Back to selection

Back to selection

“There Was No Going Around Gaza”: Raoul Peck on Cannes 2025 Premiere Orwell: 2+2=5

Orwell: 2+2=5

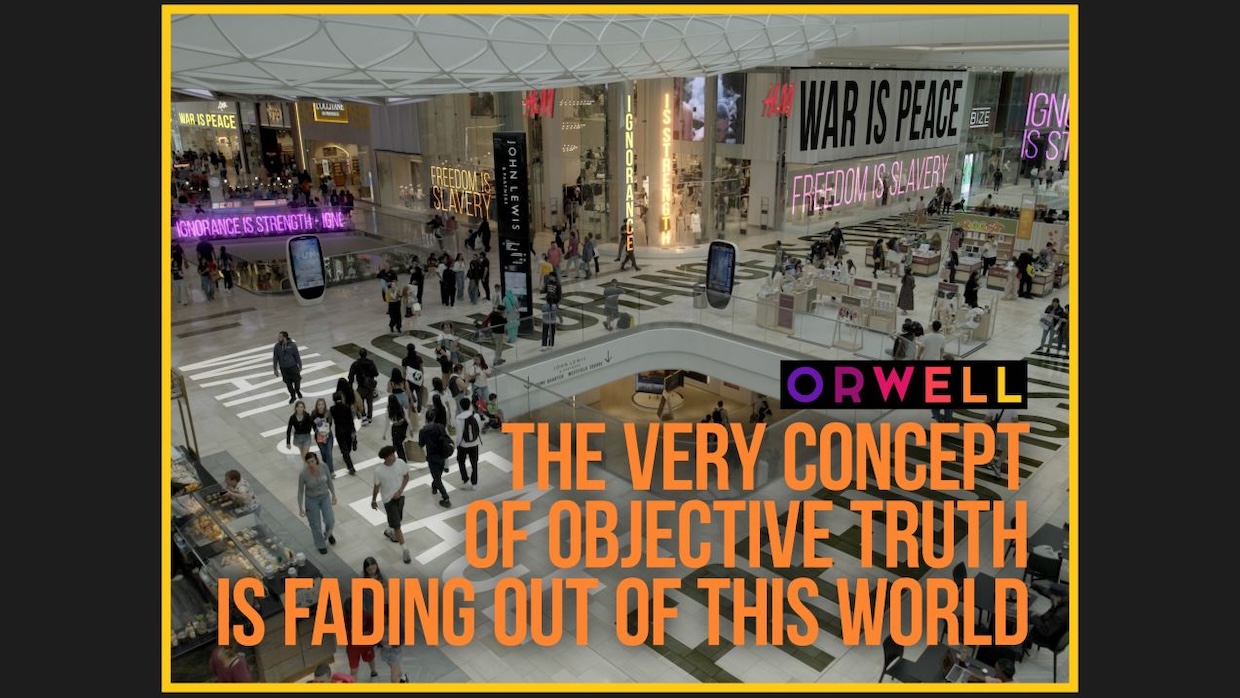

Orwell: 2+2=5 Raoul Peck’s new documentary Orwell: 2+2=5 opens with a credit sequence featuring images of what appear to be microscopic larvae wriggling across the screen. The message seems clear: something nefarious is afoot on this globe, but still in its incipient stages. If we fail to act, it’s going to get much worse.

In recent years, the filmmaker has made direct, no-nonsense use of the nonfiction form to address, from various angles, the rot of white supremacy, its historical roots and its unchecked future. Building on I Am Not Your Negro, Silver Dollar Road, the miniseries Exterminate All the Brutes and last year’s Ernest Cole: Lost and Found, Orwell uses the famous writer’s letters, essays and novels to illustrate the clear rise of a new global fascism in the classical mode. 2+2=5 incorporates contemporary archival footage and portraiture from Myanmar and India, countries which played an important role in Orwell’s biography (he was born in the latter and did colonial military service in the former), but also Iraq, Tunisia, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine and Gaza, among others—not to mention America, where Trump’s bluster and the events of January 6 feature heavily. Tracking Orwell’s evolution from dutiful imperial subject to concerned global citizen, the film seems to offer hope that even some oppressors among us might awaken to pangs of conscience.

