Back to selection

Back to selection

GRAVITATIONAL PULL: MIKE CAHILL’S “ANOTHER EARTH”

Originally published in the Summer 2011 issue. Another Earth is nominated for Breakthrough Director.

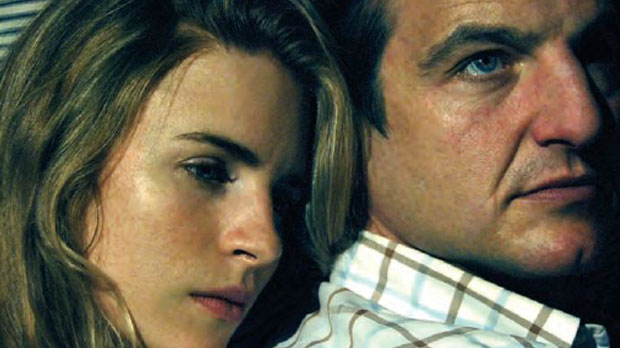

“It has a gentle sensibility,” says director Mike Cahill about his debut feature, the Sundance hit Another Earth. Indeed, this tale of grief, love and “Life Out There” does have a delicate touch, a sensitivity that sets it apart from the summer’s other science fiction. While in other films giant robots destroy entire cities — in 3D, no less — and romance is punctuated every 10 minutes by a train-destroying fireball, Another Earth, starring and co-written by newcomer Brit Marling, harkens back to the speculative parables of Ray Bradbury, Rod Serling and Harlan Ellison. In fact, describing the film’s human drama makes it sound like a small-scale indie picture and not modern science fiction at all. Another Earth begins with a horrible car accident in which a promising young high school student, Rhoda, plows into the vehicle of a prominent composer, John (William Mapother), killing his wife and child. Cut to several years later. Rhoda is released from prison and seeks out the composer to ask for forgiveness. But at the last second she chickens out, concealing her identity and accepting a job from the emotionally withdrawn man as a housecleaner. Of course, a relationship brews and with it conflict. Rhoda and John’s budding love shines light into both of their sad lives, but that light will be extinguished once the truth of her identity is inevitably revealed.

What makes this seemingly intimate relationship drama a science fiction summer release? Well because while all this is happening, another Earth has been discovered in our night sky. Suddenly appearing one day, it suggests that a rip in the space-time continuum has produced an exact duplicate of our planet — and that we might be both here and there. This simplest of concepts opens up new worlds of meaning for the film. Resisting the urge toward any kind of thriller plotting, Cahill and Marling keep their focus on their characters, and by doing so enable the film to effortlessly touch upon a number of psychological and even scientific themes. (The film’s “another earth” works as a metaphor for forgiveness and second chances, but it also is an example of what’s known in the quantum mechanics community as the multiverse theory.) Marling — tall, blonde and effortlessly empathetic — is riveting, while Cahill, who shot and edited in addition to directing, nails a haunting tone that is both melancholic and, finally, uplifting.

Cahill and Marling met at Georgetown University, where both were economics majors, albeit at different times. Cahill was working as a field producer for National Geographic when he returned to Georgetown for a film festival and met Marling. They moved to Los Angeles where Marling pursued acting and screenwriting while Cahill crewed, edited and did motion graphics work. They co-directed the 2004 documentary Boxers and Ballerinas, about Cuba and its Miami exiles, but Another Earth is their breakthrough. At Sundance, Fox Searchlight (which opens the film in July) paid in the low seven figures for domestic and international territories, but as you’ll read here, Cahill and Marling didn’t embark on the project thinking of mainstream success. In fact, if Another Earth hadn’t made our cover, it would have been a likely candidate for our Microbudget Conversation column over at our website

I spoke to Cahill and Marling at New York’s Crosby St. Hotel a few weeks before the film’s opening.

There’s a lot in the movie. There’s the psychology of grief, science and metaphysics, all wrapped up in the form of a science-fiction fable. How did all of these elements enter the project? What was the idea that you started with, and what layers were added later?

Cahill: I can give you a reference: Krzysztof Kieslowksi’s The Double Life of Veronique. A lot of people call this film science fiction, but I think it’s more suited to be called metaphysical. It answers this longing we have to escape the loneliness of the human perspective. No two ways around it: We see the world from our singular POV. No matter how many people we have around us, or how close we are with other people, we were born alone, we trudge through the world alone and we die alone. This notion of another earth — or another one of you, someone who can share in your history with you, who can feel you deeply — was really fascinating to us.

