Back to selection

Back to selection

Things That Seem Real, Part 3 : Catfish And Fakery

Editor’s Note: Part one of this essay, “Things That Seem Real: A Three-Part Essay on Catfish and Other Movies,” appeared Tuesday on the site and can be read here. Part Two appeared yesterday and can be read here. These essays contain major spoilers regarding the film Catfish.

Catfish and Fakery.

Catfish has some major truth-problems. Major. Like, plot holes big enough to drive a truck through. The stirrings of suspicion began instantly after its Sundance 2010 premiere. On January 30th, reporting from Sundance, Indiewire’s Bryce Renninger wrote that “Over the week since its premiere, though, many critics and audience members doubted the film’s truth claims.”

Catfish has some major truth-problems. Major. Like, plot holes big enough to drive a truck through. The stirrings of suspicion began instantly after its Sundance 2010 premiere. On January 30th, reporting from Sundance, Indiewire’s Bryce Renninger wrote that “Over the week since its premiere, though, many critics and audience members doubted the film’s truth claims.”

Eric Kohn, writing for The Wrap a day earlier, questioned the filmmakers’ presence every step of the way: “The camera seems almost too ubiquitous, capturing every major plot development in the incredulous story. One key scene, for example, involves Nev’s sudden discovery that his online girlfriend has sent him a song under the assumption that it’s a recording of her own voice, when in fact it has been nabbed from YouTube. This red flag sets up the larger discovery of the woman’s identity, and the whole thing conveniently takes place on tape. Did the filmmakers really get that lucky?”

Kyle Buchanan wrote a more blistering piece for MovieLine, published on the same day. “[Co-director Ariel Schulman’s] claims of innocence are hard to believe,” Buchanan wrote. “Despite the fact that there were meticulously faked Facebook pages for Abby, Megan, and Angela, a simple Google search of the Pierces blows holes in their story (especially the notion that Abby’s painting made her a local celebrity), and you’re telling me that a pair of young filmmakers documenting said story would never think to Google their mysterious subjects over a span of several months?”

Kyle Buchanan wrote a more blistering piece for MovieLine, published on the same day. “[Co-director Ariel Schulman’s] claims of innocence are hard to believe,” Buchanan wrote. “Despite the fact that there were meticulously faked Facebook pages for Abby, Megan, and Angela, a simple Google search of the Pierces blows holes in their story (especially the notion that Abby’s painting made her a local celebrity), and you’re telling me that a pair of young filmmakers documenting said story would never think to Google their mysterious subjects over a span of several months?”

They all make fair points. There are any number of red flags that get raised if you try to consider Catfish a completely un-manipulated documentary. Some of them can be rationalized (Kohn’s grievance about the ubiquitous camera — if Joost and Schulman were making a doc about Nev’s relationship with Megan/Abby, it would make sense that they would be filming him during a significant amount of his interactions with them), but some things are certainly questionable (Nev just so happens to discover the faked cover songs and the fact that Abby’s art gallery is actually an abandoned building while they are in Colorado, much closer to Michigan than New York?), and some are downright fishy.

As Buchanan points out, Nev, Ariel and Henry are savvy, plugged-in New Yorkers who could probably spot a ruse like this one from a mile away. Or at the very least, once they came into phone or text message contact with it. Nev is a good-looking 24-year-old guy who lives in New York and supports himself as a photographer. He has hip filmmaker friends, he’s charming, and surely he has an active social life. Are his romantic options really such that he would have the inclination and/or the time to get involved with some girl from Michigan who he’s never met? Dubious. And is it realistic to assume that he would carry on an eight-month internet-only relationship with Megan without ever suggesting they meet up, until a hole is found in her story? Highly dubious. Additionally, while Nev has much e-correspondence with nine-year-old Abby, he talks to her exactly once on the phone, for just a few moments, and she seems almost completely unaware of who he is. Yet the three guys seem completely incapable of piecing together what’s going on until after they meet Angela in person. Yet Nev, all along up until that point, seems to completely believe in Megan’s highly suspect existence.

Catfish seems to be peppered with lies, with total, utter fakery. Surely it’s something that will be hotly debated throughout the cinephile blogosphere in the wake of the film’s release. And yet, the film’s fakery is utterly inconsequential. Anyone who debates the merits or veracity of Catfish’s truth-claims is missing the point; not just about Catfish, but about the nature of art itself.

