Back to selection

Back to selection

TORONTO: ON FESTIVAL STARTS AND THE FORCE OF NATURE THAT IS BROWNIAN MOVEMENT

It’s day four here at the Toronto Film Festival—although based on the post-midnight criteria rather than the 8-hours-of-sleep criteria, I suppose it’s technically day six. The distinctions between days, between periods of lights and darks, have a tendency to become blurry after one’s tenth—or is it the fifteenth?—festival film has come and gone.

Already an appalling quantity of fast food has been eaten, numerous cups of coffee have been gratefully slurped, and at least one trusty steno pad, blank as driven snow just moments ago, is nearly full of hieroglyphics that must have meant something when I was scribbling in the dark. Soon it will be time for another.

Most of us emerge from the screenings mulling like molasses, shifting positions and opinions every time we hear someone who sounds sure of something. In contrast, the indefatigable Joshua Rothkopf and Eric Kohn, Movieliners S. T. Van Airsdale and Stephanie Zacharek, and Chicagoans Roger Ebert and Michael Phillips manage to be succinct, funny, unpretentious, and remarkably coherent just hours after screening time. Surely they are some of the hardest-working folks around. As always, some films disappoint from the get-go while others move in smoothly to monopolize mental and emotional real estate. (You didn’t think I’d name names in the former camp, did you? Let’s leave that to the pros).

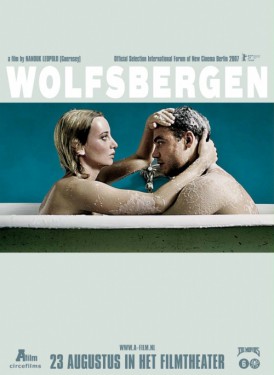

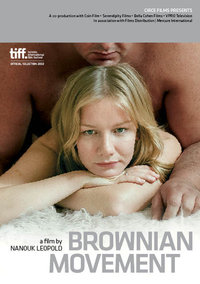

Above all, nothing I’ve seen here has struck me with anything like Nanouk Leopold’s new film, Brownian Movement. Leopold is one of the most talented and promising voices in international cinema today. A new film from her is a major event. By adding a third film to Guernsey (2005) and Wolfsbergen (2007), she has created a significant body of work. If her disturbing, uncompromising films have slipped under the critical radar, it might be in part because a feminine biorhythm underpins these devastating psychological portraits of romantic and familial relationships.

Leopold tells the story of Charlotte (Sandra Hüller in a selfless, fearless performance), a successful doctor who is compelled to undertake a series of strange sexual encounters. Her actions provoke disgust, anger, and incomprehension in those around her, including her husband, Max (Dragan Bakema) who is silently charismatic. The film is named for the scientific process that governs the seemingly random dance of individual particles, like dust floating in a sunbeam. Leopold describes the film as a study of the way in which individuals are, at base, so unique as to be unknowable to another person. In the film, she posits love as the strength to stay together even when a couple will not — cannot — ever understand each other fully.

Observe what Nanouk Leopold notices through her sense of space, architecture, and color; her precise, detailed use of sound; and her selection and direction of tiny, telling moments. They each whisper volumes about the inter- and intra-personal struggles of her characters. Even the room where Charlotte carries out her intimate affairs was lovingly designed, with every detail created around the flesh tones of its occupant. It’s almost funny that Brownian Movement is showing alongside the work of Darren Aronofsky (Black Swan) and Danny Boyle (127 Hours), two kinetic, energetic showmen who employ every camera angle and special effect in the book to produce shock and awe. Nanouk Leopold is everything they are not. Hers are not necessarily films one likes as much as films one respects, admires, and perhaps even loves.

Special thanks to Nancy van Oorschot.