Back to selection

Back to selection

Extra Curricular

by Holly Willis

Lessons from the AI Filmmaking Rabbit Hole: Holly Willis on Teaching During Rapid Technological Change

An AI Dreams of Dogfish

An AI Dreams of Dogfish I recently found myself sitting between three tech bros on my right and three cinephiles on my left. The film festival panel was meant to be a discussion about AI in the film industry; instead, it was an exasperating—if entertaining—demonstration of the radical gap in knowledge separating people who have some technical understanding of AI and those who don’t. There were tone-deaf proclamations about “generating content” and “optimizing workflows” on one side. And there was shouting, swearing, table-pounding, finger-pointing and (almost) tears on the other side, culminating in the announcement, “We’re very afraid!”

I get it. AI has been foisted on all of us suddenly by a handful of major tech companies in a mad, global scramble to capitalize on new tech. The data that underlie the tools for text-to-image generation were obtained without permission and are full of biases. The paradigm of image creation that eschews cameras and instead uses things like “large language models” and “latent diffusion” seems completely alienating to many filmmakers, screenwriters, actors, casting directors and a long list of other creatives who have honed their craft with real people and real light and real cameras for many, many years. Where some see exhilarating creative freedom in crafting moving images by typing sentences into Runway, others see further exploitation by studios, the decimation of careers, an ethics debacle and—well, the downfall of cinema, if not civilization, as we know it.

My panel adventure happened in early November, only a few days before the Screen Actors Guild strike ended. I witnessed this confusing swirl of AI hype and doomsday fretting previously when I launched a new undergrad class in the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California, “AI and Creativity.” Two colleagues also designed and offered AI-focused classes at USC: Ben Hansford taught “Contemporary Directing Practice” in the production division of SCA, and Gabe Kahn taught “Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Creative Work” in the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. All three of us spun these classes up in a hurry, feeling a sense of urgency to respond to the rapid changes around us and wanting to make sure our students had a space within which to think, make, critique and—eventually—help teach others. We had some support from the community created as part of USC’s new Center for Generative AI and Society, which is dedicated to a critical and reflective inquiry into AI as it relates to storytelling across cinema and journalism.

“AI and Creativity” was designed as a hybrid theory/practice course, combining readings on machine learning (what the heck is it?); discussions of the material implications of AI (devastating mineral extraction and often horrific labor conditions); visits by artists, designers, filmmakers and a lawyer; and hands-on tool experimentation moving across ChatGPT, Midjourney, DALL-E, Pika, Kaiber, Runway, HeyGen, Firefly, Photoshop and Premiere. We also explored sound through ElevenLabs, 3D character generation with Wonder Dynamics and some photogrammetry with Luma AI and NeRFs. I tried to stay one step ahead of the students, each week avidly learning how to prompt, upscale and blend images, as well as how to mix and match subjects, media forms and styles. Of course, I did not stay ahead, and the class instead became a participatory teaching space, with students showing one another how to do things.

I was better suited to exploring the broader, historical context within which AI appears, so we also talked about how an array of new technologies, not just AI, has resulted in powerful reimagining of time and space and the creation of what has for more than a decade been dubbed “post-cinema.” Film scholar Steven Shaviro describes the shift in his 2010 book Post-Cinematic Affect: “Just as the old Hollywood continuity editing system was an integral part of the Fordist mode of production, so the editing methods and formal devices of digital video and film belong directly to the computing-and-information-technology infrastructure of contemporary neoliberal finance.” In his book Discorrelated Images, scholar Shane Denson describes a new form of image, pointing to the ways in which the “crazy cameras” and visual chaos, often characteristic of virtual filmmaking techniques, dismantle traditional cinematic orderings of space and time. He writes, “At stake in the question of discorrelation is not just a reshaping of cinema, or the development of new technical imaging processes, but a transformation of subjectivity itself.” Indeed!

