Back to selection

Back to selection

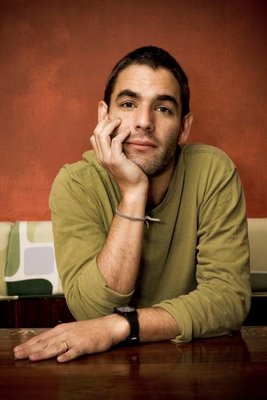

Fernando Eimbcke, Lake Tahoe

You only have to look at the work of a director like Fernando Eimbcke to see that there is a lot more to get excited about in Mexican cinema than just the so-called “Three Amigos,” Guillermo del Toro, Alejandro González Iñárritu & Alfonso Cuarón. Born in Mexico City in 1970, Eimbcke studied film direction at the University Centre of Cinematographic Studies at UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico). During his time there, he made a handful of shorts, including the fiction films Sorry for the Inconvenience and Excuse Me? (both 1994) and two non-fiction titles, Reaching a Star (1993) and Not everything is Permanent (1996), the latter of which was nominated for Best Documentary Short at the Ariels, the Mexican Academy Awards. Following his graduation, he began directing music videos, as well as more shorts, such as Weightwatch (2002) and The Look of Love (2003). In 2004, he co-wrote and directed his feature debut, Duck Season, a black-and-white comedy drama about two teenage boys left alone for the day who must entertain themselves after the power cuts out. The movie premiered at Cannes in the Critics Week sidebar, was programmed at numerous film festivals worldwide, and won no less than 11 Ariels, including Best Film, Best Director and Best Screenplay.

With his sophomore effort, Lake Tahoe, Eimbcke reunites with his co-writer on Duck Season, as well as one of the lead actors from that film, Diego Cataño, however in tone and texture the two films could not be more different. The movie begins with the downbeat Juan (Cataño) crashing his car into a lamppost – how and why this happened is unclear – and the film chronicles his efforts to get it back on the road. Helping him (or not) are a distrustful old man (Hector Herrera), a kung-fu obsessed mechanic (Juan Carlos Lara II), and the pretty girl who works with him in the repair shop (Daniela Valentine). As Lake Tahoe progresses, we become aware that driving the minimal narrative of Juan’s quest is a much more profound event, hinted at from the very start by Eimbcke’s empty and quietly mournful shots of the movie’s deserted town. A slow, ethereal piece of filmmaking, Lake Tahoe uses cinematic means – its expansive 35mm frame and frequent cuts to black – to convey a pervasive sense of loss and absence. Occupying a space between the real and the absurdly surreal, Eimbcke’s movie pointedly downplays its emotional aspects, keeping them as subtext until its poignant climax.

Filmmaker interviewed Eimbcke over email and asked him about the personal nature of his new film, the influence of Jim Jarmusch on his work, and his first movie memories.

Filmmaker: How did you get the idea for the film? What was your initial inspiration?

Eimbcke: I crashed my family’s car a few months after the death of my father. I told this story to Paula Markovitch, the co-author of the script, who also lost her father and we began to construct the story. Both of us needed to tell this story. I’m the director of the film but the story is a Paula’s and Fernando’s personal story.

Filmmaker: What was your reason behind making the film so sparse and minimal?

Eimbcke: When I finish the script, the shooting, the editing, every process of the film, I like to think, “Can I make it more simple? Can I express what the character needs in one sentence? Or without dialogue?” I’m obsessed with the simplest way.

Filmmaker: The film uses many cuts to black, which is relatively unusual in contemporary films. Why were you drawn to use this approach?

Eimbcke: Cut to black is a transition tool but is also a narrative tool. In cinema when you put two images together you have a new meaning. It is the same with cuts to black. Following a scene or preceding a scene, a black frame is not anymore a black frame. There’s a lot of people who only see a black frame, an empty frame, I don’t.

