Back to selection

Back to selection

The Cinema is a Train: On Steven McQueen’s Hunger

The Cinema is the Train: Part One

Economy of Narrative + Abundance of Truth = Poetry in Cinema

In an earlier essay for Filmmaker, I argued that “…cinema’s ‘vocabulary of forms’ is typically under-utilized… While there are any number of cinematic languages that could exist, most of the time films tend to rely heavily upon what we could call the basics of film grammar – shot/counter-shot, close-ups, wide shots, over-the-shoulders and reverses, as well as certain editing paces and conventions of lighting and score,” and went on to praise Enter The Void for its progressive formalism.

In keeping with Jean-Luc Godard’s dictum inspired by one of the first films ever made – “The cinema is not the station, the cinema is the train” – this series aims to explore potential new directions in cinematic style, where that train might be headed. Whether or not the Mumblecore filmmaking of the early-to-mid aughts constitutes a movement is still up for debate; if it doesn’t, cinema hasn’t had a bona fide movement since Dogme 95. As American independent cinema becomes increasingly difficult to finance, and artistic filmmakers find themselves forced to make genre films in order to produce work, it is imperative to reassert the primacy of the medium as an art form. Independent cinema may be in a difficult place at the moment, but the desire for artistic representation is as old as humanity itself, and this industry isn’t going anywhere. Neither will its capacity for challenging, serious work that pushes the limits of what is possible in filmmaking.

In 10th grade I had an English teacher who provided a particularly compelling definition of poetry. “Poetry,” he stated, “is the evocation of a meaning or series of meanings in less words than would be necessary for the reader to articulate the meaning of the poem.” In layman’s terms, poetry operates by saying more with less. Into as little as a paltry line or two it packs worlds of meaning, thematic content, feeling and sentiment. A few words, if delivered properly, can require an entire essay to explicate.

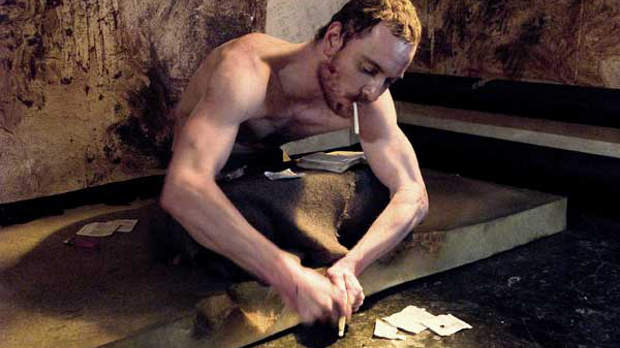

Trying to make a summation of the formalist credo of as complex and accomplished a film as Steve McQueen’s Hunger is perhaps an exercise in futility, but we can start by asserting that Hunger’s style is something like a pure form of cinematic poetry, if you’ll accept my English teacher’s definition. In Hunger, the devil is in the details, and the tiniest bits of onscreen presentation evoke a world of offscreen meaning: a prison officer takes a routine peek under his car; people bang garbage lids in the street; a cigarette is smoked by a guard with bloody knuckles. These are not moments in scenes, but the scenes themselves. Exposition is pretty much non-existent, except for a few title cards in the beginning. Contextual detail is tossed to the wayside. Dialogue, too, is usually truncated: we get a wisp of a Margaret Thatcher speech, a snatch of talk radio, the tail end of a prison guard telling a joke to his co-workers.

The film is ostensibly about the 1981 IRA “blanket” and “no wash” protests in the Maze Prison in Northern Ireland, and the hunger strike that followed, began by Bobby Sands. In actuality, due to the film’s stylistic choices, it is about both more and less: it’s about the specific living conditions of those imprisoned in the Maze, while remaining disconnected from the larger political situation, and it’s also about the universal human struggle of oppressed against oppressor, a struggle that is grounded in a base physicality that the film makes a primary visual focus. “When you’re in prison, you’re pushed to the absolute extreme,” McQueen told me in an interview. “And you use your body as a weapon not only to protest, you use your body to die.”