Marling: We were also really interested in this idea of, as you said, the psychology of grief. Or, what happens when you have a vision for your life, you are so set on a course, you really feel your life is going to be about something, and then [snaps fingers] you are radically thrust out of that? You can no longer be the person you thought you were. How do you come to terms with that? How do you accept the new person that you are? We were preoccupied with a lot of these ideas, but we did begin with the epic concept of, what if everybody here was also there? What if you could talk to yourself? What if you could not be so alienated and alone in your thoughts but could actually enter into a dialogue with yourself? And then we thought: Who would that mean the most to? And that’s how we found Rhoda, a girl so utterly alone in her grief, trying to come to terms with what she’s done. The possibility, or the wonder, of finding herself would put an end to that profound loneliness.

This idea of change, and other lives — I was reading The New York Times Magazine piece about you, Brit, and it talked about how you were on track after college to go into banking but you took a left turn into film and moved to Los Angeles. And it also said that you, Mike, had been doing video art, not narrative film. What inspired the change when it came to filmmaking?

Marling: Mike was making this sick, amazing video art on a site called Day Old Tea, which I think he’s since taken down. These videos were gems — poetic gems. They had this freedom to them, as well as this deep, emotional well of stuff. I was so inspired by them. We were looking at them one day and we thought, “Wait, what if we made a movie with this same freedom? And what if we married a narrative to it?”

Had either of you written screenplays before?

Marling: We had both been writing and reading screenwriting books, like Robert McKee’s Story.

Cahill: We went to the seminar.

How was that?

Marling: It was great!

Cahill: It was like the movie Adaptation. [laughs] He’s very smart.

My first job in film was as a script reader at New Line Cinema. I never took the McKee course, but the executives there did and they’d come back raving about it. I used to kind of look down on it, but then one day I read the book and thought it was pretty smart too. Later we’d sit around my production office looking at scripts and trying to figure out what his “negation of the negation” was.

Marling: I never really understood “the negation of the negation” thing. I think Mike got it.

Doesn’t McKee talk about movies where the drama is internal versus those where it’s rooted in the external? And that the internal stories are always the smaller films? Where would that put Another Earth?

Cahill: Another Earth twists all of that because everything external reflects the internal of [Rhoda’s] point of view. The aesthetic, the tone, the idea of this other earth moving closer as it’s getting more dramatic — all that is a reflection of her interior [state]. So it’s sort of inverted. You see in the beginning of the film that we have these bright, vibrant colors. She’s wearing a red dress that feels alive. And then there’s a tonal shift 10 minutes in that is completely in line with her journey.

Marling: I think you craft the mathematics of story first with your left brain, and then you go in with your right brain and find its flesh and blood and vessels and cells. We learned a lot about the structural part of [screenwriting] first. We spent weeks together being like, “How does this work?!” [laughs] And then we came up with the ending.

Cahill: We spent many months cracking the story and when it came together, it was like getting a Rubik’s Cube to connect.

Marling: We ran around Mike’s house screaming at the top of our lungs.

I had a completely different take on the ending the second time I saw it. Yours was the last movie I saw at Sundance this year, and perhaps I was simply too tired, but I discovered many other dimensions on second viewing.

Cahill: I don’t like to reveal too much about it, but there’s a very precise logic to the story and the ending. I like that there’s a little bit of ambiguity, though, because it leaves room for interpretation, which is always fun.

Brit, do you think of yourself as the actress when you write? Are you thinking of things you’d like to do on screen? Or things you know you can do well? Or are you just writing the character and then, on set, adapting to it?

Marling: One of the things that’s cool about writing and then acting is that [as an actress] you do a lot of your acting homework as you are writing. But there’s always more that you can mine — it’s just a question of how much time you have. If you have two months [to prepare for a part], you just dive as deep as you can and do it. Or you can work on a text for two years and still have so much more to give.

What about collaborating with Mike in the writing process?

Marling: As a director and as a human being, he has a deep sensitivity to authenticity. If something feels fake, it’s almost like Mike has a visceral reaction to it. We have a wonderful writing and director/actor collaboration that way.

Cahill: Brit was very committed in the writing process that Rhoda [exhibit] no self-pity. That was important and it made the character much more heroic — someone we can connect to and go along on the ride with. She doesn’t say, “Why me?” She moves through the story with bravery, without feeling sorry for herself, and with a desire to make things right. She gladly puts the burden on her shoulders and carries it without wallowing in self-pity. I think that’s one of the reasons this character is so strong. We want her to win by the end. We want her to be this protagonist who destroys the antagonism of guilt.

I find it interesting that after moving from the East Coast to Los Angeles to become filmmakers you moved back again to make the movie. I’m sure you could have spent a lot more time knocking on the studio doors, which is what many young filmmakers in L.A. feel they have to do.

