Back to selection

Back to selection

TORONTO: ON ELEPHANTS, VIOLINS AND TATTOOS: AN INTERVIEW WITH DOUGLAS GORDON

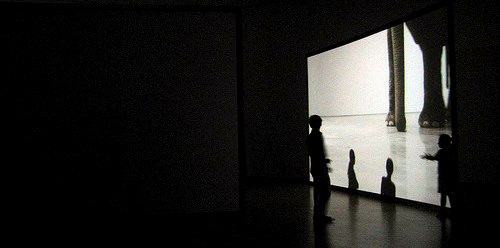

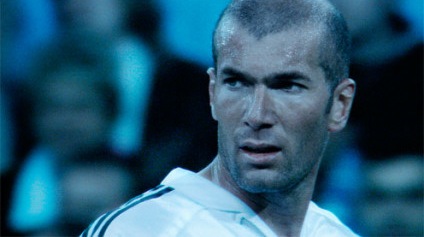

Have you ever seen an elephant lie down? This question provoked Scottish artist Douglas Gordon to create Play Dead; Real Time, a giant, startling multiple projection depicting just that. Timeline, a beautiful Gordon exhibition the Museum of Modern Art in 2007 that included the piece, was a triumph not only with art enthusiasts but with cinephiles as well, and Gordon regularly walks the line between these two worlds. In addition to his successful art career and installation pieces, he has made two feature films: Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait (2006) and a new work, k.364 A Journey by Train (2010).

Both are intimate portraits: the first of the legendary soccer player; the second of two world-class musicians, Avri Levitan and Roi Shiloach. They are a violist and a violinist, respectively; both are of Polish-Jewish extraction. In the film, Gordon follows along as they travel by train from Berlin through the town of Poznan, where a swimming pool that has replaced an old synagogue. Tracing a route their forefathers traveled under dire circumstances during the second World War, they arrive in Warsaw, where the two men lead an orchestra in a virtuoso performance of Mozart’s “Sinfonia Concertante in E Flat Major.”

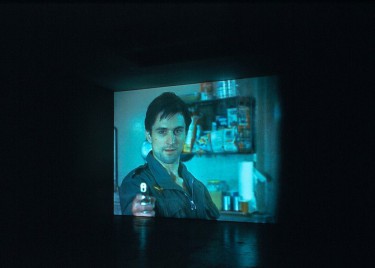

Gordon is also represented at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival by a new installation of 24 Hour Psycho, his signature piece, which is on view in the new TIFF Bell Lightbox, a towering, modern “shrine to cinema” that was just inaugurated and opened the public on Sunday. The new piece, now a two-channel work entitled 24 Hour Psycho Back and Forth and To and Fro, is part of Essential Cinema, a broad survey exhibition that includes installations by Guy Maddin, Michael Snow, and Atom Egoyan. (The exhibition has also caused controversy by naming its top 100 films; among other grievances and ironies, Life is Beautiful (1997) trumped The Sorrow and the Pity (1969); Bringing Up Baby (1938) trumped Singin’ in the Rain (1952); and Slumdog Millionaire (2008) amazingly trumped them all). In this conversation, recorded above the city in the pristine Lightbox members’ lounge, Gordon discusses his latest cinematic concoctions, shares the personal stories behind his tats, and ruminates on an Indian elephant named Minnie who lay down for the world.

LIVIA BLOOM: What was it like growing up in Glasgow?

DOUGLAS GORDON: I was born in Glasgow, but I grew up in Dumbarton, which is like the Riviera of Glasgow. (Laughs) It was a rough and tough kind of a place. But there was a fantastic library, and I grew up as a Jehovah’s Witness. So I didn’t really need stimulation from anything. Got all my stuff from the Bible.

I think I drifted away when I was about 16. In the nicest possible way, actually. My mom is still a Jehovah’s Witness, and my dad is not. He’s an engineering pattern-maker, essentially a very high-end carpenter. Let’s say this: my dad’s a carpenter and my mom’s called Mary, so I grew up with some messianic issues. When I lived in Glasgow with them, we had a very, very small family home. Like any kid, when I couldn’t sleep, I used to go to bed with my mom and dad. That’s initially where my experience of cinema happened.

BLOOM: Lying in bed with your parents as a child?

