Back to selection

Back to selection

Jane Campion’s Bright Star

Jane Campion's Bright Star

Jane Campion's Bright Star Chaste is not a word often associated with the films of Jane Campion. From the boudoirs of The Portrait of a Lady to the rough frontier bedrooms of The Piano (1993), Campion is known for her steamy, sultry visions of intimacy. But in her latest film, Bright Star, the only female filmmaker to win the Palme d’Or puts the gloves on, telling the tale of British poet John Keats and his love, Fanny Brawne, with modesty and restraint.

Keats died at the age of 25, before he could find the critical and financial success to wed his beloved. Yet Brawne, an accomplished seamstress, was committed to their relationship despite his worldly circumstances. Campion considers her a “love rebel,” a woman who could have hoped to for a wealthy husband, but instead chose to follow her heart. “It’s quite difficult to imagine the extent to which marriage would have ruled us girls and women,” Campion explains. “At the time, I think a good marriage was like a good job—one that would allow you to live the way you wanted—as opposed to be a crummy job. As long as the boss and the hours were okay, the job was great.”

For Campion, Bright Star reflects an interior mood, and grew out of a personal quest to understand Keats’s poetry. During time away from filmmaking after her contemporary thriller In the Cut, she felt a growing connection with the poet. So much so that when pre-production on the film began, Campion found herself startled by her project’s physical realization. “I can remember feeling overwhelmed in rehearsal when we always had so many people in the room; thinking, ‘What the fuck’s happening?’ she confided. “I’d spent most of my time alone, and then suddenly, in rehearsal, there were always four or five people around. I realized, ‘Oh! That’s because Fanny was hardly ever alone.’ That was the whole idea in those days—there was chaperoning in order to prevent what happened between Keats and Fanny from ever happening. Once people’s hearts are involved, it’s terribly difficult to undo it.”

Filmmaker: What brought you to Bright Star?

Jane Campion: This project was a surprise to me. After In the Cut (2003), I decided to take four years off. I made that choice as a mother, to be present bringing up my daughter, who was then eight or nine. But I also sensed, in a simple way, that I didn’t know who I was. I was 15 years old when I began filmmaking; I was curious to spend four years living quieter and finding out how I feel about things these days. Nobody thought I could manage it because I’m quite high-energy person. (Laughs) But I spent my time sewing. I embroidered pillow slips for my daughter and my friends.

I had read a biography of Keats by Andrew Motion [Keats (1998)] while researching In the Cut. There, I was creating a character that was a creative writing teacher. I felt vulnerable because I didn’t know much about poetry, something my character obviously would have been quite at home with. So I thought, “I’ll give myself a big delay with the writing, read this big fat biography, and I’ll maybe learn something.” About halfway through the story, Keats met Fanny, and from then on it was such a powerful tale of romance that I couldn’t believe it wasn’t better known. When you start reading their letters, you get an incredible sense of immediacy—they’re exactly the words Fanny would have read. For me, Keats’s letters were a portal into his poetry. I got the [Robert] Giddings book of his letters, and read them all. I found Keats absolutely adorable—so fresh and funny. His philosophy—his thoughts about negative capability, for example—were intriguing, and understanding him as a personality gave me courage to approach his poetry. He didn’t feel so different from myself.

I couldn’t imagine what the film’s story might be, however. I don’t really like biopics—I find them quite difficult. People these days, including myself, feel alienated from poetry, so a film about John Keats, the poet, seemed to me the most unwanted object in the world. (Laughs) But I hit upon the idea of telling the story from Fanny’s point of view, which would set some restrictions. I said to myself, “I won’t look at anything that she didn’t personally know about.” So it’s Fanny’s Keats, really. I also see it as a kind of ballad: The Ballad of Fanny and Keats. Of course it’s not the truth; I created a lot of scenes, like their first meeting and, well, ‘most everything. I kept the parameters of what I knew and what could be known to restrict and encircle me. I also didn’t try to up the ante. Instead of saying, “What interesting way could I do this?” I thought, “What is the most probable way that this would have happened?” I was relaxed and had very low expectations for where it might go. I just thought, “Well, this seems to be what I love,” and went ahead like that.

