Back to selection

Back to selection

“Bringing Light to Darkness Does Motivate My Choice”: Editor Don Bernier, Life After

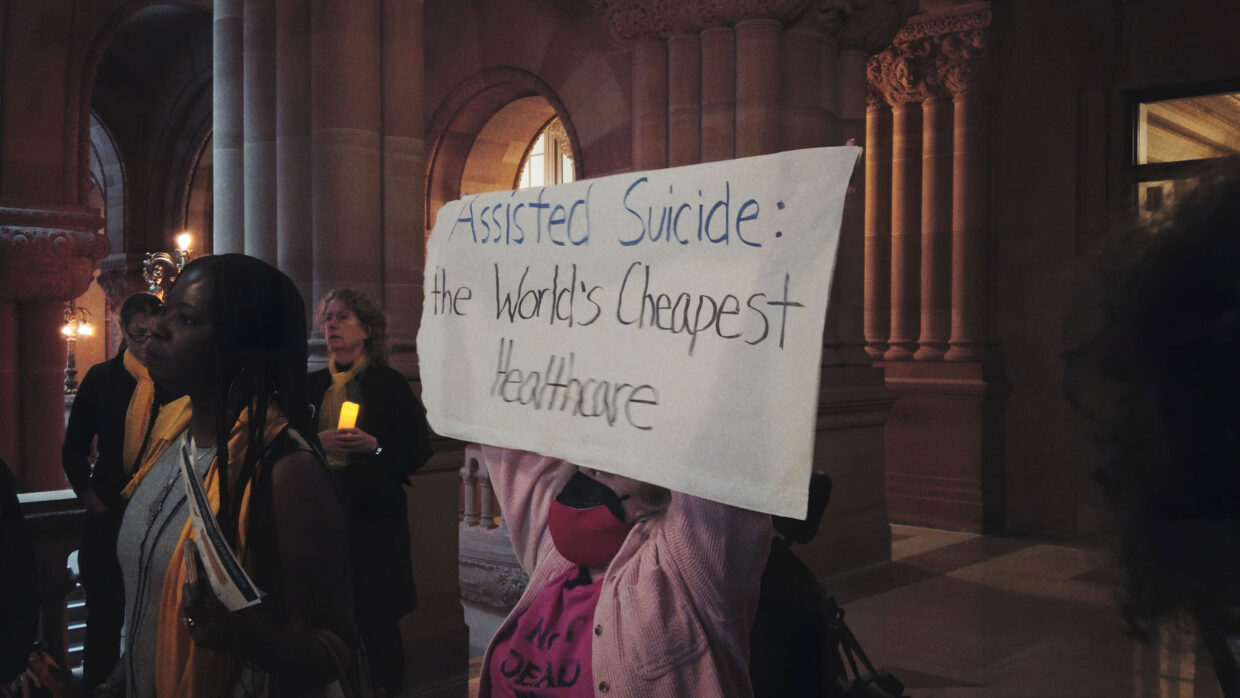

Still from Life After. Courtesy of Sundance Institute.

Still from Life After. Courtesy of Sundance Institute. Reid Davenport’s follow-up to I Didn’t See You There probes the intersection between disability rights and medical assistance in dying in relation to the case of Elizabeth Bouvia, who started a national conversation about the issue in 1983 that persists to this day. The film screens in the 2025 Sundance Film Festival’s U.S. Documentary Competition.

Don Bernier (Athlete A, An Inconvenient Sequel) served as the film’s editor. Below, he explains how working on Life After altered his view on the subject and connects the fine arts and experimental film that sparked his interest in film with documentary editing.

See all responses to our annual Sundance editor interviews here.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the editor of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Bernier: I’d worked with Multitude Films previously on another Sundance doc called Always in Season, directed by Jackie Olive, in 2019. I’ve been wanting to work with Jess Devaney and her team again ever since. Producer Colleen Cassingham reached out to me in the fall of 2023 and said they were looking for an editor for Reid Davenport’s latest feature, Life After. I’d watched Reid’s I Didn’t See You There the year before and it was by far one of my favorite docs of 2022.

