Back to selection

Back to selection

HOSSEIN KESHAVARZ, “DOG SWEAT”

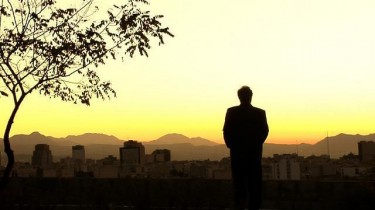

Earnest and terse, Dog Sweat is a movie that feels like it was made by the skin of its teeth, pulled together through sheer force of will; what’s at stake for the filmmaker becomes an indelible part of the experience for the audience in a way few films accomplish. A sprawling drama with multiple protagonists, tracks several young Iranian adults who in their own quiet, and in some cases not so quiet ways, are running up against the rampant oppression of an authoritarian theocracy and a older generation grown stale with compromise, who have grown complacent about lowered expectations for freedom and dignity. The director, Hossein Keshavarz, making his directorial debut, grasps on to one unforgettable tale after another: a young woman yearns to be a singer, while another engages in an affair with a married man as her home life teems with barely veiled misogyny. A pair of young couples, one straight and one not, attempt to find a space in Iranian society in which to share their love, while a hard living young man receives a difficult education in the power of the state when it harshly visits his own family.

Shot verite style in the streets of Tehran just before 2009’s rigged Iranian election, Dog Sweat deftly intercuts these stories, building on to a sharp indictment of Iranian political repression, one that seems to have denied the humanity and aspirations of its children. That this fact is as evident in the film’s aesthetics and narrative as it is in its very making is a solemn fact; Keshavarz made Dog Sweat illegally knowing he could never get his movie approved under Iran’s strict censorship code, just like Bahman Ghobadi had to for his stirring 2010 drama No One Knows About Persian Cats. They both, along with Hossein’s sister Maryam Keshavarz, the director of the Sundance favorite Circumstance, are part of a new generation of Iranian filmmakers who are undeterred by the very real dangers of depicting the disappointments and desires of the Persian masses.

Dog Sweat opened in New York last weekend. It opens at Los Angeles’ Laemmle Music Hall on Friday.

Filmmaker: At one point in your formative years as a filmmaker did you decide to make this type of Altmanesque, multi-strand indictment of the the repressive nature of Iranian society? You were raised mostly in the United States I believe, so I imagine your experiences going back to Iran had a significant impact on you?

Keshavarz: We shot before the Green Revolution. It’s kind of a roundabout story, a long story about how we got to it. What happened is, I was in Iran and had spent more than three years there, before and during the filming. I was actually getting ready to shoot another film. One I had been working on since film school. It was going to be shot in Iran and it was going to have all the proper permits and a famous Iranian actor and so when we were geared up for that we went to the Berlinale script clinic.

So what happened was, my Mom was in Iran and she was really badly hurt in an accident, someone hit her from behind. So we brought her to the nearest hospital, which was a public hospital but now has just been run down after the Islamic Revolution. She was in critical condition, she broke her neck and foot and shoulder, it was horrible. I spent a lot of time in this hospital and I really started looking at it. There would only be one bathroom for an entire wing. They had bathrooms for each room, but they just weren’t cleaning them. It was terrible, all these sick people would have to go to the bathroom and couldn’t. What was interesting was that later, at the beginning of Ahmadinejad’s term, he was obviously terrorizing people and many of them were being taken from this hospital for their political leanings. So when we would come back we would see all these people who had gotten beaten up and who were being treated. I remember talking to some of them. The producer was with me, she’s a very very brave and smart woman, her name is Maryam Azadi, she was the one who really started talking to everyone and seeing what was happening. I remember, half of our family is very liberal and half of our family is very conservative, so one of the people in my family, my uncle, I said to him, “now you can’t say that this isn’t something that happens,” and he would say, “those people are just trying to cause trouble.” If someone doesn’t want to hear the truth, they won’t.

So I spent a long time with my Mom in Iran then I helped her get back to the US and took care of here when she got here, so it was a little while before I came back again. When I came back I think things had changed. Life had really changed. Iran had changed. It was a different political climate. I had a project I loved very much, but I wanted to make something more immediate. So I just had to write this script. I wrote the first draft in about seven days. Then I worked with Maryam on it. I grew up in the US, she grew up in Iran and had gone to film school in Iran and had lived in places I had no idea of. So the first draft just kinda came out of me and then I talked to her and some other people and I didn’t think that we could make it because it would have to be done underground and you’d have to be crazy, but I just wanted to write what I felt and what I saw. That was the basis for this film.

