Back to selection

Back to selection

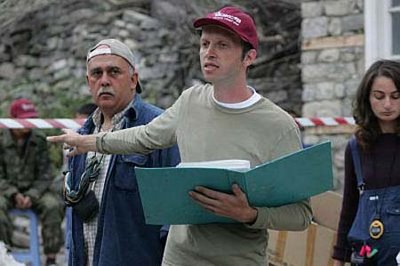

Veit Helmer, Absurdistan

German writer-director Veit Helmer is a true oddity, a creative mind whose films might well have been unearthed from a time capsule buried during the era of silent comedy. Born in Hanover in 1968, Helmer spent much of his childhood watching Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd and by the age of 14 had already made his first film. He studied at Munich’s School of Television and Film, and made quirky shorts throughout his time there, such as the highly inventive Surprise! (1995). When Wim Wenders, a professor of his, decided to make a film based on one of his students’ screenplays, he chose Helmer’s submission. The resulting film, A Trick of the Light, playfully combined documentary and fiction and displayed the retro visual style which has become Helmer’s trademark. In 1999, Helmer made his feature debut with Tuvalu, a festival hit about a crumbling bathhouse which was almost dialogue-free, was shot in color and black-and white, and tonally recalled both vintage silent comedies and the films of Jeunet and Caro. In 2003, Helmer followed it up with the much more conventional Gate to Heaven, a romantic comedy about illegal immigrants in Germany set in the present day.

Helmer admits that Gate to Heaven was an ill-advised attempt to prove he could make a “normal” film, but fortunately with his third feature he is well and truly back in his comfort zone. Inspired by a newspaper story Helmer read some years ago, Absurdistan is about a remote village where the women go on strike and refuse to have sex with their husbands until the pipe providing water to the village is repaired. Set against this Lysistrata-esque battle of the sexes is the central narrative, the story of Aya (Kristyna Malérová) and Temelko (Max Mauff), young lovers whose predestined union is threatened by the village rift. As with Tuvalu, here Helmer opts for visual storytelling over dialogue and uses both old-fashioned visual styling and silent comic routines. Though the story is straightforward, Helmer tells it with charm, imagination and gentle humor, creating a sweet and, yes, absurdist comedy that blends old and new in just the right way.

Filmmaker spoke to Helmer about his retro tastes, the international nature of his filmmaking, and the dangers of not recognizing Glenn Close.

Filmmaker: When and how did you get the idea for Absurdistan?

Helmer: I read a newspaper clip in 2001 about a village in Turkey where the women actually went on strike, saying to their husbands that if they didn’t fix the water pipe they would not allow them to enter the bedroom. When I read that, I immediately knew not only that I was going to make a film about it but also I knew very much what the film should be about. It would be able a couple against the village, rather than men against women or women against men.

Filmmaker: Did you immediately also have a clear visual idea of the film in your head?

Helmer: I think so, but let’s say the tone or the mood. I let myself be influenced a lot by locations and for this film it took me two years to find the appropriate village. I hoped very much that the village where the actual strike took place could be the village for shooting the film, but that was completely disappointing and also all other villages in Turkey which I visited could not become the right setting for the film, for different reasons. At the beginning, I felt it was really simple: I just need a little village in the desert. But the more I was looking, it turned out I had really specific ideas: that the houses should be very close to each other, that there should be a kind of urbanity in the village (it’s not a village of peasants). I wanted some shops, I wanted that people should have social places where they could meet each other. I went around all countries in southern Europe, the Mediterranean, the Caucasus and Central Asia until people then recommended I go to Azerbaijan, where I found two villages which I combined to make that place.

Filmmaker: How did you progress once you’d found your locations?

Helmer: I went there with my writer, my art director and my cameraman and we were then enriching the screenplay with more places that we saw. We eliminated some stuff from the screenplay that was weaker than places that we actually found in the town. It was a little small town that we found, but it was a rich village and had a 4,000-year-old history. We made a documentary about the making of the film and you can see some of the things I had to do to make the film happen, because that village really was nowhere. Also Azerbaijan is also not a country where they know how to make movies, so what I did after all the location scouting is I trained the film students in the capital of Baku to work with film, because all they do at the moment is to work on video. So two years before I started making the film, I started educating assistants for my crew. I could have brought all my crew from outside, but as the subject was very sensitive for a Muslim country I needed local help to make the villagers trust me that what I was doing was not a porn movie – and that was what they had always suspected! It was really funny because finally I needed also some nude scenes and then that was always a difficult communication: “Yes, we’re doing nude scenes but it is not a porn movie.” It’s very difficult for people who don’t know Western cinema or independent cinema.

Filmmaker: Location seems to really drive the inspiration for your work, whether it’s the house in Surprise!, the bathhouse in Tuvalu, the airport in Gate of Heaven or now the village in Absurdistan.

Helmer: I would say that I really tend to conceptualize as much as possible, that I really go with some kind of preconceived vision, but then, on the other hand, I totally believe in the moment of shooting. I think that a director should let things happen so when the day of shooting comes and the actors and the costumes come to the locations, I really don’t try to push that everybody delivers my two-dimensional prefabricated thinking. I want life to surprise me. I’m not a director who tells the actors how to move. I take a very long time to choose the people I’m collaborating with, and then I tend to trust them. For instance, actors usually know better what their characters should do. So even if my films don’t follow the laws of realism, let’s say, I still believe in the credibility of human behavior. I’ve also started to do documentaries, which really helped me to be more open to incorporate life as it happens in my life.

Filmmaker: You briefly mentioned cultural differences before, but what was the experience like of shooting in Azerbaijan?

