Back to selection

Back to selection

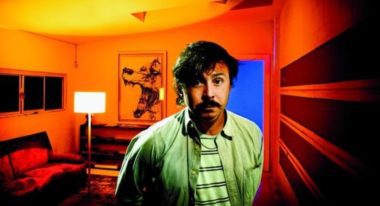

Gerardo Naranjo, Miss Bala

A model hybrid of seemingly effortless form and true-to-life action is the astonishing Miss Bala, by 42-year-old Mexican director Gerardo Naranjo. His earlier, teen-focused works, Drama/Mex and I’m Gonna Explode, while they are expertly crafted (and especially alluring for those with a penchant for handheld camera and super-8), were a tad heavy-fisted for the subject matter, as if they were laden with an extra injection of testosterone. Could it be that in making Miss Bala (bala means bullet, and is a pun on Baja) about grown-ups and placing a 23-year-old woman (and her POV) front and center, he has, in the best way, both softened and retooled his creative hand?

The play of light and dark pushed beyond the usual boundaries, frequent panning and reframing that respect characters and their dilemmas, and long, sometimes baroque takes testify to his growth as a filmmaker with a more subtle yet ultimately stronger aesthetic. Hungarian cinematographer Matyas Elderly, who worked in his home country with the smooth, unhurried Kornel Mundruczo (Delta, Tender Son), aided in the transformation.

Naranjo has a strong feel for architecture, his characters dramatically shot against structures and interior detailing. He knows how to move them efficiently and dramatically through the spaces in between, whether inside a huge auditorium (a marvelous scene full of confetti and mariachi music, when the protagonist wins the Miss Baja California title), a claustrophobic bedroom, the patio of a grand hotel, or the inside of a car. At the same time, he captures the the right, and generally most striking, angles of her elongated ex-model’s torso and face with planes worthy of Picasso.

At the drama’s center is Laura (Stephanie Sigman), a reserved, poor, but naturally glam 23-year-old who lives outside Tijuana, functioning as mother for her father and beloved younger brother in their shack of a home. She hopes that winning the pageant will help her earn money. Her noble goal is to pay for the kid’s education.

In a chi-chi nightclub where her pushy best friend and fellow contestant takes her to meet important people, she becomes the only witness to a massacre of police and American DEA employees by members of the notorious drug cartel, the Star Gang. (She hides in the ladies’ room.) Its nondescript leader, Lino (Noe Hernandez), sees and takes a shine to her, but also realizes she can serve a practical purpose: Her innocence and calm countenance make her ideal for delivering drug and money transfers between Mexico and the U.S. In the meantime, Lino makes sexual overtures she is in no position to reject.

Naranjo neatly outlines the marked contrast between the meretricious competition and the dealers’ vulgarity and lack of couth, although they sometimes overlap. Beginning immediately after her televised crowning, which the cartel bought for her, Laura becomes increasingly defiled, dehumanized, forced to participate in some nasty criminal transactions, and reduced to a sex toy—mostly for cartel members but also for one of the highest ranking generals, an old letch, in an omnipotent government that exhibits little room for dissent. Her cheap tiara might as well be a crown of thorns.

Laura is a microcosm of the disintegrating northern Mexican social order. (Some of the most egregious killing and torture take place on a romantic sandy beach alongside the gorgeous ocean for which Baja is a famed tourist destination.) Shootouts, magnificently choreographed, occur without high-gloss Hollywood backdrops or F/X, but instead crassly, on charmless city streets or next to soulless motorways in Tijuana—in other words, as in life.

Alliances between cops and criminals, and between gang members, shift with regularity; betrayal is the norm. The ambiguity of Laura as both clever survivor and half-willing mule (mostly out of fear, but an element of the Stockholm Syndrome plays a part) becomes more sharply defined, not so much by her (even when she helps the state, she is framed for crimes she did not commit), but by bureaucrats and military men in power. They determine her fate—which ends up gray rather than black or white in an inspired climax, an unexplained finale for which Naranjo trusts the viewer to try to piece together.

