Back to selection

Back to selection

American Idol: Tabloid Director Errol Morris

As globalism renders the world ever smaller, national boundaries seem increasingly porous, if not outright irrelevant to the study of cinema. Yet Errol Morris still strikes me as a distinctly American filmmaker. From pet cemeteries in California (Gates of Heaven) to death row in Texas (The Thin Blue Line), from the Vietnam War (The Fog of War) to the Iraq War (Standard Operating Procedure), and in ads for the presidential campaigns of John Kerry and Barack Obama, Morris tends to bring his insatiable curiosity and searing intellect to stories and characters that, for all their strangeness and improbability, are inseparable from American history, American scandal, and American myth.

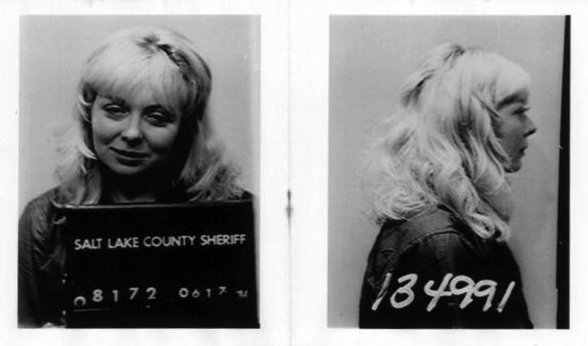

In Tabloid, his newest and perhaps sweetest cinematic confection, Morris turns his attention to the tale of former Miss Wyoming Joyce McKinney, her captive “manacled Mormon” love interest, and the five pit-bull clones she commissioned from the DNA of a favorite pet. It’s a zany, utterly improbable story that nevertheless comes to epitomize the American dream and American derring-do. “The whole beauty queen story is an American story. The crazy pursuit of her boyfriend in Mormon Utah is American. Joyce’s retreat to North Carolina, that’s very American, too,” Morris explained to me at the time of his film’s premiere on the festival circuit.

Yet like the best, most essentialist of national cinema, even when Morris’s subjects are as American as apple pie (or freedom fries) the ideas threading through his narratives are universal. He is captivated by what G. K. Chesterton called “self-hypnosis”: the lengths to which people—or any being, for that matter—go to as a result of their convictions. As Morris recently wrote on the social media site Twitter (to which he admits an addiction): “QUERY: Roundworms have 302 neurons and 8,000 synapses, but how many are needed for roundworm delusions…e.g., the roundworm that believes that it’s segmented and can’t be disabused of that notion?”

With his first fiction film since The Dark Wind in the pipeline (it reportedly involves Paul Rudd, Ira Glass, and cryogenic freezing), several books on the verge of publication, and Tabloid, which he considers his best film, about to hit theaters, Morris is at the top of his game. His inquiries into what makes one of us tick lead swiftly into questions about what makes all of us tick. By delving deeply into these American stories—and into the stories behind the stories—he arrives at the values common to us all.

In this wide-ranging and personal discussion, Errol Morris talks about women, religion, and rescuing substantive, meaty complexity from mere tabloid fodder.

Morris: Well, good. That’s another film, and it was done relatively quickly: less than a year from when I first started making it.

Filmmaker: That’s a record.

Morris: The longest was the Thin Blue Line, because I was investigating while I was shooting, which always adds time. Here, although we were also investigating, there were only six interviews, and that’s simpler.

Filmmaker: Is this your first film to include a non-English interview?

Morris: That’s true. [Cloning scientist] Dr. Jin Han Hong could speak English, so we did a whole part of the interview in English. But I thought it was much better in Korean—it’s stranger and more wonderful when he comes onscreen.

Filmmaker: Do you still subscribe to The National Enquirer?

Morris: I used to subscribe to both The Weekly World News and The National Enquirer, but then the Enquirer became kind of a celebrity rag. It stopped publishing eccentric stories the way they used to in the old days. There are two versions of “tabloid”: the version that is celebrity-driven, and then the crazy, crazy story that’s really hard to believe. The one cinema vérité documentary I dreamed of making would have been going down to the offices of The Weekly World News and just hanging out—Fred Wiseman style—for two weeks. But The Weekly World News went under. The public’s appetite for that stuff has changed. It’s become more of a celebrity-driven culture, instead of a culture centered around oddballs and oddities that tabloids like The Weekly World News used to cover. Maybe that’s what makes Joyce interesting: she’s right at that intersection.

Filmmaker: In many ways, your stories are distinctly American: Vietnam to Abu Ghraib, and from capitalist pet cemeteries in California to the opportunistic death row in Texas. Is Joyce McKinney’s story is a uniquely American tale?

