Back to selection

Back to selection

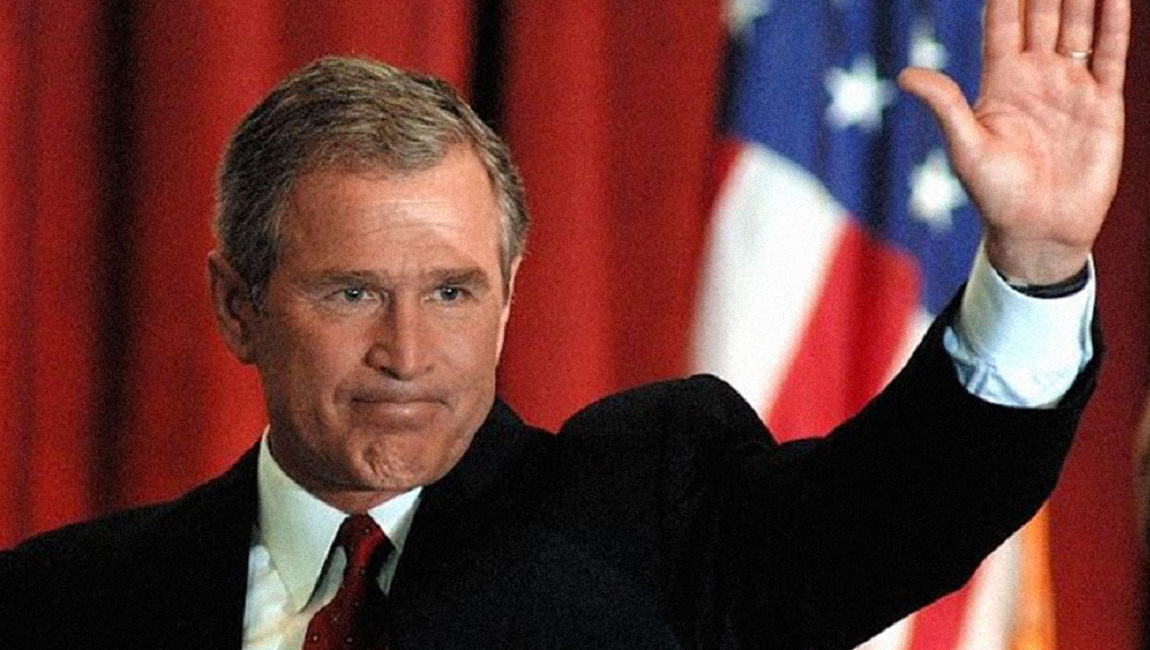

The Devil, Most Definitely: Christopher Jason Bell on His Ten-Part Archival George W. Bush Docu-Series Miss Me Yet

Miss Me Yet

Miss Me Yet “When George W Bush becomes president, for the first time, I knew someone dumber than me was president, and the whole fucking thing fell apart. It’s all been a house of cards, it’s all been a shell game, and a mirror illusion, and George W. Bush made it so you could finally see through the mirror, at all the wrong angles.” — Quentin Tarantino.

Over the last four presidential administrations, Christopher Jason Bell has produced an estimable body of work, directing more than13 shorts and three features, devoted to creating off-beat, experimental, and challenging microbudget cinema, spanning narrative, documentary and hybrid forms of both. His most recent work, Miss Me Yet, is an epic, thoughtful, and disturbing archival journey through the reign of George W. Bush, whose status as ‘Worst President Ever’has largely been forgotten in the wake of the Trump regime.

Divided into ten episodes, Bell’s series is exhaustive and unflinching. It includes a trove of never-before-seen material, including graphic war-zone footage of Afghanistan and Iraq, and the historic moment in the Florida 2000 electoral crisis known colloquially as the Brooks Brothers Riot. Miss Me Yet also takes chances other filmmakers in Bell’s place either can’t or won’t, and it’s these choices which separates the series from the archival pack and make it an essential viewing in these volatile-feeling electoral times.