Filmmaker: Stranger Than Paradise is probably the most famous film of recent times to use cuts to black as an editorial method. Was it a specific inspiration in this instance?

Eimbcke: Of course. When I saw Stranger Than Paradise I fell in love with the film. Something caught me. Maybe in the cuts to black I found that certain meaning I talked about in the previous answer.

Filmmaker: Duck Season was also a film which was compared to the work of Jim Jarmusch. Has he been a big influence on you?

Eimbcke: Yes, I fell in love with the simplicity and complexity of Jarmusch’s films, particularly with Stranger Than Paradise. Thanks to Jarmsuch and Kaurismäki, who also is a big influence, I discovered Ozu. And Ozu’s work influenced and will continue to influence a lot of filmmakers. Ozu is the Master.

Filmmaker: The film’s narrative is very linear, but all the relationships are broken up and staccato, stopping and then starting up again later. Can you talk about why it is like that.

Eimbcke: The character wants to escape. He spends all the story trying to avoid all possible relations, but at the same time he needs all those relations. I remember Paula Markovitch laughing about the idea of a frustrated road movie.

Filmmaker: The film feels very natural and spontaneous. Did you allow your actors to improvise?

Eimbcke: It depended on the scene. Sometimes I felt the scene needed improvisation and sometimes I didn’t.

Filmmaker: Both Duck Season and Lake Tahoe are about young people dealing with situations where things they take for granted (electrical power, a car) stop working. Was this a conscious exploration of similar territory?

Eimbcke: It wasn’t a conscious decision. What happened is that Paula and I enjoy a lot to work with simple and absurd situations.

Filmmaker: Both of your films are also about a world where parents are absent, most poignantly so in Lake Tahoe. Is this another theme that continues to interest you?

Eimbcke: Yes, I’m sure I’ll continue exploring the same theme but with different angles. If someday I make a love story, I’m sure the theme of parents’ absence will be there.

Filmmaker: Can you explain the significance of the film’s title? It reminded me a little of Chinatown.

Eimbcke: Juan’s brother spends all the film collecting memories. Some of them are real, some of them are fantasies. He needs to believe that all of them went to Lake Tahoe. At the end of the film when Juan returns to his home, he finally accepts the fact that his father died. When he says to his brother “We never went to Lake Tahoe” he’s saying “Our father is dead, that’s the reality”.

Filmmaker: Lake Tahoe is beautifully shot in 35mm. How important was it for you to shoot on film rather than digital? (Are you interested in shooting on digital in the future?)

Eimbcke: There’s one reason I want to shot in 35mm. It is beautiful. I’m sure one day I must shoot on digital, but I’ll be very sad looking at the image.

Filmmaker: Mexican cinema is going through a golden period at the moment. What do you think are the reasons for this happening?

Eimbcke: All the Mexican directors I admire the most have in common a profound love to cinema.

Filmmaker: Is there a sense of community among Mexican directors? Who of your contemporaries are you friends with and discuss your work with?

Eimbcke: Carlos Cuarón works very near my workplace so we talk a lot about our work, and I learned a lot from him. Alfonso Cuarón distributed Duck Season, read Lake Tahoe and saw the film in the editing room. I sent the work print of Lake Tahoe to Alejandro González Iñárritu and he gave me very good advice. I have a very good relationship with Rodrigo Plá, Gerardo Naranjo, Julián Hernández, etc. There’s a sense of community.

Filmmaker: What was the first film you ever saw?

Eimbcke: It was Laurel and Hardy’s short films on television.

Filmmaker: Should a director always take risks?

Eimbcke: Yes, always. Shooting with no risks is boring.

Filmmaker: What’s your best piece of advice for aspiring filmmakers?

Eimbcke: Don’t aspire, be.

Filmmaker: Finally, if the world ended tomorrow, what (if anything) would you be sad about that you hadn’t achieved?

Eimbcke: I would be very sad about not having shot the story I’m writing right now.