Morris: It’s true that the whole beauty queen story is an American story. The crazy pursuit of her boyfriend in Mormon Utah is American. Joyce’s retreat to North Carolina, that’s very American, too. But oddly enough, this story had no traction in the United States. It never got publicity in America. It became a huge deal in the UK. A British guy came up to me at the screening last night who said that he remembers the story. The story was everywhere; it was ubiquitous. That may be because we have a different sense of sleaze or tabloid. This is something that really appealed to the British, whether it was the sex and chains aspect or… probably the sex and chains aspect of the story. (Laughter)

Filmmaker: Was it difficult to convince Joyce McKinney to participate in Tabloid?

Morris: She didn’t say ‘yes’ right away. When I first read about her, I believe she was in North Carolina. I talked to her and she was not interested in being interviewed at that time. I’m amazed she talked to me at all. But then I called her probably three, four months after that fact, and she was interested. A lot of how the news works is that people are interested in the story for 48 hours, and then they lose interest. Often, if you wait and approach someone like Joyce months after the fact, everything’s changed. In this case, then she was willing.

Filmmaker: What was your pitch to her?

Morris: The idea was that I would tell her story, and that I would at least do a better job than most. I don’t know if ultimately it’s going to be a job that she is completely enthusiastic about, though I think that in the film, she becomes a kind of romantic hero. An odd and unlikely romantic heroine… but a romantic heroine nonetheless.

Filmmaker: Do you consider yourself a romantic?

Morris: I probably am, on some level, even though I would deny it. I’m moved by Joyce. I’m also endlessly fascinated by people who—maybe it’s true of all of us—but some people are more successful than others at creating a strange reality around themselves and living in it with utter conviction. In Joyce’s case, she has created this love story involving this one person: herself. It’s really quite remarkable. The fact is that we really don’t know the underlying reality of this story. On some level we know, and other levels we’re virtually clueless. When Kent Gannon asked Steve Moskowitz if he’d ever had sex with Joyce, he answered, “No one has ever had sex with Joyce. No one.” I wonder if it’s really true. Maybe she never had sex with anybody. Maybe she never had sex with Kirk. Maybe all of this was some kind of elaborate fantasy. What if it’s true that she’s the virgin nun and the whore?

Filmmaker: Something for everyone. (Laughter) This film is a more explicit exploration of religion than I’ve seen from you before.

Morris: You’ll have to tell me why you think that’s something you’ve never seen before. I’m curious.

Filmmaker: Religion is front and center here, whereas your other films tend to be more philosophical. It’s interesting, in this film, to see you dealing with religion as a religion.

Morris: In this story, people are involved in these weird turf battles: ‘Kirk is mine.’ ‘No, he’s mine.’ ‘No, he’s mine.’ Joyce sees it as a battle. I don’t really know what Joyce thinks of the film even though she’s seen it and she has a copy of it. Part of her would really like to see a film that is a screed against the Mormon Church. She would like me to take on the Mormon Church. I think that’s part of the story, but I don’t think it’s the story. Do I believe that the Mormons played a nasty hand in all of this? I kind of do. But do I know? I really don’t know.

Filmmaker: How does her vision of religion compare to yours?

Morris: My version of religion is doing things that, if my mother were still alive, would please her. And that includes occasionally going to shul.

Filmmaker: When do you go to shul?

Morris: Oh, very occasionally. I should have gone in the last week, and I didn’t at the last minute. I was bar mitzvah-ed, though for a while, I would pretend I wasn’t a Jew. Then, when I was at University of Wisconsin, there was this guy named Isaac Fox—very, very smart. I’d always tell him I was Episcopalian or something. Then, one day I looked at Isaac and I said, ‘You know, Isaac, I’m really Jewish.’ And he said ‘No you’re not.’ And I said ‘No, no, no, I really am Jewish.’ I started singing the Four Questions: “Mah nishtanah, ha-laylah ha-zeh, mi-kol ha-leylot.” I saw this look on Isaac’s face, “Oh my God.” When I was in Bubbling Well Pet Memorial Park, having dinner with the Harbert’s family—Scottie, Cal, the two sons — on the middle of the dinner, Scottie’s brother says, “Are you a Jew?” And before I had a chance to answer, Scottie said, “Don’t insult him!”

I actually am proud of being a Jew. I go through all kinds of weird feelings about it but yes, I’m proud of being Jewish. I don’t ultimately know what it means in terms of religious experience, but it must mean a lot. Maybe I just haven’t been able to factor it all out in my mind. I’ve often wondered why I love pariahs; and maybe that’s a Jewish thing. It could be. If people really strongly disapprove of something, I am usually curious about it. I usually imagine there’s a deeper, more interesting story to be told—whether it’s Joyce McKinney, or Robert McNamara, or Lynndie England, or Randall Dale Adams, or a whole mess of characters that have fascinated me over the years.