Filmmaker: Sewing and filmmaking share historical echoes; in early cinema, there were many women editors and editing was seen as a type of sewing. On your time off, did you sew pillow slips like the one Fanny makes in the film?

Campion: I didn’t do one as beautiful as that! (Laughs) I did one with horses for my daughter—she was crazy about horses at the time—and I probably got that idea for her pillow slips from my own sewing, yes. Fanny was an amazing seamstress. In her time, that’s how they made their wardrobes: by hand. Her sewing also represents a kind of patience that women had to have, or still have to have—a kind of patience that they learn. Sewing is a literal metaphor for making one’s will, stitch after stitch. Louise Bourgeois also has a lot of sewing and waiting in her work. I love that this film is an opportunity to look at the world, or look at an event, or at Keats happening, through the eyes of someone who was a sew-er and a wait-er.

It’s hard to make generalizations because there are a lot of patient men, too, but in times where opportunities were restricted, women managed to gain some great qualities—like patience. Patient people they do a lot less damage in the world. It’s the action heroes you’ve got to watch out for.

Filmmaker: Are you patient?

Campion: I think I am. I’m very persistent, and I take a long view. I always think in five- or three-year terms. I never mind what happens in the end, as long I like what I’m doing at the time. For example, if this film had never materialized, I still would have enjoyed writing the script. It always feels like it’s not going to happen, but I’m quite comfortable with that. I ask myself, “Am I enjoying what I’m doing what I’m doing right now?” And if I am, then it’s okay. The high moments are so fleeting. Going to Cannes, having your film in competition… That would seem like a high moment, but it really is over in the click of the fingers.

Filmmaker: How does Bright Star fit aesthetically with the stylized look of Sweetie (1989), Peel (1982) or your other films? Some directors’ visual styles define them, while you seem unusually comfortable moving between aesthetic realms.

Campion: For Bright Star, I wanted to experiment; to forget any “branded” look and find another way of looking at things. This story is so gentle and simple that I didn’t want you to feel any overreaching style. I wanted to disappear, really; that’s what I tried to do. What I cared about was the presence of those people, and any signature look would have been threatening to the more serious endeavor. Some people comment, “Oh, the film is very beautiful,” or whatever—that’s funny to me, because I never tried to make this film beautiful. If it is beautiful, it’s because of the sensations that it creates. In production, if a shot looked too beautiful we would say, “No. This isn’t right for this film, it should feel simple.”

During my time off, I started to do something that I’d never really done: go backwards and look at early films. My assistant was at film school, so she had access to lots of films. Bresson’s A Man Escaped (1956) was so tense and so simple—I really loved it, and you’re influenced by what you really love. I fell in love with his sense of classicism, and re-invented myself as a classicist. (Laughs) I put classicism down to ideas or thoughts about purity and simplicity. Not wanting to create sensation; not having an end in mind; letting the work discover its own impact. I realize that this story is very emotional, and the last thing I want is for people to feel manipulated. They’re going to have whatever reaction they have to it. Within my ballad idea, I just told it as straightforwardly as I could. When you see people who are trying to create a style that is impressive or something you just feel annoyed, “Oh, God. Sit down.”

I think I was more controlling in the earlier days. In Sweetie, I was straight out of film school and was experimenting without really knowing I was experimenting. We couldn’t afford all the tricks of the other guys, but we could afford to be daring about how we did things. I love Sweetie, it’s one of my favorite films. There’s nothing like innocence; you can never recreate it. Sweetie’s just Sweetie. But I didn’t think you could keep going that way. You just have to be where you are.

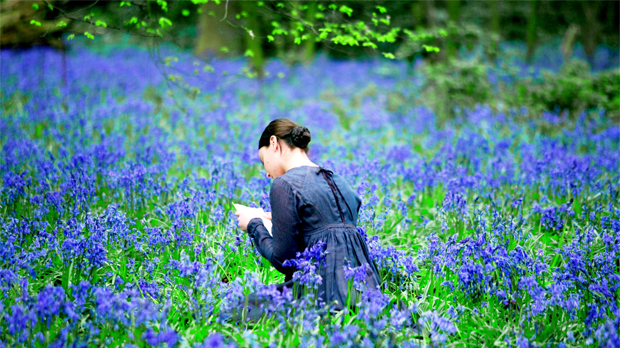

The Piano was experimenting with more epic kind of views, especially in regards to landscape, whereas Bright Star is more intimate. The English landscape isn’t as impressive as the New Zealand landscape, but it’s very darling. We were on location when we discovered that we were in a paddock with daffodils, or on the bluebell walk, for example. A lot of surprises popped up across the seasons as we were shooting. People are surprised that there are all actual real flowers, and that everything’s real in the film.