“What’s your film about?” I asked Colleen. “Assisted suicide and the disabled community,” she began. At the time, I was wrapping up a very intense film about the physical and psychological trauma special forces veterans sustained during the 20 year “War on Terror.” Before that, films I’ve edited have tackled gun violence, lynching, sexual assault, Ebola, Alzheimer’s, homelessness and climate change. So, I had told myself I wouldn’t take on another job with such intense subject matter for a while. But, by the time I got off the call with Colleen and Reid I knew I had to edit Life After. The under-reported dangers of assisted suicide laws to people with disabilities based on the devaluation of their lives enraged me. Bringing light to darkness does motivate my choice when picking a new project.

Additionally, meeting Reid and knowing that there might be a personal element to the film in him investigating Elizabeth Bouvia’s 1983 right-to-die case via archival footage and on-screen “detective” work also lured me in. I always love the chance to weave together multiple storylines!

Filmmaker: In terms of advancing your film from its earliest assembly to your final cut, what were your goals as an editor? What elements of the film did you want to enhance, or preserve, or tease out or totally reshape?

Bernier: Since we had so many potential strands to consider, we first cut long assemblies of each archival and verité storyline. Then we watched them all together in no particular order. My goal was to get an initial sense of which stories were the most intriguing and which ones didn’t exactly fit or propel the larger narrative. The biggest discovery was that the Bouvia strand had an emotional punch and could be developed further as the film’s backbone. Since it incorporated both archival footage and active verité of Reid, Colleen and Bouvia’s sisters, it was rich with potential. And so, fairly quickly, we were able to shed a few less crucial stories and expand our primary narrative. Then the challenge was to weave our little galaxy of remaining storylines around Reid and Bouvia.

Filmmaker: As an editor, how did you come up in the business, and what influences have affected your work?

Bernier: I think I always knew I’d be involved with editing film and TV, but in many ways, I sort of backed into it. In 1988, I went off to a small art school in the Midwest and got into experimental film, video, photography and installation art. I didn’t attend “film school” and study the Hollywood masters. Instead, I was watching Bill Viola and Su Friedrich. Later, after I realized how hard it was to survive solely as a visual artist, I taught video production and editing for a while, but it was primarily technical and not very satisfying creatively for me.

After moving to New York in 2001, I’d set out to be an assistant camera person when I accidentally found myself working as an assistant editor on a documentary series for PBS. For nine months, I worked a graveyard shift in a Hudson Valley shack converted into an edit room. But it was inside those crowded little walls, assisting two talented editors who have since become great friends of mine, that I found my place. Ever since that first AE job, I’ve persisted in editing documentaries. It’s both a passion for me and a creative outlet. Editing really is an artistic practice, much like building a sculpture. In 2007, I moved back to the Bay Area and have been cutting features, series and shorts ever since.

Filmmaker: Finally, now that the process is over, what new meanings has the film taken on for you? What did you discover in the footage that you might not have seen initially, and how does your final understanding of the film differ from the understanding that you began with?

Bernier: I always try to at least know something about the subject matter going into a new project, and then I read a lot about the topic/s, and then I immerse myself in the raw footage and in dialogue with the director. And with every film, I learn so much more than I thought I knew when I began the collaboration. Life After was a glaring example of this for me. Like many people I know, I thought my initial perception and understanding of the terms “assisted suicide” or “medically assisted death” was pretty clear: All people deserve the right to decide how they will live, be treated, and ultimately die if they’re terminally ill. From a disabled person’s perspective, the many layers of ableism that actually surround this practice were definitely new to me. For many people living with disabilities, the danger of medical discrimination is very real.

While crucial support services are being cut from state, provincial and federal budgets, medically assisted dying laws can normalize suicide as an option for a particularly vulnerable part of the population. I hope this film sheds light on this complex topic and helps society have a broader understanding of how new so-called “death with dignity” legislation affects all of us.