Back to selection

Back to selection

Tony Gerber & Jesse Moss, Full Battle Rattle

A strong partnership always relies on both individuals bringing different things to the table, and documentary filmmakers Tony Gerber and Jesse Moss certainly draw on diverse backgrounds for their creative collaboration. New York City native Gerber began his career directing alternative theater and making films for theatrical productions, and went on to work with conceptual artist Matthew Barney on Cremaster III (2002) and Drawing Restraint 9 (2005). He directed the short film, Small Taste of Heaven in 1997, and his debut fiction feature, the Merchant-Ivory produced Side Streets, followed a year later. In contrast, Moss began as a Capitol Hill speechwriter but quit political life to work for legendary documentarian Barbara Kopple. Beginning first as a producer, he made his directorial debut with Con Man (2003), the story of Princeton hoaxer James Hogue, and also completed his second film, the demolition derby documentary Speedo, the very same year. Gerber and Moss met in 2004 when Gerber, then an executive at AMC, commissioned Moss to make Rated ‘R’: Republicans in Hollywood for the network.

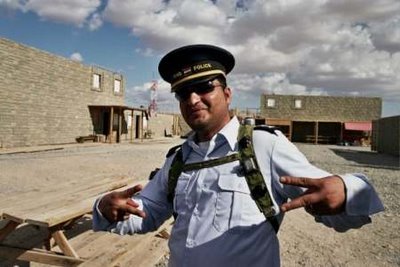

Gerber and Moss’ backgrounds in fiction and politics respectively are put to excellent use in their first film as co-directors, Full Battle Rattle. The documentary is a fascinating examination of the U.S. Army’s National Training Center in the middle of the Mojave desert, where replica Iraqi villages – populated with real Iraqi expats and U.S. soldiers playing Iraqi insurgents – have been constructed to create simulated training scenarios to give troops bound for the Gulf what is essentially a dress rehearsal for war. Following the experiences of both the soldiers in training and the “villagers” and “insurgents,” Moss and Gerber draw out the surreal ridiculousness of the simulation, which plays out like a cross between a soap opera and a murder mystery weekend. However, despite its dark and often hilarious humor, Full Battle Rattle never loses sight of the fact that its subject is ultimately deadly serious, that every fake death in the simulation could be a real death on the battlefield, that the fake Iraq where the refugee role players spend their time is now more of a home to them than their own country.

Filmmaker spoke to Gerber and Moss about occupying this strange alternate reality, the war films that inspired them, and making films with dead people.

Filmmaker: This is the first time that you two have worked together. Did you have a friendship prior to Full Battle Rattle or was it the project that brought you together?

Moss: We had an existing friendship. Tony had briefly been a television executive at AMC and commissioned a documentary that I directed about Republicans in Hollywood, so we worked together creatively on that project. It was a great relationship and as Tony is first and foremost a filmmaker we had talked about working together on a project. About two and a half years ago we sat down, this idea came up and that was how our directing partnership was born.

Filmmaker: How did you first come across the story of these fake Iraqi villages?

Moss: When we talked about collaborating, there were a couple of news articles about the simulation. Up until that point, it had really been secret and the army had gradually allowed some people to come in and take a look. It was almost like journalists on a safari, where they would escort them around. It seemed too strange to be real to us. Around the same time, the news from Iraq was so awful, the war was going so terribly and it had become very overwhelming, and I think both of us were looking for a way to engage with the war as filmmakers. This struck us as a total strange and surreal story and one that could potentially make a fascinating documentary.

Filmmaker: Did you have a clear idea beforehand of what the simulation would be like and how you wanted to capture it in the film?

Gerber: I think we had a very, very strong gut reaction and instinct that the life around the periphery of this training exercise would be damn fascinating. You have U.S. soldiers bound for Iraq, many of them never out of their own country before in their lives. You have U.S. soldiers who’ve been to Iraq and are now back playing the part of insurgents. And then you have Iraqis in various roles as civilians on battlefields. So what happens when the curtain drops? What happens around the fringes of this training protocol when you have U.S. and Iraqis living side by side in the middle of the California desert? [They’re] playing volley ball together, barbecuing, negotiating the life of a village. There’s this ersatz village that exists that was created for the purpose of training soldiers, but you have a real village, a real community that grows organically out of the mere fact that you’ve dropped these disparate people off in the middle of the desert.

