other genres — says nothing about its story or style. It just says what time you watch it, and suggests a kind of weirdness that can only happen in the dark of night. What does that phrase — “midnight movie” — mean to you?

Huggins: Yeah. You know, I think “midnight movie” is a good category for films that are damaged in some way, or for films that have emotional or mental problems. If they were people they would drift in and out of jobs and like, have trouble holding down a relationship and maybe seek treatment, you know? Those kinds of movies, there’s something wrong with them. Like Gun Crazy or, you know, [Paul Morrissey’s] Heat. They’re weird, damaged movies. But that’s okay, because there’s a lot of weird damaged people that they speak to. Not everyone, you know, is Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants-healthy.

When I was a kid and I got that Danny Peary Cult Movies book I felt like such a weird, screwed up kid. All those movies were really fascinating to me. Even though it was hard to see those movies as a kid, every chapter was something you could sink into, something that tantalized you with strange damage that you hadn’t experienced yet. But you knew it was probably around the corner.

I think the best midnight movies are like that. They’re coming from a genuine, genuinely disturbed place. And I think Kick Me had a genuinely disturbed production, and it resulted in a movie that is genuine in its depiction of awfulness.

Filmmaker: I love the idea that these movies that are broken — not “broken” like they don’t work, because Kick Me is very confident filmmaking — but that they’re not just about people or worlds that are broken, that what you’re seeing isn’t just something broken on screen. It’s in the DNA of the thing.

Huggins: Yeah, exactly. There’s something about those movies, something that attracts those of us who are interested in that kind of work because of the brokenness. Because maybe there’s even a connection with our own.

Filmmaker: “Brokenness” is a word that has religious overtones in certain circles, and I’m not sure I want to go that far — but this notion of a film embodying our deep, deep human imperfections is compelling. Kick Me shows us people that are not following or fitting into the mainstream or “polite society.” Almost everyone in their own way in this movie is on the margins. Or – like the main character – gets pushed there.

Huggins: I think Kick Me has those anti-social tendencies.

Filmmaker: But movies are never fully antisocial. Movies help us find our group, our people. One way we can find a sense of belonging or community or meaning or connection is by finding people that like the same things we do. Your film’s at the very beginning of its journey out in the world but I bet at least some of the people that will find connection with this movie — with its insane, hilarious, deeply profane vision — aren’t people that find things for themselves in the movies that often.

Huggins: I’m really proud of the film now. I think it will speak to screwed-up weirdos. Though I also think regular people will enjoy it too. It’s just fun.

Filmmaker: I think that makes it more than a knock-knock joke.

Huggins: Yeah, true.

Filmmaker: What do you think the people that came to get movies at the library would say about Kick Me?

Huggins: I think they’d love it. I think it would be right up their alley.