Shooting in London was difficult, because there was very little left from early 19th-century England. We worked at a place called Hyde House, which was about an hour from London. It was the first location we looked at, in fact. I thought, “Are we being very lazy?” (Laughs) We went upstairs and were exploring around when we saw a framed picture of the family after a hunt and in the background was a sign for a pub that said Bright Star! We thought, “We’re supposed to be here,” so we went to the pub and took a photo of the sign, which was a gorgeous deco-looking thing. I had it on my computer screen for a long time.

I love that things can work that way. Over time that we just kept using more and more things that they had on the estate that we weren’t expecting to use. We were lucky to have the Georgian house and the smaller one that we could use as a cottage on the property… Instead of thinking, “What’s the best, what’s the best? Ooh, I want that!” My experience is that the quieter you are, the more you notice that everything you need is around you.

Filmmaker: How does Bright Star fit in with your ongoing exploration of sexuality, and women’s sexuality in particular? Your representation of John and Fanny’s relationship is very chaste in comparison to other relationships that you have explored.

Campion: I think it was a chaste relationship. It definitely seems to have been so. I was grateful that that was the case, because I think an attraction of the story was its innocence and purity—not that sex isn’t innocent and pure, too! I’m sure that they did whatever they could; from the quality of the letters and the way that he talks to her, it seems pretty clear that they were close. The tenderness really struck me about the story; it provided the opportunity to explore delicate feelings as they first arise between people. How confusing and powerful they can be! The first indications of people being mutually interested are probably much tenser than the actual consummation of that interest.

Filmmaker: Do you think that is similar to the way that the characters of The Piano or The Portrait of a Lady (1996) viewed marriage?

Campion: See, I don’t think so. Each of those characters were in a kind of quarrel with their hearts and with good sense, which evaded them all. Isabel Archer made a devastating marriage. At least she knew it, and that could empower her at the end. Ada was pregnant without being married, so something had happened, some sort of passion or rebellion. In a quiet way, Fanny is also a love rebel. She chose for her heart, rather than for economic sense. It cost her a lot. It could have cost her almost her life, in a way, because she didn’t recover from Keats for many years. She wasn’t actually married to Keats, but she acted as if she was. After he died, she didn’t get married again until she was 33—for a beautiful young girl, that would have been a fairly devastating choice—and even then she married someone who was 21, perhaps remembering Keats’ youth.

Filmmaker: I love the friendship between the two men in Bright Star, and between the women in In the Cut and An Angel at My Table (1990). The women cuddle and share secrets; they have a unique kind of comfort with each other’s feelings and bodies.

Campion: Yes. In In the Cut, there was a moment between Jennifer Jason Leigh and Meg Ryan’s characters when I felt deeply thrilled because I guess it’s always been a latent mission to show that closeness that women have, the love they have for each other. In this film, it’s very clear that in a way, it’s a love triangle, because Brown really, really loved Keats too. Brown died in New Zealand, actually; he immigrated and died shortly thereafter. On his grave he had it read, “Friend of Keats.” So did Samuel [Brawne]. So did [John Hamilton] Reynolds. The sort of friendship they all had was probably the most powerful thing they had in their lives.

I really relate to that because I remember being at university in the days when you were flatting with your friends. The friendships were so powerful. It was probably the most joyous thing in life, that you had these great friends that you were going to do things with, explore the world with. I think Brown felt like he probably wouldn’t be able to realize his poetic hopes, but this guy Keats would. I think the feeling around Keats at the time from his friends was that Keats was somehow a genius. He had the right attitude and the right nature and ambition to achieve what they perhaps wanted to, though they could see they didn’t have quite the same talent.

Filmmaker: Is that similar to relationships that you’ve experienced?