Filmmaker spoke to Bell from his home in New Jersey. A special screening of the full Miss Me Yet series plays at Chicago’s Sweet Void Cinema on September 6th and 7th. The series is available on Means.Tv to stream, and tickets and details for the 9/6-9/7 shows at Sweet Void can be found here.

Filmmaker: There’s so much to begin with, so as a jumping off point, let’s talk about your entry, or perhaps more accurately, your descent into this project.

Bell: It was around 2013 or 14 when you really saw a concerted effort in the media to rehab George W. Bush. [He was] jovial, he painted, [and the narrative was] “He did the best he could, Cheney was the real villain.” I had an idea to do an all archival doc — no voiceovers, no little animated segments, no interviews — that started with him as president, including all of the destruction his presidency wrought, and ended with him on Ellen. I couldn’t shake it, and nobody else was making it, so I figured it would have to be me. So I started in earnest, ripping videos and watching them, in 2014, 2015. I grabbed as much footage as I could. There were obvious points to hit but I also wanted to make sure I wasn’t missing something. I wanted to find stuff outside of the usual things we all know. But… I also watched maybe 200 clips that were just [Bush] getting on and off Air Force One.

Filmmaker: Was there a point at which this was originally intended to be a feature?

Bell: Yeah, it was supposed to be a movie. It was very difficult to wrangle and a fellow filmmaker, Zach Fleming, gave me feedback on a cut and suggested a series. I, of course, dismissed it immediately… But then thought about it and it seemed like the logical choice to make given the breadth of the material. This way, people who don’t have the energy to re-live the Bush years can take it as slow as they need to.

Filmmaker: In terms of authorial intent or an editorial stamp of any kind, the series shies away from any blatant political statement of opinion or allegiance for more than half of the piece. Once you do project of yourself into the actual text of the film, you do so in an unequivocal way, that is genuinely shocking when it does appear. I won’t give it away, but talk about that, if that was a conscious choice.

Bell: The point you’re talking about is funny because I never really decided if it was too cheeky or not. It’s probably both.

Filmmaker: Yeah, and I’m not going to spoil anything here, but for the first few instances where you do chime in authorially, it’s fairly objective. And then, after the Katrina episode, the choice of words on the card become so blunt and forceful, that it gives the viewer a genuine shock. It’s hypercritical of Bush but also kind of a “jump out of your chair” moment in the series. Can you break that moment down, how you got there?

Bell: I was trained in that whole slow cinema, long-take, Brechtian distancing thing. If you look at someone like Michael Haneke’s work, how he uses the effect of letting the camera linger a little too long over the end of a scene, or how it’s usually punctuated by a moment of violence…

Filmmaker: I almost screamed watching it. It’s powerful and shocking, the time it takes to get there, so that by the time this shock occurs, the viewer is somewhat lulled.

Bell: Right. So the challenge then becomes, ‘How are we going to replicate that feeling?’ The moment you’re referring to comes much later in the series, and so at that point, I’ve established rules, and now I’m going to break them. Something shatters, and you’re taken aback [as a viewer], and part of that is about holding back till you actually can’t any longer. If someone really thought about the kind of clips I’m using and including, the language and information in the title cards, they can probably figure out which side of the equation I’m on. That’s fine. That’s a subtle thing. But I’m also one to not want things to be unclear. I do want you to know: I take issue with this guy, and this administration, and even the system we live under. But how can I do that within the storytelling and the journey we’re going on? Where can I put that where it will be the most effective, and create a genuine arc for that?

Filmmaker: It’s so uncommon in documentary work in general, which so often is “journalistic” in its methodology, couched in an air of objectivity. It’s a way of remaining disconnected from having to own any kind of statement.

Bell: I think with movies and media and TV, there is an inclination to play both sides, to really hold back, and be objective, or whatever. Like, you can tell us about this politician, but you have to give both sides —

Filmmaker: Yeah, you’ve got to show him with his dog or his kids or some shit.

Bell: [laughing] There’s something interesting about that, but it’s not done in the right way.