Filmmaker: On a certain level, Orwell makes perfect sense as a proxy for investigating the current moment. However, you’ve chosen to use not just 1984, the most obviously invoked parallel, but Orwell’s larger biography and the reflections he wrote in the form of letters at the end of his life. The cumulative effect is that we see the awakening or reforming of an imperial conscience—somebody who was born in the heart of empire and who himself exacted violence on its behalf coming to acknowledge its malicious and destructive nature. Where did you begin with the many facets of his life and work? What was your way in?

Peck: In order to make my films, I have to reappropriate the subject, to make it mine. For Orwell, I found very early on in my research the link we had—going to Burma. He discovered The Other in Burma. Even though he was on the imperialistic, repressive side, he became a different human being. He reflected on what he was doing and discovered that, “No, I’m not that person. This is crazy, and the wealth of my country is based on that.” He was 18. What people have made of Orwell over the years was to put him in this little tunnel of anti-Sovietism, anti-Stalinism. As if it’s a Russian speciality. No, it’s the whole planet. Any power is subject to becoming authoritarian.

Filmmaker: That’s why you focus on the larger context of his biography.

Peck: I had access to everything. Usually when you buy rights, you have access to one novel or text, so that’s being in the toy room. I had to revisit everything. I had to understand my character—his psychology, his life, his biography. And I’m not making a biography, right? I’m telling a story while using exclusively his writing; that was also a decision from the start. There is not one single phrase that is not from Orwell. It’s having a lot of puzzles, and you write a screenplay with those puzzles.

Filmmaker: Were the rights to the work of Orwell something that fell in your lap or something that you sought out?

Peck: They offered it to me. They offered it to Alex Gibney, who called me the same hour. He said, “Orwell. Are you in?” That was it. You can’t refuse. Orwell, come on. I had no clue at the time what film I was going to make.

Filmmaker: The structure has several layers. On the one hand, like you said, there’s the actual words of Orwell through the letters he wrote and his novels, but you also have elements of his biography, contemporary archival footage, and then the portraits. And you use the precepts “War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength” from 1984 to structure the material. How did you begin to create that framework?

Peck: The first step is always to go through the text. I take multiple pen colors and go through again and again. Since I became a filmmaker, all my films [have been] conceptual, so I know when a sentence is impactful and when a sentence is universal. I say, “How can I extract the purest of Orwell to tell the story?” The story is his, because he’s the one telling it. I don’t want to speak in his place. I have to be fair with his thinking; I don’t want to use him to do whatever I want. I’m like an actor trying out a character, trying to be as close to that character as I can. I study, try to understand where he was born, what his motivations were. How did he change? Once you have that, you can write the screenplay. There’s no [talking head interviews]; I don’t need the experts. I have the real person, I don’t need analysis. I have to respect the person’s words, the person’s writing, what he says about himself, what he says about the world.

Filmmaker: The key signifier of Orwell as a character in the film is not even any of his words, but this image that you show at the beginning and the end of Orwell with his Indian nursemaid. How did you how did you stumble upon that, and how did that become a focal point?

