Back to selection

Back to selection

“It Carries the Weight of Improvisation but Also Inevitability”: Liryc Dela Cruz on his Berlinale-premiering Where the Night Stands Still (Come la Notte)

Where the Night Stands Still

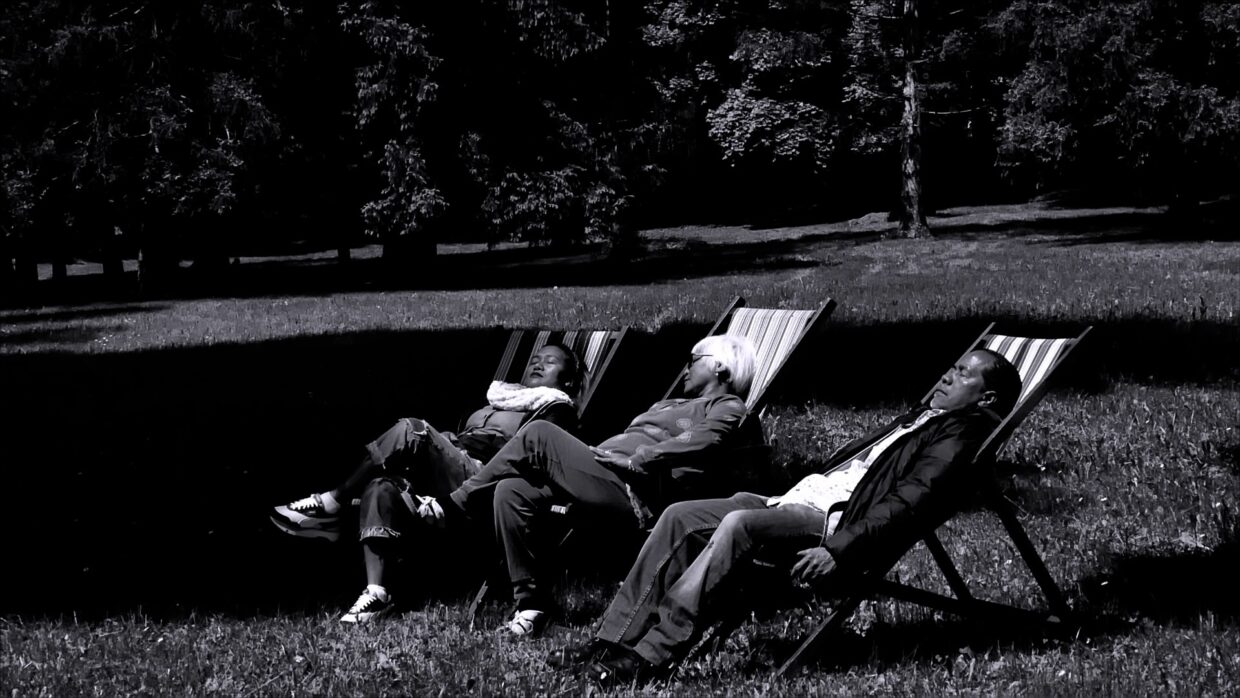

Where the Night Stands Still Liryc Dela Cruz’s Where the Night Stands Still (Come la Notte) takes the simplest of storylines and renders it infinitely complex. Three Filipino siblings, all domestic workers in Italy who’ve not seen each other for years, reunite at an extravagant villa the elder sister inherited after the death of her longtime employer. They reminisce about childhood over Filipino delicacies the younger sister and brother have brought, and stroll the vast grounds that the new owner meticulously preserves as if she were still a servant and not the lady of the house. But as the languorous day draws to a close tensions build, conversations turn, and buried grievances emerge. All of which is meticulously captured in haunting B&W, the ghosts of the past present in every striking frame.

A few days prior to the February 15th Berlinale premiere of Where the Night Stands Still (Come la Notte), Filmmaker reached out to the film’s director (and producer, writer, editor and DP), an artist with roots in both the Philippines and Rome, about his thrillingly auspicious feature-length debut.

Filmmaker: So how did this film originate? Did it grow out of your first solo exhibition, Il Mio Filippino: For Those Who Care To See?

Dela Cruz: Come la Notte was never supposed to be the Come la Notte that exists today. The film was shaped by an emergency the night before shooting, when before traveling to the location the original protagonist’s son contracted COVID. In that moment everything shifted, and we had to rewrite the story on the way to the set. We drew from the shared narratives that have always been present in our conversations, lived experiences, hearsays, and the unspoken realities that circulate within the Filipino community in Italy.

This process of reconfiguration wasn’t unfamiliar to us. My first solo exhibition, Il Mio Filippino: For Those Who Care To See, was also about disrupting fixed narratives and questioning how the Filipino laboring body is perceived in the West. That project engaged with archival images and performative gestures, but Come la Notte moves deeper into the emotional and psychological spaces of migration, estrangement, and the weight of unspoken histories.

In reworking the film under such urgent circumstances, we instinctively merged real stories with my literary references, and fragments of works that have shaped us. The result is something both deeply personal and collectively constructed. It carries the weight of improvisation, but also of inevitability, because these are stories we have always known. They live in our community, in our silences, in the way we endure. The film became what it needed to be, shaped by the very forces it seeks to explore: uncertainty, survival, and the constant act of rewriting oneself in a foreign land.