Filmmaker: Your work here feels like a corrective to that. Like there’s a lot of things you feel nobody has said, and that you want to come out and say. In so many ways, you’re raising your hand and saying, “I’ll be the one who says it.”

Bell: Well, I mean, what does it say that there’s a guy who in a blink of an eye can drop a bomb on the home of a family, but he also loves his dog? What does it say? That’s an extreme example, you can insert whatever contrast you want, but there’s so much blood on these people’s hands, that I honestly don’t know how you can then say, “Oh, but he loves his family. Oh, but he’s a Christian, he cares about the unborn.: In the day to day, we live under so many contradictions, I mean, we’re being [so] assaulted by them everyday that it leads to insanity. It leads people, myself included, to just think the wrong way about certain things, to not step back and really try to understand how things are, how things are going. And I do really get it, because you can go so deep into learning what’s going on in the world, in our country, our country in relation to other countries, it does truly seem like we’re powerless. There’s things you can do as a person to alleviate suffering, I don’t want to minimize that at all, but the education of it all… Can be quite sad.

Filmmaker: It can feel crushing, particularly in terms of the current state of the affairs. I wanted to ask about your framing of the piece. It feels meditative, the way it returns to certain chords repeatedly. I’m thinking not only of the White House-produced home video series about Bush and his dog Barney, and the early aughts commercials and pop culture clips, but also the uncensored images of wounded Iraqi and Afghani civilians, juxtaposed with Junior clowning for the news cameras… When it comes to this kind of rhyming grammar, was that something you came to in the initial immersion, or something that took shape once you were all logged and into the edit? Was there an archival edit script?

Bell: There wasn’t really. I watched and logged all the footage myself though, even when the sources had their own log.

Filmmaker: And was it always episodically broken up year by year?

Bell: Some of the things that happened every year were shoe-ins — The Barney videos, for instance — but otherwise, I kind of just went in order for each given year and cut accordingly. Every video had a date, and I laid it all out in order. You try for the obvious things — is this too much, is this too boring, is this too gruesome — and then you see which clips speak to one another, how they flow in and out of one another shot-wise.

Filmmaker: In terms of sheer size, the magnitude of the series is kind of staggering. I definitely marveled at how much you must have had to sit through, just to be able to see a through line and put it together conceptually. Do you think your background, working in archival materials, but also in more experimental, hybrid docs, helped you make sense of it all?

Bell: I’m not sure how my experience as a filmmaker — whether it’s in documentary, archival materials, working with non-studied actors, etc — helped. Maybe my joy in diving into the unknown or allowing happy accidents and stuff to come into play helped me. It was a pretty gargantuan task. I guess I’m patient and committed to seeing things through. I think also it was unclear what kind of release this would get because of the nature of using lots and lots of material I did not own. Being a part of MeansTV was a great help because this could probably be on YouTube or something for a short amount of time, but there would be no push to get it seen.

Filmmaker: I found the entire piece incredibly haunting and disturbing throughout. It’s not just because of how ominous it all seems, how unconcerned Junior and his administration seem to be with the damage they’re doing, but also how gleefully evil they seem at times.

Bell: I would say that you would have to go a few decades for me to be okay with a US President. They would have to be, at the very least, part of the New Deal tradition, and even then they are committing gnarly acts of destruction in Vietnam, for example. So I don’t really have a good view of them in general. But… Yeah, I’d say George W. Bush was really bad.

Filmmaker: But even in comparison with other war criminals, the Bushies come off as very much in love with the feeling of glory and might that was attendant to their moment in power.

Bell: I hope in some way the series encourages people to learn and do more, I don’t know how, but I tried to make it so that not only are the people working under George W. Bush implicated, but the entire system is too. It can’t be “Oh ,Bush is bad, if we just had another guy it would be okay.” Having someone different in the halls of power does make a difference but it also can do only so much.

Filmmaker: Episode 10 deals with his public image renovation. I thought of this many times during the Trump years, when people would outlandishly swear up and down — many still do, frustratingly — that Trump was just the worst person to ever even come close to the job — and every time I’ve encountered this, I had the same reaction: They seem to have forgiven Junior.