Helmer: Azerbaijan is a Muslim country, less strict than Iran but maybe more like Turkey. I prepared myself very well, I wrote in the contracts of all the people coming from other countries that the men shouldn’t look at the girls in the village, the women should dress appropriately so not to [cause offense]. When you’ve found such a nice place after two years, you don’t want to lose it in the middle of shooting! [laughs] So I was really trying to take a lot of care, like a teacher who goes with his class to some place and asks everybody to behave really nice. I had to build the hotel, I had to set up a complete infrastructure: we had to import the camera, we had to bring our lights from Germany, a generator from Georgia. It was a very difficult logistical task. On Tuvalu, I went to eight different countries to look for actors, because there was no dialogue, and it was really nice. On Gate to Heaven, I had to do it [again] because it’s about immigrants from different countries, and I went to 12 countries. With Absurdistan, I really took it to the top and really wanted to find actors in every corner of the world and went to 28 countries, which was another two-year journey, and finally I chose actors from 16 countries. So we were this really Babylonic team which came there. It wasn’t like German and Azerbaijani people, it was people from everywhere. The crew already had to get along with each other, and then it was about this multicultural crew with the villagers.

Filmmaker: Were there communication problems with such a broadly international group of people?

Helmer: Because I did the casting myself everywhere, I knew that the people I was going to bring there were really going to do this film, they wouldn’t ask for four star hotels and that they would work for a fraction of their usual salary. These people who came with me did it for other purposes, partly because it was a creative challenge but most people were fascinated to go to country that they had never even heard of before. Some people created personal websites about that journey, there were 17 relationships, three couples married after the shooting and I’m attending festivals all the time and have to go because babies get baptized. We have real community of people, and the real people of Absurdistan are now in the making!

Filmmaker: You have a very distinctive style, as your films have minimal dialogue and have a lot in common with silent comedies. Why do you develop that approach in your filmmaking?

Helmer: I think I like to take the best from silent filmmaking, as the visual language before sound came was much more elaborate than most of what we see nowadays in the cinema. Films were about visual storytelling at that time but I think I can combine the best of both because I like to work with sound. For me, sound has the same importance but I don’t like to use sound just as dialogue and a little ambient sound and music in the background. Once you don’t use dialogue, it means that you have an important task to fill that void with something which does not feel empty. I know how to cut the movie (anybody could cut my films), but to make the sound design is much more important so I feel misunderstood if people say it’s a silent film just because there’s no dialogue. I know you’re not saying that, but people do say that and I always read it in festival catalogues. My sound designer is on the verge of getting a pump gun after working a year [on the film] and then reading that Veit Helmer made this silent movie. I like to play also with references to other films. When I was small, I saw lots of films by Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, but then when I was getting older I watched all the Nouvelle Vague, a lot of independent American films and I’m trying to see as much as film as I can. I love to watch movies and I’ve tried to see cinema as it evolves from all countries. I very much like simple storytelling from Iran and I like complicated, complex dramaturgies as well. I don’t only like films that are similar to my films.

Filmmaker: You lecture in many different countries and your films always have a real international flavor. Do you feel more global or German as a filmmaker?

Helmer: Looking out of my window, I can see Berlin around me. When I go to travel with my film, yes I’m presented as a German filmmaker but for me it’s already hard if you ask me what German film is today. I’m not sure if German films are so fantastic, but I can guarantee that they’re very diverse and in this big diversity is also me. One of my best friends, my neighbor Bakhtyar Khudojnazarov who made Luna Papa, he’s from Tajikistan. That’s the good thing about Berlin and Germany today: we are really becoming very cosmopolitan again, maybe what New York used to be. Traveling gives me inspiration and it gives me fulfilment and I travel five times making a film: I travel to find locations, to work with writers, to find actors, to shoot, and then I go to festivals. And, in between, I teach because for me there is no way to enter a country deeper than to work with a dozen enthusiastic film students for a week and make a short film with them. I feel bored sitting on a beach – I cannot sunbathe longer than five minutes or I get bored.

Filmmaker: Can you tell me about the experience of working with Wim Wenders on A Trick of the Light? The film seems to show the first signs of your cinematic style.

Helmer: Yes, I hope Wim Wenders gets asked sometimes how big was my influence on him, because in every interview I have to say what his influence was on me. I think he had a big influence in how he produces and keeps control of his films since Hammett. That was one lesson, and the other was how he keeps control by stimulating a crew, by given them responsibility and trusting them. I also learned from him how to teach. He taught us very nicely. He came to Munich Film School and said “Let’s make a movie, now write a screenplay,” so we wrote screenplays. I was lucky he chose mine, and now I do things the same way when I go to all these cities and do these workshops. I think, “Let’s get out of the classroom and shoot a film.” That’s what I learned from him and I owe him a lot.

Filmmaker: When was the last time you cried in a film, and which film was it?

Helmer: I think it was Katyn, the Andrzej Wajda film, which I saw at the Chicago Film Festival in October last year.

Filmmaker: When did you last do it for the money not the love?

Helmer: That’s 18 years ago. I had to finance my study in Munich and I did some horrible TV work. I felt like a prostitute, but I think I was happy from that moment on. I even did lots of commercials and earned a lot of money, but I wouldn’t say that I did it for the money – I really enjoyed doing them. But this TV work, I really have to say that it’s really like a black spot on my conscience.

Filmmaker: Finally, what’s the biggest compliment you’ve ever received?

Helmer: I’ve received very many beautiful compliments – honors and awards and audiences saying very nice things – but the funniest thing was last year at Sundance. A tiny woman came up to me followed by this big tall man and she said she loved my movie. I didn’t recognize her, but it turned out it was Glenn Close. She was running after me on Main Street in Sundance, and the guy behind her – this bodyguard, this gorilla – wanted to kill me when I asked her who she was. [laughs]