Peck: It’s a slow construction. I start with a few big ideas; I have Burma, an important location. That’s why I had teams in Burma, even though it was difficult, it was dangerous. I knew Barnhill [where Orwell spent his final years and wrote 1984] was an important location, where the character is in the moment of choice and change in his life. He’s going to die, and still has to produce this incredible material. Once you have that, you dig into the text, and then in the archive I bumped into that photo. I had seen it before, but never it in that context. I knew it [would be] there at the beginning. And then, it took me time—I had multiple endings, and [then] I said, “No, this is the photo.” The photo explains it all— this white little baby with a dark Indian woman. The Indian woman is looking straight to the camera and that fragile white little baby is all the absurdity of the world. She’s a quasi-slave and you give her your most precious little thing—what does it say [about] the craziness of the world? I’m sure there are audiences who will be shocked. I know because I tested the film, and a lot of people were shocked, but they don’t know why they are shocked. It confronts you to who you are at the core, or what you have become at the core. How do you react?

Filmmaker: It’s a person who’s supposed to be invisible in this existing power structure confronting you directly.

Peck: Yeah, and the power that person has. And that person doesn’t use that power, because destroying a baby—she tells you “Yeah, I could, but I’m more human than you, because despite what you do to me, I still prefer to be human.”

Filmmaker: As mentioned, you zero in on these places connected to Orwell’s life. You’re in Myanmar, so you have excerpts from films like Myanmar Diaries. You’re in India, so you have footage of Modi and RSS. How did you go about deciding the countries and atrocities to incorporate, and how to make connections between them?

Peck: Once I have a text, I have what I call a scenario, and usually while I’m doing it, I have a second column where I put images. I have an incredible archive in my head; I’ve been dealing with archives since I was in film school, I used to go to all the archive agents, so those are all inscribed in my head. I know all the archive from the third world, the archive of the Shoah or of the war. I went through all the colonial archive, whether it’s Congo, Asia, India, And I watch the news every day. I read three newspapers in the morning. It’s not easy, but I have this bank of images in my head. So while I’m working, I can put an idea, and then by the end of the scenario, many ideas give a framework. And then my team of archivists— who are people who have done eight, nine films with me, they know what I’m looking for— tell the archives to look for that. Then we test them, which one tells the story the best. It’s a mixture of having a core idea and conflict between image and words. Sometimes it just fits directly, and sometimes I choose the words right. There is a passage in 1984 where Winston is writing at the beginning of November: “I went to the cinema last night. There was a film about refugees in the Mediterranean.” Every day there are hundreds of people dying in the middle of the sea, so that’s our relation with those events.

Filmmaker: You incorporate footage of Gaza very prominently throughout the film. What was your thinking and process around that?

Peck: There was no going around Gaza. You cannot unsee those images of a city that just disappeared. Everything that happened in Gaza has basically touched the definition of genocide. I am probably one of the filmmaker[s who’s worked the most on genocide]. I studied the guy who invented the word “genocide.” All the signs and the proof are there. I just describe what I see. You can’t tell me I didn’t see that. It’s not about taking sides, it’s about telling the truth, and there is something that’s called objective truth. That’s also what Orwell was after, objective truth.

Filmmaker: Your signature portraiture footage is also featured in this film. Your portraits that tend to lend an extraordinary dignity to your subjects, very memorably at the end of I Am Not Your Negro, for example. What’s interesting here is you have portraits of what we might call oppressed subjects, but then also portraits of MAGA figures. Can you talk about engaging them?

Peck: The portrait is always to keep humanity close. It’s about human beings. We cannot let that link go. Even the MAGA crowd, I sent a crew to the Republican Convention. I needed those images, because it’s not about saying they are bad people, right? I have to take them into account too. I don’t want a separate world. If we want to live together, we have to live together. We just have to find a place where we can argue, so I had to include that. It’s not about making enemies. Attachment to humans is the whole film; whoever you are, whatever colors you are, whatever class you are. It’s about our civilization, and when I say civilization, [I don’t mean] Western civilization, but human civilization.

Filmmaker: Your last fiction film was The Young Karl Marx in 2017. Do you have any others in development?

Peck: I have five films waiting to be financed. I have a film called Black Generals about the Haitian revolution that I wrote for Amazon, then I tried to make it with Apple but they said they were already doing something on the subject—which was Napoleon. So that tells you what the fucking situation is!