Back to selection

Back to selection

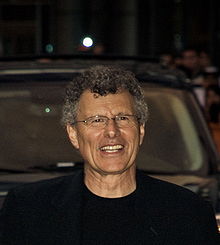

Jon Amiel, Creation

The first non-Canadian film to open the Toronto film festival in quite some time, Jon Amiel’s Creation seems to both embrace and shun the duties and limitations of the historical biopic. Paul Bettany stars as middle age naturalist Charles Darwin, well past his explorations on the HMS Beagle, who having settled into English country life with his children and wife Emma (Bettany’s real life spouse Jennifer Connelly), decides to finally tackle writing a book on his nascent theory of Evolution. Haunted by visions of his recently deceased daughter and the notion that he may permanently alter man’s conception of the divine, Darwin struggles through the completion of the text, sidetracked by tremors and sickliness. Containing a sophisticated and quietly engrossing look at a scientist’s relationship to faith and family, Creation is that rare story of an important historical figure that seems intimate.

The film marks a return to indie filmmaking for Amiel. The director of Tune in Tomorrow (1990) and Queen of Hearts (1989) cut his teeth in the 80’s directing the laudable British television mini-series The Singing Detective before a sustained run of star laden, Hollywood work in the 1990’s such as Summersby (1993), Copycat (1995) and Entrapment (1999). His most recent feature was 2003’s The Core.

Creation opens on Friday.

Filmmaker: You’ve made a historical biopic about Charles Darwin that in many ways resembles a horror film with its uses of nightmarish dreams and the haunting of a grown man by a dead child as a principle narrative device.

Amiel: Yes. When I approached this whole idea of making a film about Darwin, I started off with all the things I didn’t want to do. Didn’t want to make a biopic. Didn’t want to make a dramatic documentary. Didn’t really want to make a “period” film. Didn’t really want to make a reverential portrait of a great man. I’ve seen films like that and they’re dull. They don’t really belong on a feature film screen. They’re more the purview of documentaries, dramatized documentaries and the sort of thing you’d see on PBS.

What I discovered about Darwin excited me a great deal, much more than I ever expected. Reading about him, reading his letters to Emma and from Emma, his journals and the recollections of his children, this whole different human being emerged for me. He embodied many paradoxes. He was a great pillar of rational thought who was haunted by tremendously irrational fears, doubts and anxieties. He was married to a woman who was his best friend and yet with whom he held diametrically opposed ideas. He was writing a book that would change the world. The act of writing this so perturbed him that he became physically ill, vomiting, shaking, fainting. He had a number of other systems that we don’t go into in the film. All of these things and then he was dealing with the most difficult thing a parent can ever deal with, the loss of a totally beloved child.

So what I set out to do with [screenwriter] John Collee was to get inside the mind of this man to understand what it must feel like to be a naturalist who sees the young of various species parish on a daily basis and observes them dispassionately as a simple fact of life. You’re now looking a fledging baby rabbit being eaten, but now through the prism of having lost your own beloved child. You’re looking at a decaying, decomposing baby bird and thinking about your own child decomposing in her grave. What were the thoughts and ideas rushing through his mind when he was working on this book that made him physically ill. So the film and the visual sequences that you’re referring to are an attempt to get inside the mind of a great man. Some of the ways in which a great pillar of rational thought, The Origins of Species, may have come from processes that prove to be anything but rational at the time. We think of scientists as these cool, rational people in white coats dispassionately jotting ideas down, The fact is, weather you’re talking about the story of Francis Crick or Galileo or John [Forbes Nash Jr.] from a Beautiful Mind, the product of science might be a rational thought, but the process of science is for the individuals themselves is frequently anything but rational.

Those are the things we sought to explore in the film to escape from the tyranny of the BBC costume drama set in the beautiful rolling hills of Kent. [Laughs]

Filmmaker: So it was very early on that you and John Collee decided to focus on the writing of The Origin of Species as opposed to the controversy that it set off or Darwin’s travels on the Beagle.

Amiel: Feature films don’t do abstract ideas so well. It deals with them best when it embeds those ideas in character conflicts. I think any great film that’s produced any ideological change, weather it’s Inherit the Wind or Z or Salvador, any film that makes a controversial, world changing statement, they all succeed primarily because they are great drama first. They’re about people you care about. We started very much from that place with this film. We didn’t want to make a tract; we wanted to make a film that shows the science that conceals science and the art that conceals art. We wanted to embed Darwin’s ideas within the drama that was his daily life. A lot of those ideas are embedded in the dream sequences you mentioned for example, where you might have a young female Orangatang juxtaposed with images of his young child, who may also appear while poshing around the skeletonizing shed, killing pidgeons and analyzing there wing structures. So I believe a great deal of his thinking is there in the film.