Recently the affable filmmaker, a committed film buff, and his costume-designer girlfriend relocated to Brooklyn for an unspecified period of time. Certainly at this moment he is much more interested in getting his next film made in Mexico (where he was recently scouting, even weathered a storm, on an oil rig) than in conquering Hollywood.

Of course, nothing is carved in stone. If Miss Bala, Mexico’s official nominee, wins the Academy Award for best foreign-language film, he could start working both worlds right away like his peers and countrymen Inarritu, Cuaron, and del Toro. The choice of Manhattan over Los Angeles could be an indicator of his priorities and goals, especially since he is an AFI graduate. Personally, I have a hard time imagining him under the thumb of the suits.

Filmmaker: Your first two features that I saw were about teenagers. Here the story is not about a teen, but about a slightly older woman. The point of view is totally different.

Naranjo: The movie was very different. The subject was very different. But I don’t think it is a completely different entity from the youngsters I directed before. I got close in the same way, just trying to communicate the feelings of this person. The most important difference is that I took more time explaining what she was feeling than in the other movies, where I was watching everything all the time just to get to the next scene. I think one of the lessons I learned in the movie was that I had to take a little more time to explain some emotions. So I think it was a little slower.

Filmmaker: Do you think that may have affected the form?

Naranjo: No. The other characters were more conscious of themselves. I think this actress, just because of where she was from and her circumstances affected her in that she was a little more naïve or more unconscious of it, but I didn’t approach it all that differently.

Filmmaker: You make all your films in provincial cities in Mexico, not Mexico City: Tijuana, Guanajuato, Acapulco.

Naranjo: That is a very conscious thing. I do believe that if Martians would ever come to earth after we’re done with the planet, they will think that almost everybody in the world lived in New York or Mexico City. I think that’s a fault of cinema. We think that great cities have the best stories, but I don’t think so. Cinema is a way to know the world. Every time I see a film shot in Mexico City, I think it’s so dumb to look at that incredible background we have, like everybody’s shooting the same street. So it’s an opportunity to cover a new world every time.

Filmmaker: This idea of a beauty contest and the drug cartel coexisting, was that your initial conception of the film?

Naranjo: No, no. At the beginning we just wanted to talk about violence. That was the subject. So we were developing different storylines. In fact, in the main story there was a DEA agent from the US: the contrasts, the black and white, the conception of good and bad that American culture has. So a DEA agent goes to Mexico and finds that the line between good and evil is much more blurred. That was the story. We were about to shoot it.

Then an article appeared in the newspaper about a beauty queen arrested with criminals. We wanted to find an explanation, how a person with a stupid role like a beauty queen can be arrested with the persons with the worst jobs on earth, these criminals. How can this happen? I don’t think in many countries it could happen. But I think it explains a lot about how Mexico works, how power has to do with fame and how much power has to do with corruption.

Filmmaker: I think it also makes her degradation stronger without completely knocking you over the head with it.

Naranjo: I think that it’s a guilty pleasure for everybody to attack this kind of woman. I think that people watching the movie get off, on an unconscious level, by seeing a beauty queen terrorized. People want them to suffer. Finally they are getting the chance. The most important thing was that we didn’t want to get much into the society of the criminals. We were not interested in that. Normally the movies in Mexico dealing with this are about the poor guy who doesn’t have money for medicine, and then he commits a crime to cure his son of leukemia.

Filmmaker: Lino, her chief cartel contact and involuntary lover, is like a two-dimensional prop for her. But she is ambiguous. How much is she consciously involved in the criminal activity, and how much is she just trying to survive?

Naranjo: I tried to develop some complexity. Normally the complexity of the characters has to do a lot with sabotage, when they are sabotaging themselves. Here I wanted the complexity just to come out of the frustration of why she doesn’t run, why doesn’t she do anything. Also that is a metaphor for what I think people are going through, because with the violence in Mexico everybody is frozen, in a very stupid way.

So when people are frustrated, they say, “Oh, your actress is so passive that she doesn’t do anything.” I don’t think that people in Mexico have the duty or obligation to react violently. We don’t have a military education. We don’t know how to respond to violence. The power of a society to fight against crime requires organization. It requires the coming together of society. I think we are not doing that.