Bell: I think, in general, day-to-day contradictions of the system we live under make people generally confused and muddled…

Filmmaker:It definitely seems like the turnover rate in people’s minds is quite rapid on the small scale, in terms of what the most pressing issues are, whether in an election year or a presidential term. When they pave over history, it happens without people noticing.

Bell: And stuff like the 24-hour news cycle, the Internet, social media… It just makes that problem two hundred times worse.

Filmmaker: In the last eight years, since Trump took power in 2016, it does feel like we’re in danger of forgetting. Miss Me Yet essentially posits that it’s Junior’s world, and the rest of us are just living in it. So while Trump’s taken on this boogeyman role in the culture, that’s dangerous, because it takes responsibility from those who should shoulder the lion’s share of the blame for how things are in the world.

Bell: I think we generally don’t have a good cultural memory for things that were like, last year, because we’re constantly bombarded with the present reifying itself. I also think sometimes news, or even documentaries, do kind of exhibit things in a vacuum.

Filmmaker: Let’s try and center you in the middle of all of this. Tell us about where you were when the Bush regime was in power. You were in college?

Bell: I was, for some of it.

Filmmaker: And were you politically oriented?

Bell: Yes and no. I was kind of searching for it, because I was very confused with the way that people, the way the world was telling me that things were. Nothing makes sense to me now and nothing made sense to me then. Then 9/11 happened, and it was hard to talk to anyone about it, certainly being from a small suburban town. The sentiments were pro-retaliation, which lead then to being pro-Iraqi invasion.

Filmmaker: Were you involved in any activism at that time?

Bell: I was vegan, so in my mind, I was voting with my dollar. But that was about it. I wasn’t really involved in protests or anything like that. Growing up, I’d had a fairly strict upbringing, so I wouldn’t have been encouraged to go to protests, to be involved in that way. When I got out of school I began to read more and learn more. So I learned how to talk about these things way after the fact. This project is a way of looking back and situating myself, the way so many of us saw that was going on was something very wrong and felt weird [in the government], but didn’t know how to talk about it, think about it, or even be able to ask the question as to why we couldn’t talk about this, or even think about it in a different way. The [American] hegemony, through media, reifies certaing things and takes certain things off the table in terms of discussion. The whole series is constructed in a way that tackles the things I felt for such a long time, even back then.

Filmmaker: The series’ edit is extremely dialectic in terms of juxtaposition. The contrasts say a lot without your saying it directly.

Bell: Well it’s not that the images do the talking for me: It’s their placement.

Filmmaker: That construction feels purposeful in a way that presents as a political statement.

Bell: The whole idea is to recontextualize this man in power, this administration, and even this very system. Now, that means you have very obvious things — i.e. Bush says, “Hey, these guys are so violent,” and then you cut to a community of people that have been bombed by America — and maybe that feels like a cheap technique, but at the same time, let’s think about it and take it seriously.

Filmmaker: And the way its designed, there’s no getting away from your point of view. Contrasting these banal proclamations that Bush would make on camera with visceral footage of civilian casualties and the wounded, the direct result of policy and concealed by that form of public address, it’s powerful.

Bell: I think it’s also less obvious when I do contrast two things in an episode in minute two and minute ten, or when I do it in Episode 2 and Episode 8. The entirety of it is in conversation with itself, and I think that process of absorption in the viewer — that conversation, really — goes deeper.

Filmmaker: Are there other docs you connected to in making this, or on the way to this?

Bell: Well it was so long in percolating. I was working on it since 2014, and I was watching a movie a day. I would see things that I felt were on the same wavelength, stuff like Spin [1995, Bryan Friedman] and Feed [1992, Kevin Rafferty, James Ridgeway]. And also Harun Farocki’s stuff, which I came into way late, but someone I trust mentioned me that the project sounded like his work. I also love slow cinema, I love sitting and watching something, waiting for something to happen for so long that you get distanced, and then drawn back in. For me, there’s this incredibly interesting play [in that experience] — and with the footage, I thought I was going to be sifting through a bunch of stuff with Bush just sitting around. And it wasn’t that at all. He was talking, at times non-stop. Always talking. So I think the premise with Miss Me Yet became recalibrated into, “How do I do a slow cinema thing with footage of a guy who’s always talking?”