As for the controversy, I really didn’t want to see those awful scenes set in oak paneled room with a bunch of guys in black frock coats and big side whiskers standing up and going “No! Outrageous! Shocking! Scandalous!” [Laughs]. It seemed unnecessary to do that. We made the choice very early on to focus on the family and the process of writing Origin to allow the fact that the book is still as controversial now as it was then to take care of its self in effect. In other words we end with this great, world changing masterpiece trundling off toward London precariously perched on the back of a cart-

Filmmaker: I kept hoping he’d made a copy.

Amiel: Yes, one does feel that and actually I believe he did. What I found so alluring about this world changing masterpiece trundling off on the back of a cart, was, oh my God, what if it had fallen off? How fragile a thing that was at that moment, slouching toward Bethlehem to be born.

Filmmaker: Did it make it any easier to craft the intimacies and painful conflicts of a married couple by having a pair of leads who themselves are married to each other?

Amiel: Working with this particular married couple definitely made it easier, yes. As well as having fifty years of camera experience between them, they were brave enough and smart enough and willing enough to explore painful, difficult aspects of themselves and their relationship in front of the camera. My job by and large was to get out of the way. It could have gone horribly wrong as a decision. If they had decided to gang up against me or if one of them comes in with a bad mood you know that the other one is going to come in with a bad mood, all of those things could have been pretty woeful, but they weren’t. Partly because of their sheer professionalism and experience, partly because they are incredibly courageous actors and they’re willing to go places that many actors are just scared to go to.

Filmmaker: When constructing the non-linear narrative in the editing room were there challenges you faced that you and John Collee hadn’t anticipated in the script?

Amiel: I was enormously strengthened and embolded in both conceiving of the film this way and cutting it by the experience I’d had with The Singing Detective, the mini-series for the BBC I did many years ago which told a story in a very similar way. The cutting room is the last and most important rewrite you do and in a non-linear film the editing presents really particular challenges. Scenes can go together in many different ways, both the material in the scene itself and the order in which the scenes are presented. We had hundreds of post it notes all over the editing room wall, each one with a scene on it. Blue ones for past sequences and red one for present tense sequences. The order changed many, many, many times, despite all the wonderful work that John Collee and I and done on the script. All kinds of things reveal themselves once you’ve shot a movie. We were working right up until the last minute, polishing the way in which the scenes were presented to make the story as clear and strong and rich as we possibly could. It was a tremendous challenge to get that right, to tell a story that was non-linear chronologically, but had a powerful, persuasive emotional trajectory in it that would carry and audience through the story.

Filmmaker: What’s the financing environment for a film like this right now where it’s increasingly difficult for specialty films to get much traction in the market place? I imagine the financing was contingent upon the participation of you’re two leads?

Amiel: You’re right that the film itself is an endangered species. It’s the kind of film that America almost didn’t get to see and in coming years may very well not get to see. Partly because films of this sort can’t find distribution, partly because they can no longer find financing. The way this came about was very simple for me. [Producer] Jeremy Thomas was the first person I pitched the idea too. I went to him with my research and a few key ideas John Collee and I had put together: that the spirit of his daughter would be a character in the story, that it would be non-linear, that we’d see Jenny the ape as anecdotes that are visualized, that this would be an emotional portrait of the man as opposed to a homilectic portrait of a saint. It was a five-minute pitch and Jeremy went “I like this very much, I think it could be very exciting!” Within a remarkably short time he had signed up and John Collee and I went off to write the script. Jeremy found the financing rather quickly. He confided in me last week that he believed if he tried to finance this film now instead of two years ago, he probably wouldn’t be able to do it. The landscape has changed that much in just a few years. It’s become a very difficult time to finance films for grownups. I’m extremely happy that I was able to slip under the wire so to speak and make this movie.

Filmmaker: You’ve made movies on broad canvases before, with large budgets in the studio system. This film was independently financed. How different was the process from the making of a Copycat or Entrapment?

Amiel: It’s not nearly as different as one might imagine. The basic truth, weather you’re making a studio movie or an indie movie, is that there is never enough time and never enough money. Somehow, miraculously, that always seems to be the case when you’re making movies. Generally there’s an equation, big money means big interference, less money means less interference. What one hopes for in an independent movie is the fact that you’re spending less of other people’s money means that you have less ambient anxiety to deal with and thus less interference. Sadly even that isn’t always true. You can find even on a small independent movie, that you put together your financing from six different sources, all of whom wish to have a voice in how the film is edited, marketed and distributed. So I don’t think the difference is really between studio movie versus indie movie. A lot more differences appear in the marketing and distribution stage of the film. That’s when you really notice a studio’s clout and marketing capabilities as opposed to independent distributors. It’s all about with whom and for whom you’re making the film. I got pretty lucky with Entrapment, Copycat, Summersby. I made those films with producers and for studios that essentially allowed me to make the movies that I wanted to make. I can look at all those movies and say, for better or worse, those are the movies I intended to make. I had relatively little interference and relatively substantial levels of support. That’s as true of those bigger studio movies as it was of Queen of Hearts and Tune in Tomorrow, my first feature films and this one.