Hunger is able to make itself be about both more and less than what it “should” be about (judged by a traditional way of understanding narrative) by treating story structure with the same elliptical style it employs to make tiny moments metaphors for larger truths. Consider the film’s dazzling first-act structure: we are introduced to a middle-class, middle-aged man who seems to be checking under his car for bombs; soon thereafter, we see him listening to conservative talk radio. We learn after that he’s a prison guard at the Maze, and see him joking around with some friends. All this with basically no dialogue or storyline of any sort. Only then does the film’s perspective shift to the side of the prisoners, where it will rest for the remainder of the film. We are introduced to a new prisoner, who refuses to wear the prison uniform, like his comrades. We then get glimpses of what life is like for prisoners in the Maze – smearing their feces on the walls of their cell and dumping urine into the hallways in protest; living amongst maggots and stench; taking simple pleasure in the usage of a contraband radio; the utter boredom that leads one prisoner to study a fly with something like wonder; an attempt at masturbation that is aborted out of fear of one’s cellmate noticing. Again, this is all supplied with little to no narrative or character development of any traditional sort – we merely observe the prisoners in action, almost like anthropologists. We see the brutality of the prison guards, and later, the corresponding rage of the prisoners, which finds expression in a riot squad beating scene that is perhaps the most visceral in the film.

McQueen employs two formal gambits that enable Hunger to rise far above the limits of traditional cinema. The first, as mentioned, is the way he eschews traditional exposition in scenes for a single detail here or there, allowing an emphasis on one element (a gash on a prisoner’s head, a few lines of a Thatcher speech) to stand in for a much larger piece of the story being evoked (the de rigueur brutality of the prison guards, the staunchness of the British government’s position). The second is how, by presenting a narrative that has no traditional protagonist or story, McQueen forces the audience to do two things: 1) concentrate with extreme vigilance on every tiny detail in each scene, since so little information is being provided to the audience about what is actually “going on” in the film, and 2) piece together the larger narrative of the film themselves, once it becomes apparent that McQueen isn’t interested in doing it for them. The one-two punch of this poetic use of detail as metaphor and the refusal to let the audience get narratively comfortable is what makes Hunger a formalist knockout; it’s a film that won’t piece the details together for you into a cohesive storyline, because hey, the details are powerful enough to speak for themselves, and if you can’t respect that, fuck you. One almost senses that McQueen feels that tying the film’s narrative together in a traditional storyline would be doing the deadly serious nature of what is being represented a disservice.

The idea of the details being powerful enough to speak for themselves is part of what gives Hunger its gravitas. As that is the case, McQueen’s storytelling is based on an economy of visual information. Consider a cut toward the end of the first act. After placing the prisoners in new, clean cells and giving them new sets of clothes (which the guards know they won’t accept), due to what seems to be a procedural necessity, the prisoners begin to riot, destroying the beds, their frames, the desks, whatever they can get their hands on. They go completely apeshit, letting out primal screams, smashing the doors with pieces of furniture that they have now fashioned into weapons. Then, an abrupt cut, from the noise of this scene to utter silence, as we look into the face of what is unmistakably a riot squad policeman, in something like a SWAT van. The look on the face of that officer is one of trepidation and terror. In an instant, in one cut, McQueen has evoked a complex sentiment: that the prisoners’ protestations will be met with no mercy, only utter brutality, but that those who are delivering the brutality may not only feel terrified by its prospect themselves, but ethically conflicted, or worse. That’s cinematic poetry.

It’s an economy of exposition; the cut conveys a maximum amount of information with minimal narrative expenditure. Consider how the sequence might have been treated by a more traditionally-minded filmmaker. We get the sequence of the prisoners, beginning to riot. One of the prisoners shouts out something that explains why, exactly, they are rioting (“We will never submit to wearing your civilian clothes! We are political prisoners and deserve political status!”). We cut to the prison officers, one of whom makes some comment about how “This is the last time they pull this shit, God damn it. Call in the riot squad!” He adds some comment about how they should really show “no mercy” to the prisoners this time. We cut to inside the riot squad van, where their commander is laying out to them, in no uncertain terms, how they will go about “diffusing the situation.” But we wouldn’t get the close-up of the young officer, terrified; we’d see the rest of the officers in a group, as faceless henchmen. And we certainly wouldn’t get the transcendent shot that McQueen closes the sequence with, a split-screen of the riot squad guards beating a prisoner while we see the young, scared guard outside, by himself, weeping.

The sparseness of McQueen’s formal delivery, his utter disregard for providing exposition or context of any sort, is what gives this film its life-or-death level of self-importance. By taking such a harsh attitude toward exposition, Hunger also operates as a work of film criticism, showing how more traditional films, like the sort that would treat the riot sequence as done above, are cutting themselves off at the legs. Hollywood films in particular (but not exclusively) seem to believe that audiences are comprised of people with a 5th grader’s sense of intellectual comprehension. The result not only insults the audience’s intelligence, but more importantly, it insults the film’s intelligence – by insisting on spelling out every key plot detail in black and white, films compromise themselves, losing any chance for weightiness by engaging in a narrative style that comes across, at best, as cleverly contrived, but contrived nevertheless.