GORDON: Yes. I probably did see films that weren’t meant for a 3-year-old. I have very vivid memories of lying in bed with mom and dad, watching The Searchers (1956), or gangster films. My experience with cinema was really in bed. Which I still think is nice. I’m amazed that at a place like this [the newly opened Tiff Bell Lightbox], they don’t have a bedroom. (Laughs) I don’t want to get too nostalgic about it, but in those days, things were just broadcast at certain hours. The choice was watch it, or don’t. It was quite different from the multiple choices we have now.

My girlfriend takes the piss out of me all the time, “You don’t really watch anything made after 1960, do you?” Well, I try, but I always go back to the period of cinema I’m most attracted to. It’s probably something to do with this Roland Barthes idea that I remember reading in his book on photography [Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, 1980]. He says there’s a connection for people to a time just before they were born, when their mom and dad were just about getting it together, and then the nine months when we were gestating. It’s a very romantic idea, but I kind of subscribe to it. I love the films from the period right before my birth.

BLOOM: What brought you to your new film, k.364 A Journey by Train?

GORDON: I always think that work, which is difficult to begin with, is better later. When Zidane came out, for the producers I think it was the most disappointing exercise that they’d ever been involved in. (Laughs) I always said, “Zidane’s going to be amazing in about 15 years.” And I still think it would be. Things take time. The kind of work that I do and what gives me pleasure is taking a very long time to do something very small. But that very small thing, when you put it into wine or vinegar and marinate it, that’s where your taste comes from. A slice of lemon, when you just cut it, is that. But when you put it into a jar of tequila for nine months, it becomes something else entirely. I think with k.364, once people have seen it—if they ever see it—they’ll never listen to that piece of music again without those images.

BLOOM: What is the blue tattoo around your throat?

GORDON: It goes all the way around. It was the most painful one. I was having dinner with an Algerian friend and his wife in Paris and, describing his life and the racism he encountered after moving from Algeria, he wrote “One life, one love, one God.” It sounds a bit like a U2 song, but if you take Bono out of the equation, it’s a really beautiful statement. Under it is the only tattoo that my mom likes: it’s the name of the place I was born, Mary Hill. It also starts with her name, you see.

BLOOM: And on your wrist?

GORDON: Oh God, the wrist thing? This one is “Never” and this wrist is “More.” I’m a big Edgar Allen Poe fan. The one here [on the left wrist] was so painful. More than the other wrist. I got as far as having it outlined, and then decided to let it appear that that was as far as I’d planned to go! I couldn’t take it anymore. A really nice one is that [a tattoo of “Forever” that is lighter than Gordon’s flesh tone] which is the ghost of the other one on the other arm. This one is “Ever” “After” “All”. “Everyday” was a very romantic one. My son’s mother had the same word the opposite way on her shoulder, so that when we were old, I could put my arm around her and they would fit together.

BLOOM: Which was your first one?

GORDON: This one here, that just says, “Trust me.” I wasn’t that young when I got it; I was certainly in my twenties. In the early 1990s, when there weren’t tattoo places everywhere like there are now, I went into this place that was full of guys drinking beer and smoking. I walked in, and then walked out. Later, I called the tattoo voice and said, (high voice) “Hello, can I make an appointment to have a tattoo, please?” And they were like, “Fuck off. Just come in on a Monday morning at 9 o’clock.” It took me about three months to work up the courage to do it again. I worked hard on the typography, and it’s really small [about 4” on the left upper arm]. It’s probably disappeared—it’s a tiny, tiny tattoo. Oh, there it is. I finally went in at 9 o’clock in the morning, and met Teddy Tattoo. It was like going into a brothel or something. He said, “Have you done it before?” (High voice) “No…” “Let me see it.” He looked at my piece of paper and said, “Pft, that’s way too small.”

I was completely crushed. He turned me down. As I was walking out, this young guy came in with full Guns n’ Roses tattoos up to here. He said, “What’s up?” and I answered, “That old fucker won’t give me a tattoo.” “That’s my dad.” And he did it himself, instead.

BLOOM: Why did you pick “Trust me”–did you feel that people didn’t trust you?

GORDON: No. It was to take the piss out of my family situation because of the religion.

BLOOM: It was a reminder to you to trust yourself.

GORDON: Yes. I think that people get tattoos done in order that they can look in the mirror. It gives them an excuse, in a way.

