Back to selection

Back to selection

IN ROTTERDAM, AMERICAN FILMS THAT COULDN’T EXIST ANYWHERE ELSE

After the rush of sales in Park City this year, it seems the entire American cine-punditry is racing to declare this the beginning of a new golden age in American Independent Film. I sure hope they’re right. One wonders if March’s SXSW Film Festival in Austin will continue the trend and finally push that festival into true market status. Nearly 40 films were acquired in Park City and many more that premiered there will surely be acquired in the weeks and months to come. Yet for some of the most daring new American films, the sales rat race at Sundance isn’t an aspiration. After returning from Rotterdam, where the 40th International Film Festival Rotterdam is still unspooling through this weekend, I can say that the health of our non-commercial cinema, that from the children of our incredibly rich American Avant-Garde tradition and one that has long been supported by Rotterdam’s challenging and heady programming, is as strong as it’s been in some time, regardless of it’s non-commodified status.

Several of the leading lights of contemporary American Avant-Garde cinema were in Rotterdam with new work. Of course, it’s impossible to catch them all. This is the type of festival where you may not be aware that Ken Jacobs or Harmony Korine has short work there until you get to the airport and closely study the massive catalogue of over 280 features and 400 shorts. Ben Russell, who was in the Tiger Award feature competition last year with his stunning, 13-shot trans-ethnographic rumination on the path Surinamese captives took to escape their Dutch captors and the bondage of slavery in Let Each One Go Where He May, was back this year with the seventh of his “Trypps” films, a series of shorts which deal with the literal and associative evocations of the word “trip.” His newest entry in the series, a one-shot piece that begins in medium close-up on a brunette, standing on the edge of a cliff, staring into the lens as the camera moves ever so gently up and down, gradually revealing that the movement, which becomes a vertical, 360 degree loop, may not be the camera at all, but a well positioned mirror. The film, which by the end evolves into total abstraction, is an investigation into the ways we construct an internally generated version of our lovers versus seeing them as they are; romantic self-construction is as universal as dopamine.

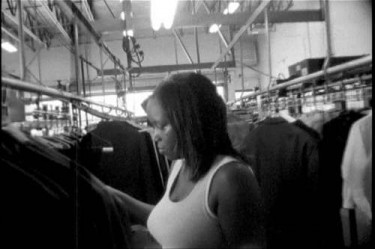

Kevin Jerome Everson, a model of the strictly non-commercial, institutionally-supported post-New American Cinema avant-gardist, was in Rotterdam with his new feature Quality Control, which meditates upon the souls of black folks in an industrial dry cleaning operation outside of Mobile, Alabama. The University of Virginia associate professor and 2006 Filmmaker Magazine 25 New Face in Independent Film pushes cinema’s observational mode to a near breaking point, finding a hypnotic composition with his Bolex, usually one in which the charming and resilient men and women who work in the place are surrounded or dwarfed by the machines they both operate and fall victim to, and he gazes as far into it as he can. Everson invites the audience to look deep into his frames, to be an active participant in them or to simply be washed away by their undeniable force. Often in Everson’s work, one reaches a point of sublime exhaustion. Only toward the end of his most recent picture does the style grow more reportorial, complete with close-ups and voiceover from a young woman who’s smile carries more of a charge than any you’ll witness in a cinema this year.

While this style has similarities to the early documentary work of Chantal Akerman, there is even less authorial will exerted by Everson upon his subjects; his shots are rarely arranged and edited to have any causal relation, but are unified by his insistence of the unique and startling humanity and behavior of the types of African-Americans who made their way north to places like Mansfield, Ohio, where Everson was born and still spends a fair amount of time. While not as haunting and beautiful as his 2009 feature Erie, Quality Control is perhaps his most rigorous feature yet; one wonders if he’ll return to the mix of found footage and docu-fiction hybrid, reminiscent of Jia Zhangke and Alain Resnais, that was the hallmark of his earliest features, Spicebush (2005) and Cinnamon (2006), which somewhat ironically played at Sundance in the New Frontier section. If you’re not hip to his work yet, New Yorkers, he’ll have his own show at the Whitney later in the year. One would be remiss not to look out for it.

More conventional American narratives were in Rotterdam this year, although it’s hard to find anything conventional about Michael Tully’s terrific Septien, which bowed just a few days prior at Sundance, or Kitao Sakurai’s beguiling Aardvark, a strange and memorable tale from Cleveland, Ohio about a blind man who becomes an amateur sleuth when his black martial arts instructor is murdered. Ravishing to look at, it has a someone pat and ironic ending that will leave some cold (the director himself gets a few bullets in the grill), but is otherwise well worth your 90 minutes. Among the American world premieres was R. Alverson’s New Jerusalem, a thoughtful and odd misfire with Will Oldham as a bald headed, born again Christian mechanic who ministers to an Irish co-worker who happens to be an Afghan war vet, and Matthew Petock’s reasonably effective, often affecting A Little Closer, about a single mother and her two sons struggling to get by and be happy in the American South.

The real find among the American narratives was most certainly Malcolm Murray’s Bad Posture, an anti-mumblecore western populated by non-actors. Set in the director’s hometown of Albuquerque, New Mexico, it follows an awkward, unassuming graffiti artist named Fl0 (Florian Brozek, who also wrote the film), newly unemployed for smoking too many cigarettes on the job, who begins to hit on a girl in a park but is thwarted when his roommate steals her purse and car while he’s laying on his mac moves. “Didn’t you see me talking to that girl?” he asks as they drive away in her car. “Of course man, but I’m trying to pay our rent here,” says his adorable, matter of fact, thief of a roomie. They trade the car to a chop shop owner for $400 and an AK-47 and so begins this leisurely, deadpan hilarious, sneakily ambitious narrative, in which Flor spends his days pining for a way to meet that young woman again, when he’s not unintentionally discharging firearms into their toilet during domestic disputes or handing out flyers for the party at his place that weekend. Murray, who also shot and edited, has a real feel for this milieu, in which everyone seems to have a gun and copious amounts of bud, but no one seems to be a real threat to anyone else. This is a gentle, intelligent and relatively sweet movie about gun owners and potheads in the American southwest that doesn’t feel like anything I’ve quite come across in recent American DIY cinema.

Of course, I got a slow start in Rotterdam this year. Jetlag will do funny things to you. I spent my first day on Dutch soil in bed, attempting to find some circadian equilibrium and ruminating on some of terrific titles I caught in my final hours in Park City. The two that most clearly stood out, Rashaad Ernesto Green’s stirring Puerto Rican tranny drama Gun Hill Road and Sebastien Pilote’s quietly stunning, Quebecer wintertime dramedy The Salesman, received far less attention than they deserved in Park City, although Green’s feature debut was acquired by Motion Film Group toward the festival’s end, assuring that it will make its way to American screens sometime soon. Gun Hill Road strongly resembles Dee Rees‘ Pariah in its exploration of an outcast LGBT teenage minority from New York City’s outer boroughs who struggles to find familial acceptance and dabbles in poetry, but his film is a bit more ambitious thematically if not as handsome aesthetically. He gives us a fully developed familial antagonist in Esai Morales’ patriarch, fresh out of Rikers, who is adjusting to civilian life. He masculine self-image (already assailed by sexual assaults while incarcerated) is quickly hindered by the realization that his son dresses in women’s clothing and behaves in an effeminate manner. Green is bravely willing to risk his audience’s affection for his characters at several points in the narrative and doesn’t offer any hope of false redemption. This is a strong, buoyant debut by a director of great promise.