Filmmaker: Someone who never shuts up.

Bell: [laughs] Yeah, so I felt my way into it from there. Voiceover was never going to come into it. There are expectations going into it that there’s going to be more handholding than there actually is, but me, when I’m watching documentaries and I see that, and it’s like, you’re doing too much here. You’re not letting the thing speak for itself. You don’t need to do that. You can take it away. So I guess I’m drawn to minimalism, even if only just by design, when it comes to not having many resources to work with. But I do believe that these images speak for themselves, and if you put them together, it says a whole lot.

Filmmaker: It definitely says something different than each image on its own.

Bell: Yeah, and I also think, with longer form storytelling, you can create callbacks to previous episodes, or even within the same episode, that you can’t do with something that takes less time.

Filmmaker: What’s the total running time, all in?

Bell: It’s close to four hours.

Filmmaker: I watched it that way, but lost track of how much time passed.

Bell: Dirty little secret, but it was hard to whittle down. I think the feature version clocked in at around two-and-a-half hours, and even then, there was a lot of stuff that I wanted to include but had to take out. So part of reimagining it as a series, was that then I could put a lot of that stuff back in. Now that it’s broken up, it’s a lot, but it makes more sense that way. Even at two-and-a-half hours, you can still imagine someone watching it in a theatre all in one go. But I didn’t want it to feel like… I was at the NYFF press screening of Bela Tarr’s The Turin Horse, and when the third title card came up and there was still an hour left, there were a lot of groans.

Filmmaker: [laughs] What would you do differently if you had to take this kind of thing on again?

Bell: Well, at a certain point I had to accept that I could only do so much with this kind of project. It was always going to be big, but I could only put so much in. Even just by the nature of what’s on video, or the aesthetic principles that I established for the project, I couldn’t go too crazy with any of it. There’s always stuff I wish I could have included. Every few months, I think, should I do another episode? But there’s a part of it that I’ve come to terms with. I don’t want to put it too much on the President, and then inadvertently absolve the people around him or the system. Hopefully people will get more out of the series than just that. I get it that it’s about Bush, the poster has Bush on it, the title is a reference to Bush. But it can’t be everything. The narrative is overwhelming, and yet also sometimes pretty disappointing. There is so much that is completely not on video or not sufficiently on video that I had to leave out. I could only go so far by nature of the parameters I set. That’s something that still disappoints me, though I half made peace with the fact this series could not be everything.

Filmmaker: The view of Bush as being somehow delimited or unintelligent seems to have fed pretty nicely into this fuzzy, cuddly, modern version of him we have now.

Bell: Well that’s the reputation rehabbing… The messaging was always that, “Oh, Bush is dumb,” or, “Oh, poor Bush, he was taken for a ride…” And it’s just like, this is his ideology too. Let’s not absolve him. What does it say about a person, that he can talk about the unborn, how he cares so much, but then he’s part of a movement that not only decimates social programs but drops bombs indiscriminately.

Filmmaker: Wreaking havoc worldwide.

Bell: And it doesn’t bother him. To this day. I don’t know how else to say that. I don’t want to be like, maybe it’s different from the executive seat… Because I don’t really care. Who am I, who is Bush to say these lives we took were worth it? It’s like, what are you trying to accomplish under the expense of inflicting complete misery? What are you trying to maintain by destroying so much? And I don’t think he should be absolved just because he’s charismatically goofy.

Filmmaker: He gets away with it in the end. But hey, if the ending of the series is to be taken at face value, then he’s the devil… Probably.

Bell: [laughter]

Filmmaker: I’m half-joking, but for real, you have one of the most disturbing endings in recent memory. That image will live in my mind for a long time…

Bell: Thanks, I think.