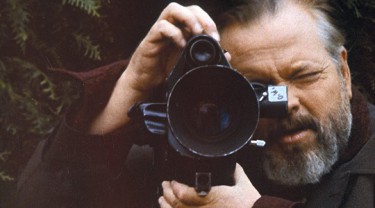

“The important distinction to make when you’re talking about the genuine quality of a painting is not so much whether it’s a real painting or a fake,” said the writer Clifford Irving. “It’s whether it’s a good fake or a bad fake.” The remark is made in F For Fake, Orson Welles’ dizzyingly Derridean masterpiece that shatters plenty of binary oppositions we’ve come to hold dear in our understanding of art. In one sequence, Oja Kodar parades down a street in Ibiza as various men eye her with various levels of indiscretion. The men are filmed with a telephoto lens, unaware of the camera’s presence. The scenario, Welles explains, is artificial — the footage is from a film he was making on “the sport of girl-watching.” Oja, seemingly just a woman on the street, is actually an actress there for a purpose — to get the sequence in the can; the gentlemen watching her, responding genuinely, are in fact unwitting actors in the contrived reality Kodar has created.

“The important distinction to make when you’re talking about the genuine quality of a painting is not so much whether it’s a real painting or a fake,” said the writer Clifford Irving. “It’s whether it’s a good fake or a bad fake.” The remark is made in F For Fake, Orson Welles’ dizzyingly Derridean masterpiece that shatters plenty of binary oppositions we’ve come to hold dear in our understanding of art. In one sequence, Oja Kodar parades down a street in Ibiza as various men eye her with various levels of indiscretion. The men are filmed with a telephoto lens, unaware of the camera’s presence. The scenario, Welles explains, is artificial — the footage is from a film he was making on “the sport of girl-watching.” Oja, seemingly just a woman on the street, is actually an actress there for a purpose — to get the sequence in the can; the gentlemen watching her, responding genuinely, are in fact unwitting actors in the contrived reality Kodar has created.

So what is this sequence? Real? Fake? In effect, it rests somewhere in the grey zone between the two. Its “realness” is not important — what matters about the sequence is whether it will be effective when Welles uses it in his girl-watching film. Irving said that what matters is whether it’s “a good fake or a bad fake,” but perhaps he would have done better to phrase that as “a good painting or a bad painting.” Throughout F For Fake, Welles returns continually to the idea of resonance and beauty in art, unhinged from originating context, to advocate on behalf of those who produce works under false auspices. The film’s two subjects are Irving, who wrote the fake Howard Hughes biography which Hughes had supposedly authorized, and Elmyr de Hory, an infamous art forger who claimed to have been wildly successful in selling fakes to galleries around the world. While plenty criticized de Hory for his trade, and reviled Irving for the Hughes stunt, Welles comes across as being terribly charmed by it all; he suggests that an artwork’s lack of authenticity does not preclude it from possessing artistic merit. (And of course, who could deny the talent of a 23-year-old radio actor convincing housewives America was being invaded by Martians?) Welles goes on to argue, in one of the film’s more cine-essay passages, that an artwork’s “authenticity” is a paper tiger, a trope created amidst the emergence of “experts,” who are the only people authorized to inform the public if a work is of value or not.

In the film’s climactic dialogue, a restaging of a confrontation between Pablo Picasso and Kodar’s grandfather, who was an even greater art forger than de Hory (and far less well known), Welles-as-the-grandfather defends himself from Picasso’s critique that he has no integrity, no honor, no legitimacy as an artist. “Like you, I am unique,” Welles responds. “You’ve seen my big Cezanne at the Metropolitan? Is that just a forgery, my friend? Is it not, also, a painting?” A bit later, Welles’ last line of dialogue as the (dying) grandfather is: “Before I die, I need to believe something. I must believe that art, itself, is real.” Soon thereafter, we learn the truth — that Oja’s grandfather is a made-up character, that none of what we have just seen occurred — yet the impact of what has been communicated is not nullified or dulled by this omission of fraud. “My job was to try to make it real, not that reality has anything to do with it,” Welles says of the con. “Reality is the toothbrush waiting for you at home. It’s your bus ticket. It’s the grave…What we professional liars hope to serve is truth. The pompous word for that is art. For, as Picasso once said, ‘art is the lie that reveals the truth.’”