I’ve always loved Altman. I’ve always loved those sort of films. The reason why this project took on that shape is because once we decided we weren’t going to go to the censorship board, than all these related stories opened up to us. A lot of these stories just happen to be things you see everyday, very amazing things that happen, yet because of all of the censorship, they’re never seen, or shown, and so I really wanted to make a portrait of this young generation that’s fighting to be free. That’s why we told the multiple stories, to tell the story not just of one person, but of a whole society.

Filmmaker: You tend especially on how the middle class in Iran, who are often cosmopolitan and educated, passively deals with the oppression by the theocracy and finds ways to thrive despite it all.

Keshavarz: All the limitations are there and real for people, but they are going to live their lives no matter what. In the beginning scene, the guys are drinking whiskey and that’s illegal, but they’re kind of just laughing about it. Nobody really thinks about it the way you would think, from a Western’s perspective, they would think about. I always think the people in films from the US about people living in Totalitarian societies always don’t get it. People are people. Of course they don’t like the repressions but they’re focused on falling in love or getting to their job or being with their friends. I think in general, images we have of Iran in the US are very skewed. In the Western media it’s like, “Iran, a nation of fundamentalists!” Iran is actually a very vibrant country. In Iranian film, there is censorship. There’s no boyfriend and girlfriend in Iranian films, yet everyone who is young has had a boyfriend or girlfriend. The great Iranian films have had to be very stylized films, a Kiarostami film that takes place in a rural village or Children of Heaven where it gravitates around these children in order to get around the censorship. The thing is, Iran is mostly urban and the truth is most people are around twenty-five years old and they’re very well educated, middle class young people living in a city of 20 million people, which always makes New York feel like a breeze. We wanted to make something that reflected our lives and the prevailing mentality.

One of the reasons the name of the film is Dog Sweat, and Dog Sweat by the way is prohibited since that’s slang for moonshine, is that its prohibited and yet its very mundane. Even though its prohibited, that’s what they want. They just want to have a good time. A guy and a girl, even though that’s prohibited technically, they want to have a place where they can go home together. So of this I can now talk about a bit more freely, the whole notion of why it’s called Dog Sweat, but when I wrote it, it was a different feeling. The feeling was to represent all these people who happen to come up with all this pressure from society and they have to decided to conform or live the way they want.

Filmmaker: Did you have troubled finding and keeping collaborators because you were shooting illegally?

Keshavarz: Yeah, that was definitely a very difficult thing, because everyone lives there. We shot the film before the elections. I don’t think we could shoot the film now. They’ve become much more sensitive to this kind of stuff. I kind of think the film speaks for itself. I don’t usually try to get involved with the political conversation. I try not to get tangled in these issues for the sake of the actors. The film is about life and life is politics, which is as it should be, but its also about these human beings looking for connections and love. I think that’s a more powerful thing than someone lecturing to you. We’ve been really careful in that we haven’t gone on opposition television stations and we’ve kind of shied away from any sort of politics so that people could focus on film as film.

Filmmaker: But did you have trouble working with people you wanted to because they were afraid of the restrictions?

Keshavarz: The whole thing was very difficult. Its not the typical film where you can shoot what you wrote and have thirty production days in a row. We just shot what we could get, we shot bits and pieces. A lot of times, we would have a great scene, but we could only shoot the middle of it, because things would blow up or it was just too risky. So we had to be very agile and take what we could get and try to always remember what the story we wanted to tell was and how we wanted to tell it. The film we wound up with is vastly different from the script. Which is fine. That’s the kind of thing you sign up for when you do a film this way. You have to be open to the world around you. There are a lot of good things also. The thing is, you really just have to put the blinders on and go forward. If you’re dedicated to it and others are dedicated to it, you can work through those issues.

Filmmaker: Did shooting and constructing the film that way make it difficult to edit?

Keshavarz: The editing was so difficult. It’s difficult to cut these sort of multi-character stories to begin with. Though we shot before the election, in some ways its predictive of what happened in a way. There’s a whole generation of people who are sort of fed up with what’s going on. They just don’t want to pay attention anymore and they just want to have fun and then you saw what happened with the elections where everyone was like, “well this is too much,” and then they all suddenly protested and I don’t think the authorities were expecting that. One of our stories is very similar, where we have a character who is a slacker, he doesn’t give a shit, until he has an awakening. We had another story that was quite political, and then we actually took it out in the editing mainly because we just thought it would cause problems. We did this film in order to have our say in the way we wanted to say it, but its always a fine line because we’re in this crazy world right now where we have to be cautious. Its always been a fine line for us.