Back to selection

Back to selection

TIFF 2023: Flipside, Nowhere Near

Nowhere Near

Nowhere Near Introducing his third feature, Nowhere Near, Miko Revereza said that his first, the train travelogue No Data Plan, was shot in three days and edited in about a month, fooling him into thinking every movie would be as easy. Instead, Nowhere Near took seven years and five or six entirely different cuts to compose itself. Similarly contemplating a mountain of longitudinally acquired footage, Chris Wilcha’s Flipside is assembled from work shot over nearly three decades. Their approaches and intentions are entirely different, but the two films work well together.

Wilcha is the maker of 2000’s The Target Shoots First, an immaculate workplace comedy about his mid-’90s time as a would-be rebel within the machine at Columbia House. There, he and self-consciously disaffected colleagues rationalized their salaries and occupations by creating a CD sales catalogue that simulated a halfway decent indie rock magazine. The film is near-perfect in its own way but as uncommercial as its no-sellout ethos; with Flipside, Wilcha explains what he’s been up in the decades since. Follow-up projects lost momentum and financing; eventually, he directed two seasons of This American Life and moved his family to LA for a making-of doc on Funny People. After that work entered DVD supplement purgatory, Wilcha started pursuing advertising jobs. One day, he recalls in the pervasive voiceover, when people started asking him what he did, he forced himself to stop responding “I’m a documentary filmmaker” and instead answer, in all honesty, “I direct commercials.”

Nonetheless, along the way he began a lot of never-completed docs. Much like Zia Anger’s performance My First Film, on the subject of completed-but-never-premiered features, Flipside engages directly with another widespread but rarely-publicly-discussed quality defining many in the independent film world—being a filmmaker for whom independent documentary doesn’t pay the bills but still with many Lacie hard drives full of raw material for aspirational, never-to-be-completed features. Throughout, I thought of a friend’s observation that any documentary made by someone over 40 who’s managed to complete multiple features is inherently of interest, because so few struggle on long enough to develop any kind of consistent POV to their work; Flipside is a case study in where some of those people and projects go.

Though Wilcha condenses his unrealized docs to a hyper-edited blur, they’re still interesting. The glimpses of his commercial work are likewise fascinating, like Wilcha instructing a record store owner to smirk a little wider as he flips vinyl over for an insurance commercial shoot, and the celebrity talking heads (Judd Apatow, David Milch) aren’t bad either. Even at 96 minutes, the film feels baggy (and a younger friend couldn’t handle its “Gen X whining,” which is definitely a reaction some will have), but its ramshackle organization can be an upside because of its capaciousness. Flipside takes its title and very occasional center of focus from a formative New Jersey record store; when, early on, Wilcha shows that cult TV icon Uncle Floyd is a regular crate-digger there, I flashed to my only real reference point for him, David Bowie’s “Slow Burn” from 2002’s Heathen (no contrarianism intended, one of my favorite Bowie albums). An hour later, Wilcha drops the song as performed live in concert, not cutting away for over two minutes as my heart briefly stopped at this unexpected treat. This is a movie of keen interest to both working film professionals and indexically nerdy music guys.