Filmmaker: Could you talk a bit about your relationship with Il Mio Filippino Collective, which is comprised of “Filippino domestic and care workers, artists, community organizers and members of the diaspora based in Italy,” and collaborating with them on this film? I noticed your three protagonists all developed the story, and are credited as crew.

Dela Cruz: I cofounded Il Mio Filippino Collective unofficially with the cast members in 2018, alongside fellow domestic workers, artists, and community organizers in Italy. Then in 2020, we formalized the collective. The primary concern of the collective was to challenge and recenter the narrative regarding the invisibility of care and domestic workers as a major workforce in Italy and other Western countries. A key figure in shaping both the collective and this film is Benjamin Vasquez Barcellano Jr., who plays Manny. Beyond his role in the film, he is a committed community organizer in Rome. He was the one who connected me to many members of the collective.

I, too, have done domestic work in Italy. This reality is not foreign to me; it informs my perspective and my practice. Because of our shared experiences, working on Come la Notte felt intuitive. We have known each other for years, collaborated in performances, and built trust through artistic and community work. I deeply respect the intelligence and creativity of my collaborators. They allow me to be the wild crazy kid that I was when I met them, while also holding me with care, patience and love. With them I’ve learned more about what it means to be human.

The process itself was fluid and organic. On the first day of shooting, I was still handling almost everything. But soon they fell into rhythm with me, understanding the cadence of how I imagined the film. Most of the dialogue felt natural because it came from words we’ve spoken, overheard, or carried with us. I encouraged them to interpret their characters freely, using their own instincts and histories as primary tools. This unstructured approach, where the film unfolded through intuition rather than rigid planning, became an act of emancipation. I credited them in developing the story because it was shaped in realtime. On set, we were constantly discussing, reworking, and pulling from past conversations. I would recall something from our shared moments and ask if they could inject it into their characters or use it as a narrative device. We were a small crew, just five people, so multitasking was essential, much like in our performances.

But beyond practicality, this way of working was transformative. It proved that Filipinos are not confined to the reductive roles the West has assigned us. The “Filippino” are more than what racist and colonial structures dictate; we are artists, storytellers, and creators of our own myths.

Filmmaker: In addition to being an artist and filmmaker you also founded a production company, Pelircula, which is expanding internationally. So what sorts of projects are you developing?

Dela Cruz: We want to examine how power constructs identities, how myth and propaganda shape reality, and how colonial legacies continue to manifest in the present. One of our upcoming projects, Paradiso Orientale, explores the fabrication of the Tasaday tribe in 1971, and how figures like the late Italian actress Gina Lollobrigida were used to legitimize this Marcosian spectacle. The film follows Donatella, an Italian actress who, after documenting the tribe, returns home only to experience a haunting physical decay, her body rotting as if cursed by the lies of history. It’s something very close to me because Gina Lollobrigiba went precisely to my hometown of South Cotabato in Mindanao, Philippines during that period. So it excites me a lot to bridge this story.

Filmmaker: I’m also curious to hear how audiences from Western countries versus viewers from colonized nations respond to your work. Are your messages different for each?

Dela Cruz: The responses are often quite different, though not always in the ways one might expect. Viewers who share the same sentiments with us, especially people who have a strong colonial history, often recognize the weight of history and labor in our works intuitively. They see their own families, their own stories, even in the silences. There’s less need to explain the nuances of migration, care work or colonial residue — it’s already part of their lived experience. Sometimes they tell us our works make them feel seen; other times it reopens wounds they’ve been trying to forget. Either way there’s a deep, visceral recognition.

Western audiences, on the other hand, often approach our works with a certain distance. Some are deeply engaged, especially those attuned to decolonial thought, while others struggle with the contemplative rhythms or the lack of clear exposition. There’s sometimes a tendency to exoticize or intellectualize the Filipino experience rather than feel it. But I don’t shape my films or work differently for them. I don’t believe in translating or diluting for a Western gaze. The work remains the same. It’s rooted in Filipino experiences, told in our rhythms. If Western audiences truly want to listen, they have to meet the film where it stands.

That said, I do find it interesting when Western viewers connect with the themes of alienation, family fractures, and longing. It reminds me that, despite the vast differences in history and privilege, displacement, whether literal or emotional, is something many people carry in different ways.

Filmmaker: Finally, what are your — and the Collective’s — ultimate hopes for the film (which you refer to as a “cautionary tale” in your director’s statement)?

Dela Cruz: Our hope for Come la Notte is that it exists as both a whisper and a cautionary tale. A whisper because it speaks in quiet moments of siblings who can no longer find the language to bridge the distances between them, of bodies that carry the weight of history without knowing how to set it down.

The film is a microcosm of the world we live in, a reflection of a larger darkness. We like to believe that we have moved forward, that history is behind us, that the violence of the past belongs to another time. But the night is still here. The same forces that uproot, erase and consume remain at work, only shifting their masks. Is the world truly changing, or have we simply become better at looking away? If we are no longer haunted by ghosts, is it because the ghosts have stepped fully into the light? We call it a cautionary tale because it confronts us with a question: If we claim to be post-colonial, post-dictatorship, post-trauma, why does the architecture of violence remain intact? If history is cyclical, does that mean it is inevitable, or does it mean we have failed to intervene?