BLOOM: How did you choose those musicians in your new film?

GORDON: They presented themselves. The viola player is the ex-husband of my girlfriend. I live in Berlin, and hang out with a lot of musicians and Jewish musicians in the classical music world. It’s kind of funny, because I used to work a lot with Chicks on Speed. So I was in a girl band that was performance art-based. It wasn’t classical. My girlfriend is a soprano, and it was an eye-opener for me to see how another art form is maintained. I played this little game in the opening titles: it says “Avri Levitan as the violinist” “Roi Shiloach as the violist.” In Venice, a few journalists asked me about this: could the film star actors instead of real musicians? Avri said, “No actor could ever hold the violin the way a real violinist could.” I love that type of peculiarity and specificity. Perhaps its something that’s lacking in my life; in any case, it’s incredible. You know, the tattoo thing is really not so different from the music thing. When you see a finger applied onto a piece of string, it’s not so different from seeing someone dig into your body.

Have you read Don Delillo’s last novel, Point Omega? The book opens in the room where 24 Hour Psycho was at MoMA. The narrative starts form the point of view of someone leaning against the wall and looking at the work. That goes on for 20 pages, and then there are only 70 pages left. Every sentence is like a film still.

BLOOM: Tell me about the elephant. Did you film only one, or more than one?

GORDON: One. I woke up one morning and I thought, “I’ve never seen an elephant lying down.” I’d seen elephants in the circus and all that shit, but I’d never seen one lying down. I made telephone calls to friends, and asked, “Have you ever seen an elephant lying down?” Everyone one said, “Nope.” So I knew I was on to something.

My gallery in New York, Gagosian Gallery, they’re really good at organizing stuff. I called them that same day and said, “Can you guys get me an elephant?” “What kind of elephant do you want?” “A male African elephant.” They called back shortly and said, “No one is going to give you a male African elephant. They’re crazy. But we can give you a female Indian elephant.” “How tall is she?” I asked. “About 14 feet.” “That’s pretty good.”

And that’s how I met Minnie, my elephant. When I was trying to organize this, the guy who owns Minnie sent me some photographs. It was like a casting. In the pictures, she had nail polish and fake eyelashes—so sad. I went, “Oh no! I just want her to be her!”

They brought her into New York at midnight, and we walked her down Tenth Avenue to the gallery. New York cab drivers have seen it all, but they were still open-mouthed. It was still fantastic. When she arrived, she had a bit of a cold, and she was sneezing like this. (Makes noise) The big gallery rolling door was there, and Minnie nuzzles against it… and fucked the door, totally, just by nuzzling against it!

BLOOM: What kind of equipment did you use?

GORDON: It was probably an Arri with a very wide lens. There was a Richard Serra sculpture in the gallery, and the elephant almost brushed against it!

BLOOM: Did you get what you were looking for in the footage?

GORDON: Yes. She lay down; stood up. Lay down; stood up. She was very sweet. What I learned from the trainer was that elephants, especially African ones, don’t like to lie down. When they’re lying down, they’re vulnerable. So African elephants sleep leaning against a tree. Indian elephants don’t have as many predators, so they can lie down, but they don’t like it.

At one point, she was lying down. She opened her legs and we all see the biggest vagina ever. Everyone on the crew was like, “This isn’t a porno!”

BLOOM: Your use of scale is often very striking.

GORDON: Life-size is good. When I started working with film and video, I wanted to hover in between the largest painting you’d ever seen and cinema. When you’re a kid, you do have the fantasy that if you penetrated the screen, you could go into The Wizard of Oz. I wanted to play with the magic. With 24 Hour Psycho, I wanted the magic, but then I wanted people to be able to walk around it, see the illusion, and still be enthralled by it.

I’ve been criticized for a lack of content and too much focus on scale. If I did a very small projection of the elephant, I think it would still be powerful. If you close your eyes, with the exception of when you dream, you only ever see an image as big as it is from here to here. (Gestures from the outside corner of one eye to the other) It’s provocative to take that into another setting. There’s something physical and sculptural about confronting something larger than your expectations. As a kid, I remember at the end of a James Bond movie running down to touch the end credits on the screen. As you get closer to what you want, it starts to evaporate.

Special thanks to David Balzer, Nancy van Oorschot, and Zeynep Yücel.