McQueen’s style is easier said than done; simply cutting out exposition does not a masterpiece make. The reason Hunger has so much merit as a work of art is that it constantly is able, in the economy of narrative it employs, to find that one shot, the one visual, that instantly and totally conveys an enormous amount of meaning and truth. In the shot of the prison guard looking under his car, or the shot immediately thereafter of his wife watching him turn the ignition, worried; in the shot of the terrified riot squad guard, or the shot soon thereafter of him weeping; in the moment in the film’s third act where an emaciated Sands refuses to ask an Ulster Defense Association-member guard for help in getting out of a bathtub, and consequently collapses — these instants in time are so perfectly chosen, so totally apt for conveying what McQueen wants to convey, that the narrative gambit works. If his moments of meaning were not as profound or wisely chosen, the film would be a disaster.

Hunger runs at a lean 96 minutes, and it almost plays like a strung-together compilation of the best scenes of a longer, more comprehensive film. This film would fill in all the blanks, all of the narrative gaps that surely frustrate some viewers. It contains scenes of IRA leadership debating what to do; scenes of Bobby’s parents worrying over the fate of their perhaps-too-principled son; scenes of Bobby meeting with visitors, discreetly discussing the hunger strike he is about to implement. Of course, those scenes wouldn’t have existed because they were necessary to McQueen’s project; they would have existed because cinematic narrative tradition dictates that they should. If a movie is a machine, and the best scenes are the moving parts, these sort of scenes are the grease that lubricates the wheels, that gets everything working properly, that connect sequence A to sequence C. McQueen has made a film that eschews the grease, the lubrication; Hunger is made up of only the scenes that Hunger could not live without; McQueen has no problem going directly from A to C. So naturally, scenes of narrative exposition, talky dialogue, and generic plot development are out (with one crucial exception, which I’ll get to shortly). Hunger is a film about politics, and in politics, actions speak far, far louder than words. Indeed, what emerges as one watches Hunger is just how enormous the gulf is between a few people casually debating a political issue, and the people who are actually sacrificing their bodies, their physical being, for the sake of that issue. It’s in this insistence that Hunger makes a beautifully articulated point about how politics really is a corporeal endeavor.

There’s an entire section of Hunger that might seem to refute much of what I’ve been saying. The film’s second act is a 22-minute conversation between Sands and a priest, which starts off as small talk and moves on to debating the ethics of the proposed hunger strike. It provides contextual information regarding the Troubles (“The IRA has backed itself into a corner,” the priest says at one point) and the reasoning behind Bobby’s decision (“I have my belief, and in all its simplicity that is the most powerful thing”). Yet this conversation, despite containing significant exposition and providing context to the film’s story, does not cheapen the power of the film in any way; quite the opposite, it may be one of the most moving and powerful conversations I’ve ever seen on film. Where does the scene’s power derive from? In addition to the obvious answer, which is that it’s incredibly well-written and well-acted, with the first 17 minutes knocked out in one take, it’s the contextual placement of the scene within the larger film. For the first 40 minutes or so of Hunger, we are watching a film that has barely any dialogue, and certainly no dialogue of real substance in relation to the film’s narrative. By the time we arrive at the scene between the priest and Sands, we have been retrained by McQueen’s formalism. There is plenty of room for fluctuation in the level of attention a typical audience member pays to a typical dialogue scene in a typical film – based on the interest level of that viewer, it could be anywhere from significant attentiveness to significant disinterest. One would be hard-pressed to find a viewer of Hunger who isn’t hanging on to every word of that conversation scene. After being deprived of dialogue for so long, we are hungry for it, and, becoming appreciative of something we once thought was to be taken for granted in cinema, we become so grateful for the dialogue scene that an incredibly high level of attention is paid. By doing this, McQueen manages to imbue his conversation with the same level of gravitas and importance that he imbues the more elliptical first and third acts of the film. Additionally, while the conversation does fill in plenty of informational blanks regarding the film’s context, it doesn’t do so in a way that feels directly tied to what has come before; McQueen does not use the conversation as a way to string together what has been a disjointed narrative, nor does he use it to set up a more traditional narrative framework for what will come next. Instead, the scene seems to exist within its own context, as conversation moves from trivialities to a discussion of the IRA’s general position (which feels disconnected from the macro view of the situation we’ve seen in the first act) to debating the ethics of what Bobby is deciding to do. This conversation is bigger than everything that has come before; it doesn’t fill us in on this we had questions about. Instead, it raises its own questions about what we know is to come – Bobby’s impending hunger strike. And like the rest of the film’s economy, here 22 minutes is quite compact – a debate over the ethics of Sands’ choice could last a lifetime, and then some.