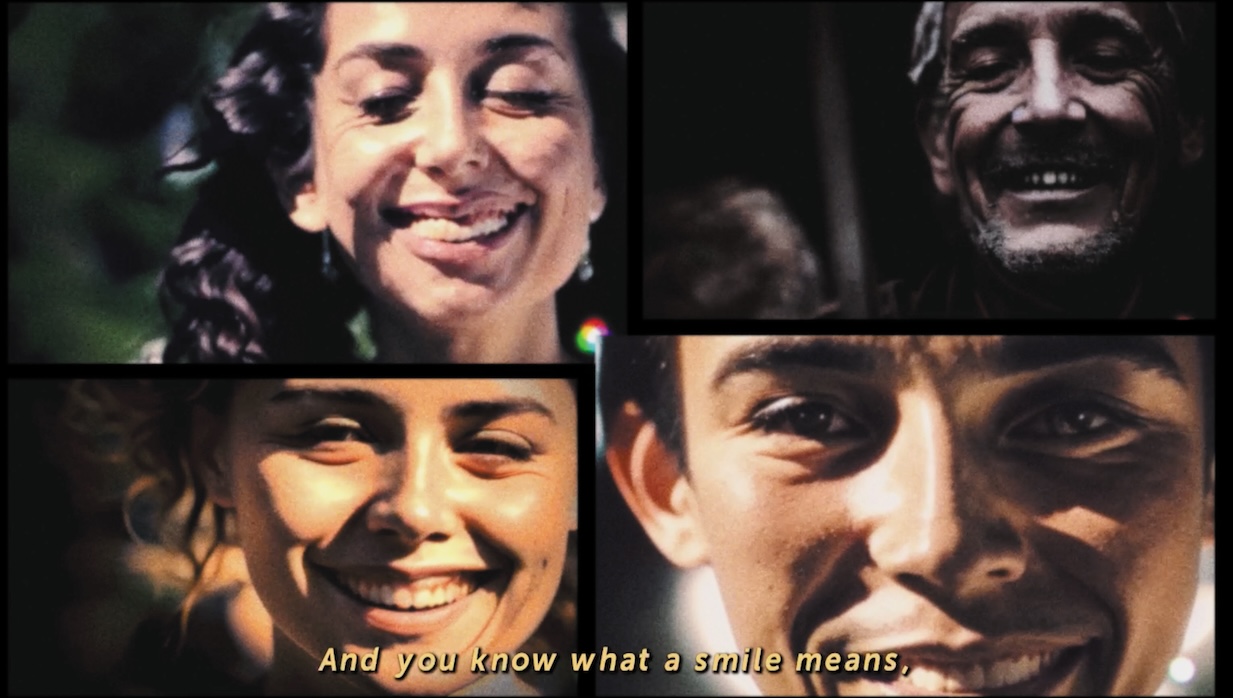

While I could cheerfully revel in heady philosophical musings all semester, my students responded more avidly to guests such as Souki Mansoor, an award-winning documentary filmmaker who stumbled into the AI filmmaking rabbit hole nine months ago and hasn’t emerged. She offered a fast-paced and exhilarating trip through her thinking, workflows, self-care strategies, tools of choice and resources. She encouraged thoughtful making, underscoring that the stories we tell at the beginning of this new era have significance in helping shape what will come next. Mansoor also showed several of her own projects, including An AI Dreams of Dogfish, created using prompts excerpted from the lines of Mary Oliver’s poem “Dogfish.” The snippets of text work well to caption the short moving image segments, creating a dreamy, associative vibe perfectly suited to the form at the moment.

Another video created by Mansoor during the recent Gen:48 Runway 48-hour short film competition hosted by Runway Studios, An AI Dreams of Beedoo, makes great use of AI’s capacities for surrealism to tell a children’s story about an octopus traveling through the cosmos. The project hops stylistically from storybook illustration to Japanese woodblock, taking full advantage of the morphing, shimmery visuals of Runway video. Mansoor also described using NeRFs—3D scenes created from 2D images—as a way of producing camera moves for a short documentary addressing trauma, noting that the practice produced “a graceful way of dealing with a tough situation.”

While peeking into someone else’s workflow is invariably exciting, I was most struck by Mansoor’s attention to our current moment with a section in her presentation titled “Let’s Talk About Feelings.” Here, she pointed to them all: feeling stressed, intimidated, hopelessly behind everyone else and so on. “Our monkey brains were not designed for this rate of change, so we can get overwhelmed,” she said. “But we can learn sustainable ways of working. Take a break!”

In addition to Mansoor, one evening we also were joined by LA-based photographer and ceramics artist Ann E. Cutting, who offered a terrific Midjourney image-generation workshop, helping us understand the nuances of prompting. She demoed Photoshop’s new AI capacities with generative fill, which lets users both expand the edges of an image and either remove or add new elements to any photograph. She also discussed the ethics of image creation using these tools and reminded students that the U.S. Copyright Office has declared that images generated through AI cannot be copyrighted because they are generated by machines. Cutting’s own Midjourney images are striking, otherworldly portraits of people in surreal habitats that hover between surrealism and fashion photography. They boast a sense of precision and beauty that can be challenging to achieve. In another series, Cutting has created images of playful birdhouses with an aesthetic reminiscent of the clean lines, palette and geometry of the Bauhaus. The images point to the potential of AI when used by skilled artists who have a sense of history and understand fundamental concepts of visual design, color and framing.