Cahill: Coming at it from an angle is a necessity, you know? There’s the system and the system has walls. The doors are closed. And if [filmmaking] is something you are passionate about, and you want to do, you’ll figure out any way to do it. We went back to my mom’s house in Connecticut and found people outside the industry excited that we were making a movie there. Coming in as outsiders really gave us strength to follow through on the entire project.

Marling: The movie was really only possible because Mike is so unique as a director in that he does everything. He writes, directs, shoots, and edits, and it all happens in one fluid motion. He has this rounded complete artistic vision, and a tremendous skill set. As we shot things at Mike’s mom’s house, he would be putting [scenes] together, pairing them with music and showing them to me. And that [process] helped us find new things in the writing. As an actor you need to feel free in order to open up, and when the director can articulate a complete vision, you feel that freedom and can just surrender: “I’m safe. This person isn’t a faux-cocky confident young filmmaker — this person is genuinely confident in his art.” It’s a beautiful thing.

Cahill: It’s interesting to be a co-writer and director, editor and camera guy on the same movie because you can get really obsessive. I’ve seen the movie 500 to 600 times. And I could easily watch it again right now. I feel like every single edit is a success. I get really excited about it.

Tell me a little bit about the schedule on the production.

Cahill: There was an on-the-grid and off-the-grid schedule. We had this script and we started shooting without any production finances. We had a nice camera—

What did you shoot on?

Cahill: On the Sony EX3. Without prime lenses. We had a prime lens kit at our disposal, this $30,000 package, but we chose not to use it. It looked gorgeous, but it wasn’t the right aesthetic. It was too… something. I wanted it to look more unique, more lo-fi. So I disposed of the 35mm prime kit and we shot maybe eight days, trying to establish the tone, the aesthetic. It was playful and free, as Brit was saying. After those eight days, I met Hunter Gray, from Artists Public Domain, and then producing partners Paul Mezey and Tyler Brodie through a friend named [Nicholas] Shumaker. They said, “This film sounds incredible. We’d like to know more.” And I was like, “Well, actually I can show you what it’s going to look like.

And what did you show him?

Cahill: It was the final scene in the movie, actually.

Marling: That was an amazing day. We were in New Haven at Mike’s mom’s house. There was Mike; me; my younger sister, Morgan, who was a coordinator, did costumes and made shit happen; and our friend [Cai] Liang, who was Mike’s assistant director and gaffer and everything else. The four of us said, “We’re going to make a movie. We don’t know how. But here we are at Mike’s mom’s house, the food is free, she’s got a car and we’re going to make a movie.” [laughs] I woke up at 5:00 a.m. to go for a run and there was this low fog hanging over. It was thick, like out of another world. I wake up Mike, “Mike! Mike! There’s this thick fog outside. It’s so beautiful. Come look!” Mike comes out and says, “Let’s shoot the last scene of the film.” And I was like, “Mike, what are you talking about?”

Cahill: Have you seen Super 8? It was like, “Production value!”

Marling: I was like, “Mike, I can’t do that! I need to prepare!”

Cahill: And I said, “It’s going to cost $10,000 in fog machines later. Let’s take advantage of it.”

Marling: Mike was so smart. He said, “I’ll tell you what: Shoot this last scene with me and I promise you we’ll shoot it again. But do this with me now, for fun. And let’s just play and see what we get.” And this is what Mike is so good at: investing everybody with a sense of play. You can’t fuck up, because you’re just playing. It’s pretend, make-believe. There’s no way to make a mistake. So we go out, and Liang, who is five feet tall, stands on a chair with a green screen, holding up a piece a cloth—

Cahill: That we bought for $10. The cool thing about green screens is you can get a proper green screen or you can just go to the fabric store and buy a green cloth.

Did you wind up shooting the scene again?

Marling: We reshot it later in the fall when we had more of a budget.

Which version made it into the movie?

Marling: The one from that first shoot.

Did much else from those eight days make the final movie?

Cahill: A lot of it. All the stuff in the school, for example. My mom is a teacher, so we shot at her high school.

And this was all with a tiny crew?

Cahill: Just those four people. If we actually stopped and sat down and had a logical, realistic conversation, there’s no way we would have achieved the whole movie that way. But, that’s how you get started, get the ball rolling. Even if this is just an experiment in tone and visuals, that’s fine. But let’s at least make everyone in our small group believe that we’re making this film and hope that it will all work out. It was like a relentless pushing forward.

Marling: It was not waiting for somebody to say, “Oh you can do this.” The real trick is a shift in your mentality that says—

Cahill: Everything is permissible.

What were some of the experiments of those eight days?