Filmmaker: How was your collaboration with d.p. Matyas Elderly, from Hungary?

Naranjo: I contacted him and told him I was very fond of his work with long sequences and a fluid camera. I invited him to Mexico. It was a big problem when he came, because I already had a script. He has a great sense of storytelling. He gave me a great lesson about confidence and trusting the audience. We went through the script and the way I wanted to shoot the film, and he was like, “People already know that.” In the big shooting scene I had 10 people dead on the ground. He said, “You are giving too much; take less, less, less.” He was always challenging the amount of information we were giving people. That was for me one of the great collaborations.

We decided that for the visual style, nothing would be handheld, everything would be done in a dolly more or less. He knows camera people from the era of Miklos Jancso and from the Bela Tarr time. So there is a lot of wisdom, like how to make the dolly not make noise, how to make the dolly look balanced, how to approach the lack of space. There are certain things that a dolly can do when it doesn’t move, and I didn’t know how to do them. He’s a nutcase, but also into a lot of soft discussion.

Filmmaker: What was your strategy for filming the shoot-‘em-up scenes, the super-violent ones that we are not accustomed to?

Naranjo: We thought about it all the time in terms of contradictions. Not doing what is normally done. The shot in an action scene is known for the ejaculatory part of the weapon, just throwing things out. We decided, let’s turn the camera around and see the pathetic effect, not the glorious effect of the destruction. We’re not cutting. In most thrillers we know the intentions of the bad guys, and this keeps the audience frustrated. Everything in the movie is working contrary to what is normal.

Filmmaker: But it feels so real. There’s nothing embellished about those action scenes.

Naranjo: A lot of the information that comes to the viewer comes through the audio. The masters I really respect, I will never think I’m close to what they do, but I think the great masters, what they can do, is to make you imagine what you don’t see. Fragmenting and withholding information offer you much more than if you see the posing. We tried certain of those techniques. When you say it’s real, all the dialogue was spoken by criminals and humble people. The dialogue you don’t see onscreen, military comments, I think you can see that these people have no sense of the moral implications of their actions. They don’t give a fuck about it anyway.

Filmmaker: Who are the masters?

Naranjo: The good ones like Ozu, the use of offscreen action that gets into your soul, or Dreyer. You’re imagining everything all the time. The use of empty space is very important.

Filmmaker: Can you think of an action director who does that?

Naranjo: That’s a good one. Kaurismaki has used it in a strange different way, like using the violin in a very subliminal manner. That’s a good question, an off-screen action director!

Filmmaker: There is a lot of treachery in the film. Nobody is who you think they are.

Naranjo: What the movie communicates well is that feeling. You say “films of confusion.” But I think what happened in Mexico is much much worse. People are dismembered, their heads have been cut off, all the rituals that criminals do with the dead body–the religious cult La Santa Muerta. The Italian Mafia had a bit of that, with the canary and cutting certain fingers.

But in Mexico the level of cruelty and playfulness are much more. People are dismembered, their heads have been cut off, all the rituals that accompany death are present. I think playing with the dead body has something to do with ancient Aztec traditions. Cutting the fingers and putting them inside all the orifices of the body: Where did that come from? What is the meaning? What is the reason? The guy is dead already. Obviously it’s a message to the living ones.

Filmmaker: What about your recent move to New York? What are your plans?

Naranjo: I have a plan to shoot a movie in Mexico, I hope soon. I think to make a US film I’d need spend more time here. I know I’m a foreigner. I’m proud of my accent. I would love to make a movie in America. I would love to work with American actors. James Russo was a delightful experience in Miss Bala. I’m not in a rush.

Filmmaker: Moving here is not about your personal life?

Naranjo: I think I’ve been struggling a lot to do my work. I’m very interested in learning and studying more. The reason to be in New York is to see more movies. I don’t think a filmmaker or artist should stop learning. I’m not that kind of filmmaker. I don’t feel like I should be doing a movie here yet.