Moss: We knew they were fighting the war in simulation and the attraction of that was the opportunity to capture this war from both sides – the insurgency and the American soldiers. We didn’t have a lot of money and we didn’t have a big crew, but we both shoot and we both work independently, so could split up and embed respectively, me in the village of Medina Wasl and Tony with the 4th Brigade.

Filmmaker: How long did it take to get permission to make the film? Presumably such a thorough portrait of their training methods was not quick to get approved.

Gerber: Yeah, it was really a mission impossible getting the greenlight, but through persistence and by hook and by crook we managed. Once we got there, we found that what we were doing so was so out of the ordinary – at least in terms of what the public affairs officer at the National Training Center was used to – that we flew below the radar. I think eventually they forgot about us.

Filmmaker: So you went and lived on the base for three weeks.

Moss: I lived in the village of Medina Wasl and Tony lived on the forward operating base [F.O.B.] of the Army Brigade. And we should distinguish between the Army Base and the F.O.B.

Gerber: Yeah, if you’ve been to army bases you’ll know that they’re little communities, little cities with their own Taco Bell, multiplex movie theater and shopping mall, but then 10, 20 kilometers outside of there is the F.O.B.

Moss: The city of Fort Irwin is about 20,000 people in the middle of the Mojave that rises from the sand like a…

Gerber: …strip mall, really, [laughs] as you approach it from the desert. But then outside of that you have a staging area known as “The Dustbowl,” which is the representation of Kuwait. So when the simulation begins, the brigade sorts out all of their gear and equipment in the Dustbowl and then prepare to travel out to “The Box,” hostile territory.

Moss: The Box is Iraq, a 1000-square-mile simulation of one entire Iraqi province with [a number of] villages. When we started the film there were six villages, and there are now 19.

Filmmaker: How easy was it for you to embed? And how long did you have to familiarize yourself with both groups before you started filming?

Gerber: The nature of the work that we do is that they get to know us as the guy with the camera, so you get to know them as you’re shooting. It serves two purposes: determining who are the compelling characters who will work on screen, but also getting folks accustomed to how it is that we work.

Moss: It was very difficult, to be honest, to [just] airdrop in. Both the Iraqi village and the brigade are very insular communities, and there was a lot of suspicion. We didn’t have the lead time to spend with these folks before we could start filming, so I found that very tough and frustrating.

Filmmaker: Which one of you found it more challenging to assimilate into the respective communities?

Gerber: We had the opportunity to go back and to pick up interviews with the Iraqis in the village after the brigade had left for Iraq, so I had the privilege of seeing that world from Jesse’s perspective. It was very different, and in a lot of ways the level of anxiety was different. The levels of anxiety were extremely high up on the operating base, and it was night and day.

Moss: Tony, you had three thousand soldiers to choose from, but I had a much smaller community, Iraqis and soldiers to choose from. I had cultural challenges and you had the sheer enormity of the cast you were working with…

Gerber: …plus a cultural challenge. The military is a culture unto itself, and it was a complete and total immersion. In some ways, living in the neighborhood I live in in Brooklyn, I had more in common with the Iraqis than I did with a specialist from rural Arkansas.

Filmmaker: It struck me that the Iraqi village was maybe easier to film because they were performing anyway much of the time, and thus used to constant scrutiny.

Moss: They’re actors, they’re used to taking direction in some way, but culturally there was a great deal of suspicion. For the longest time, they thought that Tony and I were CIA operatives, and for some of them who still had family in Iraq there were very real concerns about privacy and the risks that they might expose their families to if their images were presented in our film. They were happy to show us what it was to be a role player in a simulation, but they weren’t necessarily willing to talk about their family in Iraq and the fear they felt or how they’re perceived in their communities back home because of the work they do.

Filmmaker: There a curious irony that the Iraqis are working for the American army, and there are U.S. soldiers playing insurgents who are gleefully “killing” huge numbers of their fellow soldiers, both engaged in a betrayal of sorts.

Moss: I found that double betrayal quite fascinating, Iraqis who are perceived by some as turning on their country and collaborating with the army. And for Sergeant Greene and his buddies in the insurgents, there’s a great deal of glee in “blowing shit up” and killing their American comrades. [laughs] In fact, after Greene led that night mission in which they “killed” many American soldiers, [he and his men] were actually awarded a medal. We weren’t allowed to film that for some reason, but I just found it perverse.

