Back to selection

Back to selection

Robert M. Young, 1924-2024: A True Giant of American Independent Filmmaking

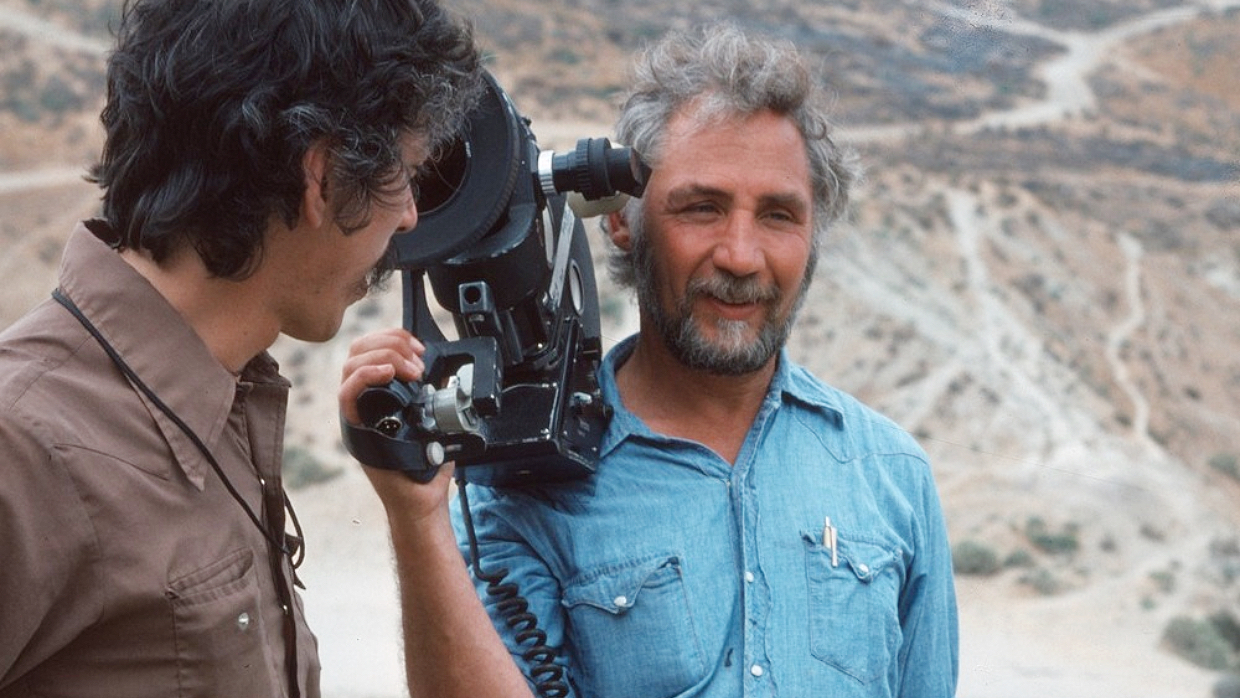

Bob Young with his Eclair NPR and Tom Hurwitz ASC on set of Alambrista!

(photo courtesy Andrew Young)

Bob Young with his Eclair NPR and Tom Hurwitz ASC on set of Alambrista!

(photo courtesy Andrew Young) Robert M. “Bob” Young, often described in the film era of the 1980s as the godfather of American independent filmmaking, has died. His son Andy, himself an award-winning filmmaker, announced Young’s death on February 7th in a Facebook post:

“He was a rebel in the industry, who made the films he dreamed of and lived the life he wanted, whether it was trekking through the Congo, swimming with sharks, or plumbing the depths of the human experience. He was 99 years old, and while the final years were sometimes tough for a guy who lived to do it all, he managed to die peacefully among family and friends. He will be so deeply missed.”

Young began his career in the 1950s, in documentary production for educational markets. He innovated underwater filming techniques and co-directed and co-shot a successful 1957 series called Secrets of the Reef. Eventually he landed at NBC News, directing and shooting. He was director, writer, and associate producer of Sit-In, an hour-long installment of the primetime documentary series NBC White Paper, which aired in December 1960. Narrated by NBC News anchor Chet Huntley, it profiled the surging sit-in movement in the South. It won a Peabody.