Campion: I don’t think so. When you experience other talented people around you and are moved by their talent, you wonder what’s going to happen to them. Sometimes terrible things happen. The girl I think was the most brilliant in art school had a mental breakdown–like her mind was on fire and she just tipped over. She was an unlikely person, an Italian immigrant from a very conservative family who didn’t have any idea what she was thinking or doing.

The combinations required to bring a working relationship with your talent to the world are curious and strange. I’ve seen a lot of young women, whose work I thought was just amazing, just drop out. People I consider vastly more talented than myself… It’s heartbreaking. They cannot bear the stress, I think, of criticism. You ask, “Why didn’t you make another one?” It’s not worth it to them, it’s just too much. Too tough, too cruel, too intense.

In film school, we supported each other. A group of us used to work at night rather than during the day hours. We’d arrive at three in the afternoon and work through to six a.m. There was no one else in school at the time and it was fantastic. Those students taught me what I know.

Filmmaker: How would you describe your current collaborations?

Campion: As I’ve gotten older, I’ve become more relaxed about collaboration, and more grateful for everything that it brings. When I was younger, I felt a lot of stress about controlling the project. I wasn’t very adaptable to seeing in a different way, or seeing how other people’s contributions could add to what we were trying to do. It could feel like a threat. “Not my way!” (Laughs) Of course you’re careful to choose people where you like what they’re doing, and now I really enjoy what different people can bring.

On this film, I worked with quite a lot of people, and many who are quite young. Janet Patterson, of course, I’ve worked with forever. During those four years off, I made a little short film for the United Nations where we tried some of these young people. We had to, because we couldn’t afford more collaborators, but it was also a conscious decision to work with some new people. Greig Fraser, who is the D.O.P., and Mark Bradshaw [the composer] also worked on that short film—and I really enjoyed the way they did their work. I thought they were fantastic: the energy, the way they approached things. It was pretty easy choice to work with them again, although some people would’ve thought it was risky to use a 23- or 24-year-old composer without any credits. (Laughs) He’s got a credit now! But I thought, “Hello, Keats was 23 when he wrote his major works. When is anybody going to trust anybody?” At 15, I remember feeling like, “I know everything that the adults know. I haven’t had any experience with it, but I can see the same things.”

I really think there’s nothing stopping what a 23-year-old doing what a 32-year old could do. It’s quite thrilling, in a way. Looking back at a different time—the 19th-century, the 1820s, when so many died so young—there was a feeling that if you were talented, get on with it, because your life might not last very long. Now’s the time. So when Keats wrote, “When I have fears that I may cease to be/Before my pen has glean’d my teeming brain,” he must’ve felt, “God, I’m going to die not having done what I can do!” He keeps calming himself by looking at the wide world and feeling his smallness.

Filmmaker: Is that odds with being patient?

Campion: Definitely. Keats always worked in opposites. He often talked about wanting the stability—as in Bright Star itself—of a distant star, which seems ever steady; but at the same time, wishing for the closeness of breath against his cheek or something, and knowing the two things were incompatible. I guess that’s the charm of humans: wanting the impossible.

Filmmaker: I’ve often noticed your characters’ animal impersonations. In your third short film, there’s an intense sex scene between the two young people who begin by imitating cats.

Campion: I don’t know why, but I love cats. When I first saw Ben Wishaw, I thought, “Oh my God, he’s a cat.” (Laughs) He was waiting outside the audition doo, and he just looked like the most beautiful black cat you’d ever seen. I think there is a mysterious quality to people that apparently can be brushed over because they speak. (Laughter) But it’s their creature quality that I fall in love with. I like people who don’t talk.

Oh, the casting process! It’s quite frightening, I think, because you’re making the most important decisions about your film—when you know the least about it. (Laughs) In this situation, I didn’t even get to see Ben and Abbie together. I had photographs, could blow them up so they can be whatever equivalent size and put them together, could find out their heights, but I couldn’t know in advance how they’d look, how they’d be.

Filmmaker: Did they look and work together the way you expected?

Campion: It was better than I was hoping, actually. They really liked each other, in an animal way, immediately. Both of them are bad liars, so it wouldn’t have worked otherwise. (Laughs) You have to be an incredible optimist, and a pessimist at the same time. You have to imagine all the problems, and then take a cheery attitude and work it out.