Filmmaker:When I initially heard about the movie’s premise, I didn’t initially think it would be so funny or irony-laden. Was it always your plan to focus so much on the comic complexity of the situation?

Gerber: Yeah, absolutely. I don’t think either of us are interested in literal, one-dimensional work, we’re interested in the many layers of this place and interested in it as a prism through which to view the war. Early on, we discussed this as a multiple character film that’s ultimately about a community. For us, many of the references early on were the films of Robert Altman, because he makes films about communities exceptionally well, and there’s a beautiful, lyrical sense of irony that was also important to us. And we found it there in abundance.

Filmmaker: The Altman film most comparable here is M*A*S*H. Did you have that or any other specific touchstones in mind while making this?

Moss: The war films that I have responded have taken a sideways look at war or inverted our expectations. Recently, I think Three Kings is an enduring work of the first Gulf War, a combination of realism and humor and gritty aspects. Peter Davis’ Hearts and Minds is an extraordinary documentary about Vietnam that broke formal ground in the way it was constructed.

Filmmaker: The world of the simulation becomes almost more real than the world outside for the role players. When you were shooting, did you ever forget that this was all fake?

Gerber: From the perspective of Lieutenant-Colonel McLaughlin and his battalion, it didn’t feel fake and in many ways it wasn’t. The analogy is really that of scrimmaging in football: it’s hot as hell, you’re sweating, you’re banged up, someone smashes their helmet into your gut and it hurts, it hurts as much as it does in a real game. And so I think for those guys, it does become real.

Moss: With the brigade, they never turned off. But in Medina Wasl, even though the simulation is 24/7, Sergeant Greene and his buddies in the insurgents would come home after a raid and fire up the barbecue and have some down time. That was never true with Colonel McLaughlin. There was no down time. Mistakes were and are very real to them in a way that they were not to the people of Medina Wasl.

Filmmaker: It’s very dispiriting to see how incapable the troops are of dealing with even the training situation, so were you similarly depressed while filming them?

Gerber: When Colonel McLaughlin admitted to failure, which is an extremely poignant moment in our movie, it was one of those times as a filmmaker when I felt almost embarrassed shooting it, because it’s so naked. And I was shocked to discover that there are simulated memorials for fallen soldiers. As a notion, it’s a touch absurd and has great potential for comedy, so I thought this had to be documented. But you get in that room and you hear the bagpipes and you see grown men weeping over a dead fictional guy – it’s an extremely surreal experience, and ultimately very, very emotional.

Moss: I’ll say from my perspective, the first time I saw Sergeant Ramsay with his mechanical robotic mannequins, the bodyparts, the blood and the makeup, I thought “This is the craziest thing I’ve seen. This is truly horrifying in a way that the war has never been made horrifying to me.” Just seeing the length to which they had gone in the simulation to reproduce that experience, where they have severed limbs, spurting blood and these mannequins with pre-programmed voices calling for help, it was bizarre and blackly fun but also really stomach-turning and quite awful. It made the war real in a disarming way that we hoped the story would for our viewers. These are taboo images – you don’t see injured American soldiers, you don’t see dead American soldiers – and there were ways that we could get into the war through these funhouse mirror reflections.

Filmmaker: What’s the smartest decision you ever made?

Moss: Some of the better decisions I’ve made have been almost unconscious decisions. I used to work many years ago, in a previous incarnation, in politics. I was not happy and I sort of threw myself off this cliff and came to New York with a dollar in my pocket and went to work for a filmmaker. Looking back on that decision, I can’t understand it in rational terms – because I had a good-paying job and didn’t know anybody in New York – but I just felt like I needed to do something and this was it.

Filmmaker: If you had an unlimited budget and could cast whoever you wanted (alive or dead), what film would you make?

Gerber: I’m sort of a romantic and I think I would do some spin on Romeo and Juliet, and I would cast Heath Ledger and that woman who was a U.N. ambassador and was in Sabrina… Audrey Hepburn. Both dead, unfortunately.

Filmmaker: Finally, if you could hand out an Oscar to someone who’s never won, who would you give it to?

Gerber: I got one: Hal Ashby.

Moss: That’s what I was thinking, actually.

Gerber: Another touchstone for us was Coming Home. We talked about that film a lot. The tone of it, and it’s grounded lyricism is so beautiful.