The writer Chris Hedges once told me that the difference between journalism and art was that journalism was concerned with facts, but not the truth, while art was concerned with truth, but not the facts. What could the facts have been surrounding the making of Catfish? Do they matter? And if they do, do they have any bearing on the merit of the film itself, what we watch onscreen for an hour and a half? Catfish exposes plenty of truths about how we interact with the digital world; what difference do the methods by which the film came about make? Our obsession with this sort of thing comes not from any sense of critical inquiry, but from the same impulses for trivial tidbits and behind-the-scenes facts that make us wonder if stars X and Y were fighting on the set of that great romance they made.

It is too tempting, however, to not go at least a little bit down the rabbit hole, to indulge in one final theory. Let us suppose that Catfish is, in fact, a hybrid of fact and fiction. That it went down something like this: Nev highly, highly exaggerated his interest in Megan for the sake of the story. Perhaps he was never interested in her at all, or lost interest as soon as he began to get inklings that she wasn’t who she claimed to be. Nev, Ariel and Henry all had a feeling that something wasn’t right with the picture well before they discovered the MP3 — in fact, perhaps they engineered their trip to Colorado to coincide with a time where they would push to find concrete evidence of things not adding up. Regardless, assume Nev’s interest in Megan was contrived, a staged emotion produced in order to keep the story flowing.

It is too tempting, however, to not go at least a little bit down the rabbit hole, to indulge in one final theory. Let us suppose that Catfish is, in fact, a hybrid of fact and fiction. That it went down something like this: Nev highly, highly exaggerated his interest in Megan for the sake of the story. Perhaps he was never interested in her at all, or lost interest as soon as he began to get inklings that she wasn’t who she claimed to be. Nev, Ariel and Henry all had a feeling that something wasn’t right with the picture well before they discovered the MP3 — in fact, perhaps they engineered their trip to Colorado to coincide with a time where they would push to find concrete evidence of things not adding up. Regardless, assume Nev’s interest in Megan was contrived, a staged emotion produced in order to keep the story flowing.

Even if this is the case, does it not still work? Is it not, in some bizarre way, in keeping with the entire project here? Catfish is a film about deception (of ourselves as well as others) and fantasy in a digital era — an era that finds us continually modifying, editing and reshaping the truth to find optimal results. The filmmakers’ fakery, then, is yet another layer of distortion, another instance of the virtual world (the film’s narrative) taking precedence over the real world. In fact, it’s about as literal as that takeover can become: Nev literally changes the coordinates of his own life, in an enormous fashion, for the sake of the digital document that is the film.

All this is to say that if you do have a problem with Catfish’s truth-claims, hopefully you won’t allow them to cloud your judgment of the film itself. After all, every documentary is a work of fiction, of fakery, to a certain extent. Choosing to edit out moments that occurred within the framework of the story, utilizing camera angles that obscure certain objects or subjects’ viewpoints, going with talking head X rather than talking head Y; making a documentary requires an enormous amount of editorial choices that impose themselves upon the “truthfulness” of the work, and what emerges is less a slice of true, untarnished Reality than we’d like to believe. But that’s okay, because art isn’t about presenting “real life” as it is — that would be no fun. “Real life” is far too awkward and messy, unpredictable and absurd, to be the makings of good art; it’s filled with non sequiturs and deus ex machinas and all kinds of “unearned” resolutions. Art is about presenting truth in a clearer fashion than real life could ever afford us. It’s an act of communication that goes outside of the bounds of the usual (in other words, that which seems “realistic”) in order to express the unspoken truths that run as undercurrents to our lives. Those truths, the profound ones, rarely get aired out loud, because they’re so prevalent that they’ve become invisible to us. Art’s goal is to make them visible, by rendering them in their extreme forms. That’s what Catfish does. Is the film real? Well, let’s leave it at this: art is realer than reality.

Zachary Wigon is a New York-based screenwriter and film critic. Since graduating from NYU’s film school in 2008, he has contributed writing on film to The L Magazine, The Onion A/V Club, NYLON magazine and The House Next Door, amongst other outlets. His first feature screenplay, For Your Entertainment, is currently in pre-production.