Filmmaker: You once told me that Standard Operating Procedure was a girls’ story, a women’s story. How does Joyce’s character compare to the women in that film?

Morris: I’m tortured about SOP because I have received so much negative criticism about that movie. Someone asked me recently how I take criticism, and I said “Badly, just like everybody else.” I was asked to write an essay for Daedalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and I’m working on that now. I wanted to write on simplistic interpretations of bad things, and Abu Ghraib in particular. I like the idea of recovering the individual from this morass of presumption and assumptions. It’s recovering Sabrina Harman and Lynndie England from what is, in essence, a huge tabloid story. I didn’t really get anywhere close to the heart of it, but there is a kind of love story—a really sad, failed love story—at the heart of Lynndie England’s story. See, this is the crazy part of me, I’m actually moved by… I like women, and I like those women. I don’t find them to be monstrous, and I don’t find Joyce in any way to be unsympathetic. I like her.

Filmmaker: What do you like about these women?

Morris: During production on Mr. Death, I was at Stouffer’s down in Nashville having breakfast with my producer, Kathy Trustman, Fred, and his then-wife Carolyn. One of the weirdest breakfasts I’ve ever had. There were two conversations going on at the table: a boys conversation and a girls conversation. The girls—Kathy and Carolyn—are talking family, emotions, children. And since I’m with Fred, the boys are talking about botched executions.

Filmmaker: Same thing, really. (Laughter)

Morris: I kept trying to listen to the girls’ conversation because I’d heard the boys’ conversation before and I was kind of worn out by it. But in the middle of this, Carolyn started screaming, “Must you? Must you go on like this all the time? Must you?” I don’t understand Joyce. I guess, Tabloid is obviously a girls’ story, and a story about eternal love, fulfillment, having a child. While I was editing this thing and executives would come to look at it, they said, “You should just take out the dog cloning; it has nothing to do with this previous story.” Joyce herself raises that question. “What does a 32-year-old sex and chains story have to do with dog cloning?” One of the things that makes that line funny is that, if the movie is working, you see exactly what it has to do with it. “We’re pregnant! We’re pregnant!” She finally achieved this dream of having a child, or five children. It’s crazy and bizarre, but nevertheless it’s kind of a fulfillment of some dream. The power of some weird dream…

And I’m sure I’ve told you, I was brought up by women. Lucky for me.

Filmmaker: Your mom, your aunt, your housekeeper…

Morris: Yes; my mom, my Hardy—they really saved me.

Filmmaker: Do the women in your films remind you of the women you love in your family?

Morris: In many ways they do. I don’t think I would want Joyce as my mom, or Sabrina or Lindy. I have all these theories about why people are annoyed by Standard Operating Procedure. You know, I keep tweeting — I can’t stop myself even though I know I should probably never do it—and I tweeted something, and then removed it, saying, ‘Documentaries: is it possible to make a really bad movie about a worthy subject?’ And then someone commented that Standard Operating Procedure was a bad movie about a worthy subject. Which may be true. I don’t even know what I think about that movie anymore, although I do know that the issues I was trying to address are still important and interesting to me. Whether I was successful at addressing them or not, I’ll never know. But I like this movie, Tabloid. I could say, ‘Well, I’ve gone back to doing eccentric subjects.’ But all these subjects are eccentric subjects—Robert McNamara [in The Fog of War] is probably the most eccentric subject of all. The difference is that there’s no label on Tabloid that says, “I am important.” There’s a label on Fog of War: you interview Robert S. McNamara; Robert S. McNamara is an important person; by extension, I suppose, the movie is an important movie. Or Abu Ghraib is an important tabloid story. It is, properly considered, tabloid; that was the essence of it. It was a story that got the same kind of superficial treatment that a tabloid story would get, without any desire to penetrate beyond the tabloid surface that appeared in the papers. This doesn’t have that label, “I am an important story.” In fact, it almost has the label, “I am not an important story.”

At least one or two people have already written in print, “Was it worthy of a movie?” You don’t make movies because the subject matter is “worthy of a movie.” You make movies that you think have something to say. Gates of Heaven is not an “important” subject, nor is Vernon, Florida. In a way, my affection goes to those movies for that reason alone. They don’t have that crutch of saying “I’m involved in saving the whales or making the world a better place for future generations or ending global warming” or doing any number of valetudinarian things. I’m just telling a kind of story that is personally meaningful to me: a woman’s almost absurd but deeply romantic quest for love. Though my favorite stuff in the movie are those home movies that she took where nothing is happening. They’re great.

Livia Bloom is a regular contributor to Filmmaker and the editor of the book Errol Morris: Interviews.