In 1961 Young and filmmaker Michael Roemer turned their camera on a decrepit slum in Palermo, Sicily, called Cortile Cascino, embracing then-new cinéma vérité techniques for the first time. NBC deemed Cortile Cascino too grim and declined to broadcast it, pulling it two days before scheduled broadcast. Young and NBC parted ways—he was fired—launching him into an independent filmmaking career. (Thirty years later, the filmmaking team of Young’s son, Andy, and his wife, Susan Todd, returned to Cortile Cascino to track down individuals profiled in the original film. Their 1993 film, Children of Fate: Life and Death in a Sicilian Family, won the 1993 Sundance Grand Jury Prize for Documentary and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.)

Young and Roemer reteamed on two acclaimed independent classics directed by Roemer, Nothing But a Man (1964) and The Plot Against Harry (1971, released 1989). Young was co-writer, producer, and cinematographer of the first, producer and cinematographer of the second. Nothing But a Man featured Black leads—Ivan Dixon, Abbey Lincoln, Yaphet Kotto—and pioneered the use of radio hit singles as soundtrack, a technique later associated with Martin Scorcese, resulting in Motown Record’s first soundtrack album.

Young was producer and director of the riveting Short Eyes (1977), a scathing prison drama based on the award-winning Broadway play by Puerto Rican playwright Miguel Piñero. Not only were Freddy Fender and Curtis Mayfield featured in the cast, but Mayfield wrote the score and released what is perhaps his next-best soundtrack album after “Super Fly.” Both soundtracks are now classics of 1970s R&B.

While each of these films was shot in 35mm, Young’s previous documentary background had left him open to the possibility of applying smaller, more nimble equipment to production of theatrical dramas. His next film, Alambrista! (1977), which he wrote, directed, and co-DP’d with Tom Hurwitz, was shot in 16mm and blown up to 35mm for release. It won Camera d’Or at Cannes for best first film.

It didn’t hurt that Young’s little brother was Irwin Young who ran New York’s DuArt Film Laboratories, founded in 1922 by their father, Al, a former film editor. Irwin had recently acquired an optical printer (functionally equivalent to an enlarger in stills) for 35mm blow-ups and hired a young hotshot technical director to build up DuArt’s optical printing operation. (That would be me. Alambrista! was the first feature blow-up I did for DuArt.)

In adapting the lab for 35mm blow-ups, Irwin was directly influenced by the filmmaking needs of his brother. Bob had grown increasingly intrigued by Super 16. No 16mm film camera had ever required both sets of perforations. In the late 1960s, a Swedish cinematographer, Rune Ericson, had begun to ask: Why not eliminate one row of perfs and extend the image all the way to the edge, resulting in a wide aspect ratio for blow-up to 35mm?

To achieve a 1.85 theatrical aspect ratio for 35mm blow-up, Young had had to significantly crop the top and bottom of the original 1.33 frame of Alambrista! With Super 16, this top-bottom crop would have been unnecessary, and there would be an extra 2mm of image width, totaling almost 60% more image area for blow-up. This would mean less enlargement by the optical printer, translating into better sharpness and finer grain in the 35mm image. Inasmuch as Super 16 negative cost the same as standard 16mm, something for nothing. Also influenced by this new way of thinking about 16mm was Jean-Pierre Beauviala, founder-inventor from the French camera manufacturer Aaton. His initial 1972 prototype Aaton was Super 16 only.

After finishing production on Alambrista!, Bob shot tests in Super 16 using his Eclair NPR, which he had modified by milling the aperture to the wider dimension of Super 16. DuArt made test 35mm blow-ups, and the results were so impressive that DuArt, in order to further vet the format, acquired a Super 16 Aaton, a set of 16mm Zeiss Super Speeds, and a Cooke Varo-Kinetal 10.4-52mm Super 16mm zoom (first one imported to the U.S.). To nix the possibility of damaging the extended image area, DuArt modifed developing machines, printers, optical wet-gates, synchronizers, frame-count cueing stations, cleaning machines, telecines, projectors — every device that touched or handled the larger Super 16 image.