Cahill: There were certain things we tried that didn’t work. We tried playing with the gravitational pull of the other world and that didn’t work so well.

Marling: We tied a bunch of flower petals to fishing line and hung them over the trees. This is what my sister, Morgan, came up with. The four of us were sitting in a parking lot on the ground with little weights from fishing lures, hanging individual petals all over the trees.

Cahill: The idea was that the blossoms were falling but getting pulled up by the gravitation pull, so they hovered.

Marling: I was standing around looking at all these petals attached to strings.

Cahill: Conceptually it was pretty cool. But when it played out, it was a little bit hokey. So it got axed.

So after this eight-day period—

Cahill: The producers got involved and they financed it. It was still micro-budget, but it was generous enough to hire a casting director and a crew.

Was it hard to adapt from your intimate off-the-grid approach to the on-the-grid one with a crew and producers?

Cahill: Well, we continued [the off-the-grid approach] all the way through. We did 15 days on the grid, 10 days off the grid, and 15 days on the grid. When we would go off the grid, it would just be us again.

Marling: I would still do my own hair and makeup. We would get costumes from the Goodwill. We’d be like, “Oh, we’re going to shoot a scene today,” and roll into the Goodwill and buy some things.

What were some of the off-the-grid moments from later in the shoot?

Cahill: When [Brit] walks down the pier and there’s this massive other earth, that was off-the-grid because we didn’t need sound or major production support.

Brit, earlier you touched on the issue of authenticity. I was going to ask you both how you had the confidence to tell a story in which large parts are outside the world of pure realism. You had to take a leap of faith that elements of the script, like the contest, for example, wouldn’t come off as hokey, as you say.

Cahill: Well I gave you the example of the floating blossoms. I am very aware of things like that as we are moving through the story. At times you feel like a magician trying to do sleight-of-hand, showing one thing over here [he motions on the table] so the audience isn’t looking over there. One thing I hope is that the audience allows certain things to wash over them, that they realize that this whole construct is for metaphor. This whole [story] is built around trying to achieve a transference of emotion. It has a gentle sensibility. There is nothing didactic going on. It’s just about something that connects us. There are some places where it could have gone a little hokey, but we axed them.

It seems like you made an effort to give everything the same sort of emotional tone. So, for example, instead of having the newscast feel like a regular newscast with peppy music, graphics buzzing around and upbeat anchors, you inflect it with a similar vibe as the rest of the movie. Even the scientist’s voiceover has a wistful, somewhat melancholic tone to it.

Marling: I think it all feels a bit like a fable. And because of that, maybe you’re willing to suspend your disbelief a bit more.

Tell me a little bit about your post-production schedule.

Cahill: In post-production, we had quite a lot of footage.

What did you cut on?

Cahill: Final Cut Pro. I did an assembly edit that was 2 hours and 40 minutes and I think we edited for eight months. Those weren’t 10-hour days of cutting. Sometimes it would be like two hours, or one hour, or six hours. We had the time to let it breathe. We would do screenings with the producers and then they’d write down notes and I’d take them and incorporate them. It was a safe place for everybody to offer their critique. We picture-locked in the summer and then had four or five months to work on the score, which was really exciting. We worked with these guys, Fall On Your Sword. Somehow they combined this cool, pulsating momentum-moving electronica with warm, organic, real sounds and textures. [The score] is kind of like the “science meets the humans” story. It was the perfect sound for the movie.

The first time I watched the movie, it felt like, as you say Brit, a fable. I viewed the whole “another Earth” concept as both metaphor and riddle. The second time, however, I realized that there is science involved too. Did you think about things like quantum physics as you were making the movie?

Marling: Right after Sundance somebody sent us a review in The New York Times of a book by Brian Greene, The Hidden Reality. He writes about multiverse theory, which is this theory that if there is an infinite number of particles in the universe, and the universe is infinite, then it’s like a deck of cards: if you shuffle the deck of cards an infinite number of times, you’re bound to repeat the same particle order. So then it’s logical, and maybe even mathematically reasonable, that you would repeat the same particles of this earth somewhere. So you literally would have duplicate universes, duplicate Earths, duplicate us.

Cahill: We were on a panel with Brian Greene recently and the moderator said, “Wow, he’s been doing this science for years, and you guys just sort of came up with it!”

Marling: But I think there is something to the idea of people arriving at similar feelings, whether it’s through art, through science or through psychology. Whatever tool you’re using to get at it doesn’t really matter. People do arrive at ideas at the same time. We came from a complete fiction, narrative, storytelling perspective, and Brian came from deep physics, but we arrived at the same feeling, which is the desire to know yourself more deeply, to connect somehow through a duplicate you.