Keen to expose students to many different people in the emerging AI context, I was delighted to welcome a team from the nonprofit advocacy organization AI LA, including its president Todd Terrazas, the group’s head of design, Rachel Joy Victor, and Eric Wilker. The three recently created FBRC.ai to support AI startups. Victor presented a dazzling overview of machine learning, drawing on her background in computational neuroscience and data analysis but using plain language to walk us through the complexities of encoders, decoders and latent space. Together, the team offered an overview of the broader impact of AI, moving away from specific tools to think about AI as it relates to health, transportation, education, music and the arts more broadly. Other visitors included lawyer and Boston College professor David Olson, who talked about IP and copyright, and artist and visual arts professor at UC San Diego Memo Akten, who shared his research and experiments involving AI.

While visitors helped keep the class lively and up to date, we also read a lot. A People’s Guide to AI, by Mimi Onuoha and Mother Cyborg (Diana Nucera), reminded us that computation is all around us; we inhabit an algorithmic, surveillant culture. Kate Crawford’s The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence highlighted the fact that while AI sometimes feels like a spectral, disembodied force, AI systems are quite tangible and material, often in negative ways. Mashinka Firunts Hakopian’s essay “Ancestral” pointed us away from celebratory claims of novelty that demand new ways of knowing toward the wisdom of ancestral intelligence; Sasha Costanza-Chock’s “We Need to Design AI Systems Free of Bias and Harm” sums up a powerful orientation from the context of design that we would do well to adopt in the context of filmmaking; and Nora Khan’s “Seeing, Naming, Knowing” highlights a key issue: “Racial capitalism, weak machine learning, and algorithmic surveillance intersect to create a world that is not better seen, but less seen, less understood, more violent, and more occluded.”

If the reading often felt heavy and discouraging, the work of a long list of artists and filmmakers pointed to the powerful role of artworks that can both describe and defamiliarize AI, and indeed new media artworks have served this function for more than 20 years. Our viewing spanned the media art of Suzanne Kite, an award-winning Oglála Lakóta artist, composer and academic; artist and activist Morehshin Allahyari; and self-named digital shaman Connie Bakshi; as well as music videos and shorts by filmmakers such as Paul Trillo, Jake Oleson, Jonas Lund, Millie Mills, Joss Fong, Áron Filkey and more.

The past four months have been a heady, challenging time, and my students weathered it well. Many said they felt uncomfortable using AI at all given the significant role it played in the WGA and SAG strikes; several even admitted they were keeping their enrollment in my class a secret from their friends for that reason. Others deeply disliked the disruption of their own creative workflows and initially found working with ChatGPT, Runway and Midjourney alienating and difficult. It was not really until week 12, when their short video assignment was due, that many students began to feel more positive about their work. And the videos were extraordinary: Each around 90 seconds, they were unique to each maker, often beautiful, weird and moving. Students frequently found in the strange, morphing aesthetic a way to express something profound about personal identity, and I was very impressed with the work overall. Was it easy? Absolutely not! What we all learned was a fact expressed over and over by my colleague Ben Hansford: “You gotta do the work!” Definitely true.

And my colleagues? I asked them both to sum up their semester. Gabe Kahn said, “One of the issues about AI I think of most is, ‘When does it just make us lazy and when does it make us more creative?’ Over the past semester, I’ve gleaned that when you have actual humans working collaboratively in small groups, using multiple AI models, something truly exciting happens.”

Hansford, as always, was quite blunt: “While I love the work of Ridley Scott, he’s talking out of his ass when he says everyone can now make a film with the phone in their pocket, as though the hardest part of moviemaking is the equipment rental of a camera—and not the marshaling of an unpaid army for 20 days. But now with generative AI, if an artist is willing to adopt the format, they really can create stories as long as they want, all by themselves.”

Returning to the festival panel discussion, when the cinephiles poignantly expressed their sense of confusion and fear, my response was that of a professor: We all need foundational AI literacy! We need to understand how AI functions, how it informs and shapes much of our everyday lives and how text-to-image generation actually works. We also need big, creative imaginations to conjure practices and systems made by creatives for creatives. Filmmakers, writers, directors, actors, producers, scholars—none of us can hide behind a lack of understanding or a sense of dread. We need to step up and learn from the vast array of resources readily available, much of it created by artists, filmmakers, activists and scholars. Just imagine if the actor raging next to me, who had testified in front of Congress about the dangers of AI just a few days earlier, actually understood how machine learning functions and could, as a result, express with clarity and nuance the future he wants to see, one where he is empowered rather than exploited.