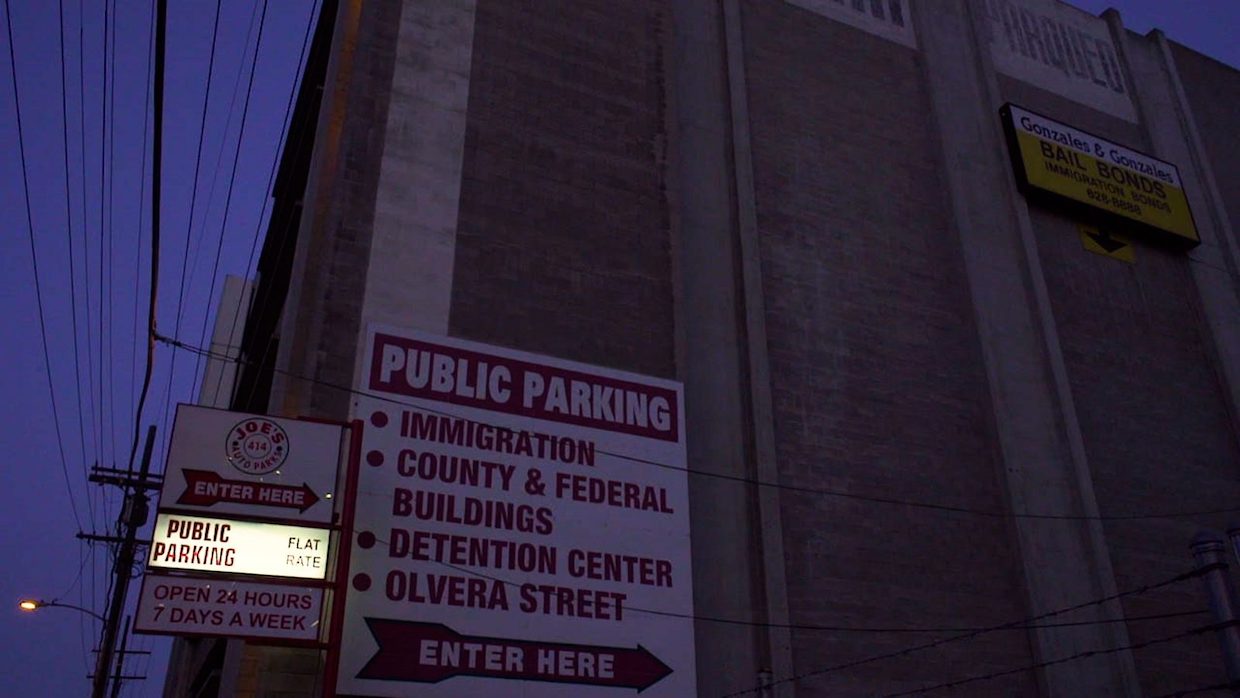

Nowhere Near is an eccentrically styled travelogue, with Revereza leveling up from the mostly onscreen-text narration of No Data Plan to a full-on, often very funny voiceover whose delivery hovers one emotive click above monotone and is more effective for it. While reflecting on familial and Filipino history, Revereza allows for unexpected detours, like a montage scored to his own free jazz clarinet skronking whose tension is amplified by the slightly unsettling images—a man air-punching towards the camera, shattered glass, a map of red states vs. blue. At one point, Revereza visits the Mall of America and finds unlikely, implicit visual kinship between the palm trees in its Nickelodeon Universe theme park and the ones in the Philippines. As a narrator, Revereza skews towards academically-inflected riffs that mostly fire, like a re-interpretation of Spirited Away as a parable about migrant children. But, wanting to get to the bottom of his parents’ story, Revereza announces “an outlier from all this whooshy experimental stuff” in the form of an interview with his mom, one he deliberately frames like a PBS talking head because this is a moment too important to be distracted from by monkeying with form. (Disagree! But I get it.)

An undocumented migrant living in the US, roughly halfway through the film Revereza returns to the Philippines with no clear path back if he wants one. The film attendantly undergoes a purposeful but nonetheless more enervating formal change, a metabolic shift in keeping with the relocation. Shooting in a church, Revereza is clever enough to call out his work that day as shaky and underexposed, then re-interpret that failure to make the footage’s technical failures theoretically valid: “It’s like the camera is possessed. We were possessed.” Then it’s off to the races to reposition that as a suitable metaphor for the effects of colonialism on the Philippines. While there, Revereza also visits the location where the real-life events dramatized in John Dahl’s The Great Raid took place; it’s a movie I haven’t thought of since its 2005 release and a useful reminder that even the most forgotten films generate someone somewhere with either a passionate fandom, completely unexpected reading or simply a rooting interest in seeing their home turf on-screen. If I found Nowhere Near‘s back half tougher going, Revereza’s development as a filmmaker, and his investment in long-form diary filmmaking as the jumping-off point for unexpected ruminations, are worth keeping an eye on.