There’s an entire section of Hunger that might seem to refute much of what I’ve been saying. The film’s second act is a 22-minute conversation between Sands and a priest, which starts off as small talk and moves on to debating the ethics of the proposed hunger strike. It provides contextual information regarding the Troubles (“The IRA has backed itself into a corner,” the priest says at one point) and the reasoning behind Bobby’s decision (“I have my belief, and in all its simplicity that is the most powerful thing”). Yet this conversation, despite containing significant exposition and providing context to the film’s story, does not cheapen the power of the film in any way; quite the opposite, it may be one of the most moving and powerful conversations I’ve ever seen on film. Where does the scene’s power derive from? In addition to the obvious answer, which is that it’s incredibly well-written and well-acted, with the first 17 minutes knocked out in one take, it’s the contextual placement of the scene within the larger film. For the first 40 minutes or so of Hunger, we are watching a film that has barely any dialogue, and certainly no dialogue of real substance in relation to the film’s narrative. By the time we arrive at the scene between the priest and Sands, we have been retrained by McQueen’s formalism. There is plenty of room for fluctuation in the level of attention a typical audience member pays to a typical dialogue scene in a typical film – based on the interest level of that viewer, it could be anywhere from significant attentiveness to significant disinterest. One would be hard-pressed to find a viewer of Hunger who isn’t hanging on to every word of that conversation scene. After being deprived of dialogue for so long, we are hungry for it, and, becoming appreciative of something we once thought was to be taken for granted in cinema, we become so grateful for the dialogue scene that an incredibly high level of attention is paid. By doing this, McQueen manages to imbue his conversation with the same level of gravitas and importance that he imbues the more elliptical first and third acts of the film. Additionally, while the conversation does fill in plenty of informational blanks regarding the film’s context, it doesn’t do so in a way that feels directly tied to what has come before; McQueen does not use the conversation as a way to string together what has been a disjointed narrative, nor does he use it to set up a more traditional narrative framework for what will come next. Instead, the scene seems to exist within its own context, as conversation moves from trivialities to a discussion of the IRA’s general position (which feels disconnected from the macro view of the situation we’ve seen in the first act) to debating the ethics of what Bobby is deciding to do. This conversation is bigger than everything that has come before; it doesn’t fill us in on this we had questions about. Instead, it raises its own questions about what we know is to come – Bobby’s impending hunger strike. And like the rest of the film’s economy, here 22 minutes is quite compact – a debate over the ethics of Sands’ choice could last a lifetime, and then some.

So what formal avenues does Hunger free up for us? What new possibilities in the medium does it suggest? Hunger is, in the most general sense, a minimalist film, and minimalism – employed with every adverb from poetically (Carlos Reygadas) to passive-aggressively (Michael Haneke) – is the dominant mode of art cinema today. Yet few films being made, even by such master auteurs, have the supreme confidence in storytelling displayed by McQueen. The particular formalism being advocated here is believing in the strength of the moments of your film, and allowing those moments to speak for themselves, uncompromised by contrived scenes providing narrative context or seemingly necessary items such as character or narrative development. Trim the film down to its bare essentials, its strongest moments, McQueen seems to be saying, and the audience will take care of the rest. Hunger is as much an education in filmmaking as it is a work of filmmaking itself.

While it’s far too soon to tell what the lasting impact of Hunger will be, one senses that a push for this kind of de-contextualized storytelling is taking shape. Loren Cass, which was actually completed in 2006 but not released until 2009, contains a similar confidence of storytelling. Afterschool has a more traditional narrative structure, but the way that director Antonio Campos emphasizes specific details in scenes is not so dissimilar from McQueen’s take on the same. A movement consisting of this sort of de-contextualized, exposition-free, detail-based filmmaking would undoubtedly be challenging for audiences, but rare is the great work of art that doesn’t force its audience to elevate modes of comprehension.

Hunger is available in DVD and BluRay from Criterion Collection.

[AMAZONPRODUCT=B002YMWPUA]

[AMAZONPRODUCT=B002XUL6RG]