Using DuArt’s Super 16 camera and lenses, Bob shot his next theatrical feature, The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez (1982), which became DuArt’s first 35mm blow-up from Super 16. In the process, DuArt single-handedly opened the U.S. market to Super 16 production, not only ensuring the viability of the new format but becoming, throughout the 1980s, the premiere lab for 35mm blow-ups in the U.S.

Meanwhile, over in Grenoble, France, Jean-Luc Godard had challenged Aaton’s Beauviala to create a handheld 35mm camera as compact as a Super 8 camera, called Aaton 8-35 at the outset. To Bob Young, who liked to operate, this was pure catnip. DuArt placed a substantial deposit on one of the first 8-35 prototypes, which was later replaced by a production model called the Aaton 35. It was this lightweight 35mm camera that captured much of Triumph of the Spirit (1989), the first drama about Auschwitz-Birkenau shot on the actual grounds of the camps since the war’s aftermath. The ghastly location no doubt inspired Willem Dafoe to give inarguably one of his finest performances, as a Greek Jew whose boxing skills are sadistically exploited as entertainment for camp staff. Young’s DP was Curtis Clark, who several years previously had shot The Draughtman’s Contract in Super 16 for Peter Greenaway.

(N.B. There is but one precedent to Triumph of the Spirit in terms of location, and it’s worth mentioning: The Last Stage (1948), directed and co-written by Wanda Jakubowska, a camp survivor. Although a drama, The Last Stage is hauntingly documentary-like, as the camp is still utterly intact, electrified fences and rutted muddy roads included. Extras include locals from Oświęcim, the Red Army, even German prisoners of war. An overlooked classic of world cinema, by a woman writer-director no less, Young would have seen and studied it.)

One of Young’s last films is one of his most extraordinary, in terms of production. Human Error (2004), which premiered at Sundance 2004 when Young was going on 80, was not a hit, but in its ambition and audacity, it trounced much else at the festival. Remember Tron from 1982? You probably don’t, unless your hair is mostly gray, but Tron, the story of a computer programmer (Jeff Bridges) who gets digitized into the software realm of a video game, was an utter breakthrough in use of CGI and computer animation to conjure the look of imaginary digital worlds. A decade later, CGI was still considered slow, expensive, out of reach for most, especially independents.

Young had a very different story to tell, based on screenwriter Richard Dresser’s Off Broadway play, “Below the Belt,” about a couple of mid-level managers co-existing at a grimy manufacturing plant in the middle of a post-industrial nowhere, bickering and conspiring against each other when not being manipulated by their supervisor. Not an obvious candidate for computer animation and wall-to-wall CGI, but Young shot the principals against greenscreen in a studio in Colorado, then spent several years building up a CGI company of young programmers and a rendering farm on the 10th floor of the DuArt building in Manhattan. This scale of computing was necessary in order to composite live action against animated CGI factory backgrounds along the entire length of the feature, for output out to 35mm. (Bear in mind, these were PCs from twenty years ago.) Hands down, the first time such a thing had been attempted as an independent production.

Most significantly, Young was known as a director actors adored. A partial list of actors he directed includes: Edward James Olmos, Ned Beatty, Willem Dafoe, Robert Loggia, Bruce Davison, John Lithgow, Blair Brown, Rip Torn, Mare Winningham, Tom Conti, Fernando Rey, Erland Josephson, Giancarlo Giannini, Farrah Fawcett, Alfre Woodard, Sônia Braga, María Conchita Alonso, Tom Hulce, Ray Liotta, Jamie Lee Curtis, Halle Berry, Jimmy Smits, and Sherilyn Fenn. He also directed Paul Simon in the film Simon wrote about the music business, One-Trick Pony (1980), which included the film debut of Lou Reed, playing a music producer.

Whether tackling the lives of Lower East Side Jewish gangsters, impoverished Sicilians, Southern African-Americans, Puerto Rican inmates, Mexican immigrants on the run, Upper West Side rich kids, et. al., Young brought a signature gusto and a genuine love for humanity to every project he undertook.

Actor/director Edward James Olmos, whom Young cast in eight films and whose directorial debut Young produced, chose Young as his favorite director in the “What to Watch” section of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science website, which highlights “what films filmmakers are watching.”

“My favorite director of all time,” writes Olmos.